Freedom has a marketing problem.

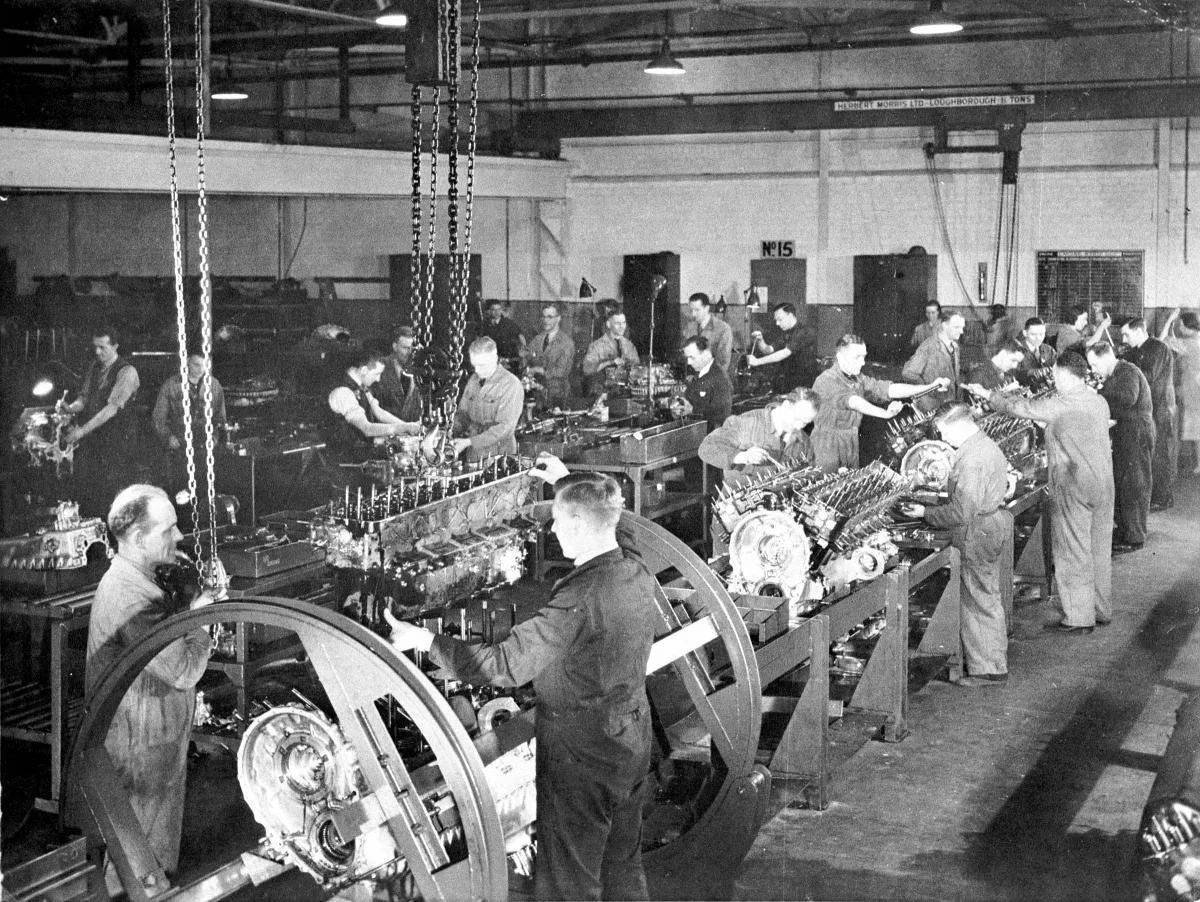

We have the greatest product in human history. Individual liberty has created more prosperity, ended more suffering, and unleashed more potential than any idea ever conceived.

Yet we're getting destroyed by people promising free stuff while delivering famines. 🧵

We have the greatest product in human history. Individual liberty has created more prosperity, ended more suffering, and unleashed more potential than any idea ever conceived.

Yet we're getting destroyed by people promising free stuff while delivering famines. 🧵

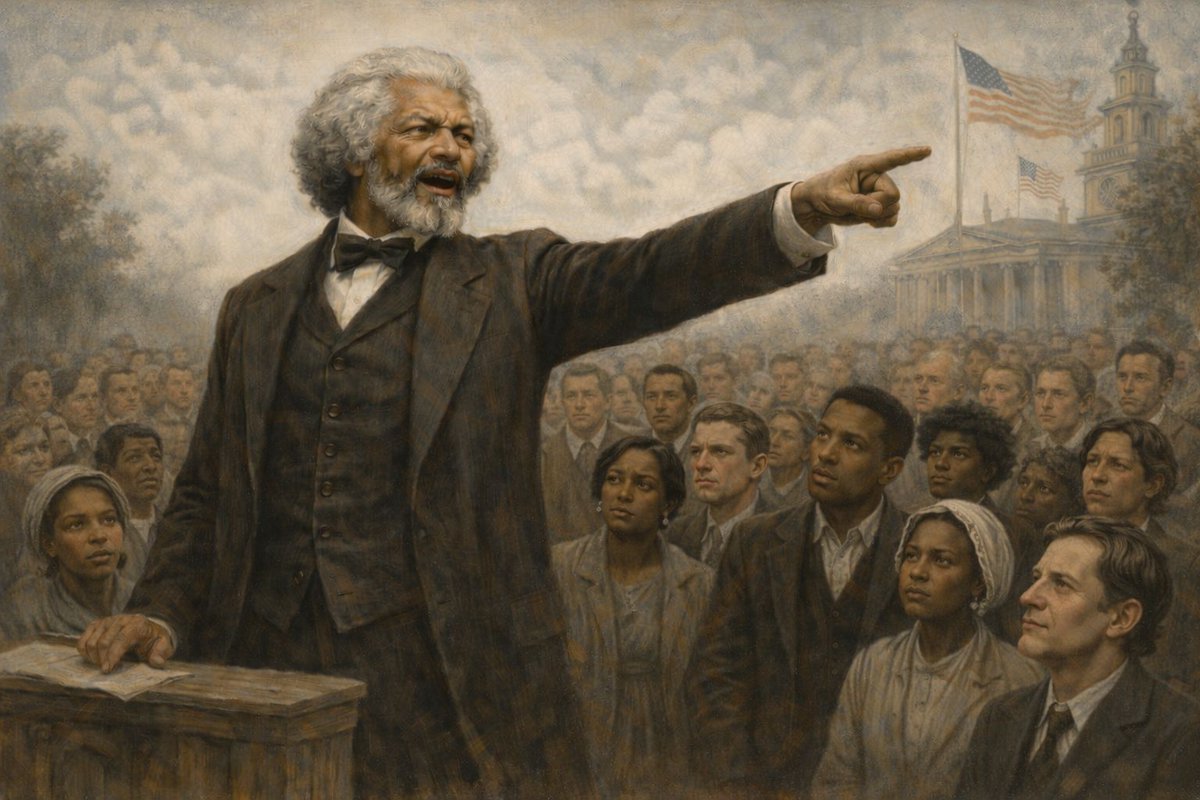

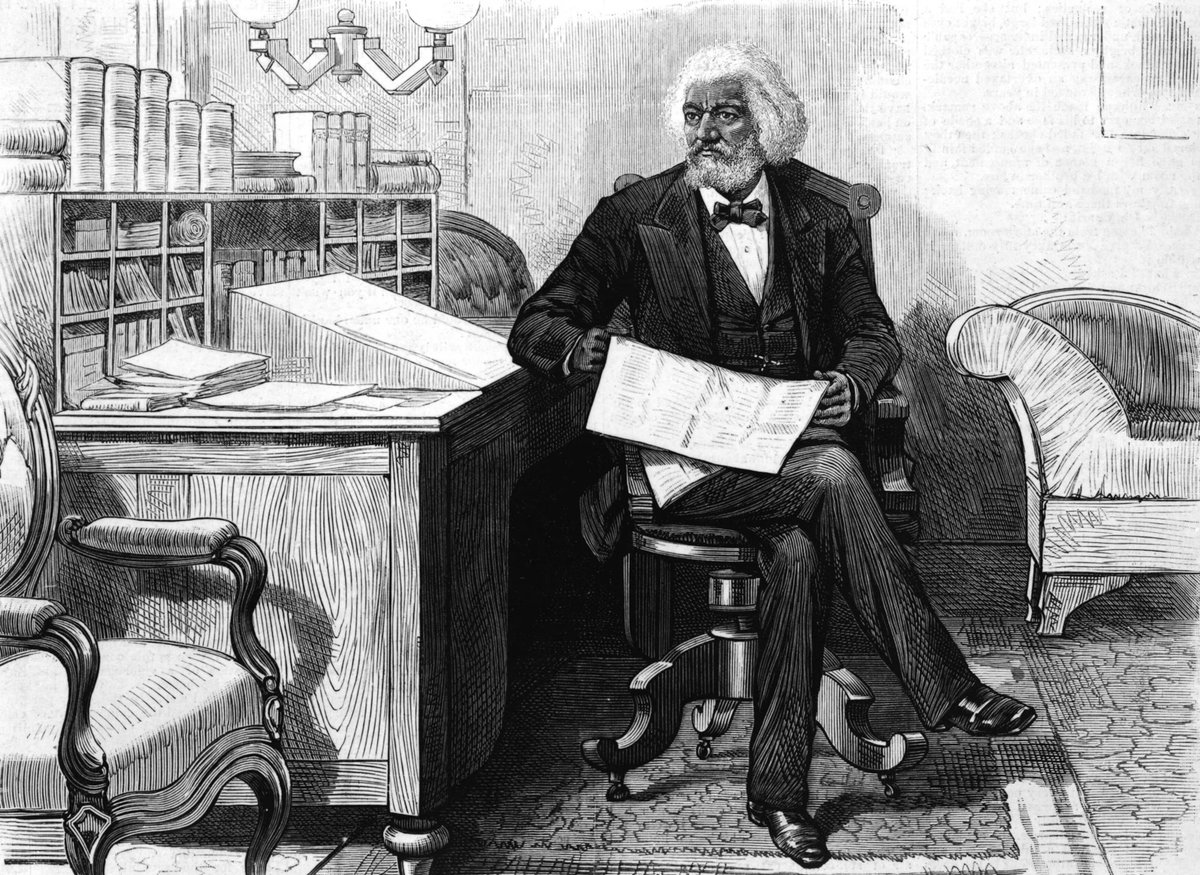

Think about this historical irony: In the 1800s, we were the revolutionaries. We tore down kings, ended slavery, gave power to the people.

Now we sound like we're defending a broken system instead of offering something better.

What happened?

Now we sound like we're defending a broken system instead of offering something better.

What happened?

Here's why we keep losing: We defend the world as it exists instead of selling the world we want to create.

Someone complains about expensive healthcare? We lecture them about Obamacare instead of explaining how the state prevents cheaper, better options from existing.

It's like a waiter lecturing you about poor eating habits when you say you're hungry instead of offering food.

Someone complains about expensive healthcare? We lecture them about Obamacare instead of explaining how the state prevents cheaper, better options from existing.

It's like a waiter lecturing you about poor eating habits when you say you're hungry instead of offering food.

The problem isn't our ideas. It's our salesmanship.

When someone says "capitalism is unfair," we shouldn't defend crony capitalism. We should say: "You're right. That's why we need real free markets that destroy monopolies and give everyone a chance."

Great selling starts with understanding the customer's problem.

When someone says "capitalism is unfair," we shouldn't defend crony capitalism. We should say: "You're right. That's why we need real free markets that destroy monopolies and give everyone a chance."

Great selling starts with understanding the customer's problem.

Student debt crushing you? Educational freedom creates better, cheaper alternatives.

Can't afford housing? Zoning reform and free markets build millions of affordable homes.

Healthcare bankrupting families? Real competition slashes costs.

We solve their actual problems. We just forgot how to communicate it.

Can't afford housing? Zoning reform and free markets build millions of affordable homes.

Healthcare bankrupting families? Real competition slashes costs.

We solve their actual problems. We just forgot how to communicate it.

Every conversation is a chance to win or lose a mind. Every debate is recruiting for their side or ours.

The future of human freedom literally depends on whether we can inspire people instead of lecture them.

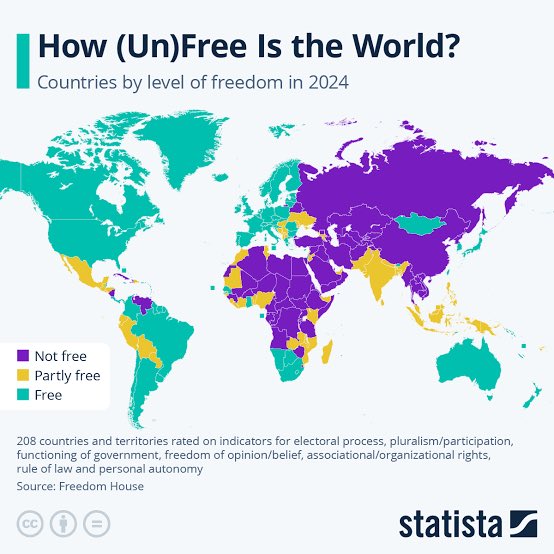

This isn't just politics. It's whether the next generation grows up free or enslaved.

The future of human freedom literally depends on whether we can inspire people instead of lecture them.

This isn't just politics. It's whether the next generation grows up free or enslaved.

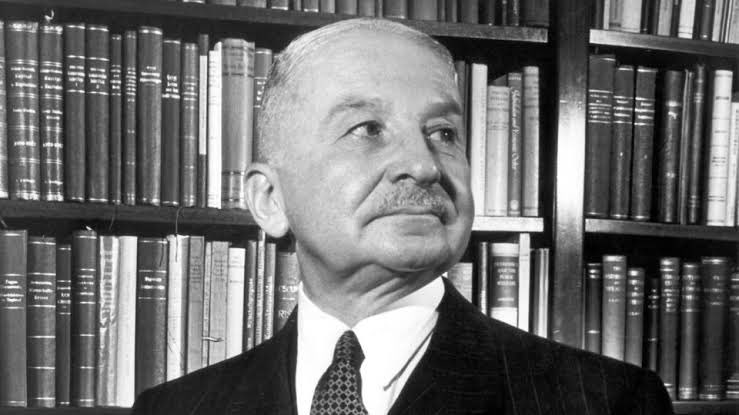

Ludwig von Mises saw this coming decades ago. He warned that "everyone carries a part of society on his shoulders." We can't stand aside while bad ideas take over.

"Whether he chooses or not, every man is drawn into the great historical struggle."

We're in that battle right now. And we're losing because we forgot how to fight.

"Whether he chooses or not, every man is drawn into the great historical struggle."

We're in that battle right now. And we're losing because we forgot how to fight.

Ready to become a liberty advocate who actually wins minds?

We're looking for student leaders who want to learn how to sell freedom instead of just defending the status quo.

Apply to be a Local Coordinator and join 2,000+ students in 100+ countries building the liberty movement:

👉 join.studentsforliberty.org

We're looking for student leaders who want to learn how to sell freedom instead of just defending the status quo.

Apply to be a Local Coordinator and join 2,000+ students in 100+ countries building the liberty movement:

👉 join.studentsforliberty.org

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh