In 793 AD, monks watched in horror as Viking longships emerged from the fog at Lindisfarne.

By sunset, the monastery lay in ruins — but the real conquest was just beginning.

These raiders would transform not just England's fate, but the very words we speak today...🧵

By sunset, the monastery lay in ruins — but the real conquest was just beginning.

These raiders would transform not just England's fate, but the very words we speak today...🧵

These invaders changed English forever.

Words like “sky, “window,” and “husband” all came from Vikings — even the word “they.”

About 5% of our vocabulary is Norse — but it's an essential 5%

Their impact runs deeper than any other linguistic influence in the history of English.

Words like “sky, “window,” and “husband” all came from Vikings — even the word “they.”

About 5% of our vocabulary is Norse — but it's an essential 5%

Their impact runs deeper than any other linguistic influence in the history of English.

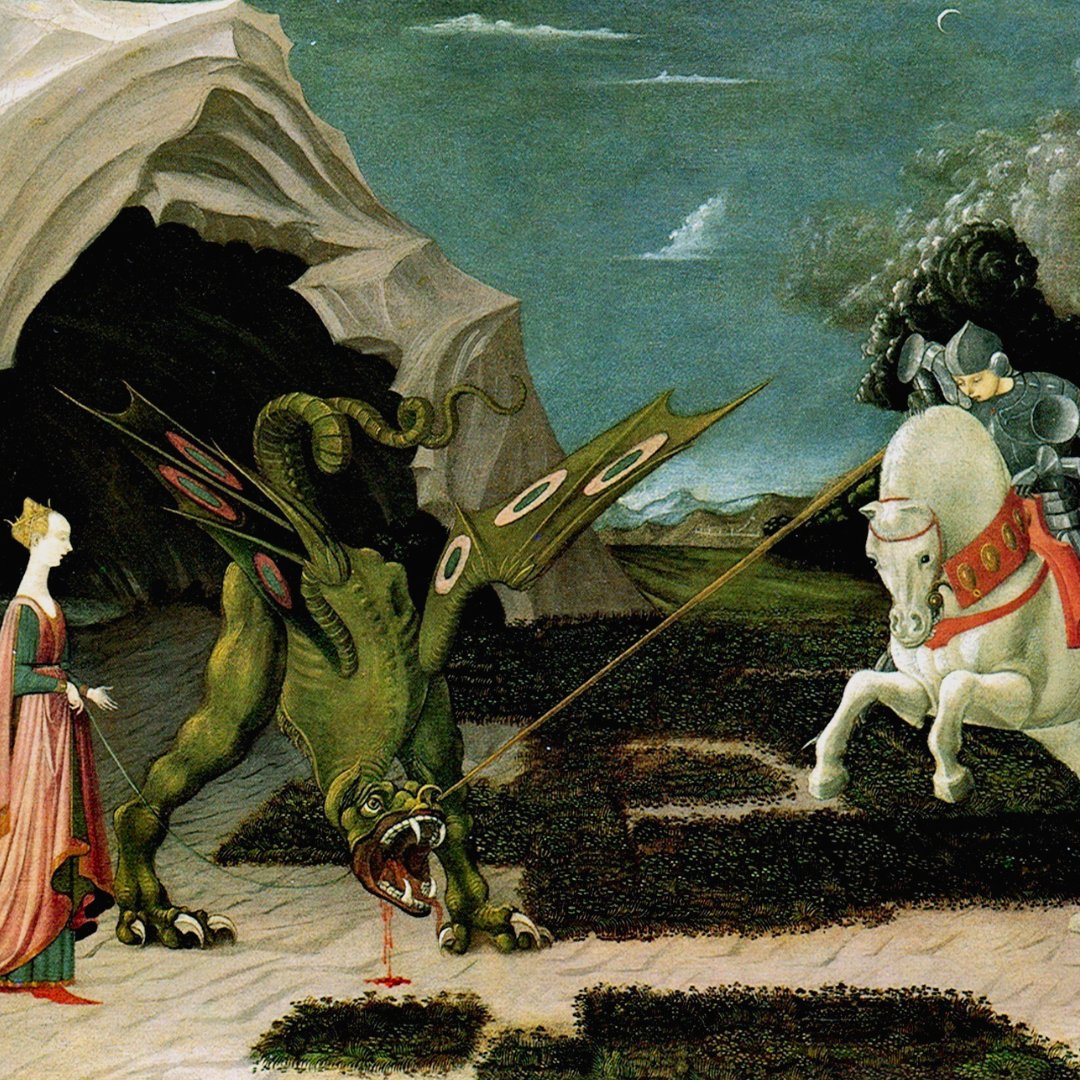

It all began at Lindisfarne in 793 AD — a centre of English Christianity.

For months, omens had swept across the land — whirlwinds, lightning on clear days, dragons in the night sky.

When Viking longships appeared through the morning mist, these warnings made terrible sense.

For months, omens had swept across the land — whirlwinds, lightning on clear days, dragons in the night sky.

When Viking longships appeared through the morning mist, these warnings made terrible sense.

By nightfall, the great monastery was spattered with the blood of its monks.

Priceless manuscripts reduced to ash. Holy relics stolen.

This was the heart of Christian England — if it could fall, what would remain standing?

No one knew this was just the beginning.

Priceless manuscripts reduced to ash. Holy relics stolen.

This was the heart of Christian England — if it could fall, what would remain standing?

No one knew this was just the beginning.

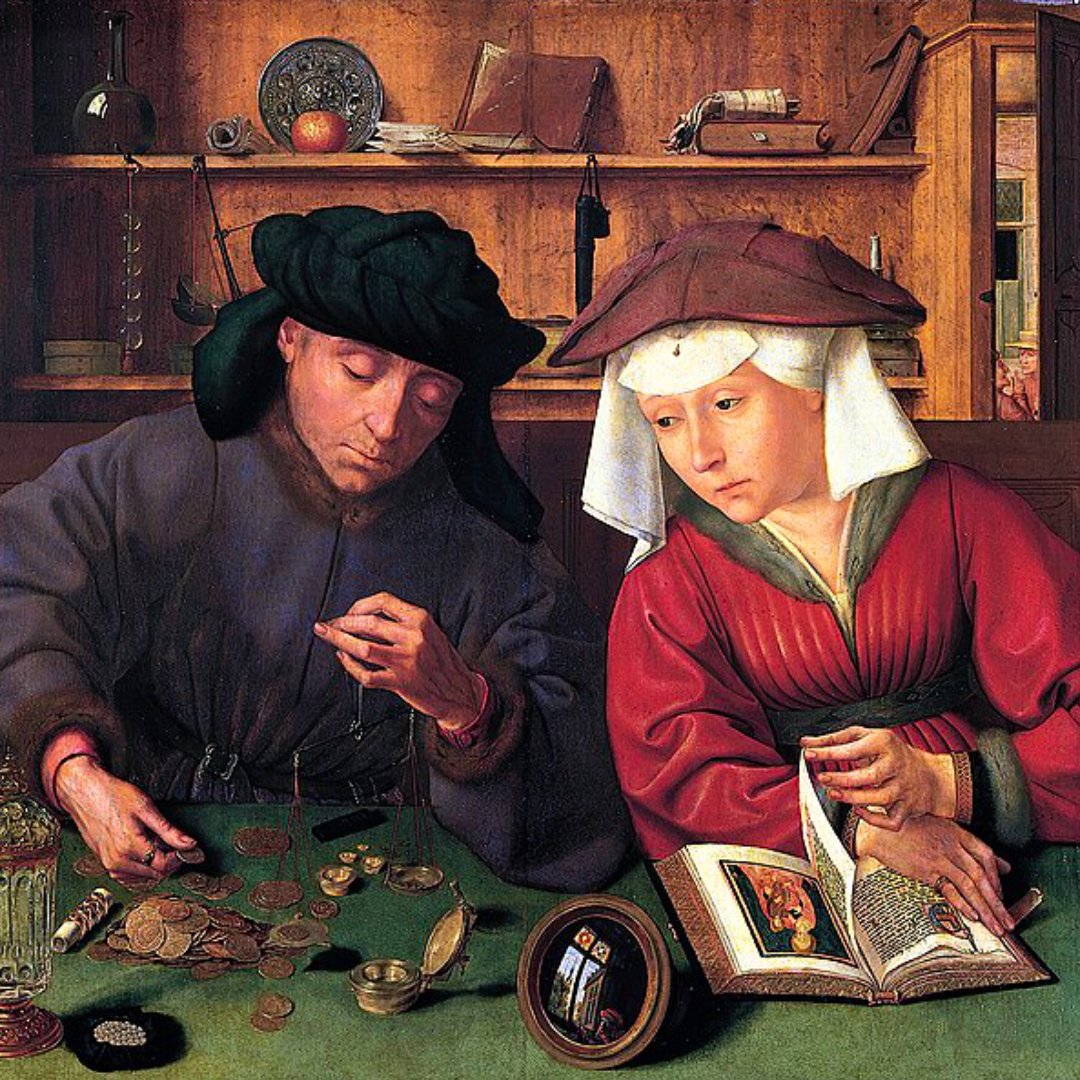

What started as raids transformed into settlement.

Within a century, Vikings weren't just visiting — they were farming, trading, and marrying locals.

By 886, King Alfred recognized their control over northern England.

The Danelaw was born — a Norse kingdom within England.

Within a century, Vikings weren't just visiting — they were farming, trading, and marrying locals.

By 886, King Alfred recognized their control over northern England.

The Danelaw was born — a Norse kingdom within England.

This vast territory became a linguistic melting pot.

Old English and Old Norse speakers lived side by side for generations.

Unlike the later Normans, who ruled from above, Vikings mixed with everyday folk.

Their languages blended in ways that would change how English works.

Old English and Old Norse speakers lived side by side for generations.

Unlike the later Normans, who ruled from above, Vikings mixed with everyday folk.

Their languages blended in ways that would change how English works.

What made this mixing unique was how closely related these languages were.

Both were Germanic, so their speakers could understand each other — with effort.

It was the perfect recipe for a deep transformation of the English language...

Both were Germanic, so their speakers could understand each other — with effort.

It was the perfect recipe for a deep transformation of the English language...

Soon, Norse words replaced native English terms.

Old English “heofon” gave way to “sky.” “Niman” was replaced by “take.”

Most remarkably, Vikings gave English the words “they,” “them,” and “their.”

It's very rare for languages to borrow such fundamental words.

Old English “heofon” gave way to “sky.” “Niman” was replaced by “take.”

Most remarkably, Vikings gave English the words “they,” “them,” and “their.”

It's very rare for languages to borrow such fundamental words.

Old English grammar was complex like modern German — as was Old Norse.

Words took on countless endings — and they weren't optional.

But after the languages mixed, these endings disappeared.

The need to communicate across language barriers may have streamlined English grammar.

Words took on countless endings — and they weren't optional.

But after the languages mixed, these endings disappeared.

The need to communicate across language barriers may have streamlined English grammar.

Unlike others, the Vikings changed English from the inside.

French gave English fancy terms, but Norse affected how you talk about everyday life.

When you look through a “window” at the “sky” — not an “eyethurl” at the “heavens” — you're speaking the language the Norse built.

French gave English fancy terms, but Norse affected how you talk about everyday life.

When you look through a “window” at the “sky” — not an “eyethurl” at the “heavens” — you're speaking the language the Norse built.

If you found this thread interesting, you may also enjoy my free newsletter.

In the latest issue, I dive even deeper into how contact with Old Norse changed the English language.

Join the Dead Language Society 💀📚👇

deadlanguagesociety.com

In the latest issue, I dive even deeper into how contact with Old Norse changed the English language.

Join the Dead Language Society 💀📚👇

deadlanguagesociety.com

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh