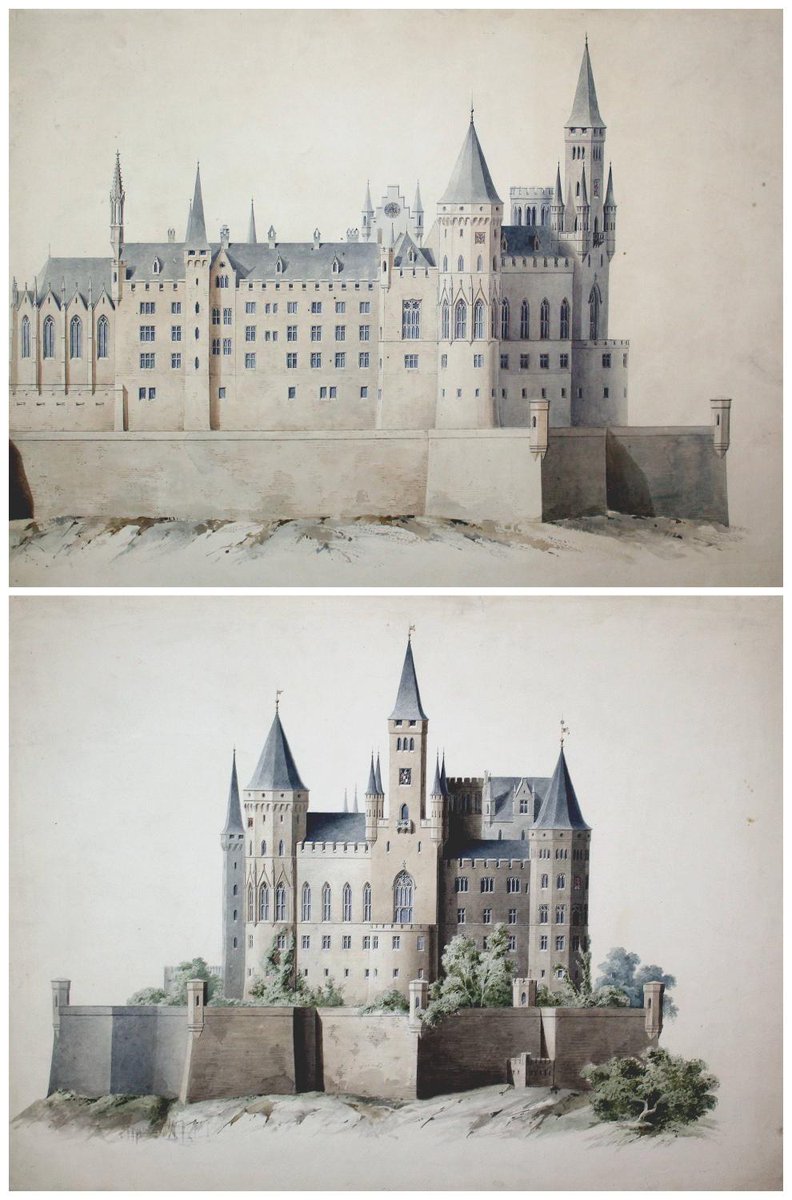

This is Burg Hohenzollern in Germany, one of the world's most beautiful Medieval castles.

Except that it isn't a Medieval castle — trains had been invented before it was built.

And so Hohenzollern is a perfect introduction to Neo-Gothic Architecture...

Except that it isn't a Medieval castle — trains had been invented before it was built.

And so Hohenzollern is a perfect introduction to Neo-Gothic Architecture...

If you want to understand Neo-Gothic Architecture then the best place to begin is with something like Hohenzollern.

It seems too good to be true — and that's because it is.

What you're looking at here isn't a Medieval castle; it's not even 200 years old.

It seems too good to be true — and that's because it is.

What you're looking at here isn't a Medieval castle; it's not even 200 years old.

There has been some kind of fortification on this hill, at the edge of the Swabian Alps, for over one thousand years.

An 11th century castle was destroyed and replaced in the 15th century, but that second castle soon fell into ruin.

An 11th century castle was destroyed and replaced in the 15th century, but that second castle soon fell into ruin.

During the 19th century the owners of this ruined castle — the noble House of Hohenzollern, a German imperial family — decided to build something new.

It would be both a residence and a monument to their family and its long history.

It would be both a residence and a monument to their family and its long history.

Thus a new "castle" was built between 1846 and 1867 under the architect Friedrich August Stüler.

But it was only a castle in appearance — this is not a real military fortification, as Medieval castles were.

It is, instead, an architectural fantasy inspired by the Middle Ages.

But it was only a castle in appearance — this is not a real military fortification, as Medieval castles were.

It is, instead, an architectural fantasy inspired by the Middle Ages.

And what a fantasy!

This is a labyrinth of chapels, staircases, ramparts, and ballrooms, filled with painted vaults and sculptures and stained glass windows.

But, as said, it's worth remembering that trains and electricity were around before any of this was done.

This is a labyrinth of chapels, staircases, ramparts, and ballrooms, filled with painted vaults and sculptures and stained glass windows.

But, as said, it's worth remembering that trains and electricity were around before any of this was done.

It also rises majestically above the surrounding landscape, like something from a film.

This location was once a defensive necessity, but by the 19th century it had become — although still symbolically and politically important for the Hohenzollerns — purely aesthetic.

This location was once a defensive necessity, but by the 19th century it had become — although still symbolically and politically important for the Hohenzollerns — purely aesthetic.

Hohenzollern was built during the Gothic Revival, as architects across Europe turned their back on the Neoclassical Architecture of the 18th century and embraced the Middle Ages.

Construction on the new Palace of Westminster in London had only started ten years before.

Construction on the new Palace of Westminster in London had only started ten years before.

And, shortly after Hohenzollern, the most famous achievement of this Neo-Gothic Age was built: Neuschwanstein.

This was the project of King Ludwig II of Bavaria, a rich and eccentric but powerless king who lived in a dreamworld of chivalrous knights and fair maidens.

This was the project of King Ludwig II of Bavaria, a rich and eccentric but powerless king who lived in a dreamworld of chivalrous knights and fair maidens.

But the Gothic Revival of the 19th century wasn't only about architectural fantasy castles.

There were also train stations, like Gilbert Scott's St Pancras, along with courts, schools, churches, libraries, bridges, and... regular houses.

There were also train stations, like Gilbert Scott's St Pancras, along with courts, schools, churches, libraries, bridges, and... regular houses.

Not to forget skyscrapers!

Because the Gothic Revival didn't end in the 19th century — in the United States it lived on through to the Age of Skyscrapers.

Consider Tribune Tower in Chicago, the Woolworth Building in New York, or (below) the Cathedral of Learning in Pittsburgh.

Because the Gothic Revival didn't end in the 19th century — in the United States it lived on through to the Age of Skyscrapers.

Consider Tribune Tower in Chicago, the Woolworth Building in New York, or (below) the Cathedral of Learning in Pittsburgh.

There were also Neo-Gothic water towers.

Even infrastructure which was purely functional represented to the architects and urban planners of the 19th century an opportunity for turrets, trefoils, and pointed arches.

Neo-Gothic was everywhere.

Even infrastructure which was purely functional represented to the architects and urban planners of the 19th century an opportunity for turrets, trefoils, and pointed arches.

Neo-Gothic was everywhere.

But why is Hohenzollern — and the Gothic Revival generally — still important?

Because those who built and designed these structures weren't obliged or forced to imitate the architecture of the Middle Ages.

They chose to do so.

Because those who built and designed these structures weren't obliged or forced to imitate the architecture of the Middle Ages.

They chose to do so.

The Gothic Revival in architecture was part of a broader resurgence of interest in the Middle Ages.

Whether in literature — Walter Scott or Byron — or in art — the Pre-Raphaelites or Caspar David Friedrich — or music — Richard Wagner.

Medievalism was wildly popular.

Whether in literature — Walter Scott or Byron — or in art — the Pre-Raphaelites or Caspar David Friedrich — or music — Richard Wagner.

Medievalism was wildly popular.

So, despite any and all other considerations, whether economic or political, there was demand for Neo-Gothic architecture — and so that is what they built.

They didn't copy Medieval architecture; modern materials and methods were used.

But the people got what they wanted.

They didn't copy Medieval architecture; modern materials and methods were used.

But the people got what they wanted.

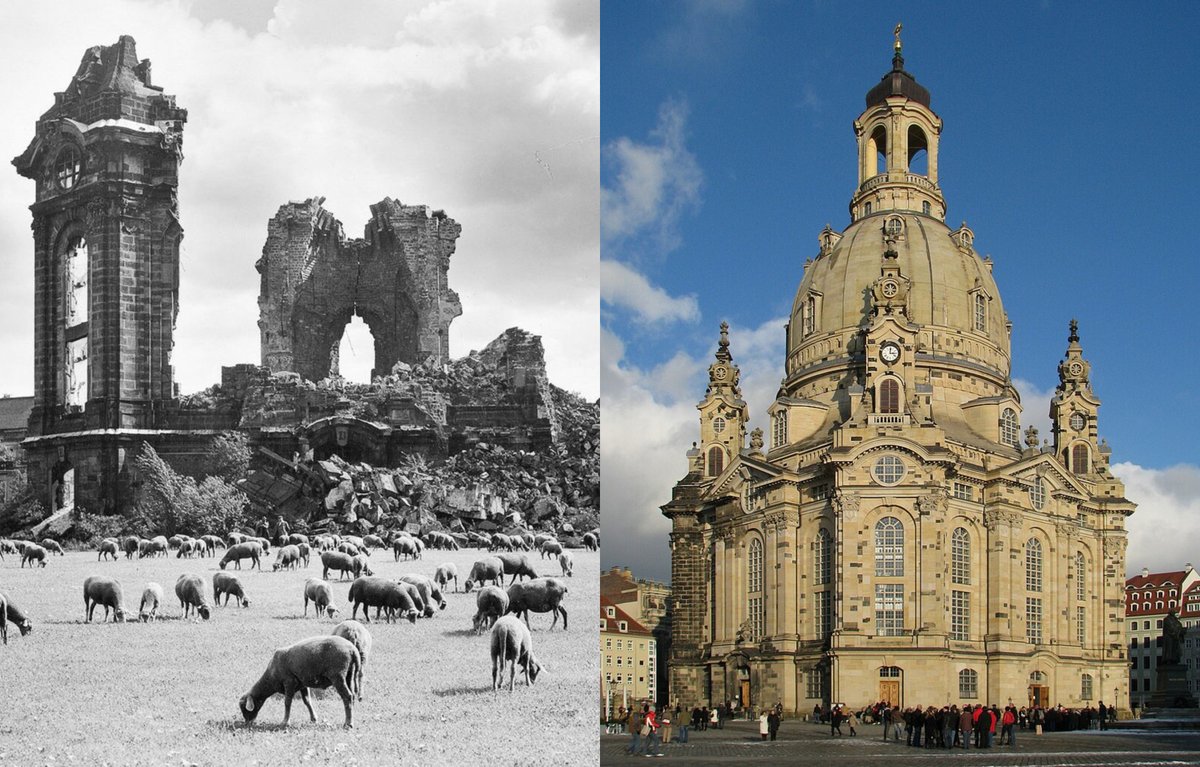

You don't get architecture unless you want it — conviction and desire is always the first step.

Consider the Frauenkirche in Dresden, rebuilt less than 30 years ago after being destroyed in WWII.

Or the Great Cloth Hall of Ypres, destroyed during WWI and rebuilt in the 1960s.

Consider the Frauenkirche in Dresden, rebuilt less than 30 years ago after being destroyed in WWII.

Or the Great Cloth Hall of Ypres, destroyed during WWI and rebuilt in the 1960s.

Or Kinkaku-ji, a 600 year old temple burned down in the 1950s and immediately reconstructed.

Or the ancient Yellow Crane Tower in Wuhan, rebuilt in the 1980s.

Or St Mark's Campanile in Venice, once Medieval but rebuilt in 1912 after it collapsed.

Or the ancient Yellow Crane Tower in Wuhan, rebuilt in the 1980s.

Or St Mark's Campanile in Venice, once Medieval but rebuilt in 1912 after it collapsed.

Or even the four thousand year old Ziggurat of Ur in Iraq, which was partially reconstructed in the 1980s.

In all cases these were "historical" styles of architecture, and yet it was somehow possible to build in those styles...

In all cases these were "historical" styles of architecture, and yet it was somehow possible to build in those styles...

Millions around the world are not happy about what we loosely call "modern architecture".

Regardless of exactly which historical style they like — Gothic, Rajput, Umayyad, Baroque, or Safavid — people generally prefer old architecture.

Just look where tourists take photos.

Regardless of exactly which historical style they like — Gothic, Rajput, Umayyad, Baroque, or Safavid — people generally prefer old architecture.

Just look where tourists take photos.

And yet, they are told, it is simply impossible to build like that anymore.

Maybe that's true, but Hohenzollern and all these other buildings from around the world, regardless of their "style", remind us that such architecture is possible if we actually want to build it.

Maybe that's true, but Hohenzollern and all these other buildings from around the world, regardless of their "style", remind us that such architecture is possible if we actually want to build it.

Just look at Huawei's Ox Horn Campus in Dongguan, which was opened less than ten years ago.

Each area of this vast office complex is inspired by the architecture of a different European city, such as Bruges, Oxford, or Verona.

Each area of this vast office complex is inspired by the architecture of a different European city, such as Bruges, Oxford, or Verona.

Or the Swaminarayan Akshardham in Delhi, a colossal and traditionally built temple that looks like it should be at least one thousand years old.

It was started in 2001 and finished in 2005.

It was started in 2001 and finished in 2005.

You could explore the rise of Neo-Gothic in terms of how Medieval methods were reinterpreted, which specific styles were resurrected, and how they controversially restored old buildings.

But the true heart of the Gothic Revival was the simple conviction to build that way.

But the true heart of the Gothic Revival was the simple conviction to build that way.

There are plenty of fascinating challenges and complex questions here, whether of the economics or the engineering of particular style, but they are all downstream of the desire and decision to actually build with it.

And that is one of the eternal truths of architecture.

And that is one of the eternal truths of architecture.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh