An update on the war following a recent trip. As Russian offensive presume mounts, the front is not at risk of collapse, though salients have formed. More concerning is that Russian improvements in drone employment have reduced Ukraine’s advantages. Long thread. 1/

In 2024 AFU expanded drone units within the force. This helped offset Russia’s materiel advantage, while compensating for the AFU’s continued manpower deficit. These initiatives are now well known and I covered them in previous threads. 2/

https://x.com/KofmanMichael/status/1902694940485767451

Drones became responsible for most day-to-day casualties at the front, attriting Russian forces at 0-15km, and serving as the main force multiplier for the AFU. This enabled a low-density defending force to hold the 1200km+ front line, establishing defeat and denial zones. 3/

Russian casualties increased relative to terrain being gained. However, it was unclear whether drones would be enough to stabilize the front line given Ukraine’s manpower challenges, RF ability to replace losses, and if Russian forces could adapt to counter this approach. 4/

Since then, the Russian military began deploying its own offensive ‘line of drones,’ and improving how it employs drone units. Russian Rubicon drone units have spread to every Russian grouping of troops, and are the most spoken of challenge across the front. 5/

Rubicon formations focus on severing logistics with fiber-optic drones operating 20-25km behind the front line, destroying drone positions, and intercepting Ukrainian drones (winged ISR/heavy multirotor). In general, Russian drone units have become better organized. 6/

This does not mean that Ukraine has lost its qualitative edge in drone employment, but that the advantage has narrowed, Russian forces continue to adapt, and Ukraine must find ways to stay ahead. 7/

The situation in Sumy has stabilized after AFU deployed air assault units there to counter the Russian advance, holding it to a small buffer of 200km2. Russian forces make slow progress by Kupiansk, and east of the Oskil river, but continue inching forward. 8/

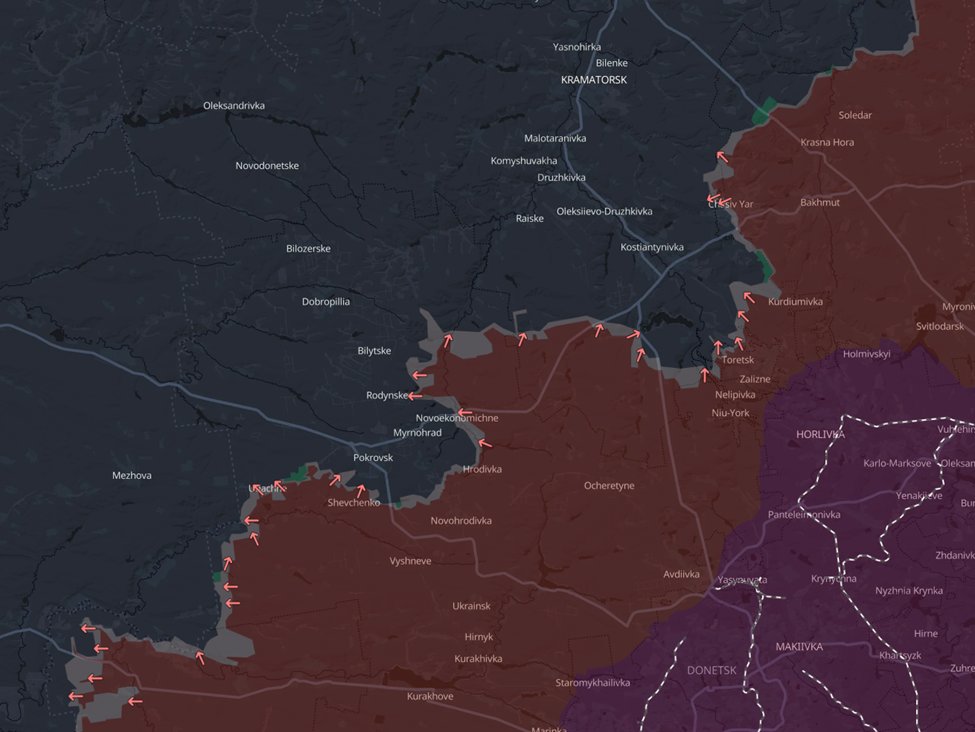

The immediate problem is the near envelopment of Pokrovsk, the pocket formed around Kostiantynivka, and the fighting near the Dnipro/Donetsk border by Novopavlivka. Russian units are also trying to stretch AFU manpower with attempts to push in Zap along the Dnipro river. 9/

The Russian military continues to underperform given their overall advantage in manpower and materiel. It is remarkable that AFU has held Pokrovsk and Chasiv Yar this long. But the situation has worsened, and probably will further before Russian offensives stall. 10/

The current dynamic is one of lines held by what are often 3-man positions with large gaps in between. These are neither firing positions, or observation points. They form a porous line in which infantry are often told to not to expose themselves unless absolutely necessary. 11/

Russian attacks are sometimes in 4-6 man groups, but in many cases have decreased to numerous 2-3 man sections trying to penetrate in between Ukrainian positions. Russian infantry seeks to advance as far as possible past Ukraine’s initial line and entrench there. 12/

Although many may be lost, some get through, and entrench awaiting reinforcements. Much the same can be said of motorcycle and buggy assaults, trying to bypass initial 'lines' and enter the rear. Most fail, but not all, leading to small tactical advances. 13/

Mechanized assaults are now seen much less frequently. In part because Russian forces are trying to conserve equipment, but also because AFU has long optimized for defeating traditional mechanized attacks which invariably fail with high vehicle losses. 14/

This is why evaluating armor availability as a metric is still useful, but less relevant if Russian forces are advancing at a faster rate than in 2024 with much lower use of AFVs. Similarly, artillery fire rate asymmetry was critical 2022-2023, but no longer as relevant. 15/

Although there is great work done detailing Ukrainian fortifications, most of the observed positions are constructed in the open and will never be occupied by units. They are easily targeted and destroyed. Ukraine lacks infantry to man most of them in the first place. 16/

This is not a war of trenches. It is a war of individual fighting positions, fortified and well masked units in tree lines, buildings, basements, or in dense forests. Occupying fortifications in the open is usually considered suicidal by troops. 17/

Since pervasive ISR and fires impose a degree of fire control over forward positions it is not possible to maintain large numbers of troops forward, sustain, or rotate them. Now some are on the line for 90+ days, and it often takes several days to reach a position on foot. 18/

Despite drones being the main casualty producing weapon (80%+), artillery remains important, with many units’ artillery use holding steady, or in some cases increasing. Artillery canalizes attacks, suppresses, operates in all-weather conditions, and is still relevant. 19/

Overemphasis on drones overlooks that the current dynamic is due to a combination of mining, use of drones, and traditional artillery fires. Hence maintaining adequate supply of arty and mortar munitions remains important despite drones doing much of the lifting. 20/

Russian tactics do not lend themselves to attaining operationally significant breakthroughs, but given the character of the fight, territory changing hands is a lagging indicator for what’s happening. Consequently, ‘gradually then suddenly’ transitions are possible. 21/

Ukrainian forces are increasingly defending in salients, with Russian drone units working to constrain logistical supply to these areas in an effort to collapse the pockets. Hence the geometry of the battlefield lends itself poorly to stabilization. 22/ (DeepStateMap)

The main culprit is a policy to hold onto every meter, even when in near envelopment, or in disadvantageous terrain. Rather than trading space for attrition, or conducting a mobile defense, AFU commanders are forced to try and hold onto untenable positions. 23/

Russian drone strikes have increasingly focused on bombarding civilian structures, and Ukraine’s defense industry in particular, seeking to suppress domestic production. Shahed (Geran) drones are also used against targets close to frontline positions. 24/

There has been an exponential increase in Russian drone & missile strikes against Ukrainian infrastructure. However, Ukraine is rapidly scaling up use of drone-based interceptors, paired with light radars. 25/

It will take time to expand production, upgrade mobile air defense, and build out a defensive line of air defense units, but the technical solution to the Shahed/imitator drone saturation problem exists and it is a matter of resourcing its deployment. 26/

Ukraine’s Unmanned Systems Forces are now led by Robert Brovdi, head of Madyar, and is launching plans that will better integrate and systematize drone employment. These hold promise as Ukrainian drone employment needs to evolve to stay ahead. 27/

One area where Ukraine remains clearly ahead of Russian forces is UGV employment for logistics, and medivac. This is more about establishing capable mesh networks to enable UGV use across terrain, and the cost of the comms can easily equal that of the platform. 28/

Ukraine is also seeking to close the gap in strike munitions that cover the 30-100km range, and strike systems for operational depths of 300km+ that are much more effective than cheap light drones, i.e. GLCMs and SRBMs. 29/

Ukraine is finally getting rid of the OTU and TG command layers that offered little besides trying to micromanage brigades, and set unrealistic combat tasks. Corps will take over, arranged under two Joint Task Forces (East and North) reporting to the OSUV. 30/

The new Corps hold promise, but the commands are being formed quickly. They will take time to become a cohesive structure, and unfortunately, they will have to command the units around them, not the those assigned to them, since BDEs can’t be easily redeployed. 31/

But it is not clear how much decision-making authority Corps, JTFs, or even OSUV commanders will have if the General Staff attempts to micromanage at the tactical level, retaining authority for allowing withdrawal from any positions, or order costly counterattacks. 32/

Russia continues to receive large volumes of artillery ammo from DPRK, and artillery systems, while being supported by China. Yet its economy is slowing down, and the increased rate of manpower losses has forced a postponement of force expansion plans in 2025. 33/

Bottom line: Despite the challenges, Ukrainian forces continue to hold Russian forces to incremental gains, extracting a steep price for territorial gains. Drone units are a key part of the solution, but by themselves may not be sufficient to stabilize the front. 34/

Ukraine needs a mix of hi-low capabilities (including expanding offensive strike), steady Western support & investment in its defense sector, alongside necessary reforms to force management, organization, and force generation. 35/

There's a fair amount I couldn't include in this thread as it was already 35 posts long, and I always ask myself how do we know what we know? Are we looking at the right things? Is there enough evidence for any given claim? If you've made it this far - thanks for reading.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh