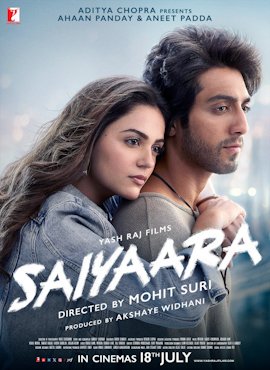

Saiyaara is an utterly mediocre film—of that there’s no doubt. But the rapturous reception it’s received, from both audiences and critics, deserves some analysis, especially because it’s ended Bollywood’s long dry spell.

A thread.

1/27.

A thread.

1/27.

What makes Saiyaara even more notable? That it’s a romantic drama. Bollywood used to ace that genre once but now shows signs of Alzheimer’s. Before Saiyaara, though, let’s ask ourselves this: When did Bollywood romance truly die? December 2016, when Befikre released.

2/27.

2/27.

Produced by YRF, which also backed Saiyaara, Befikre’s director, Aditya Chopra, made the most iconic love story, DDLJ, but who, two decades later, was trying to catch up, using meta references to please his new audiences, which had raced past him. I’ll give two examples.

3/27.

3/27.

Did Befikre’s first scene, with different couples kissing publicly, remind you of another film? Dil To Pagal Hai, written by Chopra, whose opening credits had varied couples, from different age groups and class, holding hands—very cute, very platonic, very (old) B’wood.

4/27.

4/27.

Befikre’s opening scene strives for a ‘temporal adaptation’, or desperation, indicating, ‘Isn’t this what modern love is all about, lust at first sight?’ If only it were that simple.

5/27.

5/27.

Later, when the heroine is looking at the back of a guy who had asked her out, the hero says, “Palatne nahin waala hai woh [he won’t turn back]”—referencing DDLJ. She replies, “Log palat-te toh ’90s me the [people used to turn back in the ’90s]. I was just checking his ass.” 6/27

You know (traditional) Bollywood romance has died when even Aditya Chopra makes fun of DDLJ.

7/27.

7/27.

An early scene in Saiyaara, where the movie introduces its hero, mirrors Jab We Met—hard. There, a jilted hero; here, a jilted heroine. There, a chatty woman; here, a dude smoking a joint on a bike. There, a Manic Pixie Dream Girl; here, a ‘Maniac Toxie Dream Boy’.

8/27

8/27

So what changed in B’wood? Sandeep Vanga’s Animal. Saiyaara’s hero is nuts. He pummels strangers, boils with rage, derides his friend (a sidekick who solidifies the hierarchy further). Later, the reference becomes overt, when we hear, “That Krish Kapoor is an Animal.”

9/27

9/27

This is Stockholm Syndrome masquerading as a ‘love story’. Krish is so unhinged that every ‘good’ thing he does, especially in the second half, feels like a favour. In the first half, the heroine, Vaani, almost looks scared around him.

10/27.

10/27.

His masculinity almost looks colonial (‘I’ll wage a war if I don’t get what I deserve’), blurring the lines between assertion and aggression, confidence and cannibalism. It’s not enough that the man exists; he must exist at everyone else's expense. He’ll win; she’ll cheer.

11/27

11/27

Like Animal’s hero, Krish suffers from daddy issues. His dick waving continues throughout the first half to the extent that even his problem is bigger than hers. She’s trying to be vulnerable; he’s playing cricket, idolising Kohli, another masculine icon. (It’s ludicrous.)

12/27

12/27

Not that the director’s intention matters while analysing a film (the text provides its own evidence), but still, Mohit Suri is a Vanga fan. Just listen to this snippet, where he expresses regret about not praising Animal online.

.

13/27.

.

13/27.

https://x.com/rayfilm/status/1947350966912659466

But at least two differences distinguish Saiyaara from Animal (which, too, is mediocre—even if there were no such thing as misogyny—but it’s v fascinating). The first: Unlike Animal's world, where ‘inferior men’ write poetry, Krish does (kinda) write poetry (he’s a singer). 14/27

The second difference: If Krish has to contend with Madonna (in the psychoanalytical framework the ‘Madonna-whore complex’), then Animal's hero conquers both Madonna and the whore (truly an alpha).

15/27.

15/27.

The similarities between the two films go on and on, and on and on. Saiyaara’s heroine almost always exists with respect to the hero (she even laughs for the first time when he cracks a joke). Then, there’s the hint of relationship between men in Saiyaara.

16/27.

16/27.

At one point, Krish meets Vaani’s parents. Her hysterical mother shouts at Vaani, while her father and Krish share sympathetic silence. (It recurs soon when the father tells Krish that he can stay at the hospital, while the mother resembles a crabby old cat).

17/27.

17/27.

It’s B’wood version of an obvious truth (extrapolated in Animal with no self-awareness): that men talk about women, that men pursue women, that men fixate on women. But men truly want other men. They want their approval, comfort, love—men only want to be seen by other men. 18/27.

Make your hero masculine—no problem. (Remember Bachchan’s Angry Young Man?) But many B’wood filmmakers don’t understand masculinity. Even worse, their heroes’ masculinity has an invading intent (which thrives by decimating everyone but his partner who enjoys servility).

19/27.

19/27.

Forget morality, such a story is so linear (like a ‘gendered propaganda’) that it borders on the tedious and the juvenile. But what do I know? It’s worked. So that crucial shift in heroes will continue to mark many Hindi films in the future, romantic or otherwise.

20/27.

20/27.

You can find strains of that man in Rockstar, Tamasha, Ae Dil Hai Mushkil, and so on. But unlike Salim-Javed’s dramas, the recent movies don’t contemplate his rage. (The flimsy ‘daddy issue’ or heartbreak just doesn’t cut it because here the anger is ginormous.)

21/27

21/27

This masculine fetish has been further intensified by other blockbusters, such as Pushpa, KGF, etc. Most audience reactions to Saiyaara praise its (mediocre) hero and trace his origin, via old clips, and ignore the (convincing) heroine, as if she doesn’t even exist.

22/27

22/27

This reaction complements the film (which turns her into a comic relief in the second half). But yes, Saiyaara has definitely shifted something in B’wood. It doesn’t even look like a YRF romance. It reminded me more of Mukesh Bhatt’s Vishesh Films.

23/27

23/27

And it, of course, reminded me of the Bega banger: ‘A Little bit of Woh Lamhe in my life/A little bit of Animal by my side/A little bit of Tamasha’s all I need/A little bit of Aashiqui’s what I see.’

24/27

24/27

Towards the end, when the titular Saiyaara song came, something strange happened in my screening in South Delhi. Two women to my left held their phones up, filming the song; so did a man to my right. Bizarre. But not just these three folks.

25/27

25/27

Two people in front also flashed their phones. I craned my neck: Over a dozen people had their phones out. If they were recording while watching, I thought, were they even watching? Or did they want to be watched while being watched, sharing the clip later on social media?

26/27

26/27

I can keep analysing their behaviour, but one thing was for sure, I was in the middle of an epochal event: An age had found its language, a generation had found its film. We get the cinema we deserve.

Fin.

27/27.

Fin.

27/27.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh