Why does Russia attack?

In 1991, Moscow faced two disobedient ethnic republics: Chechnya and Tatarstan. Both were the Muslim majority autonomies that refused to sign the Federation Treaty (1992), insisting on full sovereignty. In both cases, Moscow was determined to quell them.

In 1991, Moscow faced two disobedient ethnic republics: Chechnya and Tatarstan. Both were the Muslim majority autonomies that refused to sign the Federation Treaty (1992), insisting on full sovereignty. In both cases, Moscow was determined to quell them.

Still, the final outcome could not be more different. Chechnya was invaded, its towns razed to the ground, its leader assassinated. Tatarstan, on the other hand, managed to sign a favourable agreement with Moscow that lasted until Putin’s era.

The question is - why.

The question is - why.

Retrospectively, this course of events (obliterate Chechnya, negotiate with Tatarstan) may seem predetermined. But it was not considered as such back then. For many, including many of Yeltsin’s own partisans it came as a surprise, or perhaps even as a betrayal.

Let's see why

Let's see why

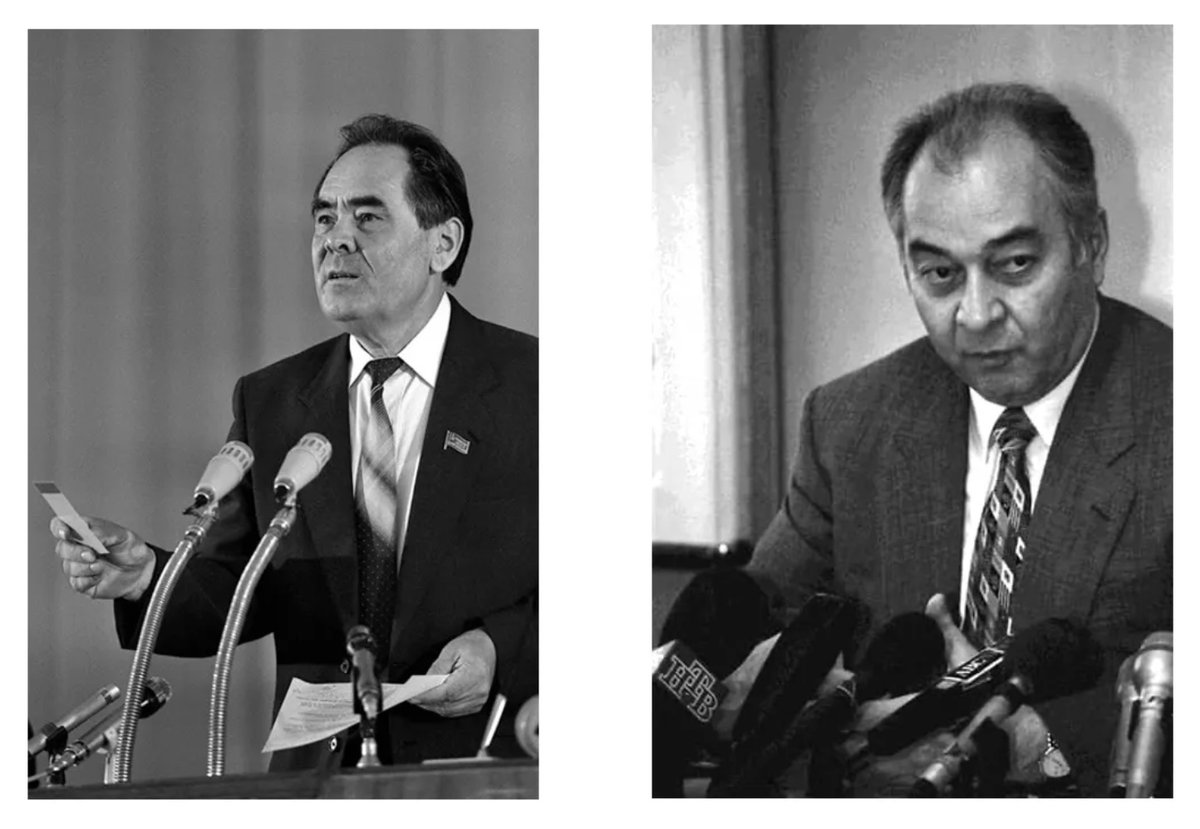

By the early 1991 - in the last days of the Soviet Union - both Tatarstan and Chechnya were run by their respective “First Secretaries”. That is Communist officials leading the local Communist organisation and running the region in the name of the Party.

That was the era of fierce and largely undercover struggle for power in Moscow. In that struggle, both Tatar and Chechen secretaries cautiously supported the opponents of Yeltsin, assuming they would win.

They were both mistaken. Yeltsin won.

They were both mistaken. Yeltsin won.

So what we have is a bunch of the Party secretaries scheming, plotting, entering into coalitions against each other, some of them winning, some of them losing.

In August 1991, one of these Party officials - the former First Secretary of Sverdlovsk - won, and ended on top.

In August 1991, one of these Party officials - the former First Secretary of Sverdlovsk - won, and ended on top.

Now simultaneously with a coup in Moscow, there was another coup happening - now in Chechnya.

Dzhokhar Dudaev had been a Soviet general of Chechen ethnicity. Basically, he commanded a division of strategic bombers that were responsible for a nuclear strike, just in case.

Dzhokhar Dudaev had been a Soviet general of Chechen ethnicity. Basically, he commanded a division of strategic bombers that were responsible for a nuclear strike, just in case.

Dudaev was a high-ranked Chechen military whom Yeltsin wanted to use as an ice breaker against the local Party organisation. In May 1991, Yeltsin's own deputy brought him to Chechnya

In a few months, he built an extensive power base there

In a few months, he built an extensive power base there

When the August 1991 hits, the First Secretary of Chechnya stands declares for the anti-Yeltsin’s forces, while Dudayev stands with Yeltsin. Within the few weeks, he overthrows the local First Secretary and assumes control over Chechnya.

So, when the Russian tanks rolled into Chechnya, and turned it into a pile rubles that came as a surprise to many Yeltsin’s supporters. Based on the experiences of 1991, they were used to see Yeltsin and Dudayev as a sort of pals in what they saw as a democratic revolution.

Let’s try to make out a model, explaining the actions of Yeltsin

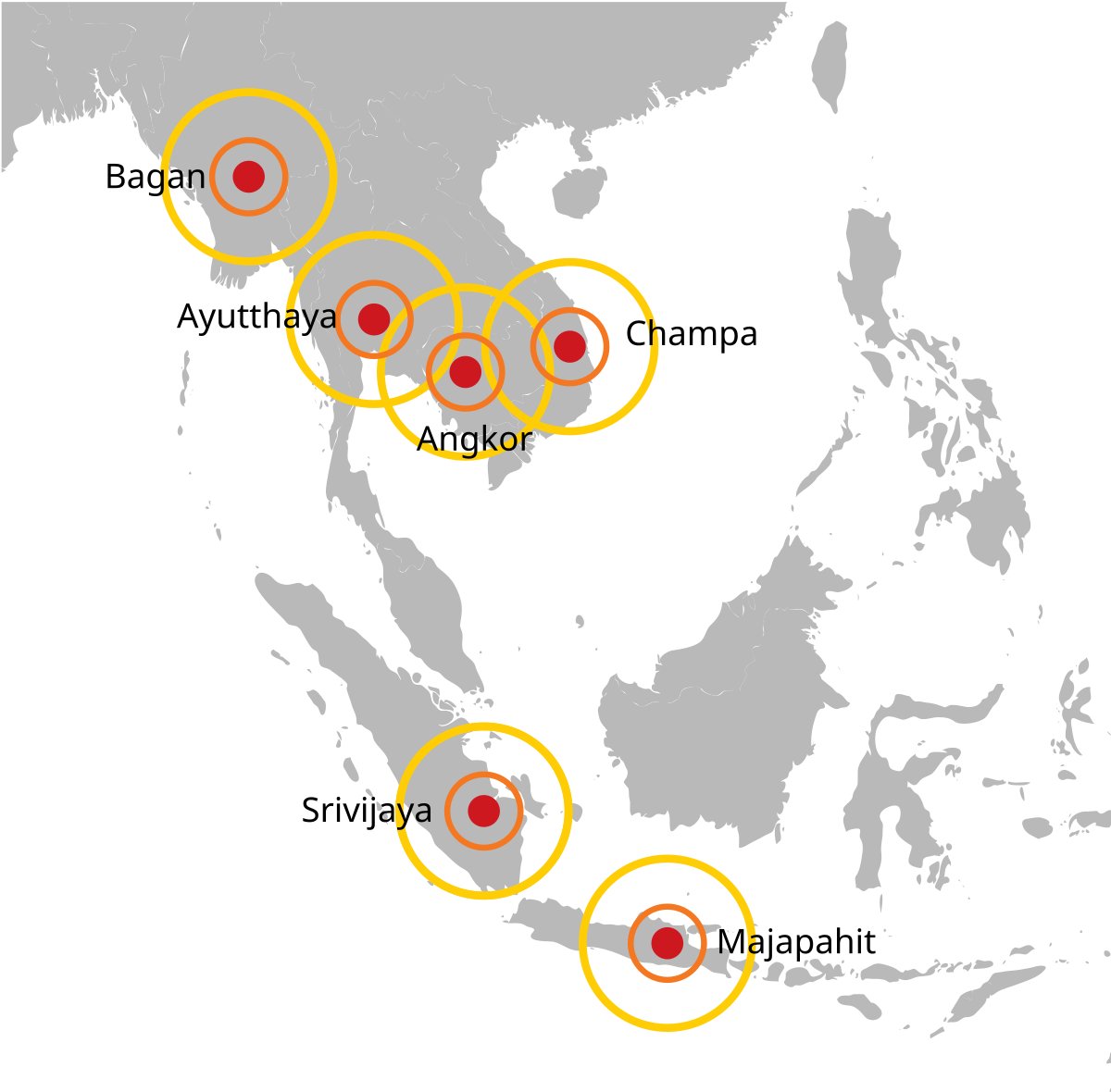

I suggest mandala. The model of distributed political authority parallel to what we had in the classic and medieval South and Southeast Asia

I suggest mandala. The model of distributed political authority parallel to what we had in the classic and medieval South and Southeast Asia

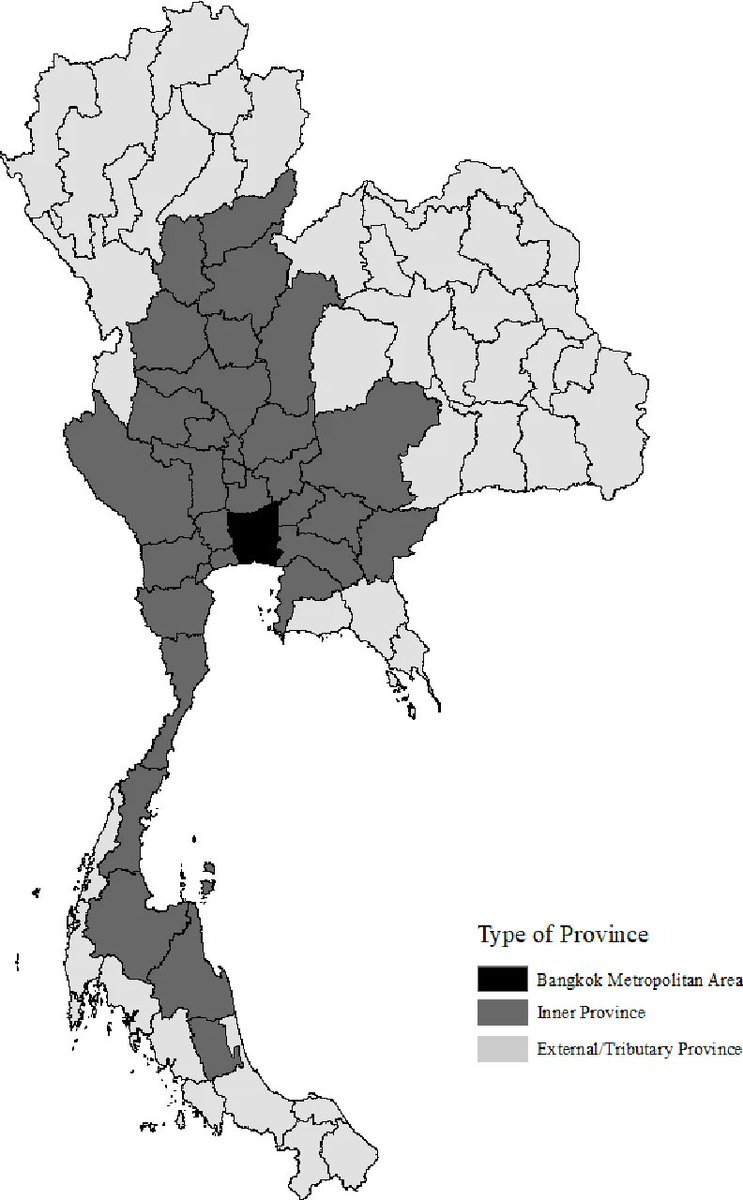

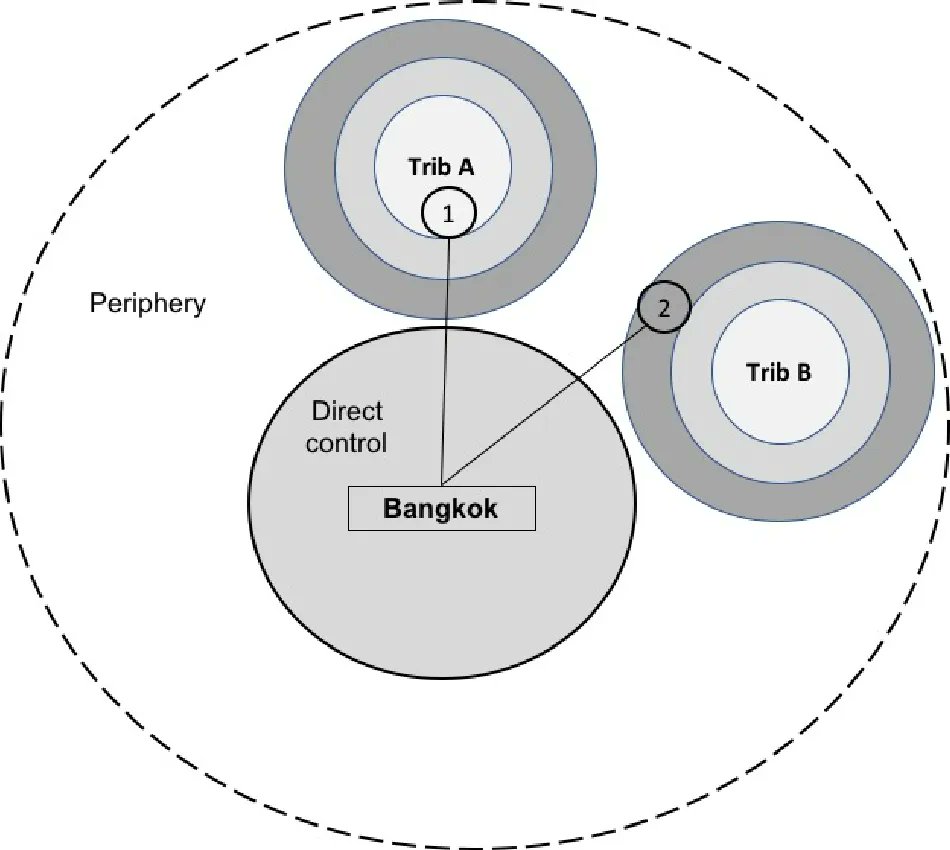

Basically, there is a kingdom. Let’s say Thailand

You have the metropole. You have core provinces. You have tributaries. The further away from the centre, the looser the control.

You can frame it as a collection of districts engaged into the bilateral relations with the centre

You have the metropole. You have core provinces. You have tributaries. The further away from the centre, the looser the control.

You can frame it as a collection of districts engaged into the bilateral relations with the centre

So, basically you can represent Thailand as a number of districts, presided by the district of Bangkok, and all involved into the bilateral relations with Bangkok

(on highly unequal and varying conditions)

(on highly unequal and varying conditions)

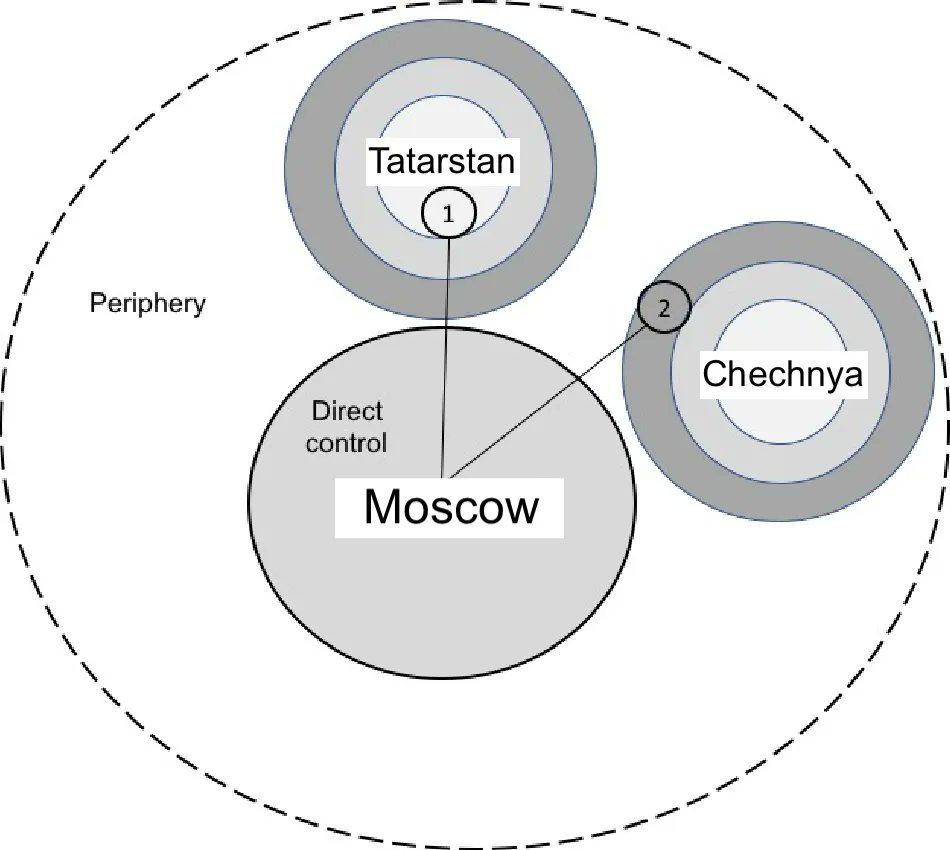

Now let’s apply the same scheme to Russia

The suzerain district of Moscow has bilateral relations with vassal districts of Chechnya and Tatarstan

Now the thing to understand is that the relations between these districts are not purely "diplomatic", and are not purely personal.

The suzerain district of Moscow has bilateral relations with vassal districts of Chechnya and Tatarstan

Now the thing to understand is that the relations between these districts are not purely "diplomatic", and are not purely personal.

The thing with these districts is that they are not sealed from each other. So, the internal developments in one district - let's say Chechnya - affect the internal political balance in the district of Moscow.

People are governed by impressions. One reason of why Moscow might want to destroy a vassal principality is not that its leader is “unfriendly” or is dealing with the foreign enemies, but simply that the internal happenings in that district produce wrong effect in Moscow itself.

What the Muscovites see in Chechnya can and does affect the political situation in Moscow.

And what do the Muscovites see in Chechnya?

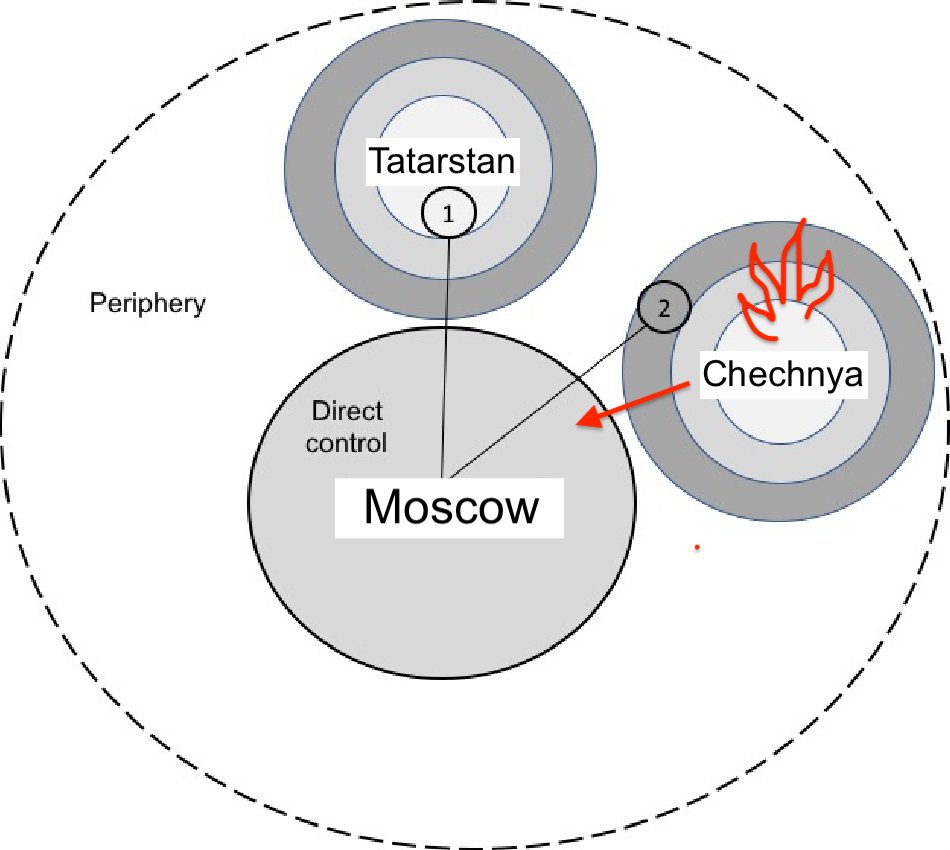

They see that the military can do a political takeover.

And what do the Muscovites see in Chechnya?

They see that the military can do a political takeover.

A military general can execute a coup and get away with that

That is the main political takeaway the people in Moscow draw from Chechnya

And, even worse, the generals in Moscow do

That is the main political takeaway the people in Moscow draw from Chechnya

And, even worse, the generals in Moscow do

Since 1917, control over the army had been the No. 1 concern of any Russian regime. The military had to absolutely submit to the political leadership, and not be allowed even a grain of power. They leadership knew very well that you they give them a bit, they would take it all.

And Yeltsin knew very well, that the only threat to his regime comes from his own military. And that was the problem with Dudaev

He took a pro-Yeltsin stance. He overthrew an anti-Yeltsin party secretary

He took a pro-Yeltsin stance. He overthrew an anti-Yeltsin party secretary

BUT

The idea that a military can overthrow a politician and take his place - in any - absolutely any district of Yeltsin’s mandala was a direct challenge, direct threat to the Yeltsin’s rule over the district of Moscow. Because it was giving wrong ideas to his own generals.

The idea that a military can overthrow a politician and take his place - in any - absolutely any district of Yeltsin’s mandala was a direct challenge, direct threat to the Yeltsin’s rule over the district of Moscow. Because it was giving wrong ideas to his own generals.

Chechnya had to be destroyed because it showed a successful example of a military coup. The idea that a military general can displace a local bureaucrat by force would be giving very wrong and harmful ideas to the Yeltsin's military endangering his rule over Moscow.

Again, comparison with Tatarstan can be very telling.

In 1991, the First Secretary of Tatarstan declared against Yeltsin. Yet, that did not prevent their later rapprochement, because the very fact of his rule over Kazan did not endanger or undermine Yeltsin's rule over Moscow.

In 1991, the First Secretary of Tatarstan declared against Yeltsin. Yet, that did not prevent their later rapprochement, because the very fact of his rule over Kazan did not endanger or undermine Yeltsin's rule over Moscow.

If I were to give a short summary of this text, I would say that Corinth can be hostile to Athens simply because the internal political dynamics of Athens give wrong ideas to the citizens of Corinth, even without Athens harbouring any hostile intentions.

kamilkazani.substack.com/p/why-did-yelt…

kamilkazani.substack.com/p/why-did-yelt…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh