🚨New paper in @TrendsCognSci 🚨

Why do some ideas spread widely, while others fail to catch on?

@Jayvanbavel and I review the “psychology of virality,” or the psychological and structural factors that shape information spread online and offline.

Thread 🧵(1/n)

Why do some ideas spread widely, while others fail to catch on?

@Jayvanbavel and I review the “psychology of virality,” or the psychological and structural factors that shape information spread online and offline.

Thread 🧵(1/n)

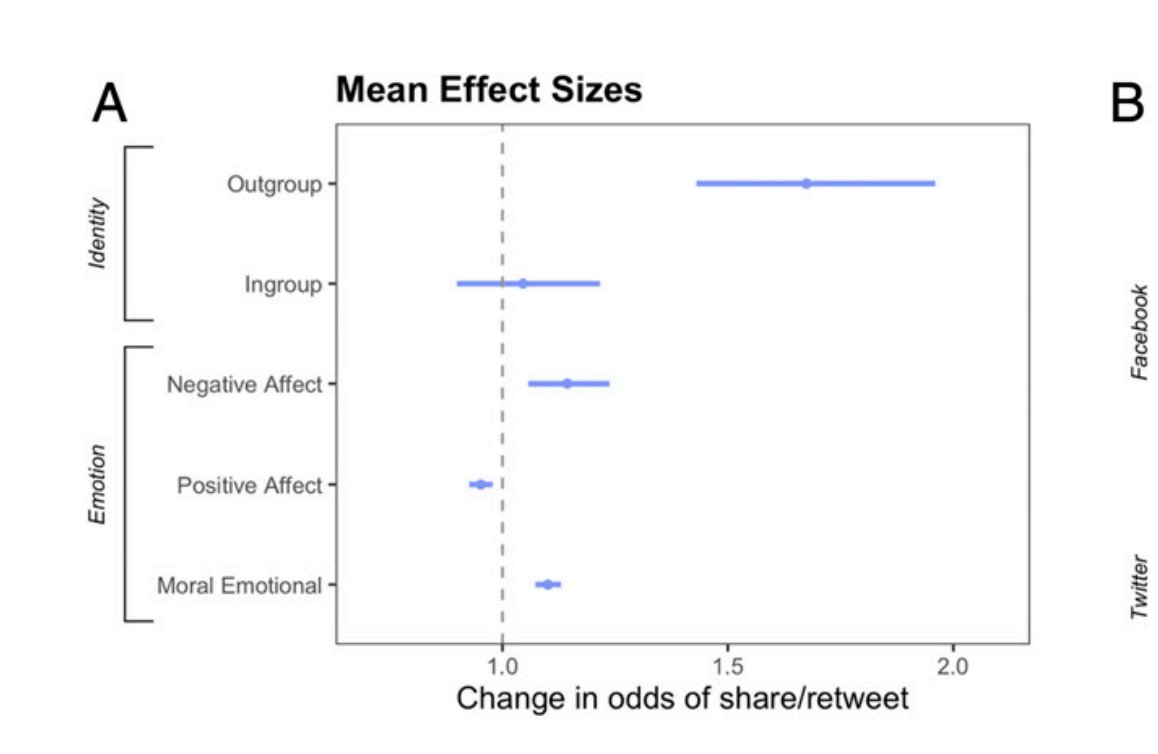

While studies suggest that outrage and negativity go viral online, social media may not be so unique:

-Negative gossip and word-of-mouth marketing is also likely to spread.

-Negativity went “viral” in early newspapers and books.

-Negative gossip and word-of-mouth marketing is also likely to spread.

-Negativity went “viral” in early newspapers and books.

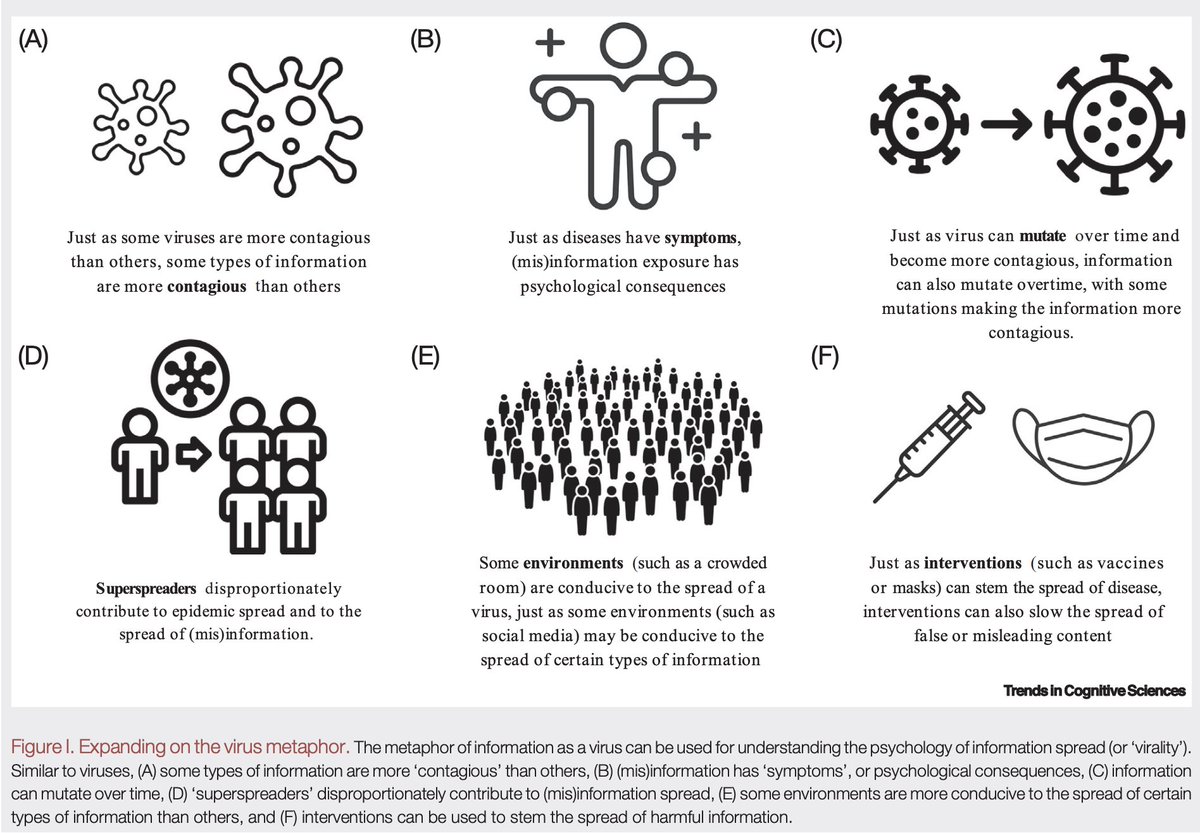

Similar to how some viruses are more “contagious” than others, some forms of information appear to be more contagious than others across contexts.

The information-as-virus metaphor can be extended even further:

The information-as-virus metaphor can be extended even further:

Underlying psychological processes (e.g., our tendency to attend to and remember negativity and high-arousal information) may explain why certain types of information go "viral" across contexts.

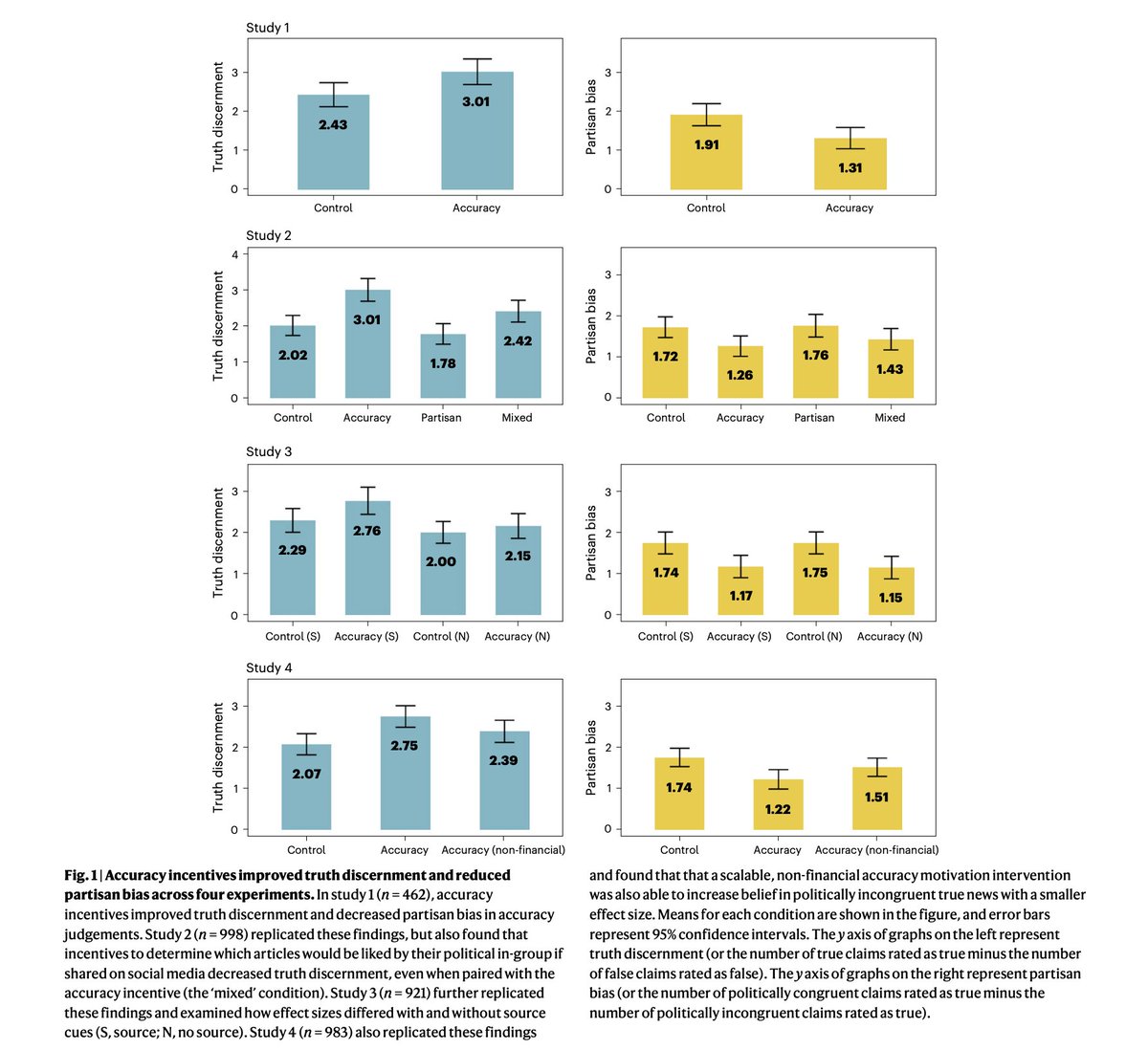

We review several studies in the virality literature. Most of them find that negativity and high-arousal emotions go viral. Yet, not all studies support this conclusion, and sometimes positivity goes viral. Why is that?

Structural features of an information environment (e.g., networks, norms, incentive structures) interact with our psychology to shape information spread, which may help explain conflicting findings.

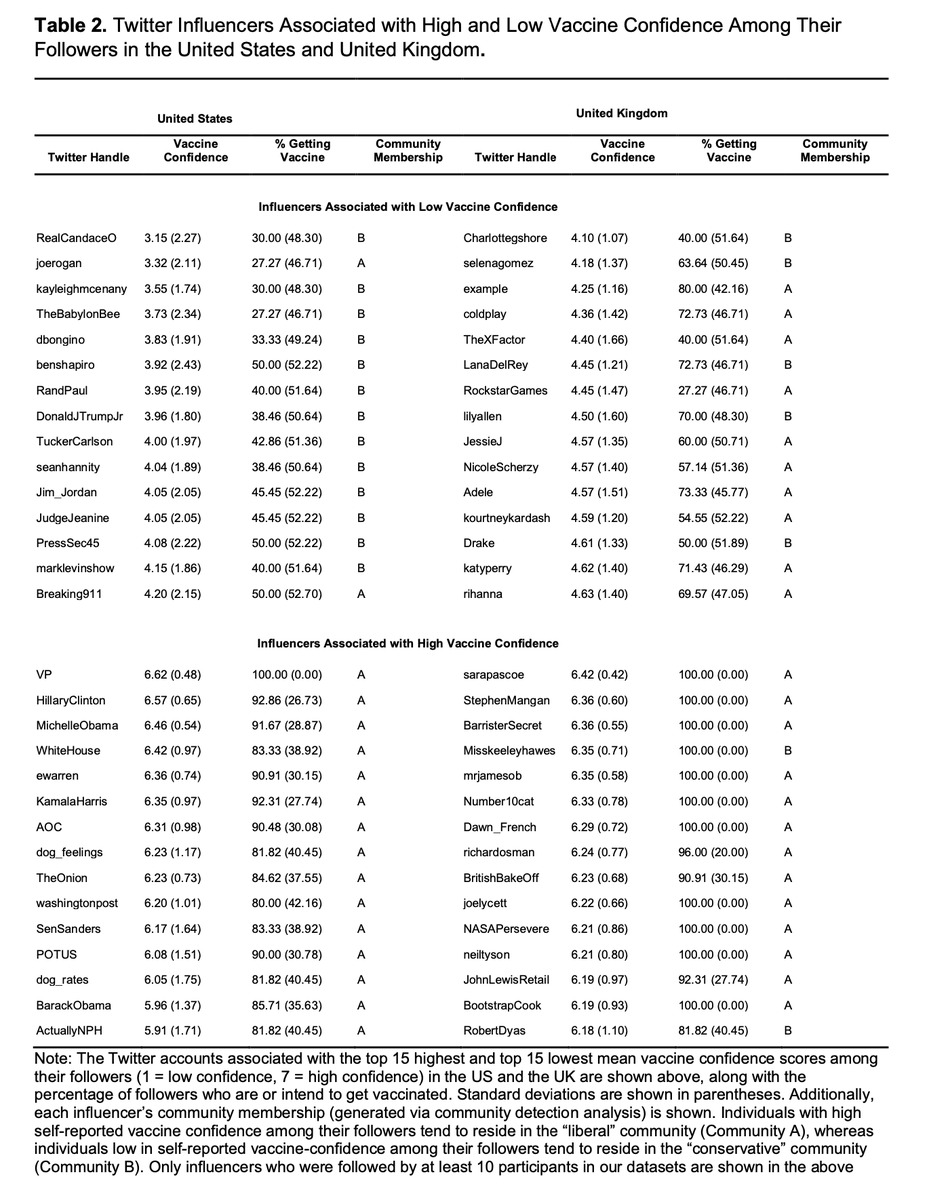

The online world has unique structural features: for example, a small number of “superspreaders” spread the most hostility in all contexts, but hostile individuals have a much larger reach online due to larger networks and attention-maximizing social media algorithms.

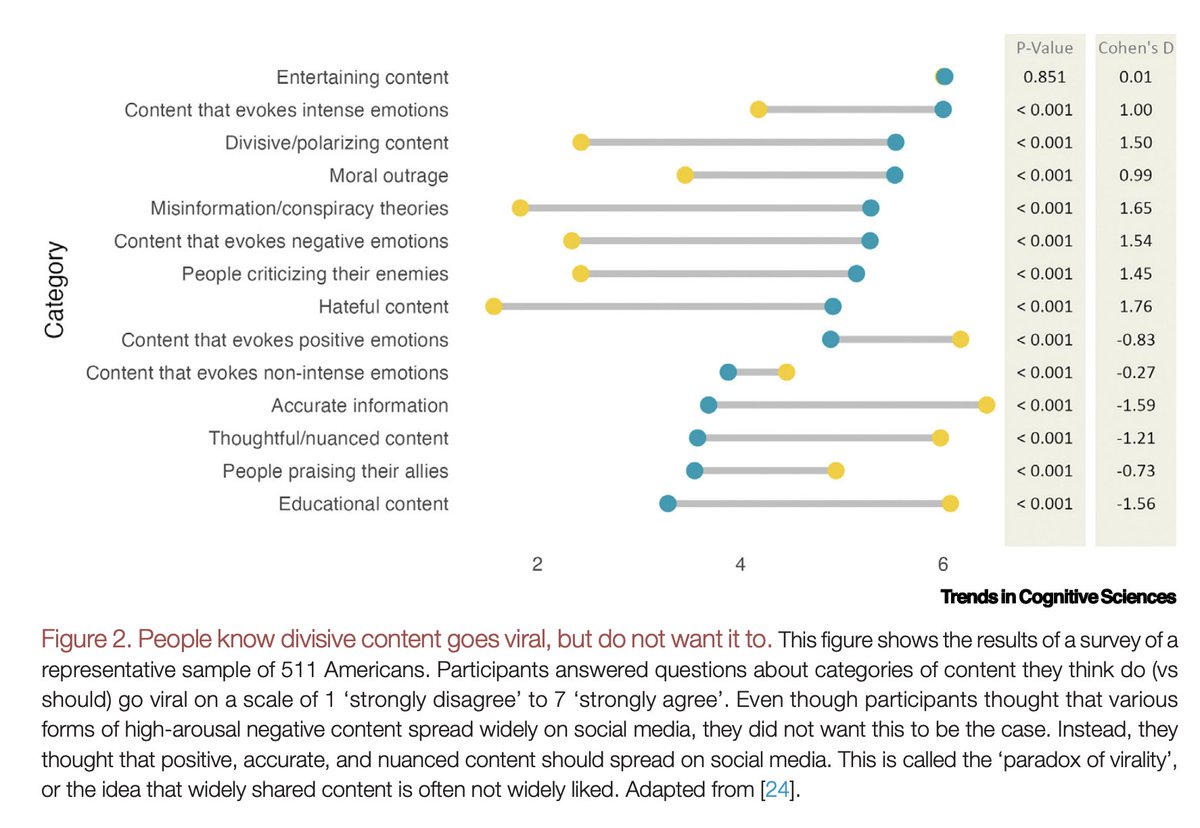

This may explain, in part, why widely shared content is often not widely liked, a phenomenon we call the “paradox of virality” (): journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.117…

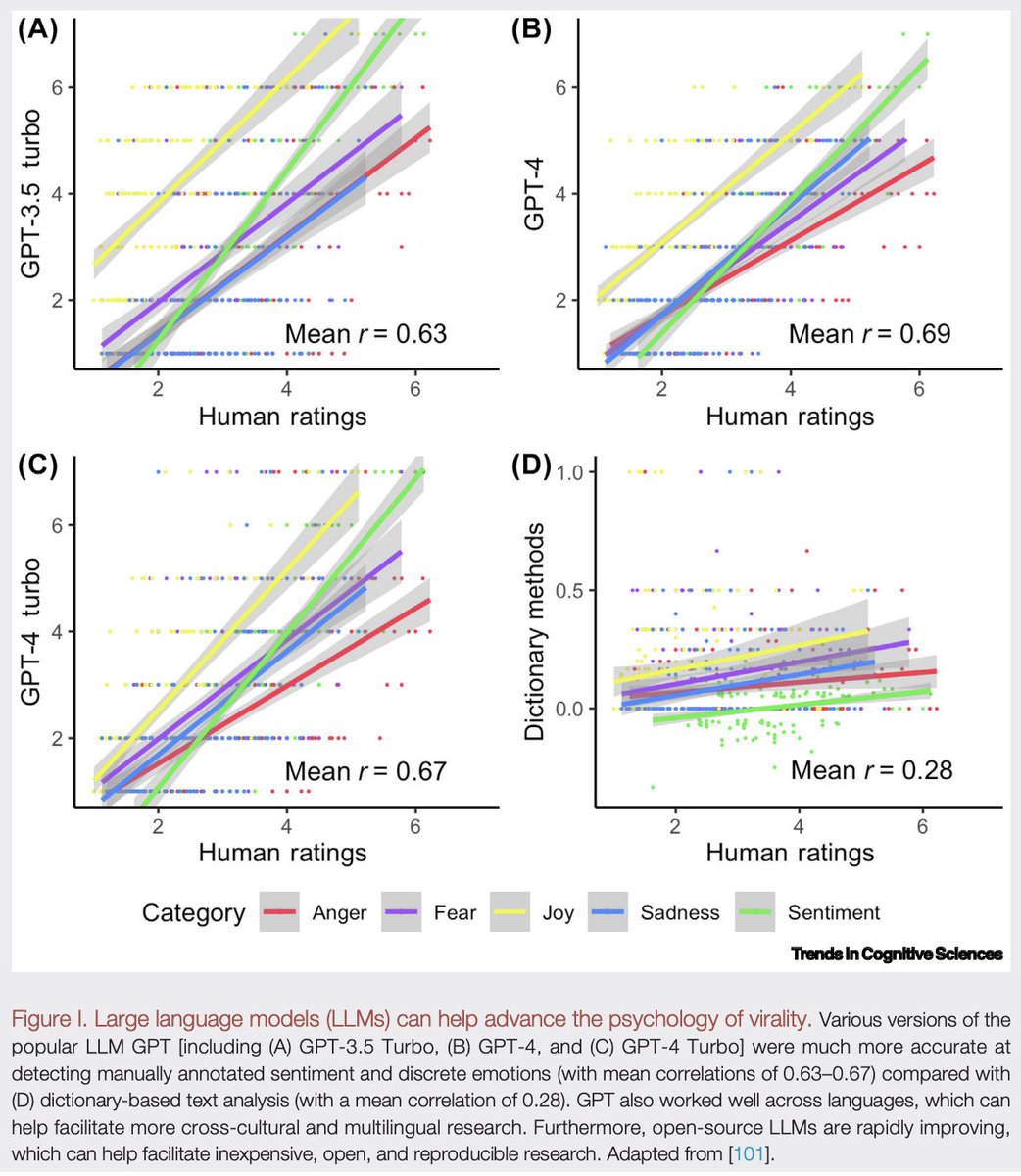

Future work on virality should leverage recent advances in AI () to explore what goes “viral” across languages, cultures, and time periods. pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pn…

Check out the full paper here: authors.elsevier.com/c/1lRke4sIRvW-…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh