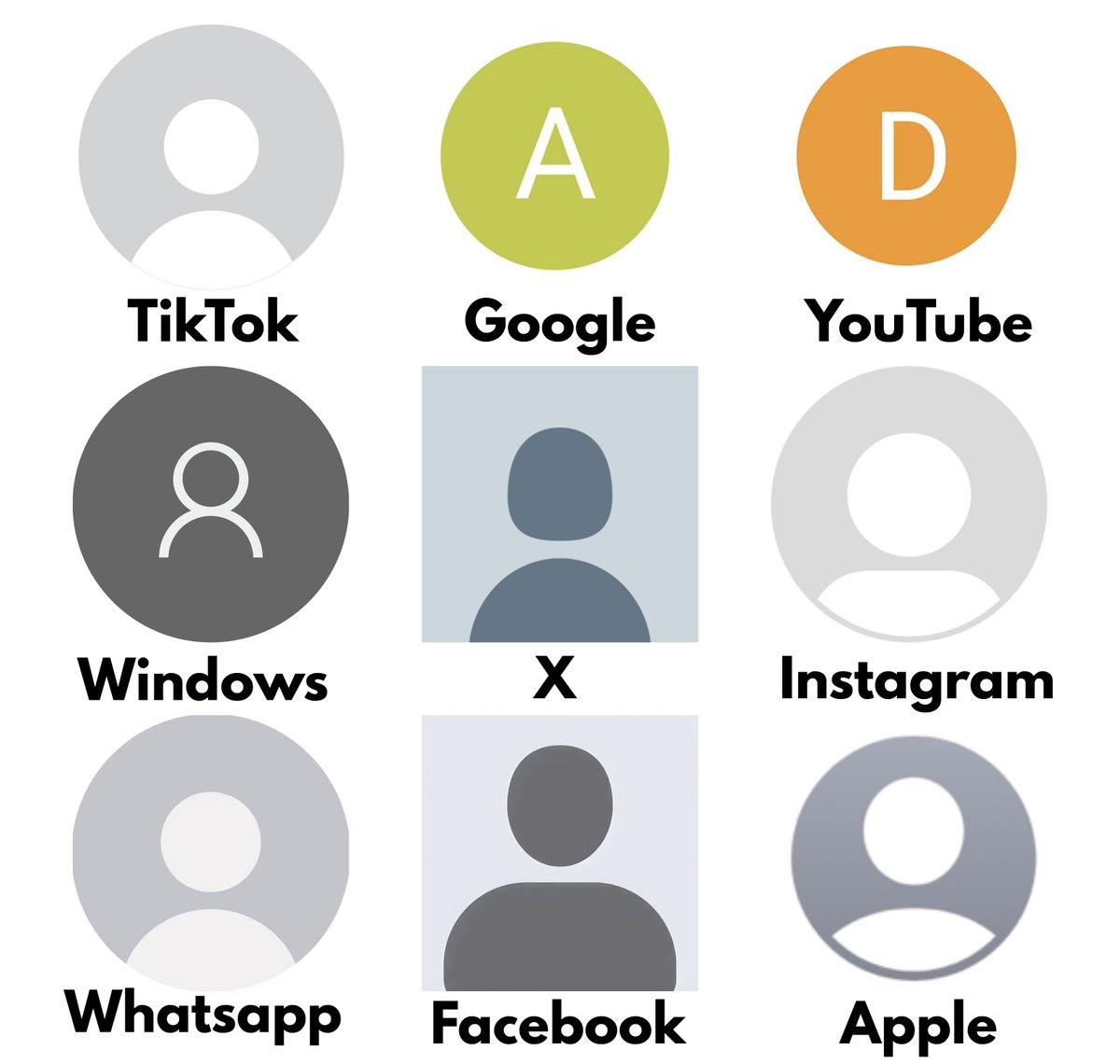

If one thing sums up the 21st century it's got to be all these default profile pictures.

You've seen them literally thousands of times, but they're completely generic and interchangeable.

Future historians will use them to symbolise our current era, and here's why...

You've seen them literally thousands of times, but they're completely generic and interchangeable.

Future historians will use them to symbolise our current era, and here's why...

To understand what any society truly believed, and how they felt about humankind, you need to look at what they created rather than what they said.

Just as actions instead of words reveal who a person really is, art always tells you what a society was actually like.

Just as actions instead of words reveal who a person really is, art always tells you what a society was actually like.

And this is particularly true of how they depicted human beings — how we portray ourselves.

That the Pharaohs were of supreme power, and were worshipped as gods far above ordinary people, is made obvious by the sheer size and abundance of the statues made in their name:

That the Pharaohs were of supreme power, and were worshipped as gods far above ordinary people, is made obvious by the sheer size and abundance of the statues made in their name:

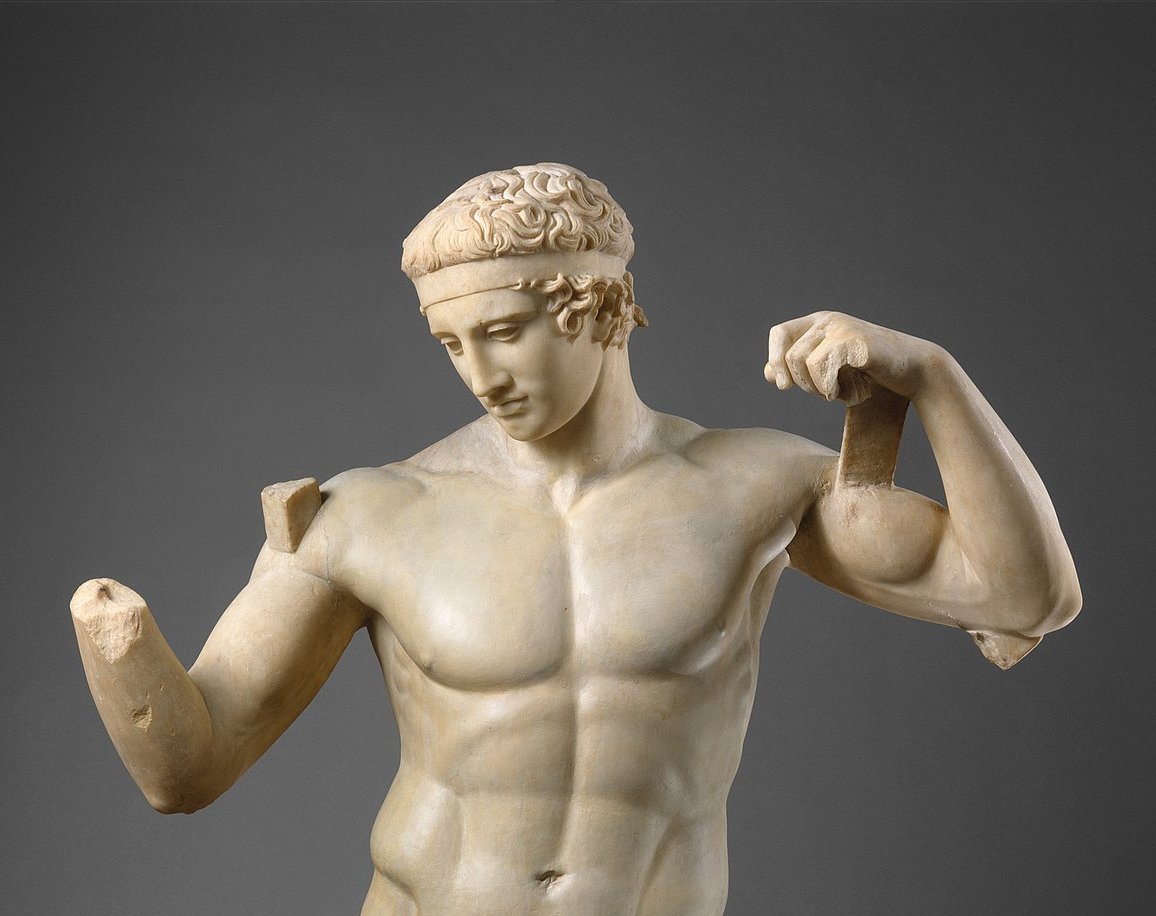

In Ancient Greece, meanwhile, those famous marble statues make it clear that the Greeks had an idealised view of humanity.

They believed in our intellectual and spiritual potential, even seemed to worship it, and put generically idealised humans on a level with the divine.

They believed in our intellectual and spiritual potential, even seemed to worship it, and put generically idealised humans on a level with the divine.

And that belief was mirrored in Ancient Greek literature, architecture, and philosophy.

Little wonder that Athens, where ideas of democracy — and therefore a belief in general human potential — first emerged, was also where lifelike-but-idealised statues like these were made.

Little wonder that Athens, where ideas of democracy — and therefore a belief in general human potential — first emerged, was also where lifelike-but-idealised statues like these were made.

The Roman Republic, by comparison, seemed to believe in something more like "ideal ugliness".

They thought of themselves as honest, hard-working, simple, patriotic people — and this belief, accurate or not, was reflected in their more rugged, consciously inelegant statuary:

They thought of themselves as honest, hard-working, simple, patriotic people — and this belief, accurate or not, was reflected in their more rugged, consciously inelegant statuary:

During the Middle Ages we had a somewhat different view.

It's easy to laugh at Medieval art and call it "bad"... but that was kind of the point.

Medieval people were waiting for Judgement Day, and so they didn't think too highly or pompously of humankind.

It's easy to laugh at Medieval art and call it "bad"... but that was kind of the point.

Medieval people were waiting for Judgement Day, and so they didn't think too highly or pompously of humankind.

You can see this in Medieval architecture.

Their willingness to accept our humbler nature, our imperfections, gave rise to those famous Gothic cathedrals where the beautiful and ugly, sacred and profane, were mixed together in buildings of immense scale and imaginative scope.

Their willingness to accept our humbler nature, our imperfections, gave rise to those famous Gothic cathedrals where the beautiful and ugly, sacred and profane, were mixed together in buildings of immense scale and imaginative scope.

During the Renaissance, however, the ancient view of humanity was revived — and art changed accordingly.

Michelangelo's David epitomises this shifting worldview; humankind was triumphant again, portrayed as strong, intelligent, and glorious.

More idealised... but also colder.

Michelangelo's David epitomises this shifting worldview; humankind was triumphant again, portrayed as strong, intelligent, and glorious.

More idealised... but also colder.

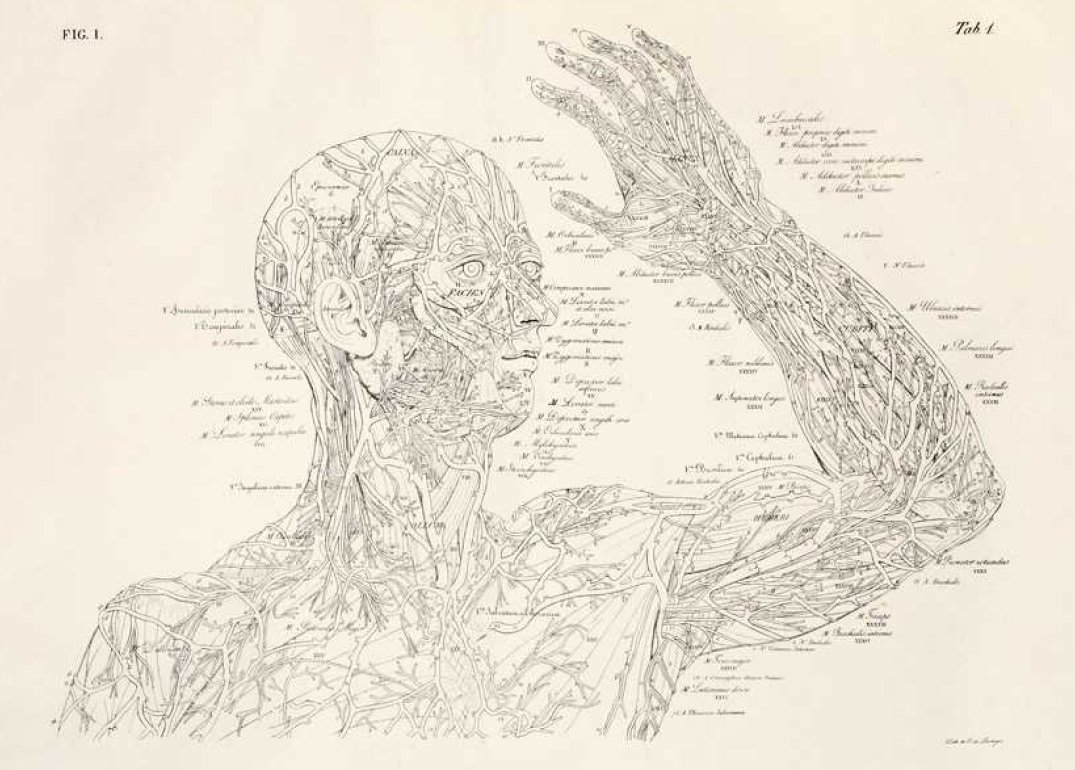

With the Scientific Revolution and Enlightenment, this changed once more.

For the first time in history we see proper, scientific, anatomical depictions of humankind.

Useful, accurate, and impressive... but without any sense of mystery, drama, or spirit.

For the first time in history we see proper, scientific, anatomical depictions of humankind.

Useful, accurate, and impressive... but without any sense of mystery, drama, or spirit.

And this mixture of sophistication with emptiness of spirit was matched in the vapid, ostentatious art of the 18th century.

An increasingly materialistic society lost faith in the idea of human genuineness — 18th century art, like 18th century literature, was awfully cynical.

An increasingly materialistic society lost faith in the idea of human genuineness — 18th century art, like 18th century literature, was awfully cynical.

It was against this cold, scientific view of humankind that Romanticism reacted.

In the art of somebody like Caspar David Friedrich or John Martin we see humans dwarfed by the might and sublimity of nature.

Mystery and emotion — despair, love, hope, anguish — came pouring in.

In the art of somebody like Caspar David Friedrich or John Martin we see humans dwarfed by the might and sublimity of nature.

Mystery and emotion — despair, love, hope, anguish — came pouring in.

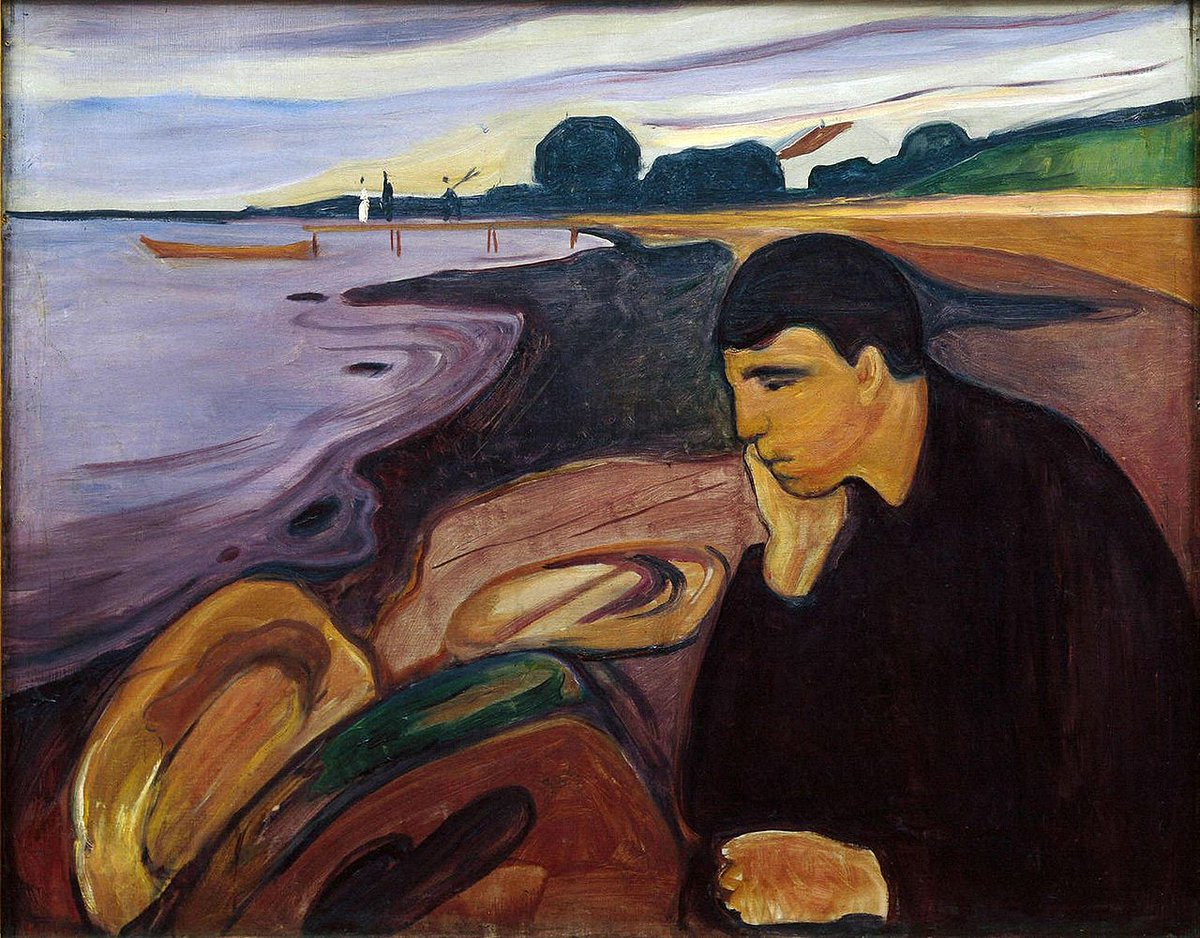

Things changed as the 19th century wore on, as the world started evolving more quickly than ever.

Artists like Vincent van Gogh and Edvard Munch portrayed humans according to their emotions rather than how they "actually" looked.

A retreat inward, from the metamorphosing world?

Artists like Vincent van Gogh and Edvard Munch portrayed humans according to their emotions rather than how they "actually" looked.

A retreat inward, from the metamorphosing world?

Little wonder the rapid technological development and unutterable chaos of the 20th century led to even stranger art.

Cubism, Surrealism, and Abstract Art show a world where we became more self-conscious than ever, where we started to suffer from the curse of too much knowledge.

Cubism, Surrealism, and Abstract Art show a world where we became more self-conscious than ever, where we started to suffer from the curse of too much knowledge.

Though, of course, one contrast with this general 20th century trend was in the art of Communist countries such as the USSR.

More classical ideas thrived there, as spurred on by ideology and state-sponsored art, to present a kind of idealised version of Communist humankind.

More classical ideas thrived there, as spurred on by ideology and state-sponsored art, to present a kind of idealised version of Communist humankind.

And then we arrive at the 21st century, the age of the internet, of social media, and the attention economy.

If the Pyramids represent Egypt, gargoyles the Middle Ages, and David the Renaissance, future historians will surely use one of these images as the emblem of our era.

If the Pyramids represent Egypt, gargoyles the Middle Ages, and David the Renaissance, future historians will surely use one of these images as the emblem of our era.

Just think of how Greek, Medieval, Renaissance, or Impressionist artists might have designed an image that would — literally, given their purpose and prevalence — represent humanity.

A Gothic, Baroque, Expressionist, or Surrealist default profile picture sounds fascinating.

A Gothic, Baroque, Expressionist, or Surrealist default profile picture sounds fascinating.

But our default profile pictures are like everything else we make now: incredibly effective, very convenient, wholly inoffensive... but totally generic, absolutely without character, and (in the end) simply boring.

All forms of design, in any era, always say the same thing.

All forms of design, in any era, always say the same thing.

These pictures show that the fundamental view of a human being, in the 21st century, is of a consumer.

The human is something without identity other than to receive advertising; a blank, generic, interchangeable creature.

Not idealised... just indifferent, and a little creepy.

The human is something without identity other than to receive advertising; a blank, generic, interchangeable creature.

Not idealised... just indifferent, and a little creepy.

After all, the strange thing about these default profile pictures is that, although you've seen each of them thousands of times, they're all interchangeable — you'd struggle to tell which one belongs to which app.

Another sign of our increasingly generic times.

Another sign of our increasingly generic times.

This is surely a phase, and in one hundred years (or less!) things will have changed again.

And there are, of course, great things about life in the 21st century — the mindset that created these profile pictures is what gave us the very comfort and convenience of modern life.

And there are, of course, great things about life in the 21st century — the mindset that created these profile pictures is what gave us the very comfort and convenience of modern life.

Still, the world becomes a better place when it is more interesting.

And though we are instinctively drawn to what is generic, the things we love most are always idiosyncratic.

Those default pictures should be an opportunity to add character to the world, not to standardise it.

And though we are instinctively drawn to what is generic, the things we love most are always idiosyncratic.

Those default pictures should be an opportunity to add character to the world, not to standardise it.

If you liked this you'll probably enjoy my new book, which is a kind of whirlwind introduction to art, architecture, history, and literature.

It's being published by Penguin and it's coming out on 4th September.

You can pre-order it, of course, at the link in my bio.

It's being published by Penguin and it's coming out on 4th September.

You can pre-order it, of course, at the link in my bio.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh