Exactly 20 years ago, on January 22, 2005, in Palm Beach, Florida, Slovenian model Melania Knauss married businessman Donald J. Trump, wearing a dress that weighed 66 pounds

A Thread 🧵 of small curiosities

And Happy Anniversary to the Presidential Couple! 🎉

A Thread 🧵 of small curiosities

And Happy Anniversary to the Presidential Couple! 🎉

Legend has it that the dress weighed about 66 pounds, thanks to its extravagant and baroque design, created for her by John Galliano, who was then the creative director of Dior

It’s even said that she had to sit on a specially designed bench during the ceremony

It’s even said that she had to sit on a specially designed bench during the ceremony

At the time, there was no apparent feud between Vogue and the First Lady, so she was given a dedicated cover and feature for her wedding!

It’s even said that she was accompanied to Paris for the fashion shows to select her dress

It’s even said that she was accompanied to Paris for the fashion shows to select her dress

The proposal from the magnate to the stunning model took place at the 2004 Met Gala in New York, where Melania dazzled in an elegant black, web-like, outfit

With a $2 million ring, the tycoon bound to himself the woman who would go on to become the two-time First Lady of the United States 🇺🇸

The collection that captivated Melania was John Galliano’s for Dior, inspired by the famous Empress Sisi, the iconic Austro-Hungarian empress 🎀

To create the dress, 1,000 hours of work were required, with 500 hours dedicated to embroidery, and 1,550 crystals and pearls

The dress used 295 feet of satin, with a 13-foot train and a 16-foot veil

The dress used 295 feet of satin, with a 13-foot train and a 16-foot veil

The exact cost of this dream dress is unknown, but some say it was around $100,000, paid by the magnate, who was already on his third marriage at the time, to fulfill his young bride’s dream

Following the well-known bridal tradition:

The dress was her “something new”

“Something blue” was her lingerie by La Perla

“Something borrowed” was the stunning necklace by Fred Leighton

The dress was her “something new”

“Something blue” was her lingerie by La Perla

“Something borrowed” was the stunning necklace by Fred Leighton

And “something old”?

Here comes Melania with her signature touch of genius: a vintage family rosary intertwined with flowers, replacing the traditional bouquet

Here comes Melania with her signature touch of genius: a vintage family rosary intertwined with flowers, replacing the traditional bouquet

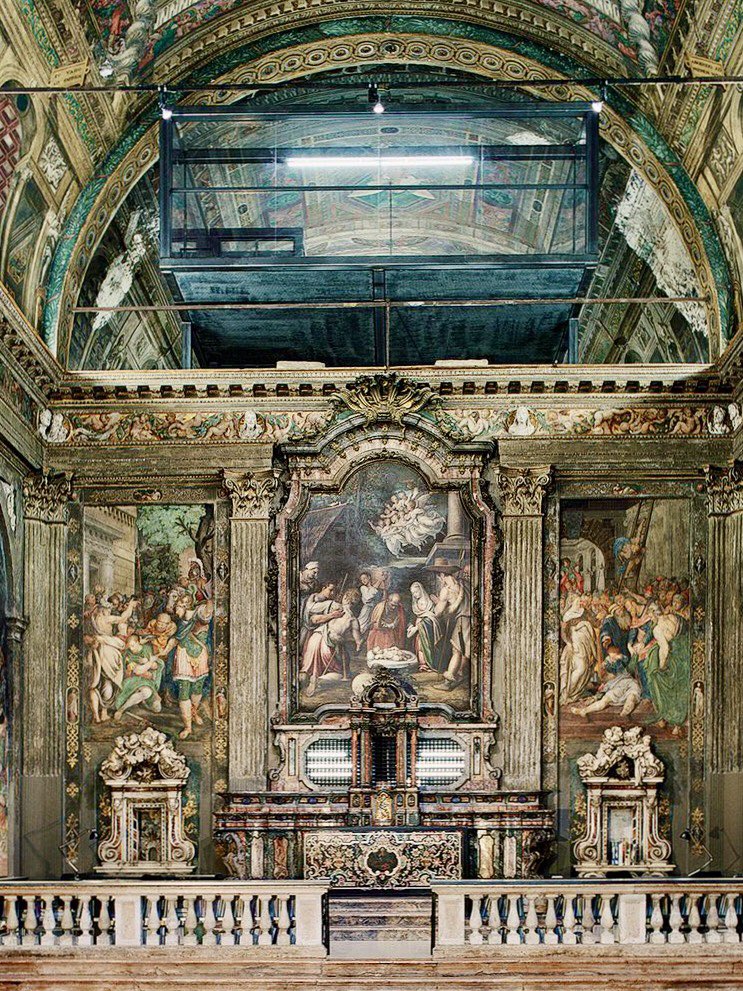

No bouquet toss, then, in the stunning setting of Mar-a-Lago—a bit different from how we see it today, but still as magnificent as ever

Breaking with tradition—neither keeping the dress a surprise nor carrying a traditional bouquet—has certainly brought Melania good fortune ✨

She has now reached 20 years of marriage despite challenges, busy schedules, and the joy of welcoming their wonderful son, Barron

She has now reached 20 years of marriage despite challenges, busy schedules, and the joy of welcoming their wonderful son, Barron

Photos of Donald and Melania’s lavish wedding reception aren’t too common online

Rumor has it that most of the guests were from Trump’s side

One exception seems to have been a striking woman, rumored to be Ines Knauss, Melania’s sister—but not much is known about her…

Rumor has it that most of the guests were from Trump’s side

One exception seems to have been a striking woman, rumored to be Ines Knauss, Melania’s sister—but not much is known about her…

That said, Happy 20th wedding anniversary to POTUS and FLOTUS, and Best Wishes for the next four years, during which all eyes around the world will undoubtedly be on them 🎉

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh