Everythingism.

The belief that every policy is a means for promoting every other policy, all at the same time. Everythingism it’s why nothing works.

Defeating Everythingism is the only way we can start to fix everything.

This essay explains how.

The belief that every policy is a means for promoting every other policy, all at the same time. Everythingism it’s why nothing works.

Defeating Everythingism is the only way we can start to fix everything.

This essay explains how.

Because of Everythingism, we distort some policies to further other policies which they are fundamentally unsuited to.

Trains are for protecting bats.

samdumitriu.com/p/have-we-solv…

Trains are for protecting bats.

samdumitriu.com/p/have-we-solv…

Energy policy is for promoting different languages

https://x.com/SCP_Hughes/status/1887828812387471708

Because of Everythingism we never do one thing well, we do everything badly. Because whilst these are all good objectives, often they’re at odds with each other. Sometimes the trade-offs are worth it, but often they aren’t.

In the US @EzraKlein originally called this ‘Everything Bagel Liberalism’ - the propensity for blue states and particularly big cities to layer so many requirements on policies that nothing gets done.

nytimes.com/2023/04/02/opi…

nytimes.com/2023/04/02/opi…

But in Britain, letting the perfect policy be the enemy of the good is a cross-party issue, and as much bureaucratic as it is political.

Everyone loses from Everythingism. It creates many excuses for inaction, and many veto players, who can frustrate the aims of governments.

Now, the world is complex, and policy needs to account for that, and unintended consequences. But complexity is good for describing issues, not for acting. Instead, in government policymakers are usually rewarded for making policies as complex and interdependent as possible.

Everythingism leads to distraction, what Louise Casey called “initiativits”, where government becomes so obsessed with how its own plans work that it can’t decisively act in new ways.

newstatesman.com/spotlight/econ…

newstatesman.com/spotlight/econ…

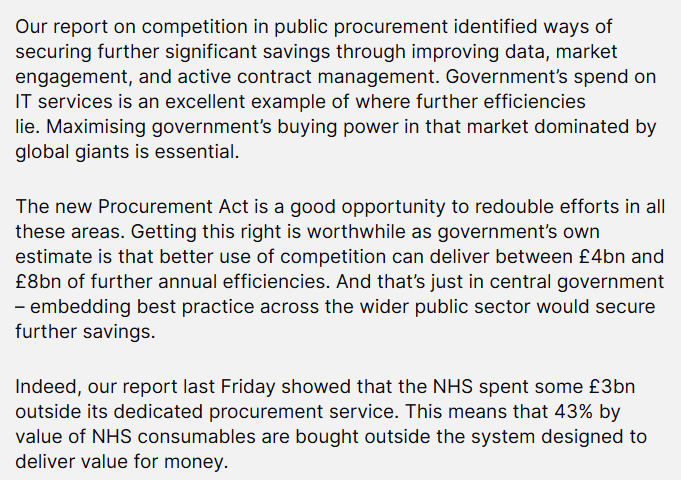

Everythingism means policymakers deny tradeoffs. Procurement in Britain trades off getting good value for money against vague metrics for 'social value', priced at 10% of the marks for any tender. These have not worked internationally

https://x.com/EricCrampton/status/1903899377904795881

Everythingism paralyses institutions. It creates a “kludgeocracy” which means nothing gets done because of the accreted and interdependent layers of policy.

https://x.com/hamandcheese/status/1067619186548097024

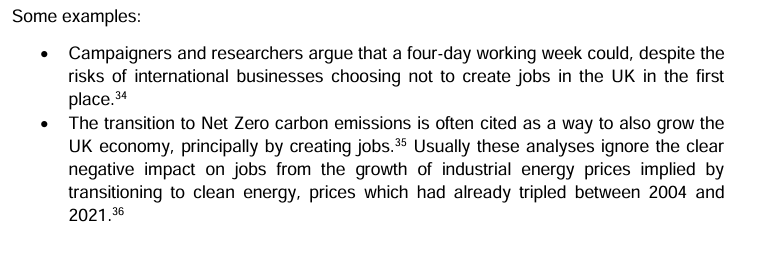

Everythingism is supported by an implicit belief that all good things correlate, all the time. This is a handy meme for policymakers to believe, but usually it’s false.

Everythingism makes systems unaccountable. And indeed this is preferable for people in those systems – if every policy is about every other policy, then it’s hard to blame any one policymaker for failing.

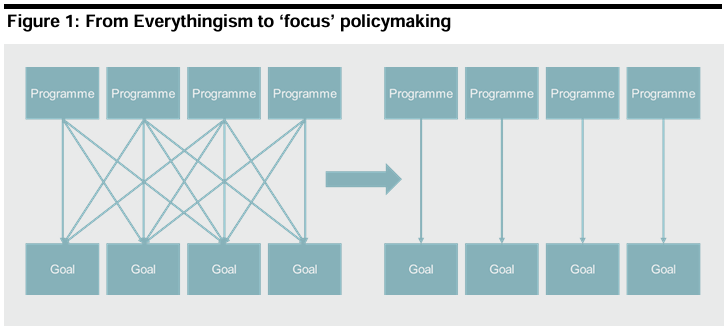

Instead of Everythingism, we need to embrace radical focus in policymaking. Using the best levers to promote a policy, and only those. The economic literature bears this approach out over the confusion of Everythingism.

If we can beat Everythingism, then there is a chance we can start to fix everything that’s going wrong.

You can read the full essay here reform.uk/publications/e…

You can read the full essay here reform.uk/publications/e…

Particular thanks to @bswud, @pdmsero, @antonhowes for their advice and input, and especially to Anton for coining the term!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh