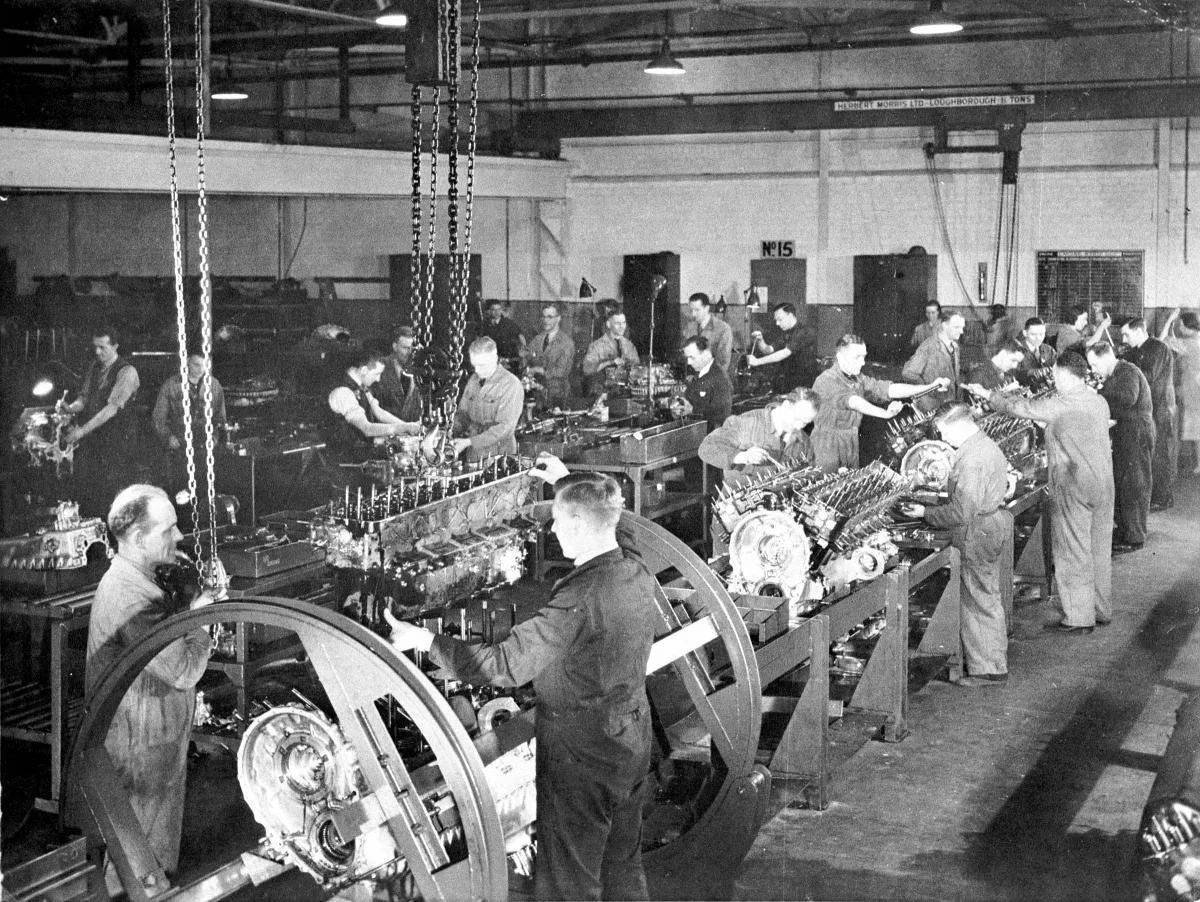

Karl Marx said he had discovered the scientific laws of economics.

Value came from labor.

Profit was theft.

Only central planning could build a just society.

But four Austrian economists—Menger, Böhm-Bawerk, Mises, and Hayek—tore his theory apart. 🧵

Value came from labor.

Profit was theft.

Only central planning could build a just society.

But four Austrian economists—Menger, Böhm-Bawerk, Mises, and Hayek—tore his theory apart. 🧵

Marx said value comes from labor.

Carl Menger said: value comes from us.

In Principles of Economics (1871), he showed that value is subjective. It depends on the preferences of individuals—changing across people, places, and time.

A violin is priceless to a musician, worthless to someone else. Food is worth more to the starving than to the full.

Labor doesn’t determine value.

Human needs do.

Carl Menger said: value comes from us.

In Principles of Economics (1871), he showed that value is subjective. It depends on the preferences of individuals—changing across people, places, and time.

A violin is priceless to a musician, worthless to someone else. Food is worth more to the starving than to the full.

Labor doesn’t determine value.

Human needs do.

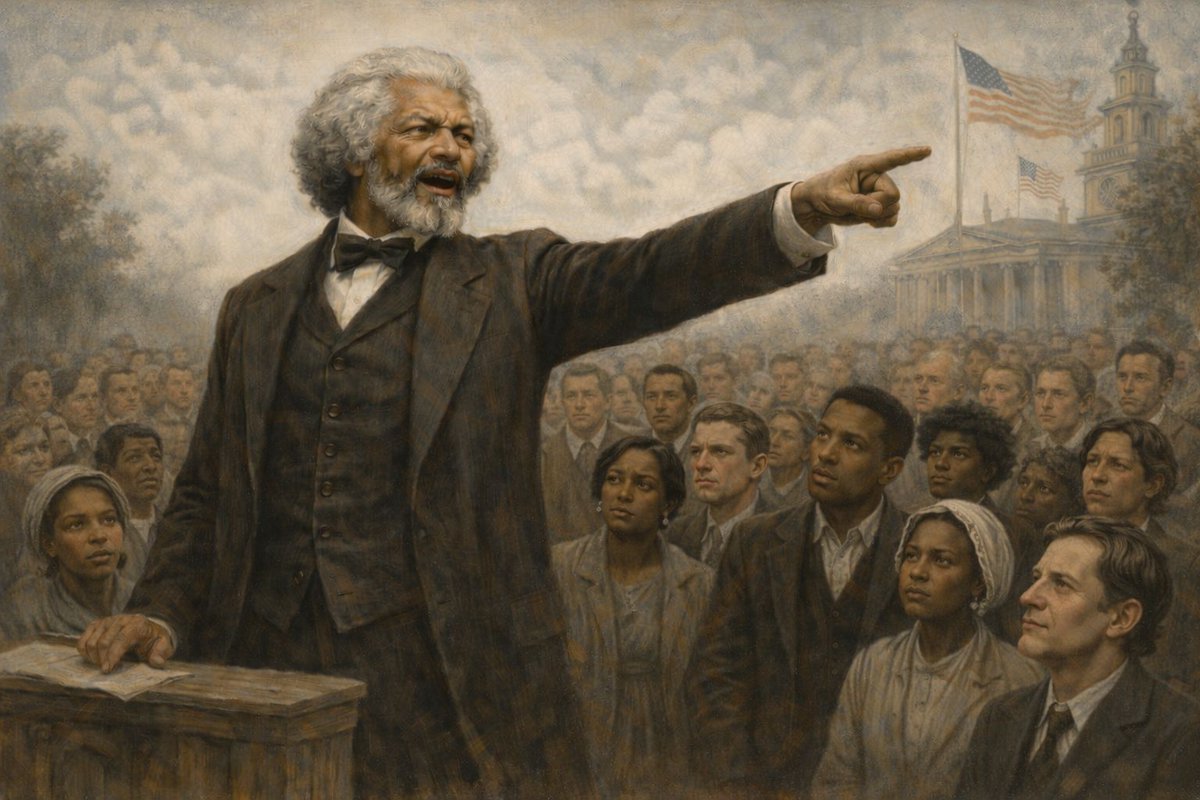

Marx said capitalists exploit workers.

Eugen Böhm-Bawerk introduced a different explanation: time preference.

Workers value present income. Capitalists provide that income now in exchange for uncertain profits later.

They take the risk, front the capital, and hope it pays off.

Profit is not exploitation. It’s compensation for time, risk, and planning.

Eugen Böhm-Bawerk introduced a different explanation: time preference.

Workers value present income. Capitalists provide that income now in exchange for uncertain profits later.

They take the risk, front the capital, and hope it pays off.

Profit is not exploitation. It’s compensation for time, risk, and planning.

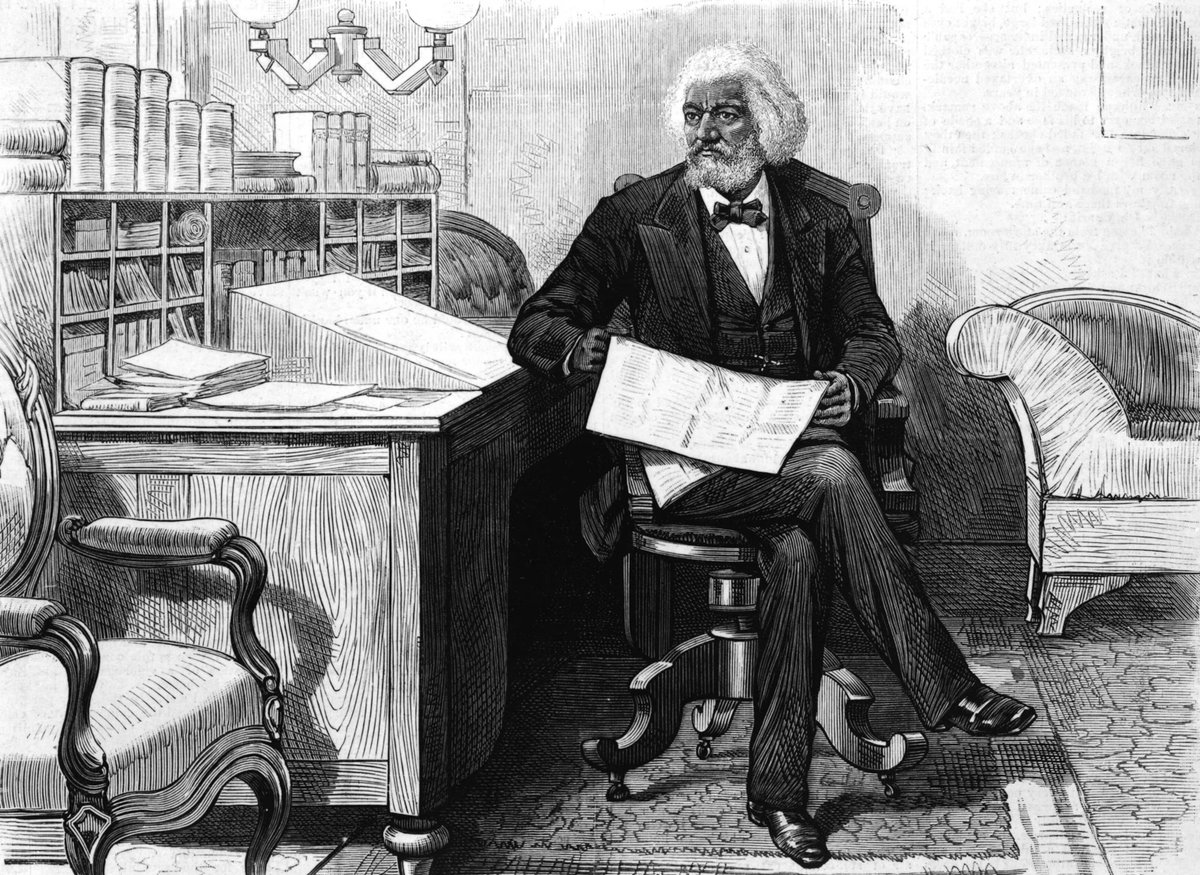

But what if we abolished capitalism?

How would the state know what to produce?

Ludwig von Mises asked this in 1920—and proved socialism couldn’t answer it.

Without prices, there’s no way to compare costs or plan tradeoffs.

No real prices = no real economy.

He didn’t say socialism lacked morality.

He said it lacked logic.

How would the state know what to produce?

Ludwig von Mises asked this in 1920—and proved socialism couldn’t answer it.

Without prices, there’s no way to compare costs or plan tradeoffs.

No real prices = no real economy.

He didn’t say socialism lacked morality.

He said it lacked logic.

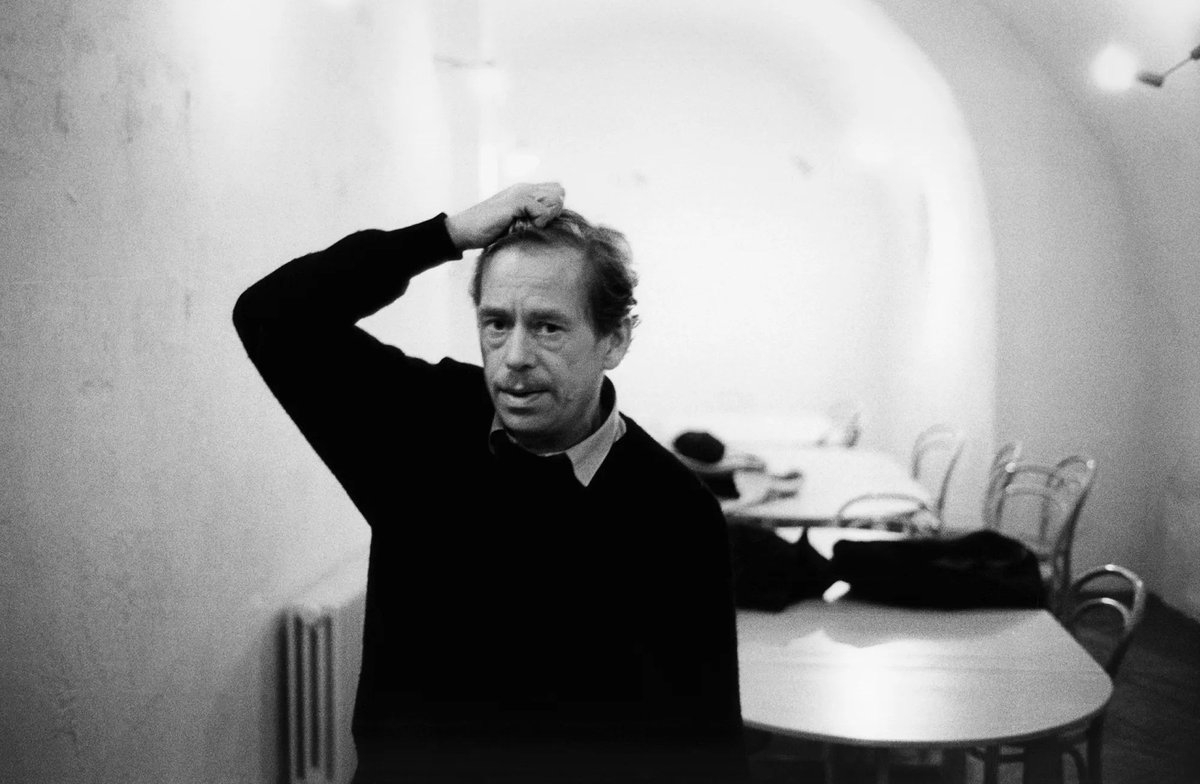

F.A. Hayek went further.

He argued that no central planner could match the knowledge spread across society.

Prices aren’t just numbers. They’re signals—reflecting local needs, priorities, and scarcities.

Prices reflect that knowledge. They allow individuals to coordinate without any central planner needing to understand the full picture.

No expert, no algorithm, no five-year plan can replace that.

He argued that no central planner could match the knowledge spread across society.

Prices aren’t just numbers. They’re signals—reflecting local needs, priorities, and scarcities.

Prices reflect that knowledge. They allow individuals to coordinate without any central planner needing to understand the full picture.

No expert, no algorithm, no five-year plan can replace that.

By the mid-20th century, Marxist economics had collapsed.

Menger refuted the labor theory of value.

Böhm-Bawerk dismantled surplus value.

Mises exposed the limits of planning.

Hayek explained why decentralization matters.

The Austrians didn’t just critique Marx. They offered a more coherent framework—rooted in individual choice, not class struggle.

Menger refuted the labor theory of value.

Böhm-Bawerk dismantled surplus value.

Mises exposed the limits of planning.

Hayek explained why decentralization matters.

The Austrians didn’t just critique Marx. They offered a more coherent framework—rooted in individual choice, not class struggle.

So why does it matter now?

Because Marx’s bad ideas never die.

Price controls.

Central planning.

The constant vilification of profit.

Every time we forget what crushed Marxism, it crawls back—under new slogans, with old consequences.

Because Marx’s bad ideas never die.

Price controls.

Central planning.

The constant vilification of profit.

Every time we forget what crushed Marxism, it crawls back—under new slogans, with old consequences.

Most students never learn this story.

They don’t know how Marx fell.

They don’t know why the Austrians won.

And they don’t realize how many of today’s bad ideas echo the same fallacies—just with friendlier branding.

They don’t know how Marx fell.

They don’t know why the Austrians won.

And they don’t realize how many of today’s bad ideas echo the same fallacies—just with friendlier branding.

Want to go deeper?

We made a short, free email course called How to Not Be an NPC on Tariffs.

Inside, you’ll learn:

– Why tariffs are about power, not just trade

– Who wins, who loses—and why

– What economists don’t say on cable news

– How these debates still shape our world

Start here → go.studentsforliberty.org/learn-tariffs/

We made a short, free email course called How to Not Be an NPC on Tariffs.

Inside, you’ll learn:

– Why tariffs are about power, not just trade

– Who wins, who loses—and why

– What economists don’t say on cable news

– How these debates still shape our world

Start here → go.studentsforliberty.org/learn-tariffs/

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh