American Legend: Daniel Boone

Politico says that Heritage Americans are obsessed with Daniel Boone, and you know what, they're right!

When's the last time you read about the life of this legendary American frontiersman? See more below!

Politico says that Heritage Americans are obsessed with Daniel Boone, and you know what, they're right!

When's the last time you read about the life of this legendary American frontiersman? See more below!

Early Life and Family (1734–1750s)

Daniel Boone was born on November 2, 1734, in a log cabin in Berks County, Pennsylvania, to a family of Quaker settlers. His father, Squire Boone, was a weaver and blacksmith, instilling in young Daniel a strong work ethic and practical skills. Growing up on the frontier, Boone learned to hunt and track game by age 12, becoming adept with a rifle.

His family’s move to North Carolina’s Yadkin Valley in 1750 exposed him to the rugged beauty of the American wilderness. This early immersion in frontier life shaped Boone’s love for exploration and self-reliance, qualities that would define his legacy. He married Rebecca Bryan in 1756, starting a family that grounded his adventurous spirit.

Daniel Boone was born on November 2, 1734, in a log cabin in Berks County, Pennsylvania, to a family of Quaker settlers. His father, Squire Boone, was a weaver and blacksmith, instilling in young Daniel a strong work ethic and practical skills. Growing up on the frontier, Boone learned to hunt and track game by age 12, becoming adept with a rifle.

His family’s move to North Carolina’s Yadkin Valley in 1750 exposed him to the rugged beauty of the American wilderness. This early immersion in frontier life shaped Boone’s love for exploration and self-reliance, qualities that would define his legacy. He married Rebecca Bryan in 1756, starting a family that grounded his adventurous spirit.

Exploration and Settlement of Kentucky (1760s–1770s)

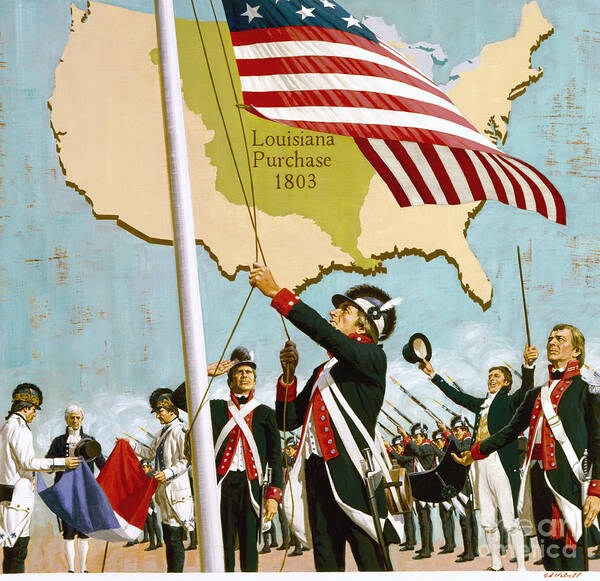

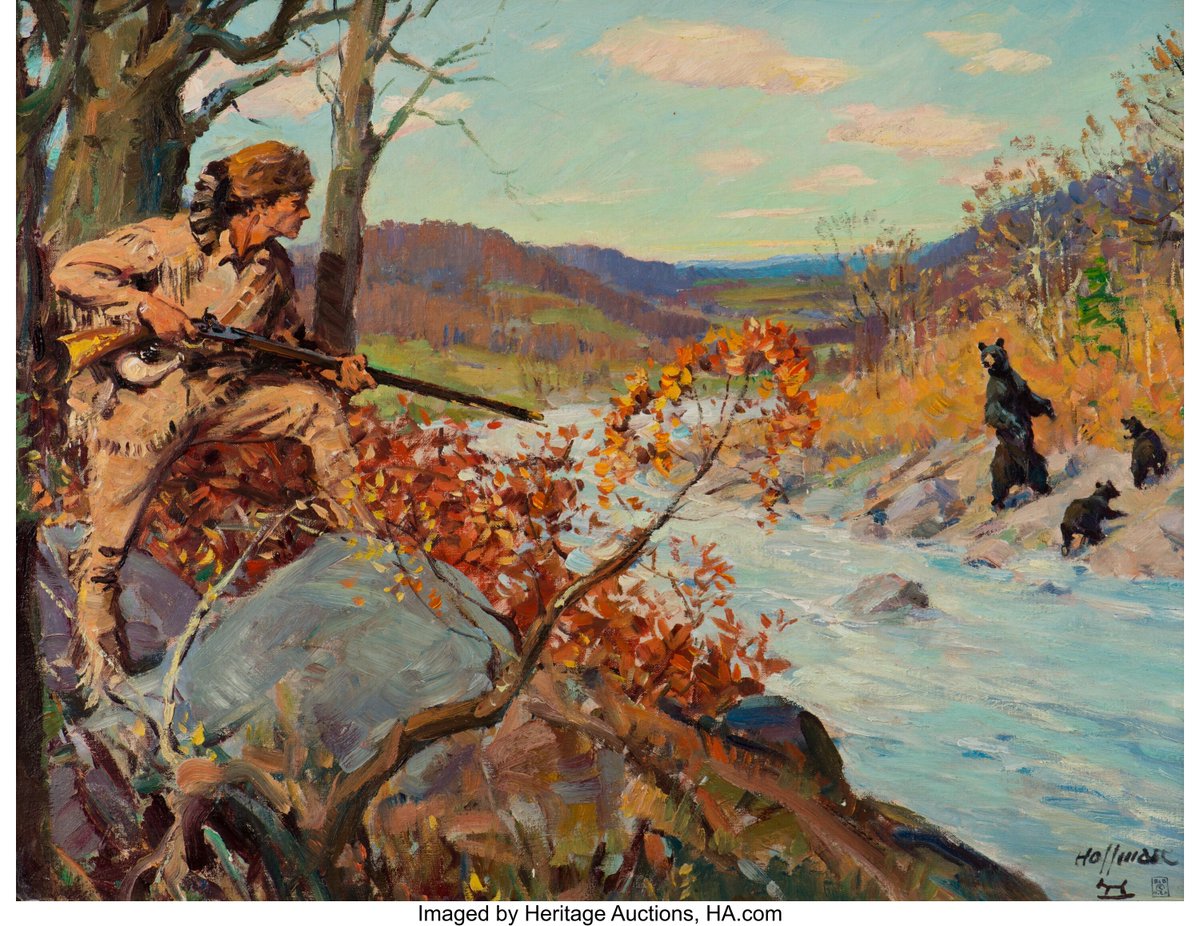

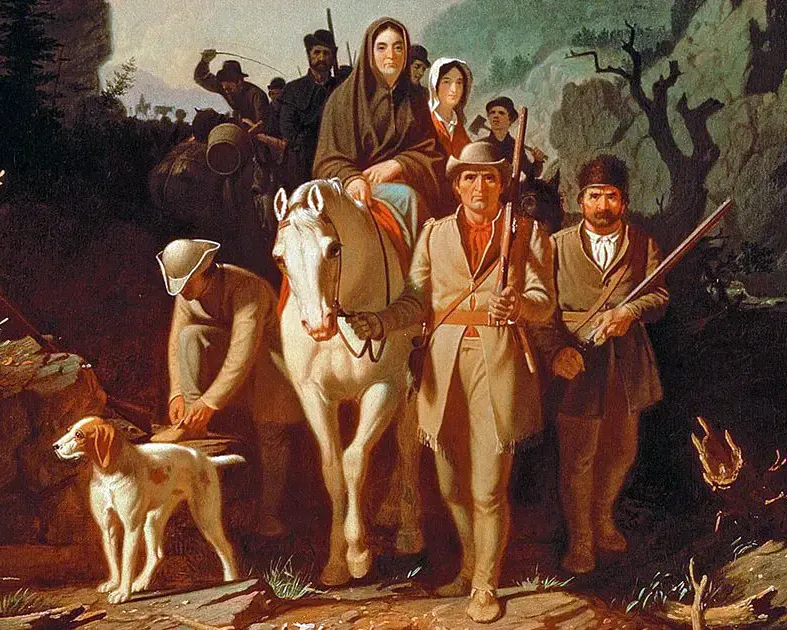

In the 1760s, Boone’s curiosity led him to explore the uncharted lands west of the Appalachian Mountains. His 1769 expedition through the Cumberland Gap, a natural pass in the mountains, opened a vital route to the fertile lands of Kentucky. Accompanied by fellow frontiersmen, Boone blazed the Wilderness Road, a path that enabled thousands of settlers to follow.

His keen knowledge of the terrain and ability to navigate Indian trails earned him respect among his peers. Boone’s explorations showcased American determination to expand westward, fulfilling the young nation’s vision of growth. His efforts laid the groundwork for future settlements in the Ohio River Valley.

In the 1760s, Boone’s curiosity led him to explore the uncharted lands west of the Appalachian Mountains. His 1769 expedition through the Cumberland Gap, a natural pass in the mountains, opened a vital route to the fertile lands of Kentucky. Accompanied by fellow frontiersmen, Boone blazed the Wilderness Road, a path that enabled thousands of settlers to follow.

His keen knowledge of the terrain and ability to navigate Indian trails earned him respect among his peers. Boone’s explorations showcased American determination to expand westward, fulfilling the young nation’s vision of growth. His efforts laid the groundwork for future settlements in the Ohio River Valley.

Settling Kentucky and Boonesborough

In 1775, Boone founded Boonesborough, one of the first American settlements in Kentucky, under the employ of the Transylvania Company. He brought his family and other settlers to the region, building a fortified community along the Kentucky River. Boone’s leadership helped the settlers endure harsh winters and Indian raids, fostering a spirit of cooperation.

His respectful dealings with local Indians, including the Shawnee, often aimed at peaceful coexistence through trade and negotiation. Boonesborough became a symbol of American resilience, attracting more pioneers to the frontier. Boone’s vision of a thriving Kentucky embodied the American dream of opportunity and prosperity.

In 1775, Boone founded Boonesborough, one of the first American settlements in Kentucky, under the employ of the Transylvania Company. He brought his family and other settlers to the region, building a fortified community along the Kentucky River. Boone’s leadership helped the settlers endure harsh winters and Indian raids, fostering a spirit of cooperation.

His respectful dealings with local Indians, including the Shawnee, often aimed at peaceful coexistence through trade and negotiation. Boonesborough became a symbol of American resilience, attracting more pioneers to the frontier. Boone’s vision of a thriving Kentucky embodied the American dream of opportunity and prosperity.

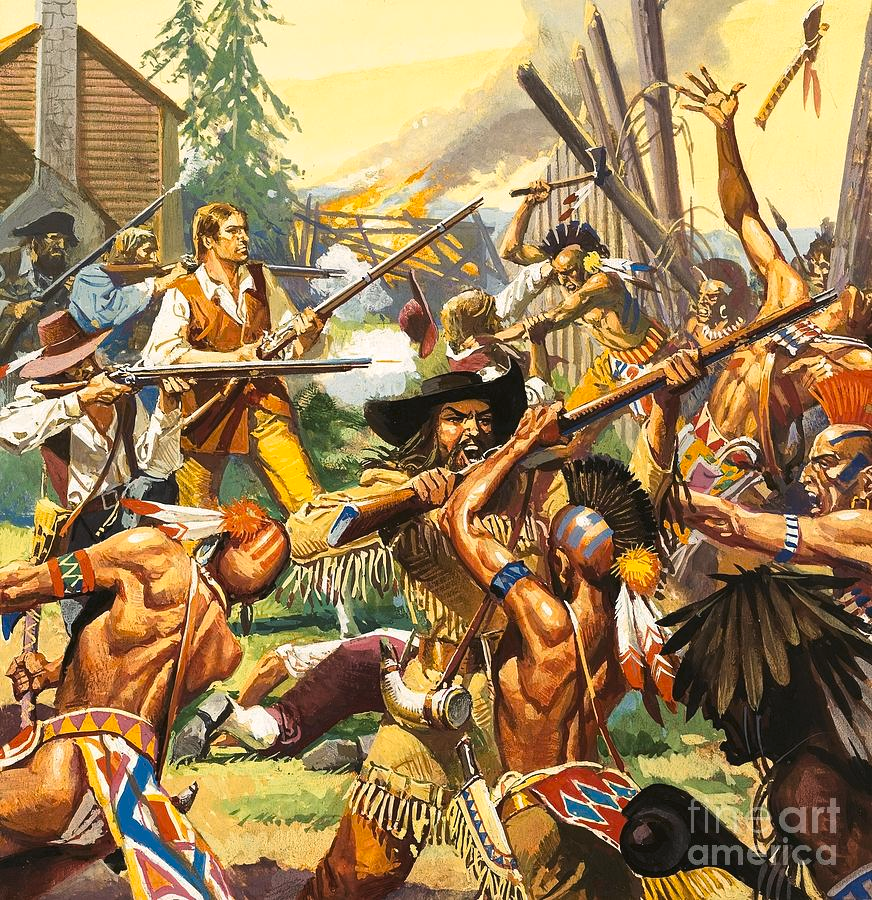

Adventures and Indian Encounters

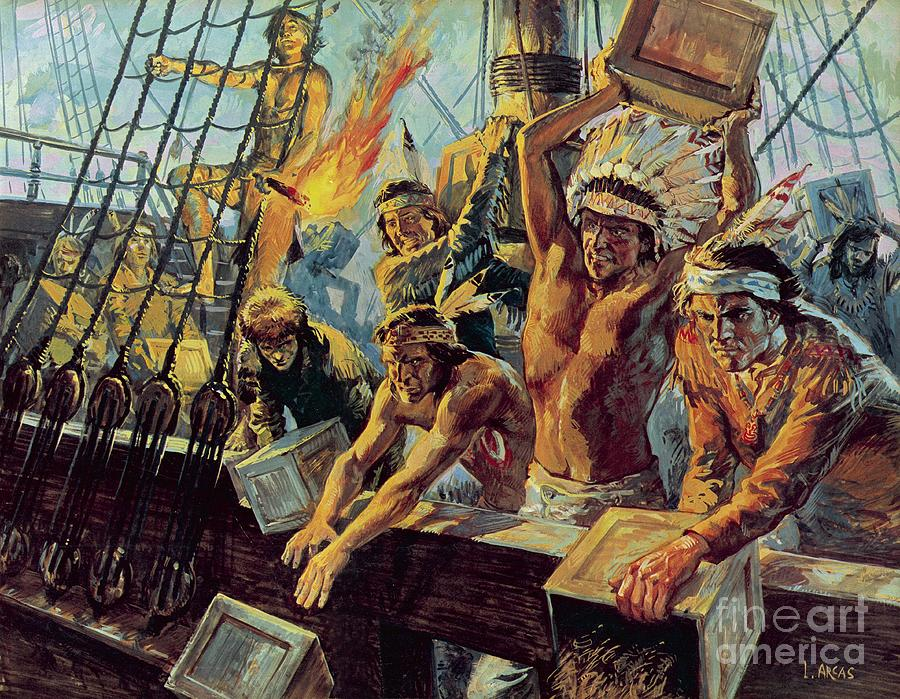

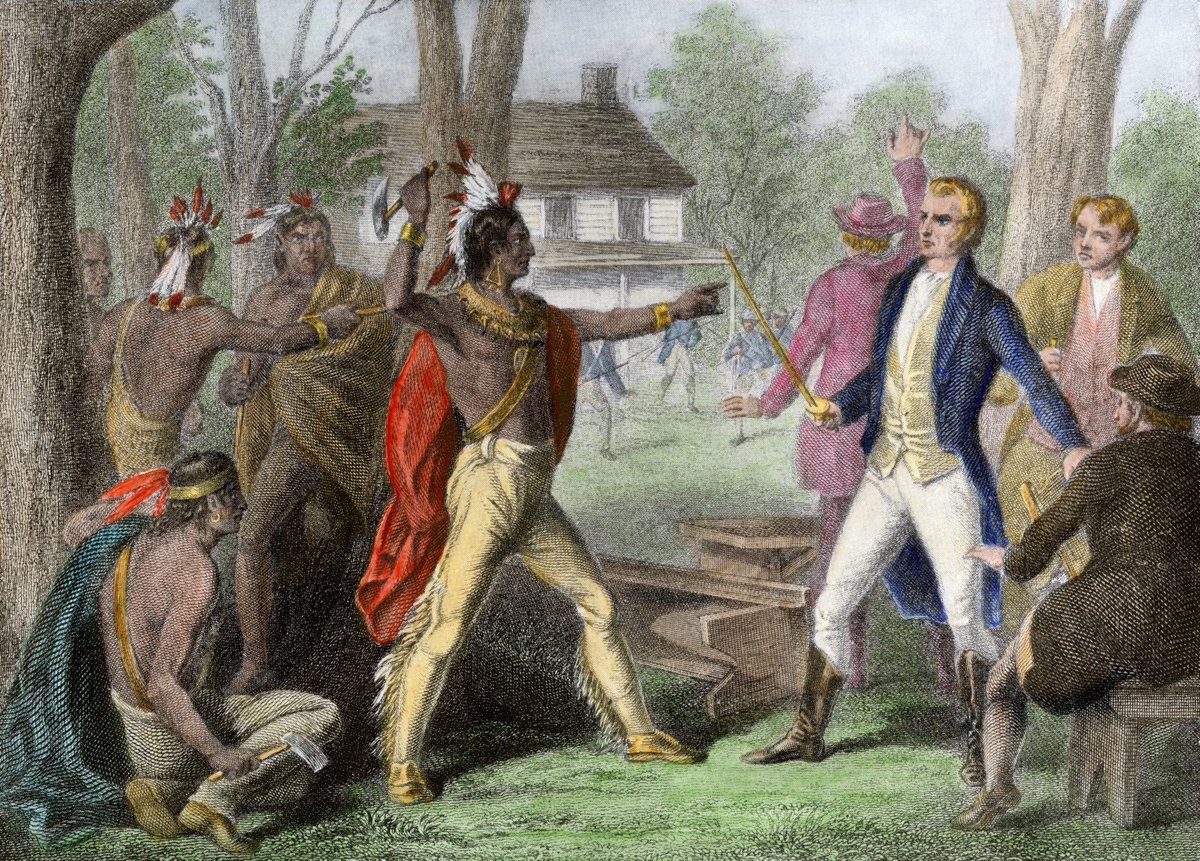

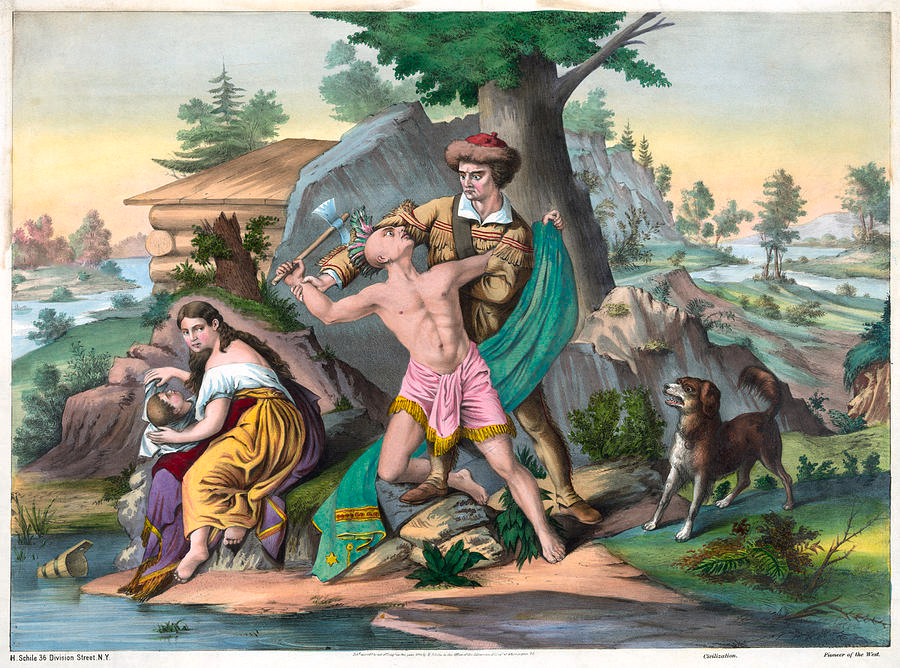

Boone’s life was marked by daring encounters, including his capture by Shawnee warriors in 1778 while gathering salt. Adopted into the tribe, he earned their admiration for his skills and courage before escaping to warn Boonesborough of an impending attack. His ability to understand Indian customs helped him navigate tense situations, often preventing bloodshed.

Boone’s exploits, like rescuing his daughter Jemima from Indian captors in 1776, became legendary, showcasing his bravery and devotion to family. These stories inspired Americans, portraying Boone as a hero who bridged the gap between cultures. His adventures reinforced the narrative of American grit in the face of wilderness challenges.

Boone’s life was marked by daring encounters, including his capture by Shawnee warriors in 1778 while gathering salt. Adopted into the tribe, he earned their admiration for his skills and courage before escaping to warn Boonesborough of an impending attack. His ability to understand Indian customs helped him navigate tense situations, often preventing bloodshed.

Boone’s exploits, like rescuing his daughter Jemima from Indian captors in 1776, became legendary, showcasing his bravery and devotion to family. These stories inspired Americans, portraying Boone as a hero who bridged the gap between cultures. His adventures reinforced the narrative of American grit in the face of wilderness challenges.

Later Years and Legacy

After Kentucky, Boone moved to Missouri in 1799, seeking new opportunities as the frontier shifted westward. Granted land by the Spanish government, he continued hunting and trapping into his later years, embodying the independent spirit of the American pioneer. Despite financial struggles and land disputes, Boone remained a beloved figure, his tales spread through books and folklore.

He died peacefully on September 26, 1820, in Missouri, leaving behind a legacy of exploration and settlement. Boone’s life inspired generations, symbolizing the courage and ambition that built America. His contributions to opening the West remain a proud chapter in the nation’s history.

After Kentucky, Boone moved to Missouri in 1799, seeking new opportunities as the frontier shifted westward. Granted land by the Spanish government, he continued hunting and trapping into his later years, embodying the independent spirit of the American pioneer. Despite financial struggles and land disputes, Boone remained a beloved figure, his tales spread through books and folklore.

He died peacefully on September 26, 1820, in Missouri, leaving behind a legacy of exploration and settlement. Boone’s life inspired generations, symbolizing the courage and ambition that built America. His contributions to opening the West remain a proud chapter in the nation’s history.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh