No helmet. Just gum, guts, and greatness.

Presenting the deepest dive into Sir Viv Richards' story

A thread worth every scroll. 🧵👇

Presenting the deepest dive into Sir Viv Richards' story

A thread worth every scroll. 🧵👇

St. John’s, Antigua, 1952. Viv Richards was born into a home where cricket wasn’t just a game; it was part of the bloodline. His father, Malcolm, was a fast bowler with a fierce run-up. His brothers, Donald and Mervyn, played for local teams. The backyard was their stadium.

Viv didn’t have a proper bat. He didn’t need one. He picked up a coconut branch, wrapped tape around a tennis ball, and taught himself timing, reflexes, and power. One of his early coaches once said, “There’s fire in his wrists.” He wasn’t wrong.

Viv looked up to Sir Garfield Sobers. but he dreamed bigger. He wanted to be the greatest.

Not just for Antigua. Not just for the West Indies.

For the world.

Viv didn’t have a proper bat. He didn’t need one. He picked up a coconut branch, wrapped tape around a tennis ball, and taught himself timing, reflexes, and power. One of his early coaches once said, “There’s fire in his wrists.” He wasn’t wrong.

Viv looked up to Sir Garfield Sobers. but he dreamed bigger. He wanted to be the greatest.

Not just for Antigua. Not just for the West Indies.

For the world.

At 18, Viv Richards walked away from school with no plan but a heart full of fire. He took up a job at D’Arcy’s Bar and Restaurant in St. John’s, Antigua. It was a small job but it paid. The owner, D’Arcy Williams, saw something else in the young man. Maybe it was the way Viv talked about cricket. One day, Williams gave him a full set of cricket gear.

With that kit, Viv joined the St. John’s Cricket Club. Soon after, he moved to the Rising Sun Cricket Club. There, his game grew. People started noticing the boy who didn’t flinch.

In 1973, a tour brought Somerset County Cricket Club to the Caribbean. Their vice-chairman, Len Creed, watched a young batsman tear into their bowling. There was something magnetic about him. Creed didn’t waste time. He offered Viv a chance to come to England.

Viv took it. He landed in Bath and started playing for Lansdown Cricket Club. He worked as an assistant groundsman, earning just £1 a day. He’d mow the outfield in the morning and take guard on it in the afternoon. He wasn’t complaining. He was learning.

It didn’t take long. Somerset gave him a county contract. In 1974, he debuted for the team and shared a flat with Ian Botham and Dennis Breakwell. Three young men with nothing to lose. They didn’t just play cricket. They lived it. That house became a factory for ambition.

In one match, he fractured his toe early in the innings. He didn’t tell anyone. He just tightened his boot and batted on. Limping between the wickets, smashing bowlers like nothing was wrong.

With that kit, Viv joined the St. John’s Cricket Club. Soon after, he moved to the Rising Sun Cricket Club. There, his game grew. People started noticing the boy who didn’t flinch.

In 1973, a tour brought Somerset County Cricket Club to the Caribbean. Their vice-chairman, Len Creed, watched a young batsman tear into their bowling. There was something magnetic about him. Creed didn’t waste time. He offered Viv a chance to come to England.

Viv took it. He landed in Bath and started playing for Lansdown Cricket Club. He worked as an assistant groundsman, earning just £1 a day. He’d mow the outfield in the morning and take guard on it in the afternoon. He wasn’t complaining. He was learning.

It didn’t take long. Somerset gave him a county contract. In 1974, he debuted for the team and shared a flat with Ian Botham and Dennis Breakwell. Three young men with nothing to lose. They didn’t just play cricket. They lived it. That house became a factory for ambition.

In one match, he fractured his toe early in the innings. He didn’t tell anyone. He just tightened his boot and batted on. Limping between the wickets, smashing bowlers like nothing was wrong.

In November 1974, Viv Richards made his Test debut for the West Indies vs India. The numbers from his first match didn’t set the world on fire, but then came the 2nd Test in Delhi. Viv walked in and didn’t walk out until he had 192* runs to his name. It wasn’t just a century; it was a message. A few months later, the world gathered for the first-ever Cricket World Cup in 1975. In the final at Lord’s, Viv didn’t shine with the bat. But he lit up the field. Three direct-hit run-outs—Alan Turner, Greg Chappell, Ian Chappell. Each throw shifted the game.

Viv never wore a helmet, even against the fastest bowlers, Lillee, Thomson, and Holding. It wasn’t recklessness; it was psychological warfare. He chewed gum, stared bowlers down, and made swagger a weapon. Viv was famous for Chewing gum, he once reveled that how chewing gum helped him not to bother about wearing a helmet while batting. "Chewing gum also made me look cool, and wearing that mouthguard impeded my comfort zone. The chewing of gum helped take my mind away from stuff like not wearing that guard or even a helmet. I never wore a helmet when batting, and I never faced a bowler against whom I thought I should be wearing one."

Before every match, he’d find a corner in the dressing room. He’d sit alone, eyes shut, whispering to himself, “You’re the best. Now prove it.” His teammates heard it often. It wasn’t arrogance. It was belief. It was armor. At one formal West Indies team dinner, a guest asked Viv what he wanted out of cricket. He paused, smiled, and said, “To walk out there and make the world feel me. Whether I get a duck or a double hundred, they’ll know I was here.”

Viv never wore a helmet, even against the fastest bowlers, Lillee, Thomson, and Holding. It wasn’t recklessness; it was psychological warfare. He chewed gum, stared bowlers down, and made swagger a weapon. Viv was famous for Chewing gum, he once reveled that how chewing gum helped him not to bother about wearing a helmet while batting. "Chewing gum also made me look cool, and wearing that mouthguard impeded my comfort zone. The chewing of gum helped take my mind away from stuff like not wearing that guard or even a helmet. I never wore a helmet when batting, and I never faced a bowler against whom I thought I should be wearing one."

Before every match, he’d find a corner in the dressing room. He’d sit alone, eyes shut, whispering to himself, “You’re the best. Now prove it.” His teammates heard it often. It wasn’t arrogance. It was belief. It was armor. At one formal West Indies team dinner, a guest asked Viv what he wanted out of cricket. He paused, smiled, and said, “To walk out there and make the world feel me. Whether I get a duck or a double hundred, they’ll know I was here.”

Year 1976, It was supposed to be just another cricket tour. But one sentence changed everything. Before the Test series, England captain Tony Greig looked into a TV camera and said he would make the West Indies “grovel.” The word echoed with centuries of colonial weight. Across the Caribbean, it felt like a slap. Viv Richards was 24. He didn’t shout back. He just walked out with a bat and turned the series into a storm. In four Tests, Viv scored 829 runs at an average of 118.42. At The Oval, he played an innings of 291 runs, his highest ever. England couldn’t answer. The West Indies won 3–0. And Tony Greig? His “grovel” became a ghost that haunted him for years.

Later that summer, in an ODI at Old Trafford, West Indies were in deep trouble - 166 for 9. Viv was still there. He had walked in at No. 4, and he wasn’t leaving until he’d finished what he started. He scored an unbeaten 189 off 170 balls. No one else in the team crossed 30. He added 106 runs for the last wicket. Michael Holding stood at the other end and watched Viv take 93 of those. That record still stands, nobody has done it like that.

before or since. Then came the Australia tour. The crowds weren’t kind. One afternoon, the abuse turned racial. Viv didn’t react. He just waited. The next over, he hit three straight sixes into the section that had been mocking him. Then he turned, pointed his bat at them, and bowed.

That year, 1976, belonged to him. 11 Tests, 1,710 runs, an average of 90, 7 centuries, including two doubles. That record stood untouched for three decades.

Later that summer, in an ODI at Old Trafford, West Indies were in deep trouble - 166 for 9. Viv was still there. He had walked in at No. 4, and he wasn’t leaving until he’d finished what he started. He scored an unbeaten 189 off 170 balls. No one else in the team crossed 30. He added 106 runs for the last wicket. Michael Holding stood at the other end and watched Viv take 93 of those. That record still stands, nobody has done it like that.

before or since. Then came the Australia tour. The crowds weren’t kind. One afternoon, the abuse turned racial. Viv didn’t react. He just waited. The next over, he hit three straight sixes into the section that had been mocking him. Then he turned, pointed his bat at them, and bowed.

That year, 1976, belonged to him. 11 Tests, 1,710 runs, an average of 90, 7 centuries, including two doubles. That record stood untouched for three decades.

In 1979, the West Indies returned to Lord’s for the World Cup final, this time facing England. The stakes were just as high, and once again, Viv Richards stood tall. He walked in with the pressure thick in the air, he scored 138 off 157 balls, He was named Man of the Match, and West Indies lifted their second consecutive World Cup.

In 1980, Viv played a Test in Multan under 40°C heat. He scored 182 not out, chewing gum and batting with sunglasses on.

In the early 1980s, cricket’s world was shaken by offers of money to play in apartheid South Africa. A rebel West Indies tour was being planned, and players were tempted with blank cheques.

Viv Richards got the call too. Twice once in 1983, again in 1984. The sums were staggering. But Viv didn’t hesitate. He said NO.

His words were simple: “I couldn’t play for money in a land where my people weren’t free.”

That refusal cost him millions. But it won him something far greater...respect. Across the Caribbean, across Africa, across the world, people saw not just a cricketer, but a man of conviction.

In 1980, Viv played a Test in Multan under 40°C heat. He scored 182 not out, chewing gum and batting with sunglasses on.

In the early 1980s, cricket’s world was shaken by offers of money to play in apartheid South Africa. A rebel West Indies tour was being planned, and players were tempted with blank cheques.

Viv Richards got the call too. Twice once in 1983, again in 1984. The sums were staggering. But Viv didn’t hesitate. He said NO.

His words were simple: “I couldn’t play for money in a land where my people weren’t free.”

That refusal cost him millions. But it won him something far greater...respect. Across the Caribbean, across Africa, across the world, people saw not just a cricketer, but a man of conviction.

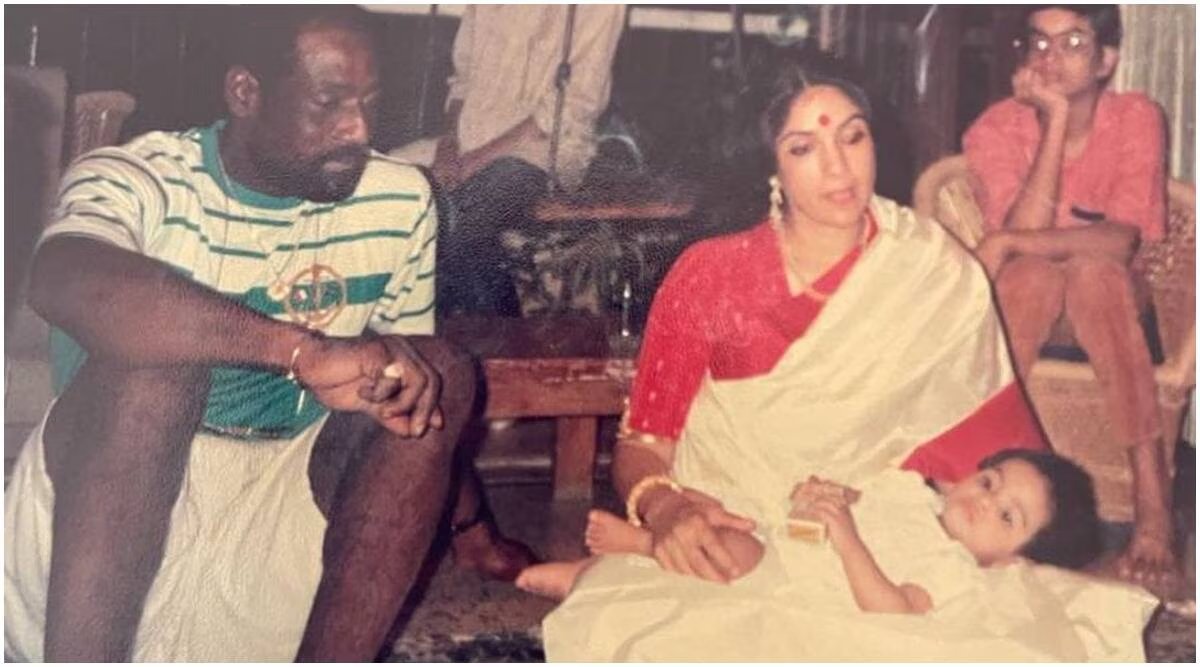

In the 1980s, during a West Indies tour of India, Viv Richards met Neena Gupta, Key role in the hit series Panchayat. Viv was already a married man. What began as a friendship soon turned into something deeper.

Not long after, Neena discovered she was pregnant. Viv, still tied to his life back home, wasn’t sure about fathering a child at that point. But Neena was clear. She chose not to have an abortion. She decided to raise the child, on her own terms, in India, without apology. That child was Masaba Gupta, now a fashion designer.

Growing up, Masaba lived under the glare of questions and assumptions. But Neena stood strong, and Viv, though distant, never truly disappeared. He didn’t make promises he couldn’t keep but he kept the door open. And over time, Masaba and Viv began meeting. Slowly, a quiet bond took shape. On her 18th birthday, Masaba received a handwritten letter from him. In it, Viv Richards wrote:

“You were born of courage. You are not a secret—I’m proud of you.”

Not long after, Neena discovered she was pregnant. Viv, still tied to his life back home, wasn’t sure about fathering a child at that point. But Neena was clear. She chose not to have an abortion. She decided to raise the child, on her own terms, in India, without apology. That child was Masaba Gupta, now a fashion designer.

Growing up, Masaba lived under the glare of questions and assumptions. But Neena stood strong, and Viv, though distant, never truly disappeared. He didn’t make promises he couldn’t keep but he kept the door open. And over time, Masaba and Viv began meeting. Slowly, a quiet bond took shape. On her 18th birthday, Masaba received a handwritten letter from him. In it, Viv Richards wrote:

“You were born of courage. You are not a secret—I’m proud of you.”

By 1984, Viv Richards was more than just the face of West Indies cricket. He was its soul. That year, he was named captain. In the next few years, he captained the West Indies in 50 Test matches, won 27, lost just 8. More importantly, he never lost a Test series. Not once. No other West Indies captain has matched that.

In 1986, at the Antigua Recreation Ground, Viv scored the fastest Test century ever at the time, 100 off 56 balls, finishing on 110 off 58. He hit seven sixes, including one that shattered a bottle of rum in the stands.

In 1991, after his final Test match, the dressing room in Antigua was quiet. Teammates celebrated. But Viv sat in a corner with his bat resting across his knees. He didn’t speak. For hours. Later, a groundsman found him alone, wiping his eyes with the sleeve of his shirt.

In 1986, at the Antigua Recreation Ground, Viv scored the fastest Test century ever at the time, 100 off 56 balls, finishing on 110 off 58. He hit seven sixes, including one that shattered a bottle of rum in the stands.

In 1991, after his final Test match, the dressing room in Antigua was quiet. Teammates celebrated. But Viv sat in a corner with his bat resting across his knees. He didn’t speak. For hours. Later, a groundsman found him alone, wiping his eyes with the sleeve of his shirt.

Knighted in 1999.

Named Wisden’s Cricketer of the Century in 2000.

Inducted into the ICC Hall of Fame in 2009.

By then, the numbers were already legend:

8,540 Test runs. 24 centuries.

6,721 ODI runs. 11 tons.

Two World Cups.

Zero Test series lost as captain.

But Viv Richards was never just about numbers.

He was about presence.

Named Wisden’s Cricketer of the Century in 2000.

Inducted into the ICC Hall of Fame in 2009.

By then, the numbers were already legend:

8,540 Test runs. 24 centuries.

6,721 ODI runs. 11 tons.

Two World Cups.

Zero Test series lost as captain.

But Viv Richards was never just about numbers.

He was about presence.

If you liked this thread, do follow for more stories like this. And if it moved you, please retweet so it can reach more cricket lovers out there.

Thank you for reading.

Thank you for reading.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh