“Holy Spirits”

The menu from Pope Leo XIV’s first dinner with the cardinals has surfaced

A Thread 🧵 on the excellent Italian wines chosen for the occasion 🥂

The menu from Pope Leo XIV’s first dinner with the cardinals has surfaced

A Thread 🧵 on the excellent Italian wines chosen for the occasion 🥂

After the intense days of the conclave, on the evening of May 8th, a beautiful dinner was offered at Santa Marta to all the cardinals who had taken part in the election — a moment to celebrate the Habemus Papam and the beginning of the pontificate of Leo XIV ✨

But beyond the five rather international courses served to the cardinals, let’s focus for a moment on what they were given to drink 🥂

White wine

A Vermentino from Tenuta Guado al Tasso, crafted by the Italian 🇮🇹legendary Antinori family

A Vermentino from Tenuta Guado al Tasso, crafted by the Italian 🇮🇹legendary Antinori family

Guado al Tasso Vermentino is a premium white wine produced by Marchesi Antinori in Bolgheri, Tuscany

Made from 100% Vermentino, this Mediterranean grape is celebrated for its bright acidity, floral notes, and vibrant aromatic profile

Elegant, crisp, and quite complex

Made from 100% Vermentino, this Mediterranean grape is celebrated for its bright acidity, floral notes, and vibrant aromatic profile

Elegant, crisp, and quite complex

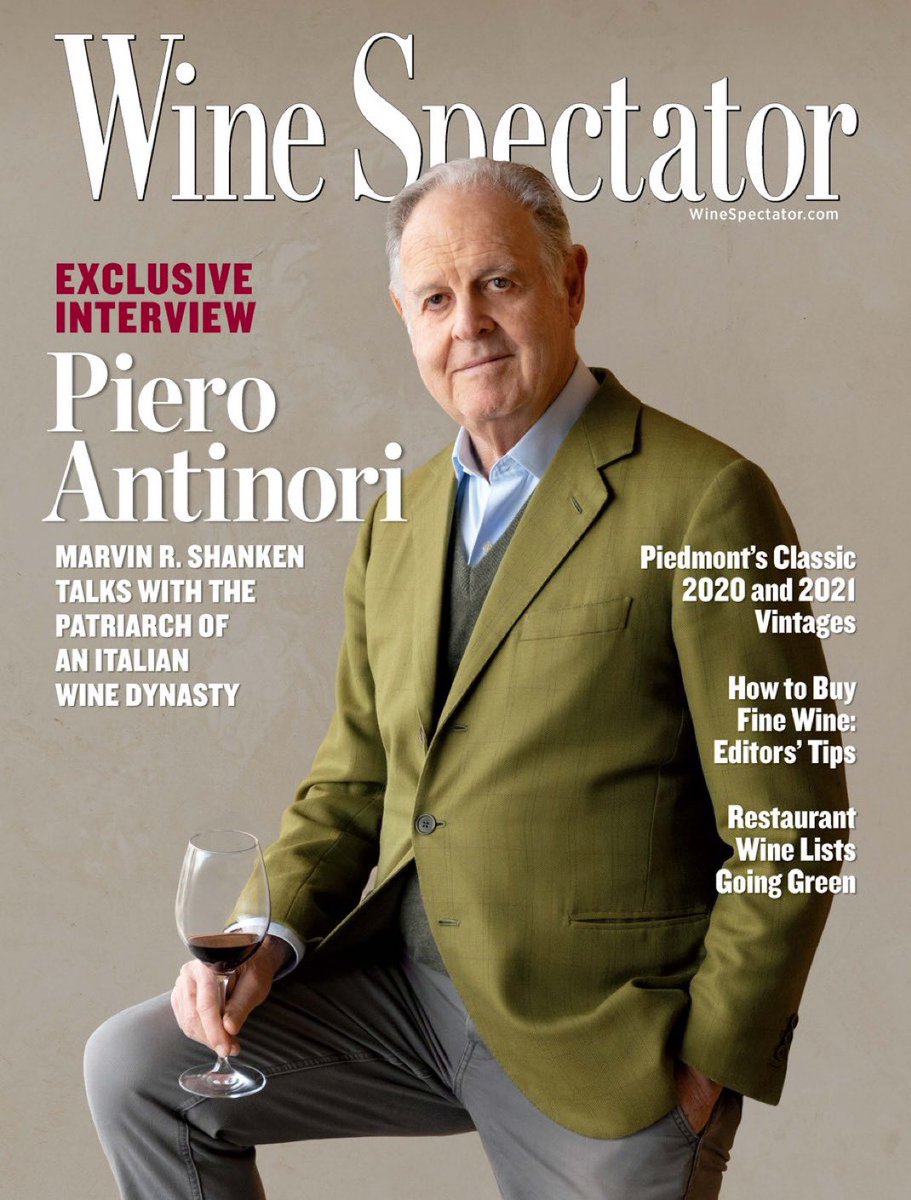

For those who want to dig a little deeper: the Marchesi Antinori are perhaps the most renowned wine-producing family in Italy 🇮🇹

Wine Spectator has celebrated this “Tuscan aristocrat”, the 25th generation of the Antinori dynasty, as one of the greatest visionaries in Italian wine

What began as a wine trading activity back in 1385 has become a global powerhouse, with over 2,800 hectares of vineyards

What began as a wine trading activity back in 1385 has become a global powerhouse, with over 2,800 hectares of vineyards

Among their most celebrated creations is the incredible Tignanello — widely considered one of the finest, most famous, and internationally acclaimed Italian wines

Just south of Florence lies one of their main estates, which is open to visitors

I’ve personally been there, Antinori Chianti Classico, and it’s truly extraordinary

Beautifully integrated into the surrounding landscape, it’s an unforgettable experience that I 100% recommend 🍷

I’ve personally been there, Antinori Chianti Classico, and it’s truly extraordinary

Beautifully integrated into the surrounding landscape, it’s an unforgettable experience that I 100% recommend 🍷

But let’s get back to the Pope’s dinner with the cardinals

The red wine served was a Ripasso della Valpolicella from Cantina Aldegheri

The bottle in the photo shows a 2018 vintage, but the one actually poured was from 2023 — a truly excellent red wine 🍷

The red wine served was a Ripasso della Valpolicella from Cantina Aldegheri

The bottle in the photo shows a 2018 vintage, but the one actually poured was from 2023 — a truly excellent red wine 🍷

The red comes from Valpolicella, a beautiful, small region in Veneto (Italy 🇮🇹) known for its exceptional vineyards

It’s the land of two iconic wines

The famous Amarone and the Ripasso, the one served to the Pope and the cardinals

It’s the land of two iconic wines

The famous Amarone and the Ripasso, the one served to the Pope and the cardinals

Ripasso della Valpolicella is a smooth, full-flavored red

Made by fermenting over Amarone grape skins, it gains richness and depth

Expect notes of ripe cherry, plum, spice, and a soft touch of sweetness

Elegant, well-balanced, and perfect with hearty dishes or aged cheese

Made by fermenting over Amarone grape skins, it gains richness and depth

Expect notes of ripe cherry, plum, spice, and a soft touch of sweetness

Elegant, well-balanced, and perfect with hearty dishes or aged cheese

Cantina Aldegheri:

The winery chosen for the red wine, is quite different from Antinori

It’s a family-run, much younger winery, dynamic and focused on producing wines of the highest quality, all while respecting the excellence of the local terroir

The winery chosen for the red wine, is quite different from Antinori

It’s a family-run, much younger winery, dynamic and focused on producing wines of the highest quality, all while respecting the excellence of the local terroir

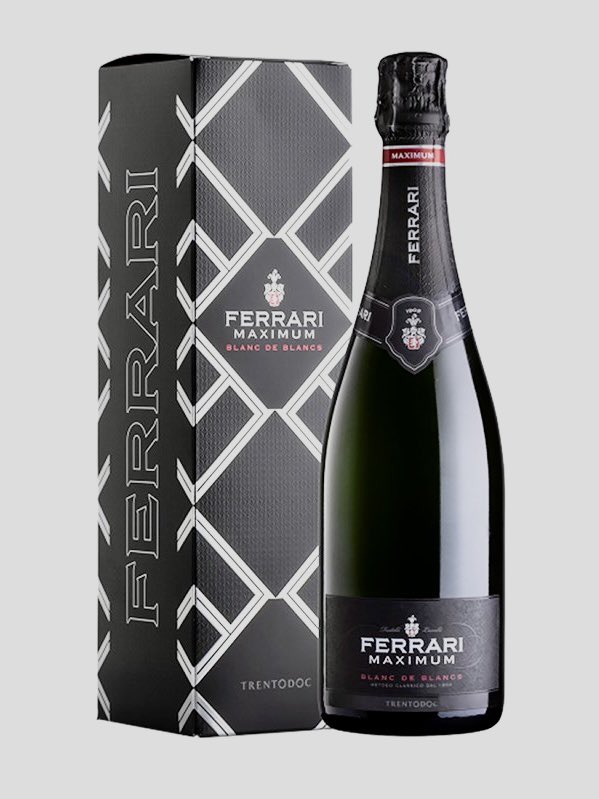

Now, for the toast to the new Pope: a classic and thoroughly Italian Blanc de Blancs Ferrari

A Trentodoc, absolutely perfect for toasts and celebrations, with exceptional bubbles

A Trentodoc, absolutely perfect for toasts and celebrations, with exceptional bubbles

Ferrari Spumante is a well-known Italian brand — sharing its name with the famous cars, though unrelated

Founded in Trento in 1902, it has been one of the world’s leading producers of classic method sparkling wines for over a century

A true symbol of Italian excellence

Founded in Trento in 1902, it has been one of the world’s leading producers of classic method sparkling wines for over a century

A true symbol of Italian excellence

Ferrari Blanc de Blancs Trentodoc is made from 100% Chardonnay and aged 30 months on the lees

It features fine bubbles, fresh citrus and apple notes, with hints of brioche and almond

Elegant, crisp, and beautifully balanced, a standout Italian sparkling wine 🥂

It features fine bubbles, fresh citrus and apple notes, with hints of brioche and almond

Elegant, crisp, and beautifully balanced, a standout Italian sparkling wine 🥂

I hope you enjoyed this short thread since it includes three great wine suggestions, all of excellent Italian quality and at accessible prices

And with that, let’s take this moment to raise a glass and send our warmest wishes for a long and wonderful pontificate to Pope Leo XIV!

And with that, let’s take this moment to raise a glass and send our warmest wishes for a long and wonderful pontificate to Pope Leo XIV!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh