Canada’s renewed focus on Arctic security has led to lots of comparisons with Russia’s Arctic posture - usually to Canada’s disadvantage.

But these comparisons tend to ignore some key realities. I want to break some of that down. 🧵

But these comparisons tend to ignore some key realities. I want to break some of that down. 🧵

Canada and Russia have fundamentally different relationships with the Arctic.

That’s because of three primary factors:

- Physical geography

- Proximity to economic centres

- Strategic alternatives

That’s because of three primary factors:

- Physical geography

- Proximity to economic centres

- Strategic alternatives

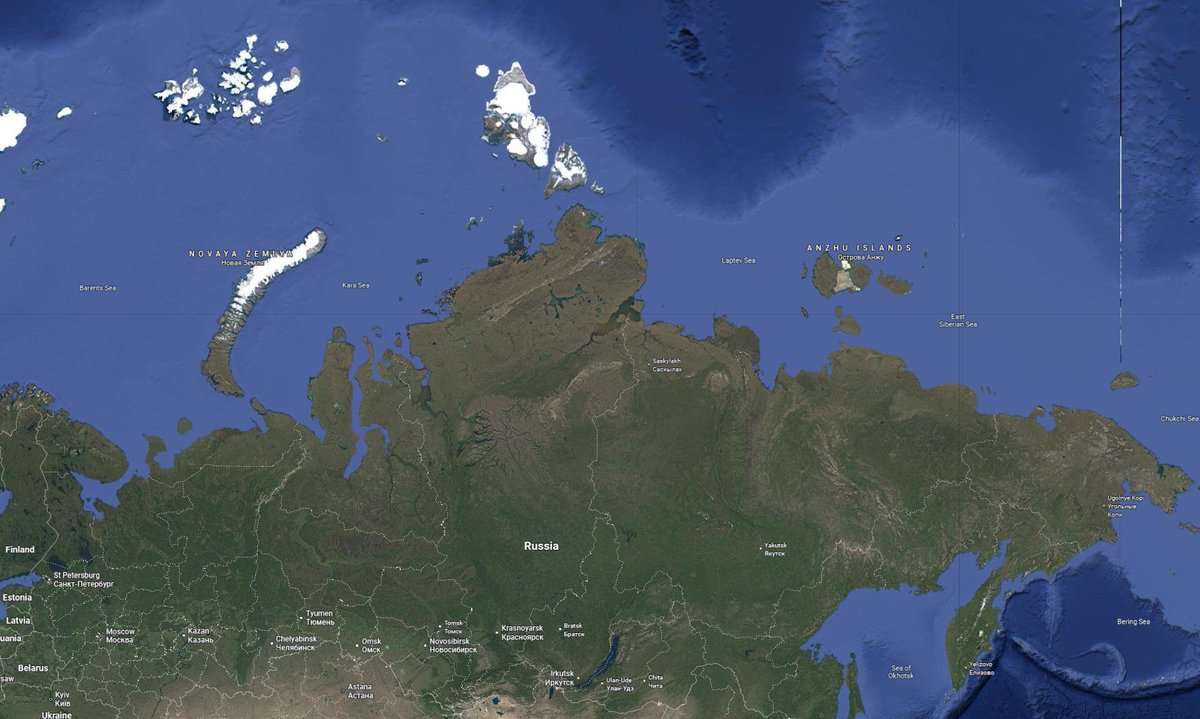

First, the Arctic’s physical geography.

North of Canada’s main landmass is a dense archipelago - nearly 100 large islands (and thousands of small ones) with narrow channels in between.

Russia’s Arctic is mostly a single, contiguous, coastline with a few scattered islands.

North of Canada’s main landmass is a dense archipelago - nearly 100 large islands (and thousands of small ones) with narrow channels in between.

Russia’s Arctic is mostly a single, contiguous, coastline with a few scattered islands.

In warm waters, barrier islands are a benefit - creating sheltered routes for ships.

In the Arctic? They trap ice.

Sea ice around Canada piles into massive ridges in winter - impassable to even the heaviest icebreakers - and lingers longer into summer.

In the Arctic? They trap ice.

Sea ice around Canada piles into massive ridges in winter - impassable to even the heaviest icebreakers - and lingers longer into summer.

The result is that Russia has a longer natural Arctic shipping season into, out of, and through its Arctic regions than Canada does. And it’s easier for them to extend this season through the use of icebreakers, making some routes viable year-round.

This difference in shipping seasons matters.

Sea shipping is by far the lowest cost way to move goods. It’s hard to be economically competitive without it.

So easier Arctic shipping means more trade, and more trade drives development.

Sea shipping is by far the lowest cost way to move goods. It’s hard to be economically competitive without it.

So easier Arctic shipping means more trade, and more trade drives development.

The second key difference is how accessible the Arctic is from each country’s economic centre.

Russia’s main economic centres - Moscow and St. Petersburg, with a combined population of ~18 million - are both under 1,300km from Arctic-facing ports like Severodvinsk.

Russia’s main economic centres - Moscow and St. Petersburg, with a combined population of ~18 million - are both under 1,300km from Arctic-facing ports like Severodvinsk.

Canada by contrast has one “Arctic” port: Churchill.

But its closest major city, also ~1300km away, is Winnipeg (Pop. ~800k), and Churchill is still 1,000km from the Arctic Circle.

To get truly Arctic you’re looking at Tuktoyaktuk. Closest city of size? Whitehorse (Pop. ~30k).

But its closest major city, also ~1300km away, is Winnipeg (Pop. ~800k), and Churchill is still 1,000km from the Arctic Circle.

To get truly Arctic you’re looking at Tuktoyaktuk. Closest city of size? Whitehorse (Pop. ~30k).

What this means is that Russia can move goods from its economic heartland into the Arctic more easily and more cheaply.

And thanks to better shipping conditions, those goods can actually go somewhere - whether to other parts of Russia’s Arctic or to be traded with other nations.

And thanks to better shipping conditions, those goods can actually go somewhere - whether to other parts of Russia’s Arctic or to be traded with other nations.

The third difference can be easy to overlook, but is at least as important as the first two:

Strategic alternatives.

Canada has other options. Russia does not.

Strategic alternatives.

Canada has other options. Russia does not.

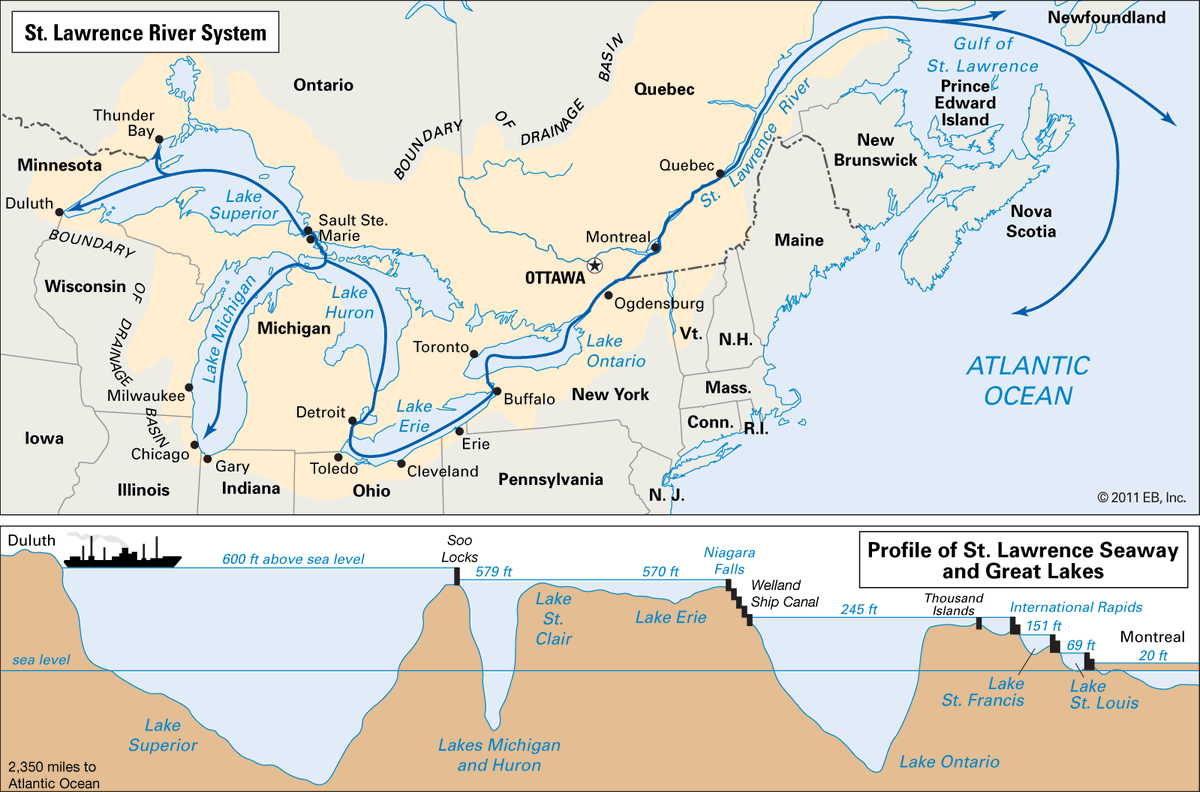

Canada is blessed with some of the best natural, ice-free, harbours in the world on both its East and West coasts. Vancouver, Halifax, Prince Rupert and Saint John are all contenders to be among the 10 best natural harbours anywhere - all opening directly into the High Seas.

Canada also has the Great Lakes–St. Lawrence Seaway: not ice-free, but is the farthest inland navigable waterway on Earth, and cuts through Canada’s industrial heartland on its way to vast interior resources.

Bottom line: Canada doesn’t need to ship through the Arctic.

Bottom line: Canada doesn’t need to ship through the Arctic.

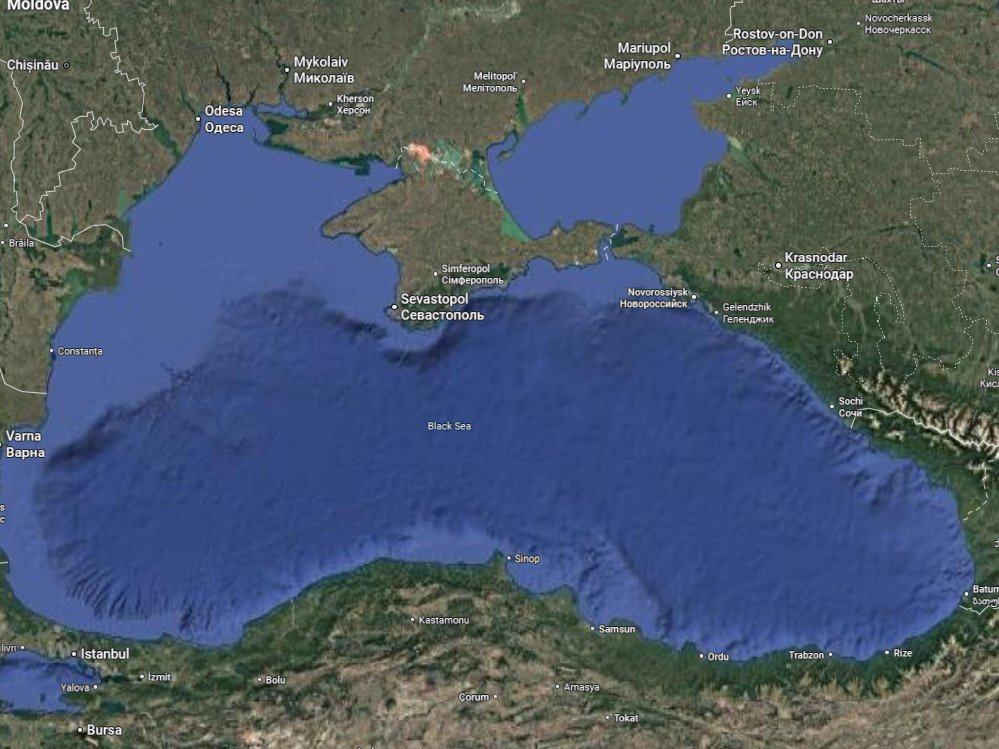

Russia’s situation is very different.

Russia’s best Western ports—St. Petersburg and Novorossiysk—are stuck in inland seas (the Baltic and Black seas, respectively), bottlenecked by potentially unfriendly powers.

Russia’s best Western ports—St. Petersburg and Novorossiysk—are stuck in inland seas (the Baltic and Black seas, respectively), bottlenecked by potentially unfriendly powers.

Meanwhile, Russia’s Eastern ports are thousands of kilometers from where most industry is and, even then, connect to the Sea of Japan - the exits from which are controlled by another potentially unfriendly power.

That leaves only the Arctic as an unthreatened route.

That leaves only the Arctic as an unthreatened route.

What this difference in other strategic options means is that the two countries don’t need access to the Arctic in the same ways.

For Canada, Arctic access is valuable.

For Russia, Arctic access is existential.

For Canada, Arctic access is valuable.

For Russia, Arctic access is existential.

This leads to differences in how the two countries invest in the Arctic.

For example: Canada is often criticized for not “keeping up” with Russia’s icebreaker fleet.

But the incentives justifying Russia’s fleet - both economic and strategic - simply don’t exist for Canada.

For example: Canada is often criticized for not “keeping up” with Russia’s icebreaker fleet.

But the incentives justifying Russia’s fleet - both economic and strategic - simply don’t exist for Canada.

Similarly, Canada is sometimes criticized for not investing in nuclear powered icebreakers as Russia does.

However, Russia’s geography requires its icebreakers to remain in the Arctic year-round, where keeping them fueled is logistically difficult and expensive.

However, Russia’s geography requires its icebreakers to remain in the Arctic year-round, where keeping them fueled is logistically difficult and expensive.

Canada, meanwhile, mostly needs icebreakers in the Arctic when they can plausibly facilitate shipping - when other ships are able to operate there. This means Canada’s icebreakers travel back and forth between the Arctic and ice-free ports and tend to winter farther South.

Similar logic applies to Russia’s greater investment in Arctic military facilities, and industry.

But, again, that reflects necessity - not, necessarily, advantage.

But this doesn’t just cut one way.

But, again, that reflects necessity - not, necessarily, advantage.

But this doesn’t just cut one way.

Canada’s in-construction pair of Polar-class icebreakers will exceed the ice-breaking capability of any ship Russia operates—including its nuclear-powered icebreakers.

Why?

Because Canada faces thicker, harder ice, closer to home more often.

That’s Canada’s necessity.

Why?

Because Canada faces thicker, harder ice, closer to home more often.

That’s Canada’s necessity.

The crux of this is that when we compare Canada to Russia in the Arctic - militarily, economically, logistically - we need to remember:

They’re not playing the same game.

And they don’t need the Arctic in the same way.

They’re not playing the same game.

And they don’t need the Arctic in the same way.

Canada's Arctic policies shouldn't copy Russia's. They should reflect its own geography, economy, and strategic needs.

Different challenges. Different opportunities. Different countries.

/fin

Different challenges. Different opportunities. Different countries.

/fin

Thanks for reading this thread!

I enjoy writing long threads about interesting topics - but part of the satisfaction that makes me do it is seeing them read.

If you found value in this thread, could you go back to the top and like/share the lead post?

I enjoy writing long threads about interesting topics - but part of the satisfaction that makes me do it is seeing them read.

If you found value in this thread, could you go back to the top and like/share the lead post?

https://x.com/CDNPolicyHawk/status/1951412230701945291

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh