Battle of the Crater and the Siege of Petersburg 🧵

1/ On July 30, 1864, the Battle of the Crater erupted during the Siege of Petersburg, Virginia—a grueling 9-month campaign that foreshadowed WWI trench warfare. Union Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s 100,000 troops besieged Gen. Robert E. Lee’s 50,000 Confederates defending Petersburg, a key rail hub supplying Richmond. The Crater involved a Union mine explosion under Confederate lines, creating chaos but ending in disaster. Total siege casualties exceeded 70,000; the Crater alone claimed 5,300. This thread details the siege’s buildup, the Crater’s drama, and its impact—a brutal chapter in the Civil War’s final year.

1/ On July 30, 1864, the Battle of the Crater erupted during the Siege of Petersburg, Virginia—a grueling 9-month campaign that foreshadowed WWI trench warfare. Union Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s 100,000 troops besieged Gen. Robert E. Lee’s 50,000 Confederates defending Petersburg, a key rail hub supplying Richmond. The Crater involved a Union mine explosion under Confederate lines, creating chaos but ending in disaster. Total siege casualties exceeded 70,000; the Crater alone claimed 5,300. This thread details the siege’s buildup, the Crater’s drama, and its impact—a brutal chapter in the Civil War’s final year.

Background to the Siege of Petersburg

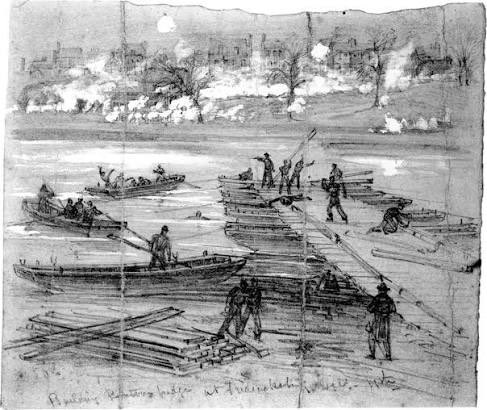

2/ By spring 1864, Grant’s Overland Campaign had bloodied Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia through battles like the Wilderness and Spotsylvania, costing 55,000 Union casualties. Grant shifted south, crossing the James River to target Petersburg—Richmond’s lifeline with five railroads. Capturing it would starve the Confederate capital. Lee, anticipating the move, rushed troops to defend the city’s 10-mile fortifications. On June 15, Union Maj. Gen. William F. Smith probed but delayed, allowing Lee to reinforce. The siege began as Grant opted for encirclement over direct assault, setting a prolonged stalemate.

2/ By spring 1864, Grant’s Overland Campaign had bloodied Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia through battles like the Wilderness and Spotsylvania, costing 55,000 Union casualties. Grant shifted south, crossing the James River to target Petersburg—Richmond’s lifeline with five railroads. Capturing it would starve the Confederate capital. Lee, anticipating the move, rushed troops to defend the city’s 10-mile fortifications. On June 15, Union Maj. Gen. William F. Smith probed but delayed, allowing Lee to reinforce. The siege began as Grant opted for encirclement over direct assault, setting a prolonged stalemate.

Union Arrival and Initial Attacks

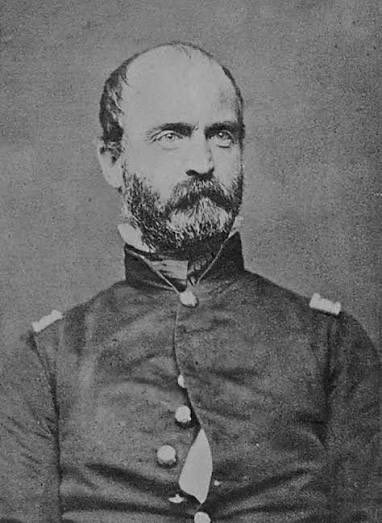

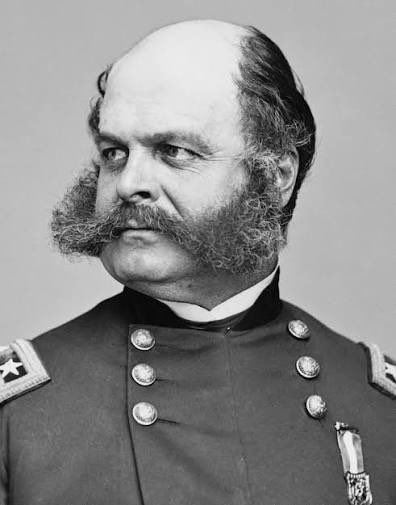

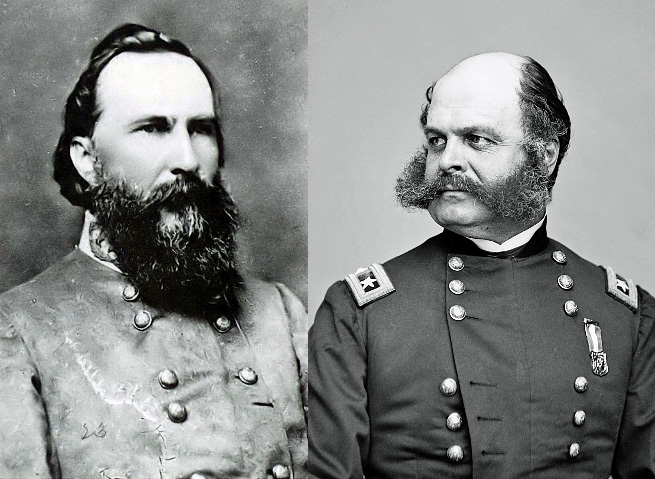

3/ Grant’s forces arrived at Petersburg on June 15, 1864, with 18,000 troops under Smith facing just 2,200 Confederates. Hesitant attacks captured some outer works but failed to seize the city, costing 11,000 Union casualties over four days (June 15–18). Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s IX Corps and others charged fortified lines, met by enfilading fire. By June 18, Lee had 20,000 defenders entrenched. Grant, realizing a quick victory was impossible, ordered trenches dug, initiating a 292-day siege. Skirmishes and raids continued, extending lines to 35 miles as both sides burrowed in.

3/ Grant’s forces arrived at Petersburg on June 15, 1864, with 18,000 troops under Smith facing just 2,200 Confederates. Hesitant attacks captured some outer works but failed to seize the city, costing 11,000 Union casualties over four days (June 15–18). Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s IX Corps and others charged fortified lines, met by enfilading fire. By June 18, Lee had 20,000 defenders entrenched. Grant, realizing a quick victory was impossible, ordered trenches dug, initiating a 292-day siege. Skirmishes and raids continued, extending lines to 35 miles as both sides burrowed in.

Stalemate and Trench Warfare

4/ From late June 1864, Petersburg devolved into trench warfare, with soldiers enduring sniper fire, artillery barrages, and disease in muddy ditches. Union lines snaked around the city’s east and south, cutting railroads like the Weldon. Confederates built elaborate fortifications with abatis and bombproofs. Raids, like the June 22 Wilson-Kautz cavalry strike on rails, disrupted supplies but cost heavily. Heat, rats, and dysentery plagued both sides; desertions rose. Grant’s strategy: extend lines to overstretch Lee while probing weaknesses, turning the siege into a war of attrition that favored Union resources.

4/ From late June 1864, Petersburg devolved into trench warfare, with soldiers enduring sniper fire, artillery barrages, and disease in muddy ditches. Union lines snaked around the city’s east and south, cutting railroads like the Weldon. Confederates built elaborate fortifications with abatis and bombproofs. Raids, like the June 22 Wilson-Kautz cavalry strike on rails, disrupted supplies but cost heavily. Heat, rats, and dysentery plagued both sides; desertions rose. Grant’s strategy: extend lines to overstretch Lee while probing weaknesses, turning the siege into a war of attrition that favored Union resources.

The Crater Plan and Mining Operation

5/ By July 1864, Burnside’s IX Corps faced a Confederate salient 150 yards away. Lt. Col. Henry Pleasants, a mining engineer, proposed tunneling under it to plant explosives. Approved by Grant and Meade (skeptically), Pennsylvania coal miners dug a 511-foot shaft starting June 25, ventilating with an ingenious air system. By July 23, they placed 8,000 pounds of powder in galleries under the fort. The plan: detonate at dawn July 30, then assault through the breach with Maj. Gen. Edward Ferrero’s USCT division leading, followed by others to exploit the gap toward Petersburg.

5/ By July 1864, Burnside’s IX Corps faced a Confederate salient 150 yards away. Lt. Col. Henry Pleasants, a mining engineer, proposed tunneling under it to plant explosives. Approved by Grant and Meade (skeptically), Pennsylvania coal miners dug a 511-foot shaft starting June 25, ventilating with an ingenious air system. By July 23, they placed 8,000 pounds of powder in galleries under the fort. The plan: detonate at dawn July 30, then assault through the breach with Maj. Gen. Edward Ferrero’s USCT division leading, followed by others to exploit the gap toward Petersburg.

Preparations and Last-Minute Changes

6/ As the mine neared completion, tensions rose. Meade, fearing political fallout, replaced Ferrero’s trained Black troops with Ledlie’s inexperienced white division to lead the assault— a decision Grant approved. On July 29, fuses were set for a 3:30 AM blast. Over 15,000 Union troops massed, including Ferrero’s men in reserve. Confederates suspected tunneling but countermines failed to locate it. Lee reinforced the sector with Mahone’s division. Dawn approached amid high hopes for a breakthrough, but the plan’s alterations and poor leadership foreshadowed disaster.

6/ As the mine neared completion, tensions rose. Meade, fearing political fallout, replaced Ferrero’s trained Black troops with Ledlie’s inexperienced white division to lead the assault— a decision Grant approved. On July 29, fuses were set for a 3:30 AM blast. Over 15,000 Union troops massed, including Ferrero’s men in reserve. Confederates suspected tunneling but countermines failed to locate it. Lee reinforced the sector with Mahone’s division. Dawn approached amid high hopes for a breakthrough, but the plan’s alterations and poor leadership foreshadowed disaster.

The Explosion and Initial Chaos

7/ At 4:44 AM on July 30, after fuse failures and relighting, the mine detonated with a massive roar, hurling earth, guns, and 300 Confederates skyward. The blast created a 170-foot crater, 30 feet deep. Ledlie’s division charged but milled in the crater, trapped by steep walls and debris. Confederate survivors, stunned but rallying, fired from the rims. Elliott’s South Carolina brigade held the flanks. Union troops, leaderless (Ledlie hid in a bombproof), clustered helplessly as Confederates under Mahone counterattacked by 8:00 AM, turning the breach into a killing ground.

7/ At 4:44 AM on July 30, after fuse failures and relighting, the mine detonated with a massive roar, hurling earth, guns, and 300 Confederates skyward. The blast created a 170-foot crater, 30 feet deep. Ledlie’s division charged but milled in the crater, trapped by steep walls and debris. Confederate survivors, stunned but rallying, fired from the rims. Elliott’s South Carolina brigade held the flanks. Union troops, leaderless (Ledlie hid in a bombproof), clustered helplessly as Confederates under Mahone counterattacked by 8:00 AM, turning the breach into a killing ground.

The Assault Turns to Slaughter

8/ As Union divisions piled in, chaos reigned. Ferrero’s USCT troops advanced bravely but faced murderous crossfire in the crater. Hand-to-hand fighting erupted; Confederates bayoneted and shot down into the pit. By 9:30 AM, Mahone’s charge sealed the breach, capturing hundreds. Heat and thirst tormented the trapped; some Union soldiers surrendered, others fought to the death. The attack collapsed by 1:00 PM, with Grant calling it off. Casualties: 3,798 Union (504 dead, 1,881 wounded, 1,413 missing); 1,500 Confederate. The Crater became a symbol of mismanagement and horror.

8/ As Union divisions piled in, chaos reigned. Ferrero’s USCT troops advanced bravely but faced murderous crossfire in the crater. Hand-to-hand fighting erupted; Confederates bayoneted and shot down into the pit. By 9:30 AM, Mahone’s charge sealed the breach, capturing hundreds. Heat and thirst tormented the trapped; some Union soldiers surrendered, others fought to the death. The attack collapsed by 1:00 PM, with Grant calling it off. Casualties: 3,798 Union (504 dead, 1,881 wounded, 1,413 missing); 1,500 Confederate. The Crater became a symbol of mismanagement and horror.

Aftermath and Investigations

9/ The Battle of the Crater’s failure prolonged the siege, boosting Confederate morale while demoralizing Union troops. Grant lamented it as a “stupendous failure,” blaming poor execution. A court of inquiry faulted Burnside, Ledlie (drunk during battle), and Meade’s changes. Ledlie was dismissed; Burnside resigned. The siege dragged on, with Grant extending lines and raiding rails, like the August Weldon Railroad destruction. Petersburg fell April 2, 1865, after Lee’s lines broke, leading to Appomattox. The Crater’s toll underscored the war’s evolving savagery.

9/ The Battle of the Crater’s failure prolonged the siege, boosting Confederate morale while demoralizing Union troops. Grant lamented it as a “stupendous failure,” blaming poor execution. A court of inquiry faulted Burnside, Ledlie (drunk during battle), and Meade’s changes. Ledlie was dismissed; Burnside resigned. The siege dragged on, with Grant extending lines and raiding rails, like the August Weldon Railroad destruction. Petersburg fell April 2, 1865, after Lee’s lines broke, leading to Appomattox. The Crater’s toll underscored the war’s evolving savagery.

Conclusion

10/ The Siege of Petersburg and Battle of the Crater exemplified the Civil War’s shift to entrenched warfare, costing over 70,000 casualties in a brutal stalemate. Grant’s persistence wore down Lee, but the Crater’s explosion—meant for breakthrough—devolved into a massacre due to flawed leadership and plans. The July 30, 1864, debacle, with 5,300 casualties, highlighted innovation’s risks and human error. Petersburg’s fall sealed the Confederacy’s fate, ending the war within a week. This campaign’s grinding horror foreshadowed modern conflicts, a testament to endurance and sacrifice in America’s bloodiest chapter.

10/ The Siege of Petersburg and Battle of the Crater exemplified the Civil War’s shift to entrenched warfare, costing over 70,000 casualties in a brutal stalemate. Grant’s persistence wore down Lee, but the Crater’s explosion—meant for breakthrough—devolved into a massacre due to flawed leadership and plans. The July 30, 1864, debacle, with 5,300 casualties, highlighted innovation’s risks and human error. Petersburg’s fall sealed the Confederacy’s fate, ending the war within a week. This campaign’s grinding horror foreshadowed modern conflicts, a testament to endurance and sacrifice in America’s bloodiest chapter.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh