General George S. Patton, Old Blood and Guts 🧵

1/ General George S. Patton, known as “Old Blood and Guts,” remains a polarizing figure in American military history, celebrated for his brilliant armored tactics in World War II yet criticized for his reckless temperament and controversial actions. His relentless drive shaped Allied victories. Join me in exploring his life of audacity and command—a story of unparalleled valor and enduring debate.

1/ General George S. Patton, known as “Old Blood and Guts,” remains a polarizing figure in American military history, celebrated for his brilliant armored tactics in World War II yet criticized for his reckless temperament and controversial actions. His relentless drive shaped Allied victories. Join me in exploring his life of audacity and command—a story of unparalleled valor and enduring debate.

Early Life

2/ George Smith Patton Jr. was born on November 11, 1885, in San Gabriel, California, to a wealthy family with a storied military heritage. His father, George Smith Patton Sr., a lawyer, and his mother, Ruth Wilson Patton, raised him on a ranch, immersing him in tales of ancestral heroism. Despite struggling with dyslexia, Patton excelled in athletics and history, attending Virginia Military Institute before graduating from West Point in 1909, his ambition forging a path to leadership.

2/ George Smith Patton Jr. was born on November 11, 1885, in San Gabriel, California, to a wealthy family with a storied military heritage. His father, George Smith Patton Sr., a lawyer, and his mother, Ruth Wilson Patton, raised him on a ranch, immersing him in tales of ancestral heroism. Despite struggling with dyslexia, Patton excelled in athletics and history, attending Virginia Military Institute before graduating from West Point in 1909, his ambition forging a path to leadership.

Early Military Career

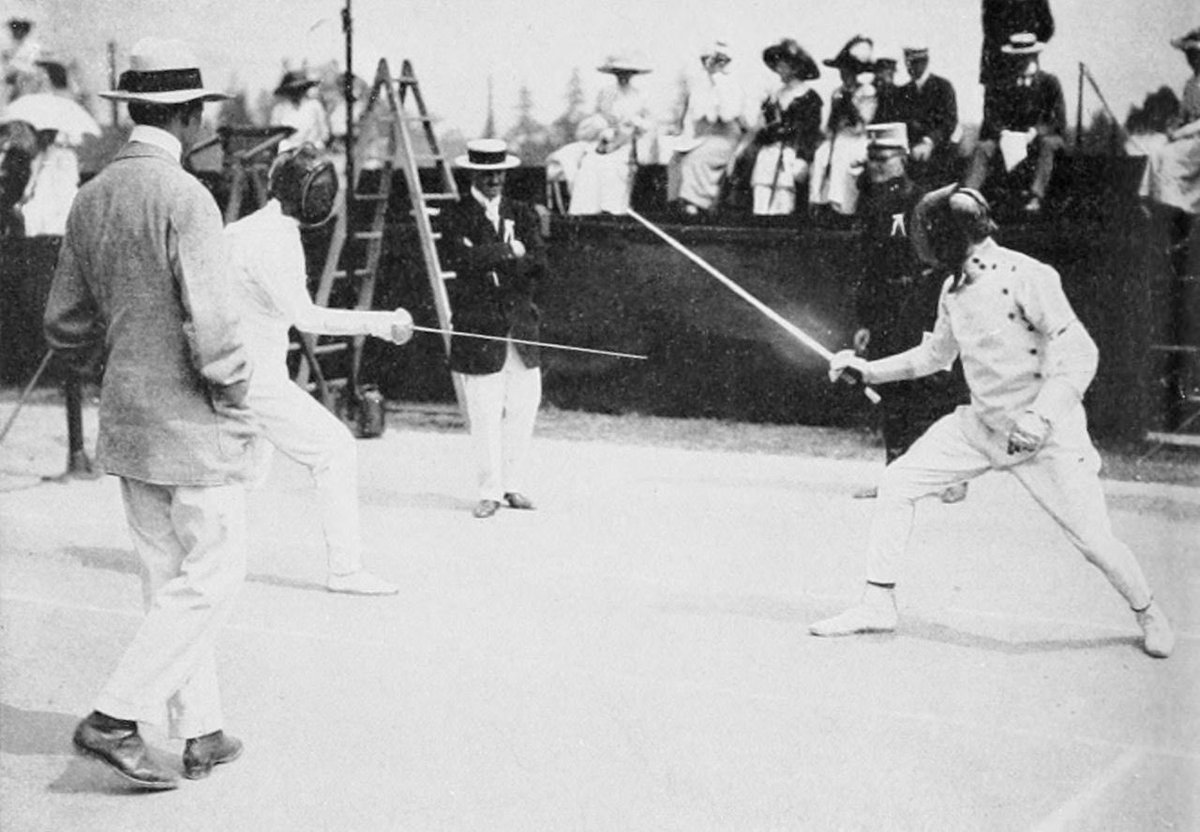

3/ Commissioned as a second lieutenant in the 15th Cavalry in 1909, Patton distinguished himself through exceptional horsemanship, competing in the 1912 Stockholm Olympics pentathlon, where he placed fifth. Stationed on the Mexican border, he joined General John J. Pershing’s Punitive Expedition in 1916, leading the first U.S. motorized attack and killing two of Pancho Villa’s lieutenants. Promoted to captain, his bold actions marked him as a rising star.

3/ Commissioned as a second lieutenant in the 15th Cavalry in 1909, Patton distinguished himself through exceptional horsemanship, competing in the 1912 Stockholm Olympics pentathlon, where he placed fifth. Stationed on the Mexican border, he joined General John J. Pershing’s Punitive Expedition in 1916, leading the first U.S. motorized attack and killing two of Pancho Villa’s lieutenants. Promoted to captain, his bold actions marked him as a rising star.

World War I

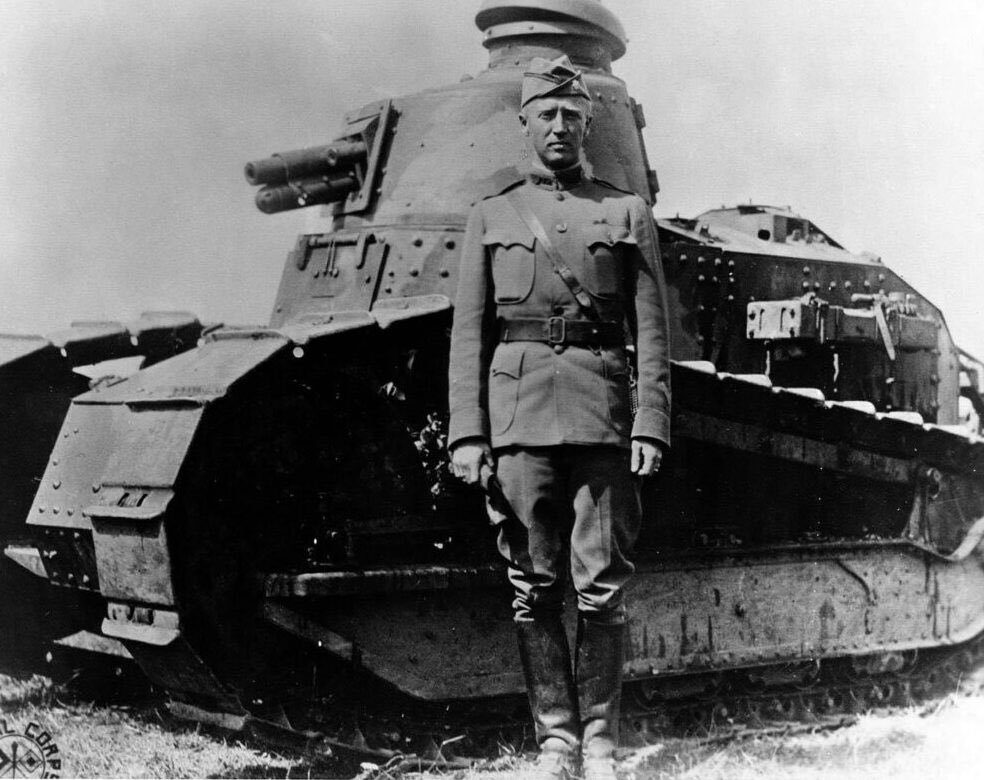

4/ In 1917, Patton deployed to France as an aide to Pershing but sought combat, taking command of the U.S. Tank Corps. He trained crews and led America’s first tank assault at Saint-Mihiel in September 1918, demonstrating innovative armored tactics. Wounded during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, he earned the Distinguished Service Cross and a Purple Heart. His wartime experience solidified his vision for mechanized warfare, earning him a promotion to colonel.

4/ In 1917, Patton deployed to France as an aide to Pershing but sought combat, taking command of the U.S. Tank Corps. He trained crews and led America’s first tank assault at Saint-Mihiel in September 1918, demonstrating innovative armored tactics. Wounded during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, he earned the Distinguished Service Cross and a Purple Heart. His wartime experience solidified his vision for mechanized warfare, earning him a promotion to colonel.

Interwar Period

5/ Reduced to captain after World War I, Patton tirelessly advocated for tank development, commanding cavalry units at Fort Myer and studying at the Army War College. Promoted to major in 1923 and lieutenant colonel in 1934, he controversially led troops dispersing the Bonus Army in Washington, D.C., in 1932. His writings on armored tactics influenced military doctrine, though peacetime frustrations fueled his fiery temperament.

5/ Reduced to captain after World War I, Patton tirelessly advocated for tank development, commanding cavalry units at Fort Myer and studying at the Army War College. Promoted to major in 1923 and lieutenant colonel in 1934, he controversially led troops dispersing the Bonus Army in Washington, D.C., in 1932. His writings on armored tactics influenced military doctrine, though peacetime frustrations fueled his fiery temperament.

World War II: Early Campaigns

6/ Recalled in 1940 as a colonel, Patton organized the 2nd Armored Division, earning promotion to major general. In Operation Torch of November 1942, he commanded the Western Task Force, capturing Casablanca in North Africa. Taking over II Corps after the Kasserine Pass defeat in February 1943, he restored discipline with strict measures, preparing troops for the successful Sicily invasion in July 1943.

6/ Recalled in 1940 as a colonel, Patton organized the 2nd Armored Division, earning promotion to major general. In Operation Torch of November 1942, he commanded the Western Task Force, capturing Casablanca in North Africa. Taking over II Corps after the Kasserine Pass defeat in February 1943, he restored discipline with strict measures, preparing troops for the successful Sicily invasion in July 1943.

World War II: Later Campaigns

7/ After slapping soldiers for “shell shock” in Sicily, Patton was sidelined but reinstated by Eisenhower for Normandy in 1944. Leading the Third Army, he executed a lightning advance across France, liberating thousands of towns and relieving Bastogne during the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944. Crossing the Rhine in March 1945, his forces reached Czechoslovakia, cementing his reputation for audacious armored warfare.

7/ After slapping soldiers for “shell shock” in Sicily, Patton was sidelined but reinstated by Eisenhower for Normandy in 1944. Leading the Third Army, he executed a lightning advance across France, liberating thousands of towns and relieving Bastogne during the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944. Crossing the Rhine in March 1945, his forces reached Czechoslovakia, cementing his reputation for audacious armored warfare.

Post-War

8/ Appointed military governor of Bavaria in 1945, Patton oversaw denazification but stirred controversy with outspoken criticism of Allied policies and comparisons of Nazis to American political parties. Relieved of command, he was reassigned to the Fifteenth Army for historical studies. His strong anti-Soviet stance reflected his belief in preparing for future conflicts, though his tenure was cut short by tragedy.

8/ Appointed military governor of Bavaria in 1945, Patton oversaw denazification but stirred controversy with outspoken criticism of Allied policies and comparisons of Nazis to American political parties. Relieved of command, he was reassigned to the Fifteenth Army for historical studies. His strong anti-Soviet stance reflected his belief in preparing for future conflicts, though his tenure was cut short by tragedy.

Death & Legacy

9/ On December 9, 1945, Patton suffered severe injuries in a car accident near Mannheim, Germany, paralyzing him from the neck down. He died twelve days later on December 21, 1945, at age 60 in Heidelberg, and was buried in Luxembourg American Cemetery. Patton’s legacy as a tactical genius endures, with his Third Army’s rapid campaigns celebrated in the 1970 film Patton and the Patton Museum. Admired for his victories, criticized for his temperament, he inspires debate on bold leadership.

9/ On December 9, 1945, Patton suffered severe injuries in a car accident near Mannheim, Germany, paralyzing him from the neck down. He died twelve days later on December 21, 1945, at age 60 in Heidelberg, and was buried in Luxembourg American Cemetery. Patton’s legacy as a tactical genius endures, with his Third Army’s rapid campaigns celebrated in the 1970 film Patton and the Patton Museum. Admired for his victories, criticized for his temperament, he inspires debate on bold leadership.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh