One of the darkest hours in the Vatican’s history

The brief 33-day papacy of John Paul I

His sudden death in September 1978 remains shrouded in mystery, doubts, and speculation

A Thread 🧵

The brief 33-day papacy of John Paul I

His sudden death in September 1978 remains shrouded in mystery, doubts, and speculation

A Thread 🧵

Albino Luciani, born in 1912 in Canale d’Agordo, Italy, became Pope John Paul I on August 26, 1978

His election was swift, concluded in a single day, with 101 out of 111 cardinals voting for him

He chose a double name to honor his predecessors, John XXIII and Paul VI

His election was swift, concluded in a single day, with 101 out of 111 cardinals voting for him

He chose a double name to honor his predecessors, John XXIII and Paul VI

Despite lasting only 33 days, Luciani stood out for his modesty and simplicity

He rejected traditional symbols of papal power, like the tiara and “sedia gestatoria”, and dropped the royal “we,” speaking in the first person

Humility in his voice

He rejected traditional symbols of papal power, like the tiara and “sedia gestatoria”, and dropped the royal “we,” speaking in the first person

Humility in his voice

Albino Luciani, the humble son of a Venetian bricklayer, became Pope while remaining a pastoral and gentle figure who charmed the world with his warm smile

Nicknamed “The Smiling Pope” because his smile was constant and eternal in every occasion

Nicknamed “The Smiling Pope” because his smile was constant and eternal in every occasion

Luciani quickly clashed with powerful figures, notably Archbishop Paul Marcinkus, head of the Vatican Bank, which was embroiled in shady financial dealings

The Pope sought to reform the IOR and remove Marcinkus who had ties to controversial figures associated with a Masonic lodge

The Pope sought to reform the IOR and remove Marcinkus who had ties to controversial figures associated with a Masonic lodge

A list of alleged Freemasons in the Vatican, published just before his death, reportedly disturbed him, hinting at internal resistance to his reforms

But then came an unexpected death

On the night of September 28–29, 1978, Luciani was found dead in his bed by Sister Margherita Marin and Sister Vincenza Taffarel

The official report cited a heart attack, but no autopsy was performed, as it wasn’t customary for Popes

On the night of September 28–29, 1978, Luciani was found dead in his bed by Sister Margherita Marin and Sister Vincenza Taffarel

The official report cited a heart attack, but no autopsy was performed, as it wasn’t customary for Popes

Contradictions soon emerged: the Vatican initially claimed his secretary, John Magee, found the body, omitting the nuns’ role

Conflicting accounts of his final hours—some mentioning ignored chest pain, others describing him as calm—fueled suspicion

(Sister Margherita)

Conflicting accounts of his final hours—some mentioning ignored chest pain, others describing him as calm—fueled suspicion

(Sister Margherita)

Several theories surfaced over the years

In God’s Name (1984), David Yallop suggested Luciani was poisoned with digitalis by M., V., and C., in collusion with C., S., and G., to halt IOR reforms

In God’s Name (1984), David Yallop suggested Luciani was poisoned with digitalis by M., V., and C., in collusion with C., S., and G., to halt IOR reforms

In 2019, A. R. claimed he helped M. to kill the Pope using valium and cyanide to cover up a financial fraud

Others, like theologian Giovanni Gennari, proposed a medication error, while John Cornwell’s “A Thief in the Night” attributed the death to stress and heart issues, though noting odd details like the Pope’s torn vestments

Luciani had a history of health issues, including tuberculosis in his youth, low blood pressure, and vascular problems

Yet his physician, Antonio Da Ros, described him as healthy during his pontificate, and his brother Edoardo denied serious heart conditions

Yet his physician, Antonio Da Ros, described him as healthy during his pontificate, and his brother Edoardo denied serious heart conditions

The absence of an autopsy and the Vatican’s poor communication deepened suspicions

In 2022, Stefania Falasca, vice-postulator for his beatification, argued it was a natural death from a heart attack, citing medical records, but conspiracy theories persist

In 2022, Stefania Falasca, vice-postulator for his beatification, argued it was a natural death from a heart attack, citing medical records, but conspiracy theories persist

It’s not hard to sketch a conspiracy theory about those years, where figures like C., S., G., M., and many others form a tangled web of powers, secret services, and international intrigues

Despite its brevity, Luciani was greatly loved, and his pontificate left a mark through his humanity and vision for a simpler, more accessible Church

Pope Luciani remained a simple, humble figure

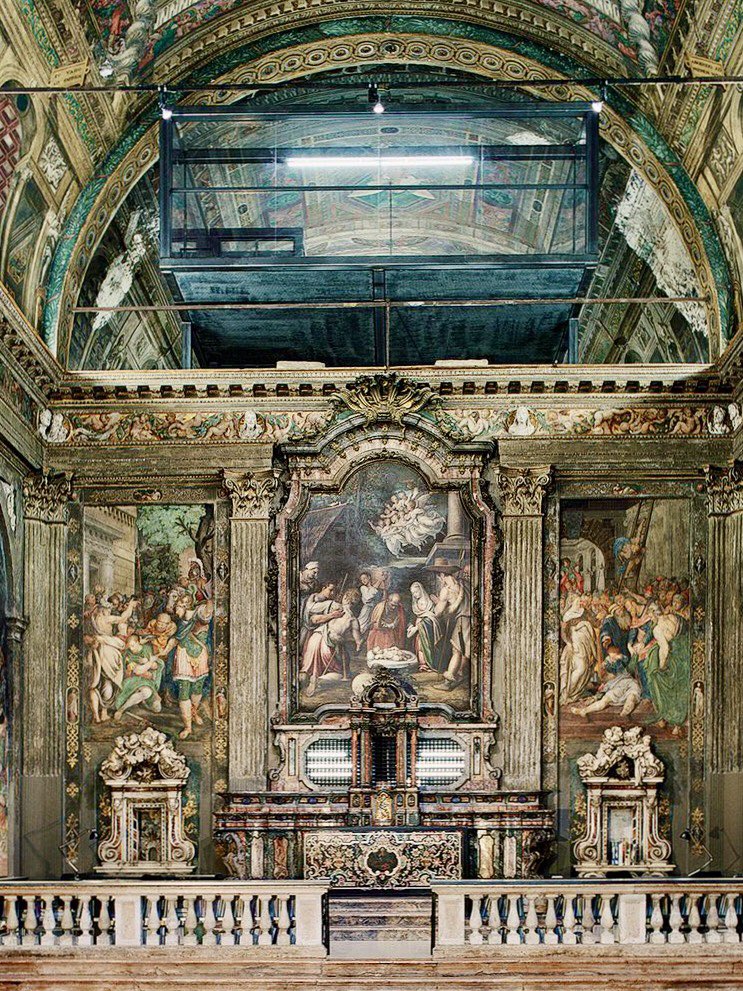

At times, amidst the splendor of the Vatican and the power of the papacy, which remains the center of Christianity and billions of faithful, he almost appeared uncomfortable with his role

At times, amidst the splendor of the Vatican and the power of the papacy, which remains the center of Christianity and billions of faithful, he almost appeared uncomfortable with his role

In this video, the man who would become his successor, and who, respectfully, would take his name as Pope John Paul II, is seen as Cardinal Karol Wojtyła, throwing himself at his feet and embracing him, unaware of what would happen in less than two months

Albino Luciani was beatified by Pope Francis on September 4, 2022, after a miracle was attributed to him

This remains a sad story, shrouded in shadows

Why would someone want him dead?

Luciani’s short papacy unsettled powerful interests:

Why would someone want him dead?

Luciani’s short papacy unsettled powerful interests:

1.Vatican Bank – He was probing Banco Ambrosiano, tied to Freemasons, the Mafia, and possibly the CIA

2.Shake-Up Plans – He aimed to remove key conservatives, including Secretary of State Jean Villot, who later managed his death with unusual haste

Thank you for reading this far

After all, the conclave’s identifying phrase is “extra omnes”, which means “everyone out”, because no one truly knows what happens inside the Sistine Chapel

After all, the conclave’s identifying phrase is “extra omnes”, which means “everyone out”, because no one truly knows what happens inside the Sistine Chapel

Ah, postscript—just know that if anything happens to me after this thread, I am not, and never will be, a suici$al personality 😉

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh