The Ethiopian Ruler of Maharashtra

Malik Ambar, buried a five minute walk from the Ellora Caves, is of the most extraordinary figures in world history.

Malik Ambar, buried a five minute walk from the Ellora Caves, is of the most extraordinary figures in world history.

Born with the name 'Chapu" in Har into Ethiopia's Oromo tribe, Ambar was "captured as a boy and sold to an Arab for twenty ducats."

"He has a stern Roman face" recalled one traveller, "and is tall and strong of stature", thought his white glassy eyes... do not become him."

"He has a stern Roman face" recalled one traveller, "and is tall and strong of stature", thought his white glassy eyes... do not become him."

Chapu was evenutally sold to the Peshwa (Chief Minister) of Ahmednagar - a man who was himself a former Ethiopian slave. Five years later, the Peshwa died and the Peshwa's widow finally granted Malik Ambar his freedom.

Ambar became the leader of a mercenary squad.

Then all of a sudden the Mughals conquered Ahmadnagar and Malik Ambar launched a resistance movement to place a scion of the Nizam Shahi dynasty back on the throne.

Then all of a sudden the Mughals conquered Ahmadnagar and Malik Ambar launched a resistance movement to place a scion of the Nizam Shahi dynasty back on the throne.

Ambar attracted Dakhni and Marathi speakers alike and, with a certain Maloji Bhonsle by his side, Ambar soon emerged as de facto ruler of the former kingdom of Ahmadnagar.

Much of modern Maharashtra was now simply reffered to as "Ambar's land".

Seen here: Malojis samadhi

Much of modern Maharashtra was now simply reffered to as "Ambar's land".

Seen here: Malojis samadhi

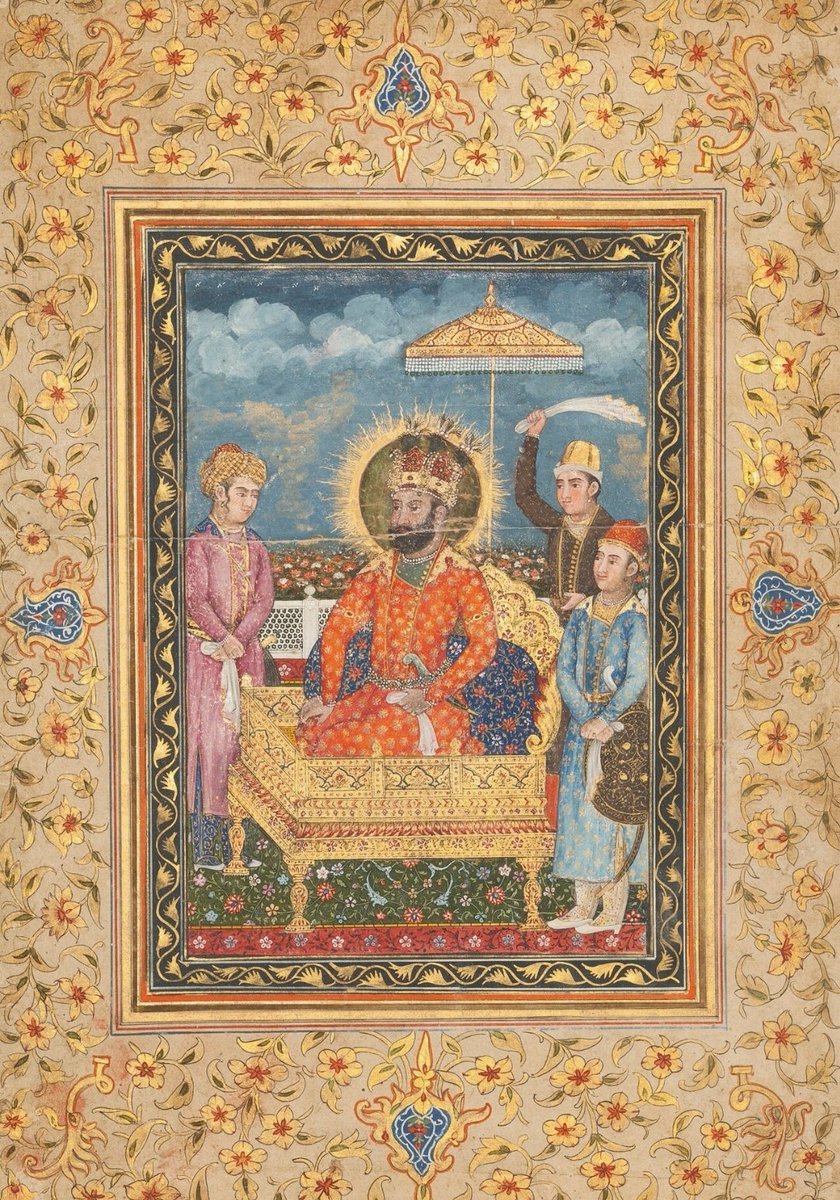

As the Mughal Emperor Jahangir took to throne in Agra, he considered Malik Ambar his greatest foe.

Indeed Jahangir commisioned a painting of himself shooting Malik Ambar in the face.

Indeed Jahangir commisioned a painting of himself shooting Malik Ambar in the face.

For the full story, do read my substack article below!

travelsofsamwise.substack.com/p/ahmadnagar-a…

travelsofsamwise.substack.com/p/ahmadnagar-a…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh