I said the CIA, FBI, and DoE haven't shared why they think covid is a lab leak.

We can infer they don't have much evidence, because they can't even agree on which lab it leaked from:

But there is actually one article with details about the FBI's logic.

We can infer they don't have much evidence, because they can't even agree on which lab it leaked from:

But there is actually one article with details about the FBI's logic.

https://x.com/tgof137/status/1883941046486487448

This WSJ article interviews former FBI scientist Jason Bannan and talks through some of his reasoning.

archive.is/eESVG

archive.is/eESVG

It honestly reads a lot like the same kind of debates you see on Twitter.

Some FBI scientists thought it was weird that the closest bat viruses are found in Yunnan, far away from Hubei.

Some FBI scientists thought it was weird that the closest bat viruses are found in Yunnan, far away from Hubei.

Maybe that is weird, but it's also the same thing that happened with SARS1 in 2003. The closest ancestors to SARS were found in Yunnan, but the virus was found at markets in Guangdong and Hubei provinces.

These viruses can only spread well in places where there's a high density of humans, so an outbreak is more likely to start in a market in a big city, and less likely to happen on a rural farm.

Also, if a few people get sick on a farm, no one is going to detect those cases.

Also, if a few people get sick on a farm, no one is going to detect those cases.

So these viruses are going to show up at a market in some big city, in southern or central China. (they eat less wildlife the north + regulations are better in some cities)

Guangzhou is probably a more likely place for a spillover than Wuhan, but neither are unreasonable places.

Guangzhou is probably a more likely place for a spillover than Wuhan, but neither are unreasonable places.

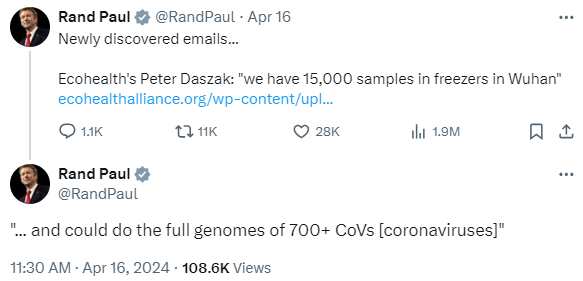

The article also had some more detailed discussion about genetics, apparently lead by 3 scientists at the Defense Intelligence Agency, who influenced Bannan and his colleagues at the FBI.

The paper written by those 3 scientists has been made public:

It offers a theory for how SARS-CoV-2 was made. docs.house.gov/meetings/VC/VC…

It offers a theory for how SARS-CoV-2 was made. docs.house.gov/meetings/VC/VC…

That's a theory that was sometimes used in 2020, Yuri Deigin also proposed it in his famous medium article:

What's a receptor binding domain? Why would scientists combine a bat virus and a pangolin virus?

It's all a little bit complicated.

It's all a little bit complicated.

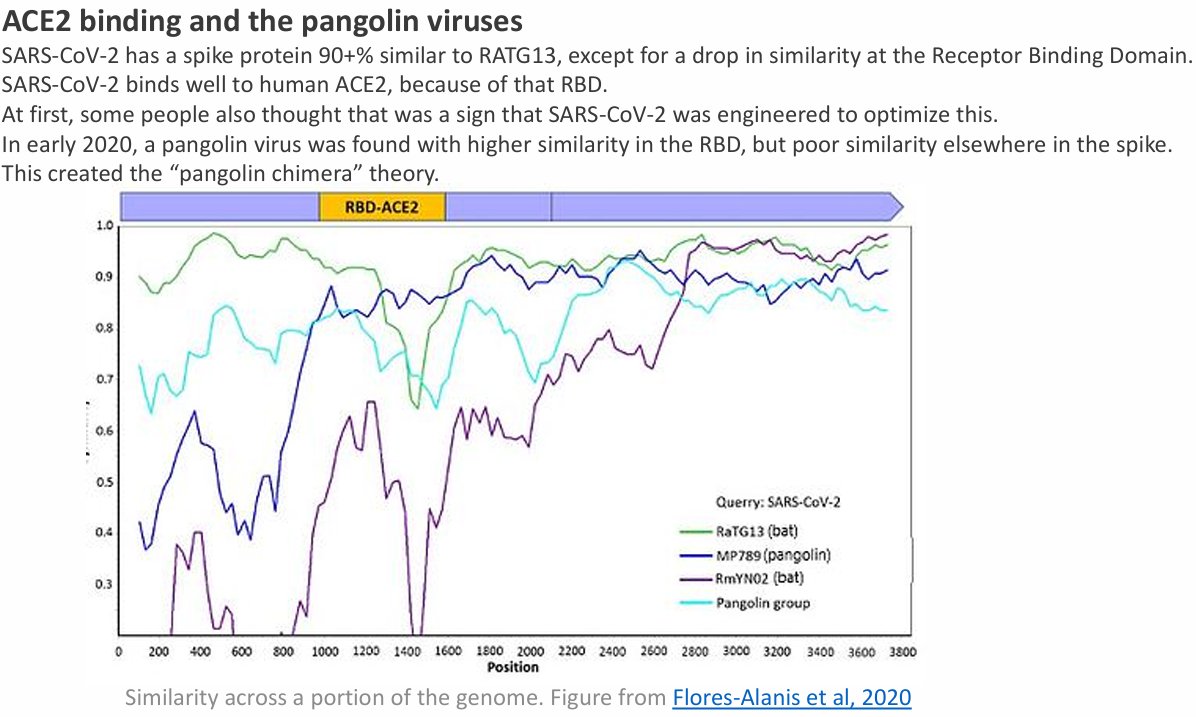

Early in 2020, we noticed that SARS-CoV-2 binds well to the ACE2 receptor in human cells, just like the 2003 SARS virus did.

But SARS2 binds in a different way than SARS1 did.

It looks like SARS2 is actually less efficient at binding than SARS1 is.

But SARS2 binds in a different way than SARS1 did.

It looks like SARS2 is actually less efficient at binding than SARS1 is.

Kristian Andersen wrote a complicated argument about why no one would likely engineer this particular method of binding. It's not what any computer model would predict. So he said it must have come from natural selection.

The next thing we discovered in 2020 were pangolin viruses that also bind to human ACE2, and they do so in about the same way that SARS2 does.

So that also suggested that this feature of the virus came from nature.

So that also suggested that this feature of the virus came from nature.

Somewhere along the way, the WIV disclosed a virus called RATG-13, that's 96% similar to SARS2.

It happens to be much less similar in the one place, the receptor binding domain, which effects how the virus binds to ACE2.

But these pangolin viruses were closer in that spot.

It happens to be much less similar in the one place, the receptor binding domain, which effects how the virus binds to ACE2.

But these pangolin viruses were closer in that spot.

So, some people theorized that maybe scientists could have combined a bat virus and a pangolin virus to make SARS-CoV-2.

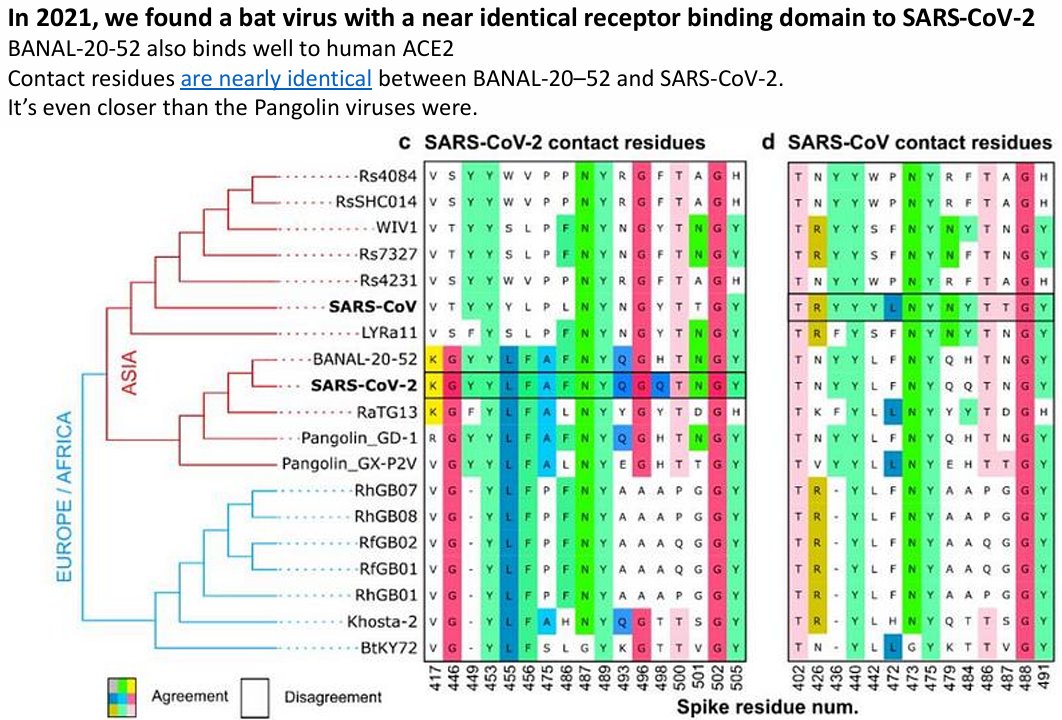

That might have sounded good at the time, but that theory died in 2021, because other scientists went out looking in more caves and discovered bat viruses that have the same receptor binding domain as SARS2.

Those viruses (like BANAL-52) have a receptor binding domain that's even closer than the pangolin viruses.

That makes it very clear that this feature originated in nature, and pangolins aren't necessary.

So, if that's the FBI's theory, their theory has been wrong since 2021!

That makes it very clear that this feature originated in nature, and pangolins aren't necessary.

So, if that's the FBI's theory, their theory has been wrong since 2021!

That doesn't necessarily mean that the lab leak theory is wrong.

Lab leak theorists saw these same viruses in 2021 and decided these were great evidence.

They thought these made the lab leak theory even stronger!

Lab leak theorists saw these same viruses in 2021 and decided these were great evidence.

They thought these made the lab leak theory even stronger!

The new lab leak theory is that maybe a lab found one of these other viruses before 2020 and did some gain of function research on it.

And, of course, that's hard to disprove, with absolute confidence.

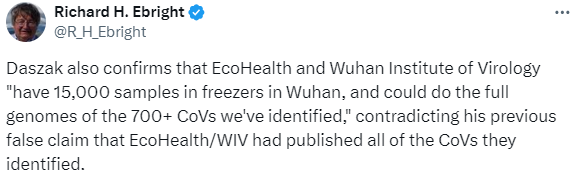

We have pretty good evidence that the WIV did not have such a virus, because they published their collection of related viruses in the middle of 2019.

We have pretty good evidence that the WIV did not have such a virus, because they published their collection of related viruses in the middle of 2019.

https://x.com/tgof137/status/1783256175401992414

And the intelligence reports actually say they have no proof that the lab had such a virus:

https://x.com/tgof137/status/1783256186827247864

But you can always make up some story about secret viruses, unpublished viruses, secret research programs, or whatever.

And in the end it just becomes an argument about probability. What are the odds they found that secret virus and did this specific work on it?

And in the end it just becomes an argument about probability. What are the odds they found that secret virus and did this specific work on it?

I tend to think the way the lab leak theory keeps mutating is, in itself, evidence that this is all unlikely.

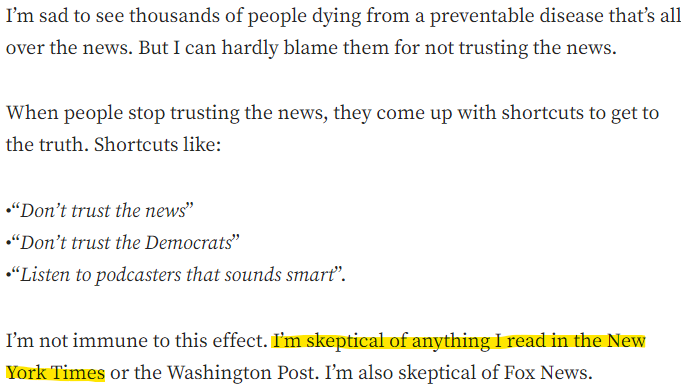

Most of this is just motivated reasoning by people who really want to blame scientists, then work backwards to try to come up with some way "they could have done it".

Most of this is just motivated reasoning by people who really want to blame scientists, then work backwards to try to come up with some way "they could have done it".

More than anything, I think this story shows that the intelligence agencies probably don't have any special information.

They have a few scientists, looking at the same data as everyone else is, subject to the same political biases as everyone else is.

They have a few scientists, looking at the same data as everyone else is, subject to the same political biases as everyone else is.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh