Shīʿī Reports and HCM:

In the Sunnī tradition, the primary subject of attribution is the Prophet himself. Tracing a report back to the Prophet is difficult due to various methodological concerns that have been highlighted in the relevant scholarship.

In the Sunnī tradition, the primary subject of attribution is the Prophet himself. Tracing a report back to the Prophet is difficult due to various methodological concerns that have been highlighted in the relevant scholarship.

In the Shī'ī Ḥadīth, the attributions are primarily directed towards al-Sadiq and al-Bāqir. Historically confirming their reports is likely easier some of their contemporaries are already established common links; al-Zuhri and Hisham b. ʿUrwa are already arrested.

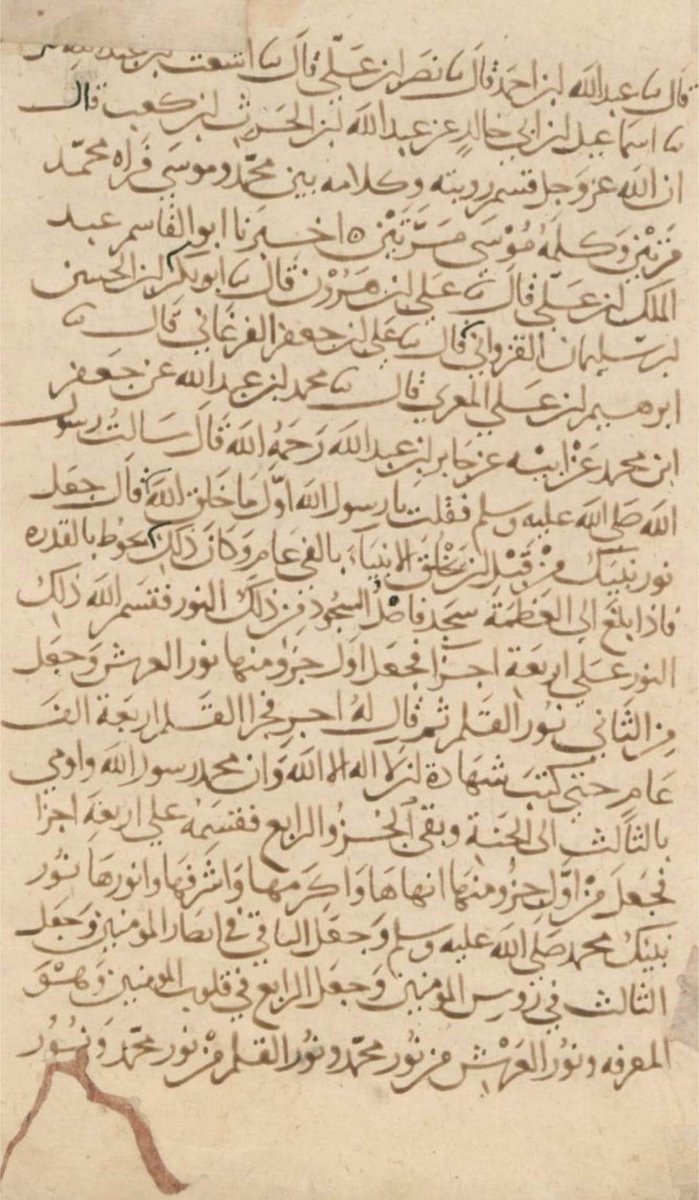

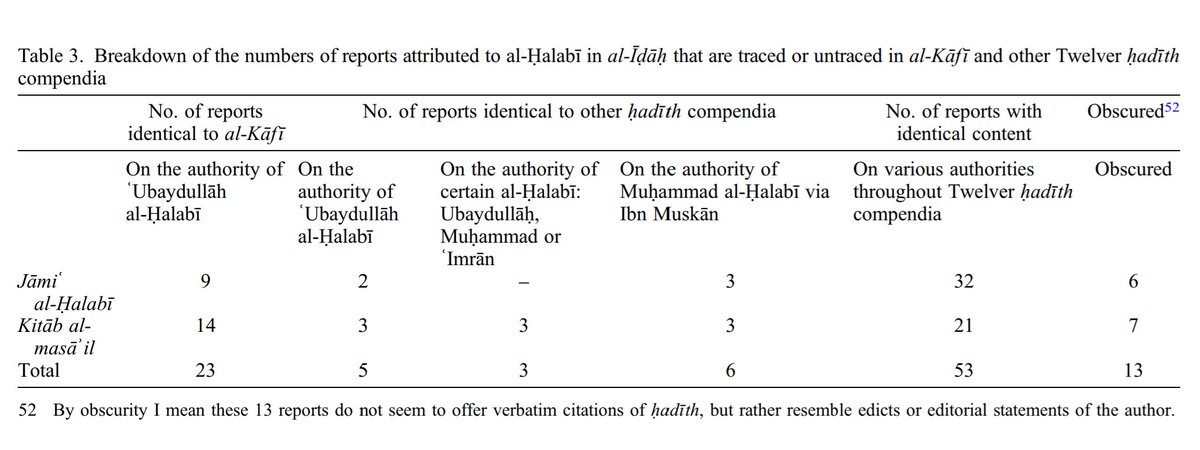

Using cross-regional analysis of reports, Rajani was able to reconstruct an earlier layer of Shi'i texts which was common for both Ismailis and Imāmis. It is likely that these reports came from the Aṣl of Ḥalabī who was a companion of Imām Jaʿfar.

Even Sunni corpus likely preserves historical reports of Imām Jaʿfar. Many reports are corroborated in both Sunni and Shi'i corpus. Ammar Muslim has shown that in the case of accepting a witness with an oath.

For a further example of a tradition that can likely be attributed to Imām Jaʿfar due to independent attestations by Ismaili and Imāmī sources, see:

https://x.com/ShaykhIshraq/status/1946110886806016166?t=u3GRiMeagVrUCiX5V-ZnRg&s=19

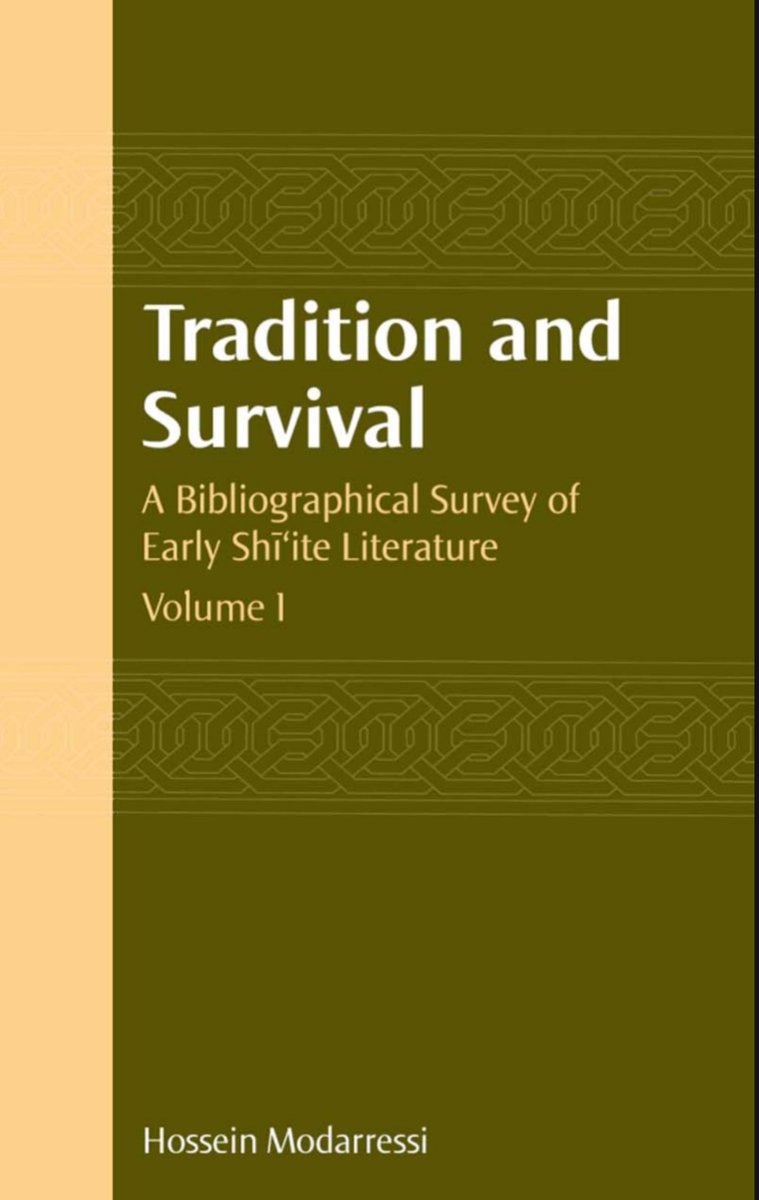

In addition to this, Modarressi attempts to reconstruct many reports from various Uṣūl. For that, see:

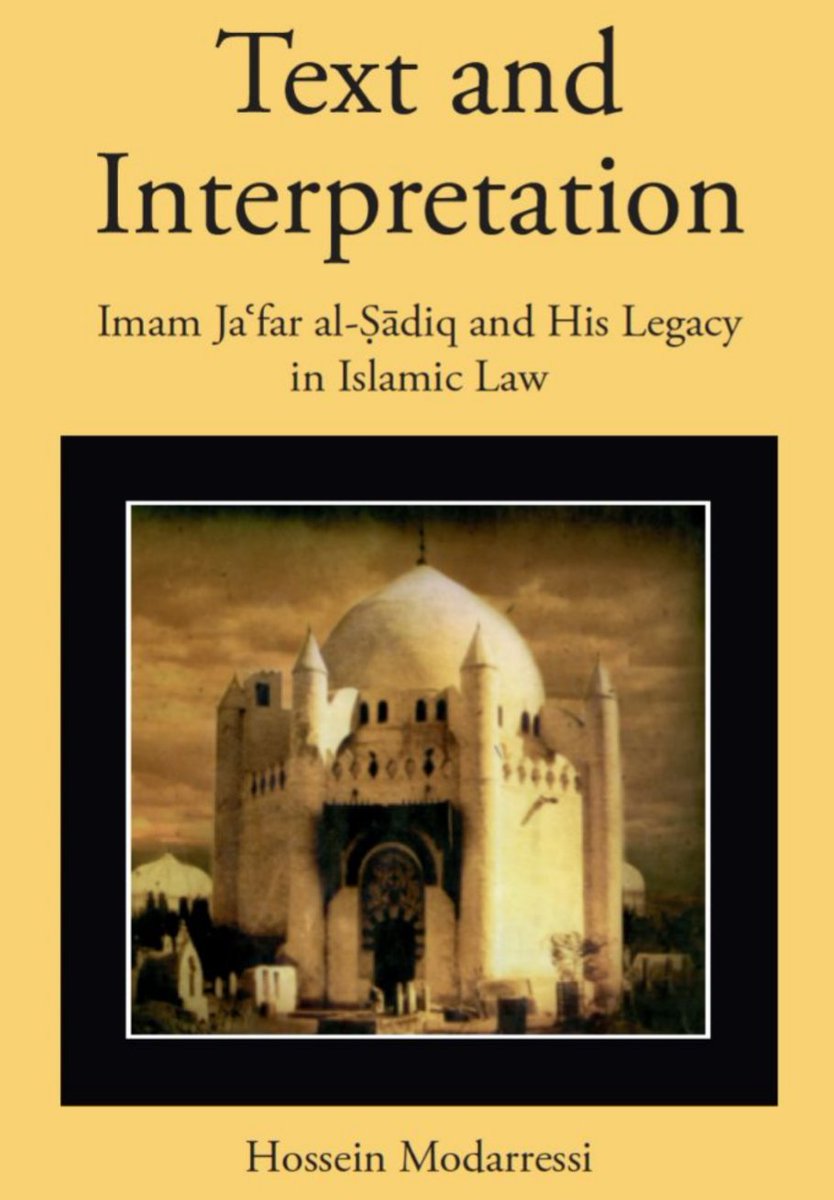

In his monograph on Imām Jaʿfar, he cites multiple traditions from both Shīʿī and Sunni sources. He considers these historical based on his historical methodology:

Based on these studies, it is plausible that some content in Sunni, Shi'i, and Zaydi Ḥadīth corpora can be traced back to the historical Imāms such as Imām Jaʿfar. The nature of this reconstruction is fundamentally different to the Prophetic reports.

Add:

Another report that can likely be traced back to an earlier layer.

Another report that can likely be traced back to an earlier layer.

https://x.com/TahaNaqvi114/status/1812272608966295882?t=vhnyFJfsh6tXYBBlJ6Rfng&s=19

Add:

Even polemical skepticism on Shi'i corpus is valid. The problem with the rhetoric supported by @Farid_0v and @MrAdnanRashid is that they are skeptical towards a corpus that likely preserves content for which the attributed authority is the CL but...

Even polemical skepticism on Shi'i corpus is valid. The problem with the rhetoric supported by @Farid_0v and @MrAdnanRashid is that they are skeptical towards a corpus that likely preserves content for which the attributed authority is the CL but...

they accept a corpus for which no CL for the primary authority can be reconstructed. That is the major issue.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh