The Sistine Chapel is one of the world's greatest buildings, and it has the most famous ceiling in history.

But what is it, who built it, and what does "Sistine" even mean?

Well, here's the surprisingly controversial history of the Sistine Chapel...

But what is it, who built it, and what does "Sistine" even mean?

Well, here's the surprisingly controversial history of the Sistine Chapel...

Where did the Sistine Chapel get its name?

It was commissioned in 1473 by Pope Sixtus IV and completed nine years later.

His name in Italian was Sisto and the chapel was named after him, hence "Sistine" Chapel.

It was commissioned in 1473 by Pope Sixtus IV and completed nine years later.

His name in Italian was Sisto and the chapel was named after him, hence "Sistine" Chapel.

Where is the Sistine Chapel?

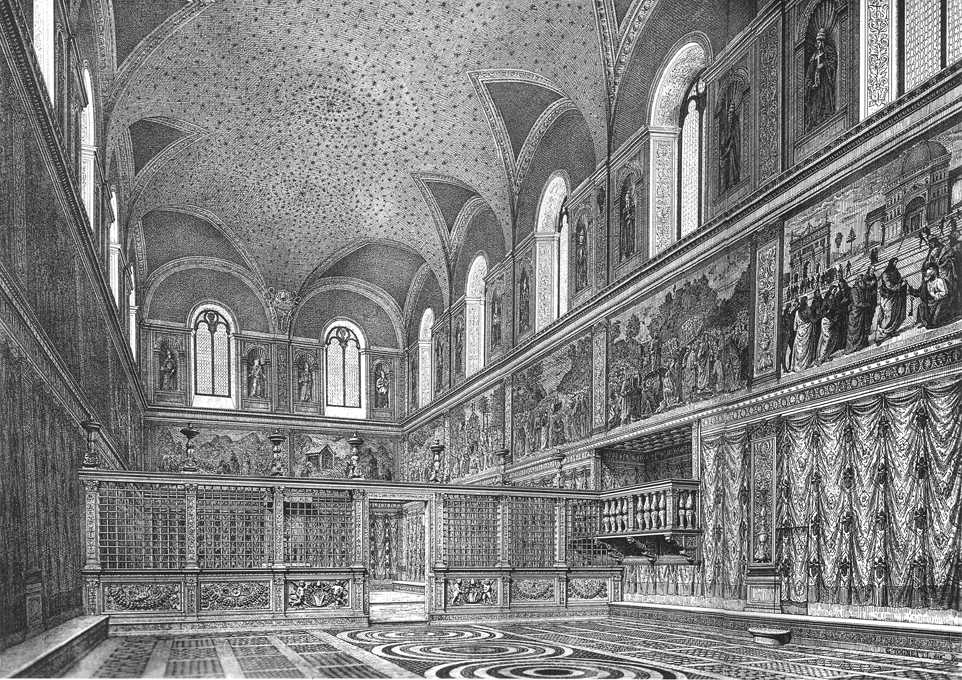

It's within the Apostolic Palace — the Pope's official residence — in the Vatican City.

But, for such a famous and important building, it isn't very noteworthy or impressive from the outside.

It's within the Apostolic Palace — the Pope's official residence — in the Vatican City.

But, for such a famous and important building, it isn't very noteworthy or impressive from the outside.

After Sixtus' chapel was completed he had it decorated by the leading artists of the day, such as Botticelli, Ghirlandaio, and Perugino.

Everybody looks up — but along the walls of the Sistine Chapel are some of the other great works of the Italian Renaissance.

Everybody looks up — but along the walls of the Sistine Chapel are some of the other great works of the Italian Renaissance.

Well, their fame has been eclipsed by Michelangelo's ceiling.

By his early thirties Michelangelo had become the greatest sculptor in Italy, having already made the Pieta and David.

But he wasn't much of a painter — it was marble that Michelangelo loved most.

By his early thirties Michelangelo had become the greatest sculptor in Italy, having already made the Pieta and David.

But he wasn't much of a painter — it was marble that Michelangelo loved most.

Enter Pope Julius II, nephew of Sixtus IV, known as the "warrior pope" — his papal name was inspired by Julius Caesar.

This portrait of him by Raphael seems to show a pious old man... but it actually depicts Julius in mourning over the loss of Bologna in war.

This portrait of him by Raphael seems to show a pious old man... but it actually depicts Julius in mourning over the loss of Bologna in war.

Julius may have been a warmonger, but he was also a patron of the arts — perhaps because he wanted his name to be remembered forever.

So in 1508 he commissioned Michelangelo, then 33, to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

His fee was equivalent to about $500,000 dollars.

So in 1508 he commissioned Michelangelo, then 33, to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

His fee was equivalent to about $500,000 dollars.

Michelangelo started work in 1508 — it would take him four years to finish.

The ceiling had originally been painted like the night sky, with stars over a blue background.

This was removed for Michelangelo, who painted on freshly laid plaster each day.

The ceiling had originally been painted like the night sky, with stars over a blue background.

This was removed for Michelangelo, who painted on freshly laid plaster each day.

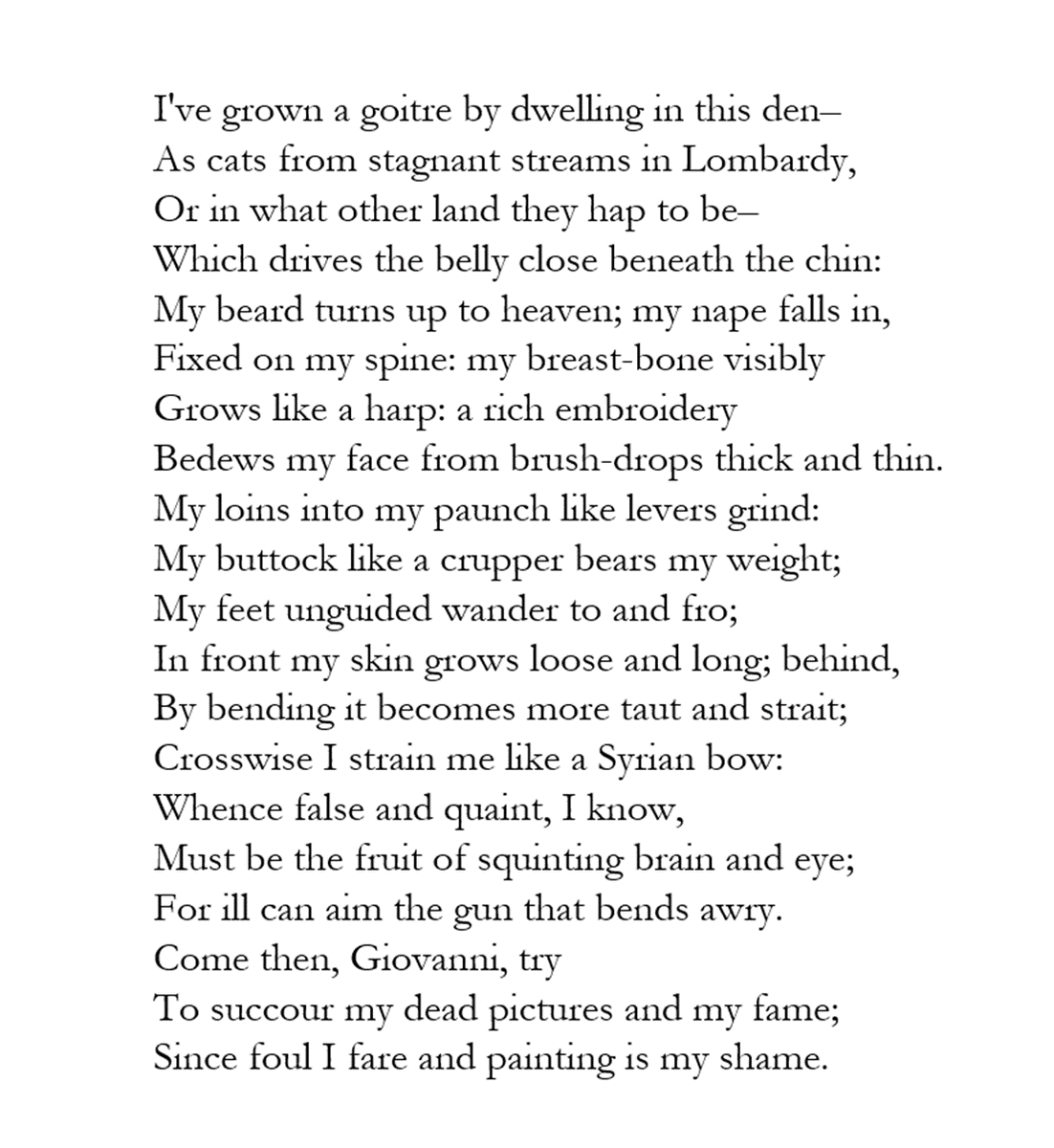

Popular myth says Michelangelo painted the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel laying on his back, but the truth is that he painted it standing, bent over backwards on a special raised scaffold.

He had back problems for the rest of his life — and even wrote a poem about it:

He had back problems for the rest of his life — and even wrote a poem about it:

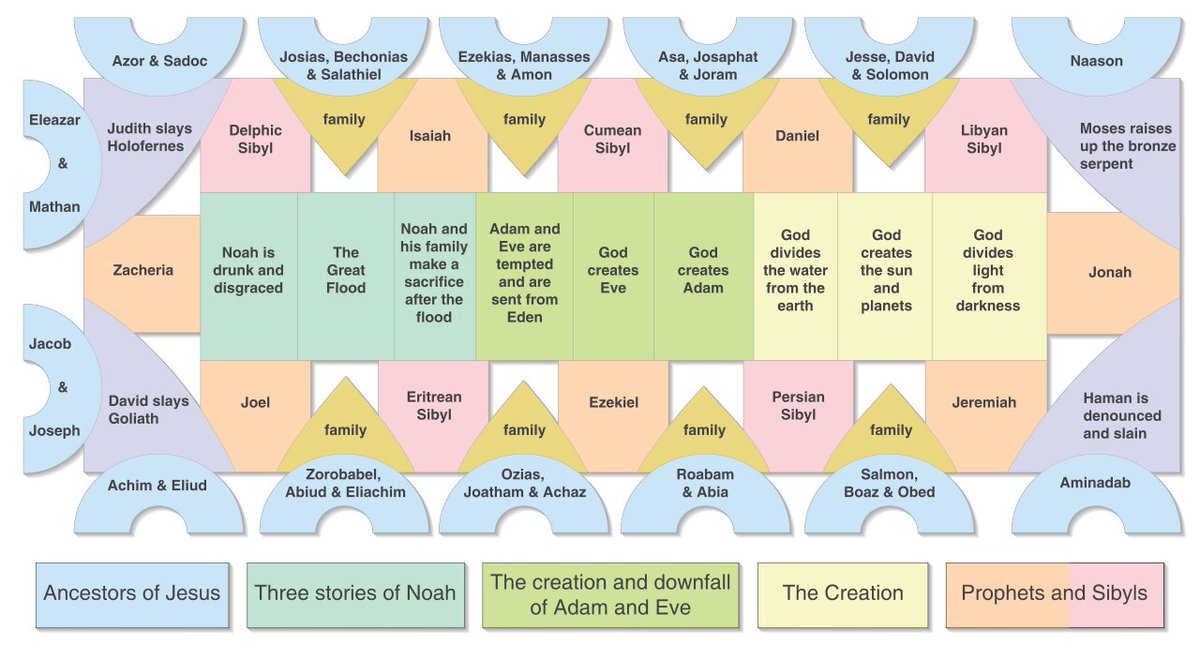

This is the overall plan of Michelangelo's ceiling.

A complex array of stories from the Old Testament, especially from Genesis, and of prophets and other biblical scenes, along with a motley crew of angels, cherubs, and more.

A totality of scripture made visible in art.

A complex array of stories from the Old Testament, especially from Genesis, and of prophets and other biblical scenes, along with a motley crew of angels, cherubs, and more.

A totality of scripture made visible in art.

So there's a lot going on here — there are more than three hundred figures in all.

And it's a supreme example of illusionistic art: the surface of the ceiling is smooth, but Michelangelo organised his figures among painted architectural details to create depth and order.

And it's a supreme example of illusionistic art: the surface of the ceiling is smooth, but Michelangelo organised his figures among painted architectural details to create depth and order.

The most famous parts are those he painted last.

He started with the minor scenes because he wanted to perfect his technique before attempting to paint God — it's easy to forget that Michelangelo was literally learning on the job.

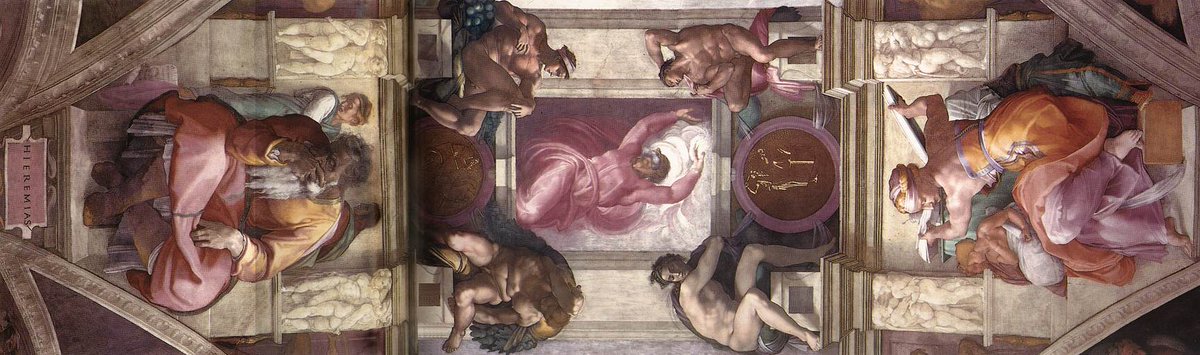

Here God divides the light from the darkness:

He started with the minor scenes because he wanted to perfect his technique before attempting to paint God — it's easy to forget that Michelangelo was literally learning on the job.

Here God divides the light from the darkness:

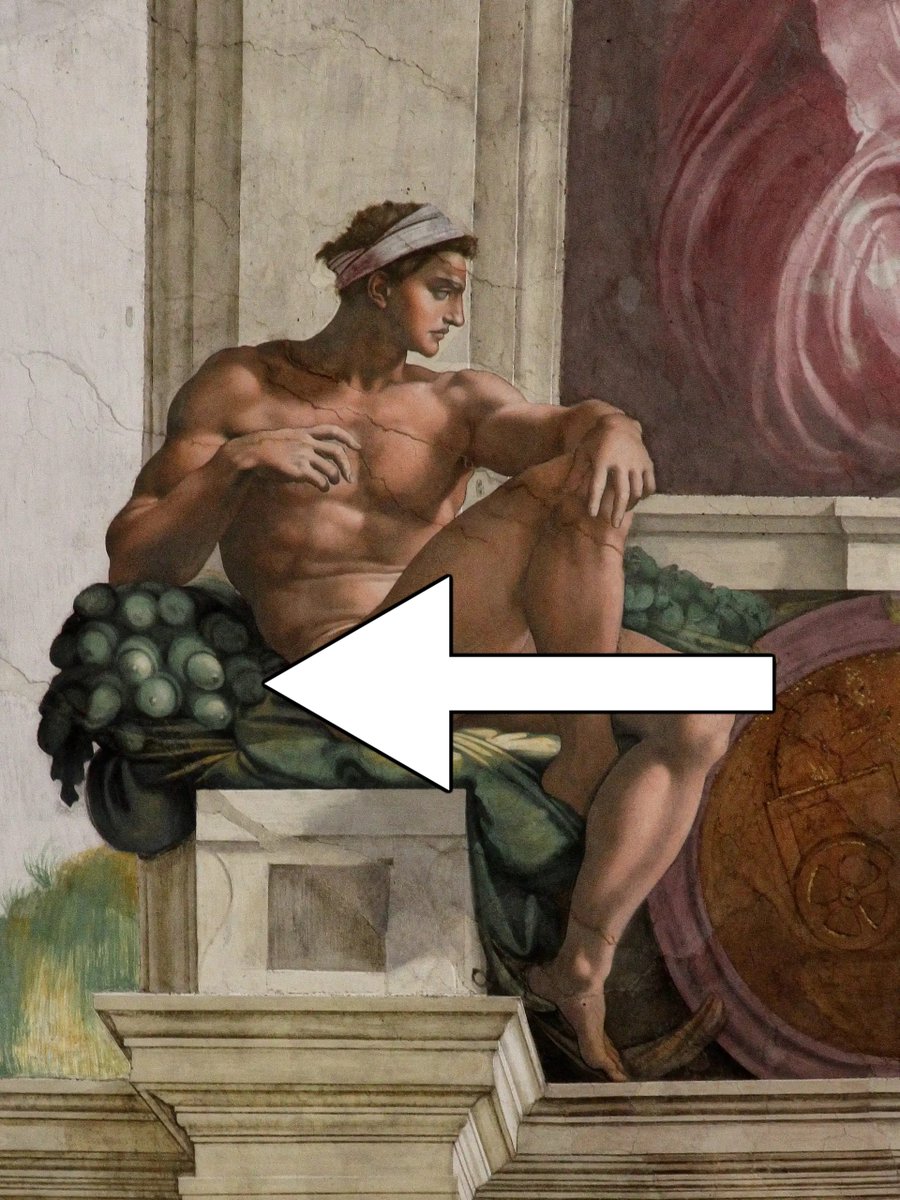

The ceiling of the Sistine Chapel is also, curiously, filled with acorns.

Why? Julius II was born Giuliano della Rovere, and Rovere means oak in Italian.

Hence his personal symbol was the acorn, and Michelangelo's inclusion of them was a symbol of his patronage.

Why? Julius II was born Giuliano della Rovere, and Rovere means oak in Italian.

Hence his personal symbol was the acorn, and Michelangelo's inclusion of them was a symbol of his patronage.

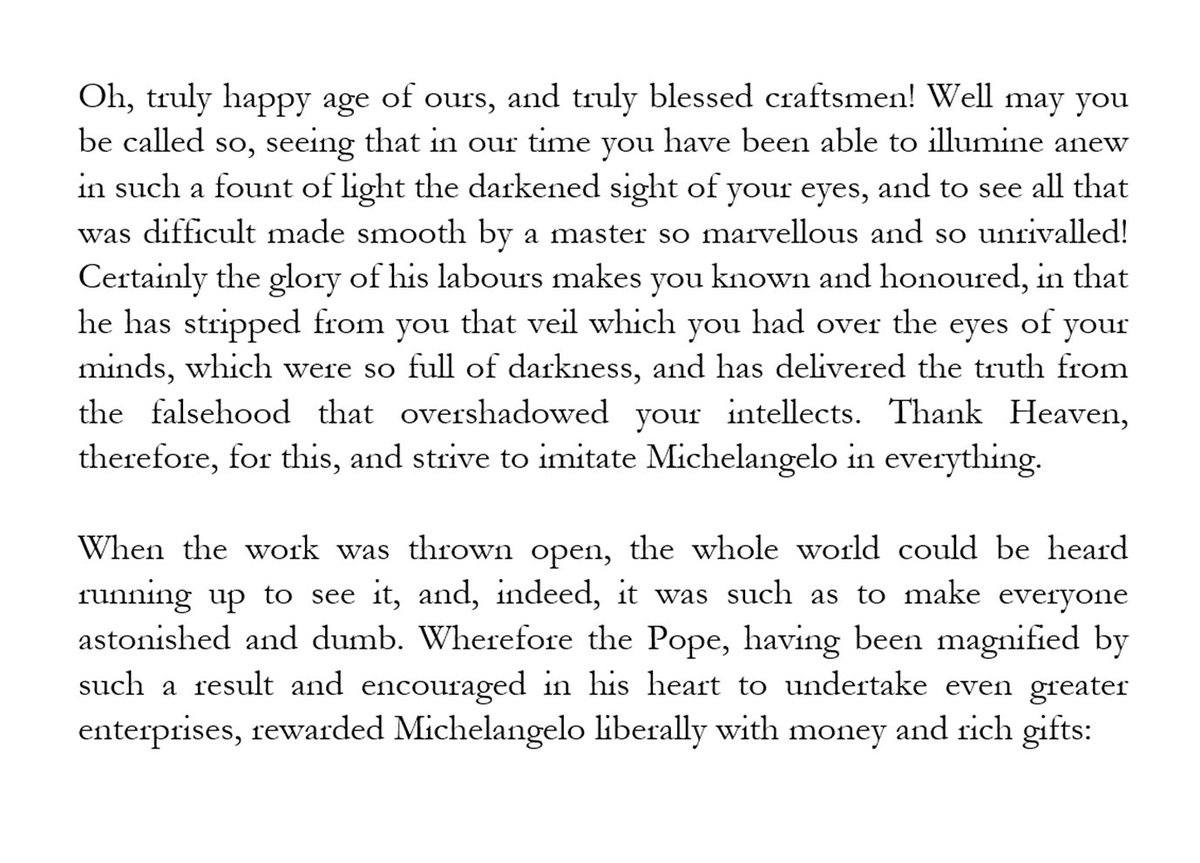

Four years passed, Michelangelo completed his project, and the ceiling was unveiled in November 1512.

It was immediately hailed as a masterpiece and Michelangelo as the greatest artist of all time.

As the biographer Giorgio Vasari said only a few years later:

It was immediately hailed as a masterpiece and Michelangelo as the greatest artist of all time.

As the biographer Giorgio Vasari said only a few years later:

But Michelangelo was a controversial artist whose works inevitably divided people.

Most startling of all was his decision to include five "sibyls" — oracles from the ancient world of Greece, Rome, and Persia.

Mixing pagan and Christian figures was, at the time, shocking.

Most startling of all was his decision to include five "sibyls" — oracles from the ancient world of Greece, Rome, and Persia.

Mixing pagan and Christian figures was, at the time, shocking.

Others were appalled by the amount of nudity.

But Michelangelo, true to the Renaissance and its revival of ancient art, was inspired by the heroic nude statues of Ancient Greece and Rome.

Hence the muscular torsos and twisting bodies which defined his painting and sculpture.

But Michelangelo, true to the Renaissance and its revival of ancient art, was inspired by the heroic nude statues of Ancient Greece and Rome.

Hence the muscular torsos and twisting bodies which defined his painting and sculpture.

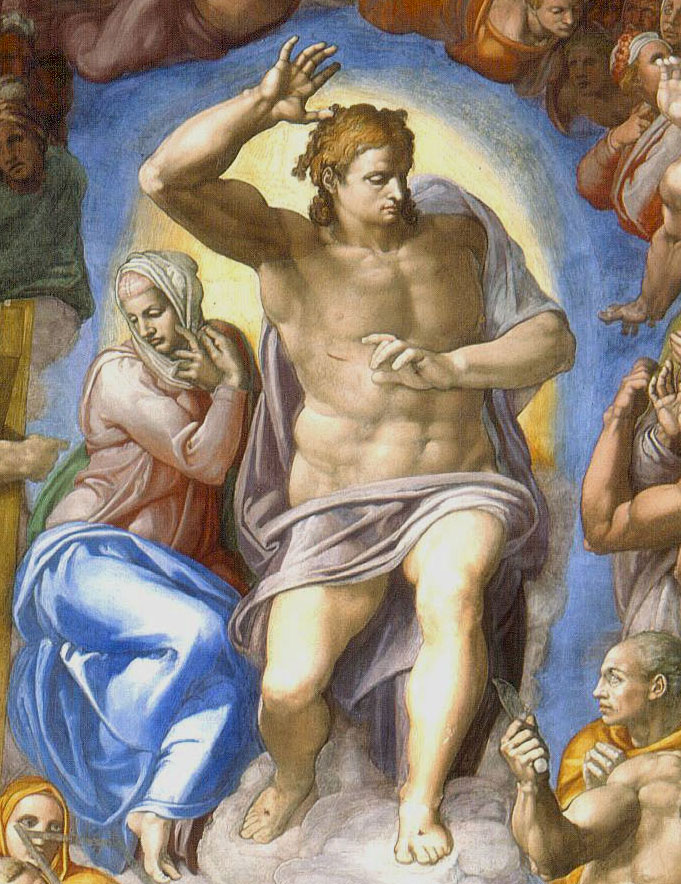

Twenty year later, in 1535, Michelangelo was invited back to the Sistine Chapel by Pope Paul III.

This time he was asked to paint the last judgment on its altar wall.

Michelangelo had the wall adjusted — so that its top sticks out further than the bottom — and got to work.

This time he was asked to paint the last judgment on its altar wall.

Michelangelo had the wall adjusted — so that its top sticks out further than the bottom — and got to work.

Over the next six years he broke radically from traditional depictions of the last judgment.

His version was far more complex, he didn't paint Jesus on a throne, he didn't arrange the angels or resurrected as described in the Bible, and he included figures from Greek mythology.

His version was far more complex, he didn't paint Jesus on a throne, he didn't arrange the angels or resurrected as described in the Bible, and he included figures from Greek mythology.

Jesus hadn't been portrayed beardless for centuries (which was controversial in itself), not to mention that his muscular body makes him look more like a Greek god.

This was highly unorthodox and widely criticised, but Michelangelo the aging master was a law unto himself.

This was highly unorthodox and widely criticised, but Michelangelo the aging master was a law unto himself.

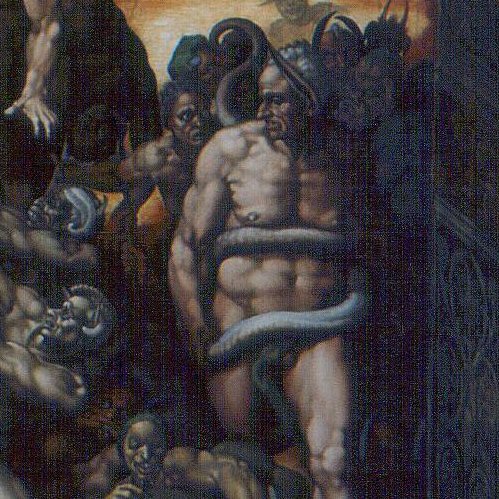

And so, even before it was finished, The Last Judgment became controversial.

Its departure from scripture, its complex composition, its profusion of violently contorted bodies... as Vasari writes, this was too much for some, especially in a place like the Sistine Chapel:

Its departure from scripture, its complex composition, its profusion of violently contorted bodies... as Vasari writes, this was too much for some, especially in a place like the Sistine Chapel:

Michelangelo's portrayal of Biagio da Cesena remains: as Minos, judge of the underworld, enwrapped by a serpent.

Here we see Michelangelo's ruthless and uncompromising personality in full — he used the Sistine Chapel, ostensibly a holy place, to get revenge on his critics.

Here we see Michelangelo's ruthless and uncompromising personality in full — he used the Sistine Chapel, ostensibly a holy place, to get revenge on his critics.

In the end Michelangelo's non-scriptural Last Judgement, a wall of three hundred confusingly arranged naked bodies, was just too much.

So after his death, in 1564, Michelangelo's former pupil Daniele da Volterra was hired to paint loincloths over the nude figures.

So after his death, in 1564, Michelangelo's former pupil Daniele da Volterra was hired to paint loincloths over the nude figures.

The Sistine Chapel was used continuously for five centuries, whether for religious services or for the conclave that gathers to elect the new pope.

And so by the 20th century its ceiling had deteriorated, with the paintings covered in soot and grime.

And so by the 20th century its ceiling had deteriorated, with the paintings covered in soot and grime.

In the 1980s there was a major restoration.

All filth and the remains of previous restorations were removed in an attempt to restore Michelangelo's original work.

From beneath the soot emerged a far brighter ceiling, but some argued that Michelangelo's subtleties had been lost.

All filth and the remains of previous restorations were removed in an attempt to restore Michelangelo's original work.

From beneath the soot emerged a far brighter ceiling, but some argued that Michelangelo's subtleties had been lost.

And that's a brief history of the Sistine Chapel, filled with some of the most influential and controversial art ever made.

Perhaps it should even be called Michelangelo's Chapel — after all, it his radical art and his unusual personality that have come to define the place.

Perhaps it should even be called Michelangelo's Chapel — after all, it his radical art and his unusual personality that have come to define the place.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh