NEW: Is the internet changing our personalities for the worse?

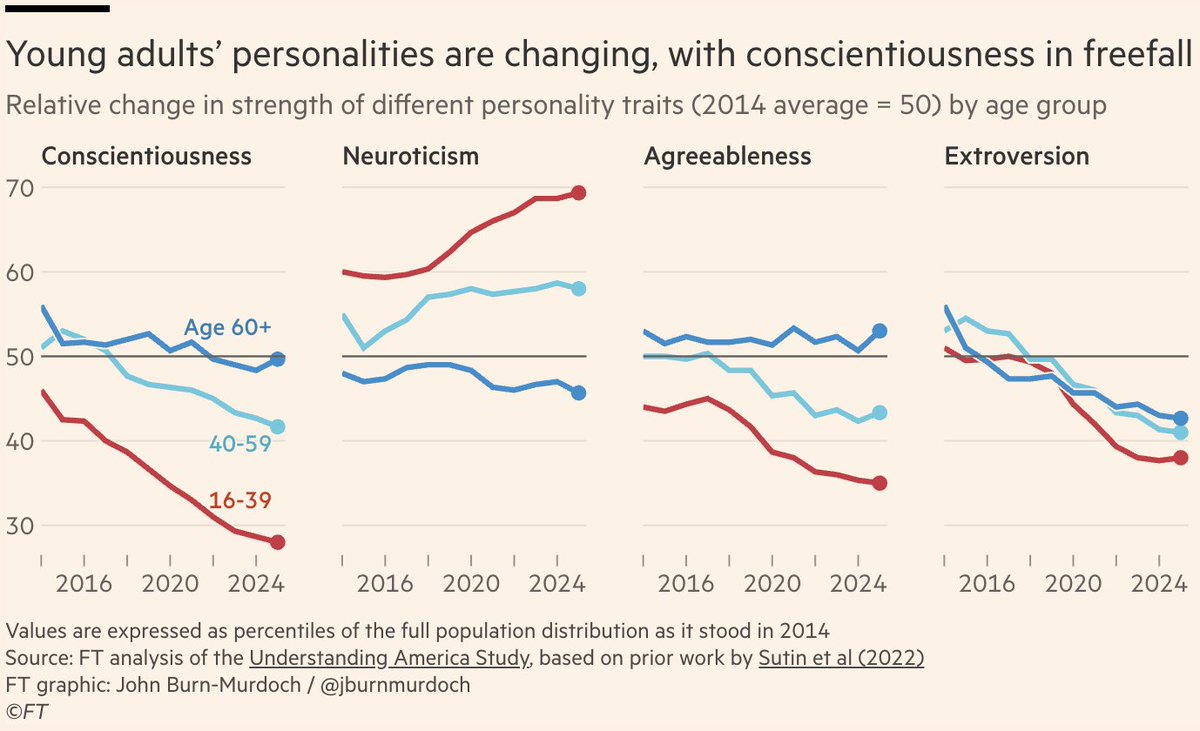

Conscientiousness and extroversion are down, neuroticism up, with young adults leading the charge.

This is a really consequential shift, and there’s a lot going on here, so let’s get into the weeds 🧵

Conscientiousness and extroversion are down, neuroticism up, with young adults leading the charge.

This is a really consequential shift, and there’s a lot going on here, so let’s get into the weeds 🧵

First up, personality analysis can feel vague, and you might well ask why it even matters?

On the first of those, the finding of distinct personality traits is robust. This field of research has been around for decades and holds up pretty well, even across cultures.

On the first of those, the finding of distinct personality traits is robust. This field of research has been around for decades and holds up pretty well, even across cultures.

On the second, studies consistently find personality shapes life outcomes.

In fact, personality traits — esp conscientiousness and neuroticism — are stronger predictors of career success, divorce and mortality than someone’s socio-economic background or cognitive abilities.

In fact, personality traits — esp conscientiousness and neuroticism — are stronger predictors of career success, divorce and mortality than someone’s socio-economic background or cognitive abilities.

Highly conscientious people (dependable, disciplined, committed) fare best of all. They live the longest, succeed at work, their relationships last.

This makes sense. Life isn’t just about knowing what you should do or having the resources to do it, it’s about following through.

This makes sense. Life isn’t just about knowing what you should do or having the resources to do it, it’s about following through.

Conscientiousness is especially critical in the modern world. Life today is full of temptations. From hyper-engaging digital media to online gambling, the ability to ignore it all and put long-term wellbeing ahead of short-term kicks becomes a superpower.

Generative AI could supercharge this dynamic.

A high-C student might use an LLM as a personal tutor to strengthen their knowledge of a concept; their low-C counterpart might task the same LLM with writing their essay, foregoing knowledge acquisition altogether.

A high-C student might use an LLM as a personal tutor to strengthen their knowledge of a concept; their low-C counterpart might task the same LLM with writing their essay, foregoing knowledge acquisition altogether.

So, that’s conscientiousness.

At the other end of the spectrum, people high in neuroticism (anxious, often tense, feel emotions very strongly) tend to face more challenges in life.

Relationships break down, work life is difficult, stress can bring health problems.

At the other end of the spectrum, people high in neuroticism (anxious, often tense, feel emotions very strongly) tend to face more challenges in life.

Relationships break down, work life is difficult, stress can bring health problems.

That’s what makes this chart so important.

People are changing in ways that decades of research suggests will lead to worse life outcomes, and this is particularly true of today’s teens, twenty- and thirty-somethings.

People are changing in ways that decades of research suggests will lead to worse life outcomes, and this is particularly true of today’s teens, twenty- and thirty-somethings.

If the headline terms still feel fuzzy, we can dig into the more detailed traits they’re made up of.

Here are some of the sub-traits inside conscientiousness:

Young people say they increasingly struggle to make plans and follow through on them. They feel distracted, careless.

Here are some of the sub-traits inside conscientiousness:

Young people say they increasingly struggle to make plans and follow through on them. They feel distracted, careless.

They also say they feel less outgoing and talkative (true of everyone, but especially young adults). Young people also report feeling less helpful and less trusting, as well as more argumentative.

Again: these are people’s own self-assessments, not others’ descriptions of them.

Again: these are people’s own self-assessments, not others’ descriptions of them.

These detailed traits lead me to point the finger at the digital world.

Ubiquitous and hyper-engaging digital media has led to an explosion in distraction, as well as making it easier than ever to either not make plans in the first place or to abandon them last minute.

Ubiquitous and hyper-engaging digital media has led to an explosion in distraction, as well as making it easier than ever to either not make plans in the first place or to abandon them last minute.

To put it another way: distractions derail our intentions. And we’re now more distracted than ever.

Distraction is toxic to conscientiousness.

Distraction is toxic to conscientiousness.

As @kylascan has written, the sheer convenience of the online world makes real-life commitments feel messy and effortful

The in-person world encourages conscientiousness. The digital world gives you an opt-out.kyla.substack.com/p/economic-les…

The in-person world encourages conscientiousness. The digital world gives you an opt-out.kyla.substack.com/p/economic-les…

The rise of time spent online and accompanying decline in face-to-face interactions mean less social policing of bad behaviours like “ghosting”. See @_alice_evans here:

If you’re low-C on the internet, you don’t pay the price. Not immediately, at least...ggd.world/p/why-is-onlin…

If you’re low-C on the internet, you don’t pay the price. Not immediately, at least...ggd.world/p/why-is-onlin…

And note the timing of that steep young adult dip in extroversion:

The pandemic years when young people bore the brunt of restrictions on socialising in order to protect others from harm.

Long the most extroverted group in society, young adults are now the most introverted.

The pandemic years when young people bore the brunt of restrictions on socialising in order to protect others from harm.

Long the most extroverted group in society, young adults are now the most introverted.

But I want to end on a more empowering note:

Unlike parental background and genetic make-up, there is a wealth of evidence that personality is malleable — what has been eroded can be rebuilt.

Unlike parental background and genetic make-up, there is a wealth of evidence that personality is malleable — what has been eroded can be rebuilt.

Conscientiousness will separate those who just survive from those who thrive in the 21st century. We can each decide which half of that divide we fall on — but ironically that will take some dedication.

Here’s my article in full: ft.com/content/5cd77e…

Here’s my article in full: ft.com/content/5cd77e…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh