NEW from us: Last year, China started construction on an estimated 95 gigawatts (GW) of new coal power capacity, enough to power the entire UK twice over.

We explain why China's still building new coal power plants, and when and how it might stop and begin phasing out.

We explain why China's still building new coal power plants, and when and how it might stop and begin phasing out.

We address several persistent myths and misconceptions about coal power in China. These are the key points we make:

POINT 1: New coal is not needed for energy security

Making sure there is enough capacity to cover peak demand is what the government (mainly) means when they talk about “energy security” as the justification for new coal power.

Making sure there is enough capacity to cover peak demand is what the government (mainly) means when they talk about “energy security” as the justification for new coal power.

China has more than enough “dispatchable” resources (coal, gas, nuclear, hydropower and biomass) to meet even the highest demand peaks. It also has more than enough underutilised coal-power capacity to meet potential demand growth.

Yet, China saw several regional power shortages in 2020-22. In light of the capacity numbers, the power shortages didn't make any sense at all since the country had and still has dispatchable capacity (coal, gas, nuclear, hydropower dams) far in excess of peak power demand.

So even when the highest demand peak coincides with near-zero generation from solar and wind, there should be no shortage.

The power shortages were caused by inflexible and outdated operation of the power grid. Power plants in neighboring provinces are not utilized to meet demand spikes, even though there is transmission capacity to do so.

The clearest evidence of this is that during the two most dramatic episodes of power shortage, Sichuan in 2022 and Northeast China in 2020, the affected provinces continued to export power to the rest of the country -- when they should have imported or at least stopped exports.

Something needed to be done to keep lights on during summertime demand peaks, but it didn't have to be coal. The government had other options: expediting grid and power market reforms and investing in large scale power storage.

The leadership went for all three: storage investment is happening on a similar scale to coal power, with 200 GW of pumped hydro in the pipeline and 30 GW of battery storage added just last year.

More flexible transmission between provinces has been a key way in which power shortages similar to 2021-22 have largely been avoided in the past two summers despite rapid power demand growth and few of the newly permitted coal power plants being commissioned yet.

POINT 2: Coal power doesn't "lock in" decades of emissions

Market economies are obsessed with efficiency and making sure you don't overbuild, while China's system is concerned with effectiveness and doesn't worry much about overbuilding.

Market economies are obsessed with efficiency and making sure you don't overbuild, while China's system is concerned with effectiveness and doesn't worry much about overbuilding.

So even if it seems two solutions could do the job they'd rather apply three and risk some stranded investment than take any chance of coming up short.

That means that China almost invariably ends up building and eventually closing down excess capacity. Furthermore, the wave of new coal power plants started during zero-Covid when the government was pushing forward all shovel-ready projects to keep the economy humming.

Overbuilding is also less of a concern because the economics of coal plants in China are much closer to gas turbines than coal plants in the west. Building a large 1,000MW coal plant costs ~$500-600mn in China, vs, ~$4bn in the U.S., while fuel costs the same.

POINT 3: Overbuilding coal is not unique to China

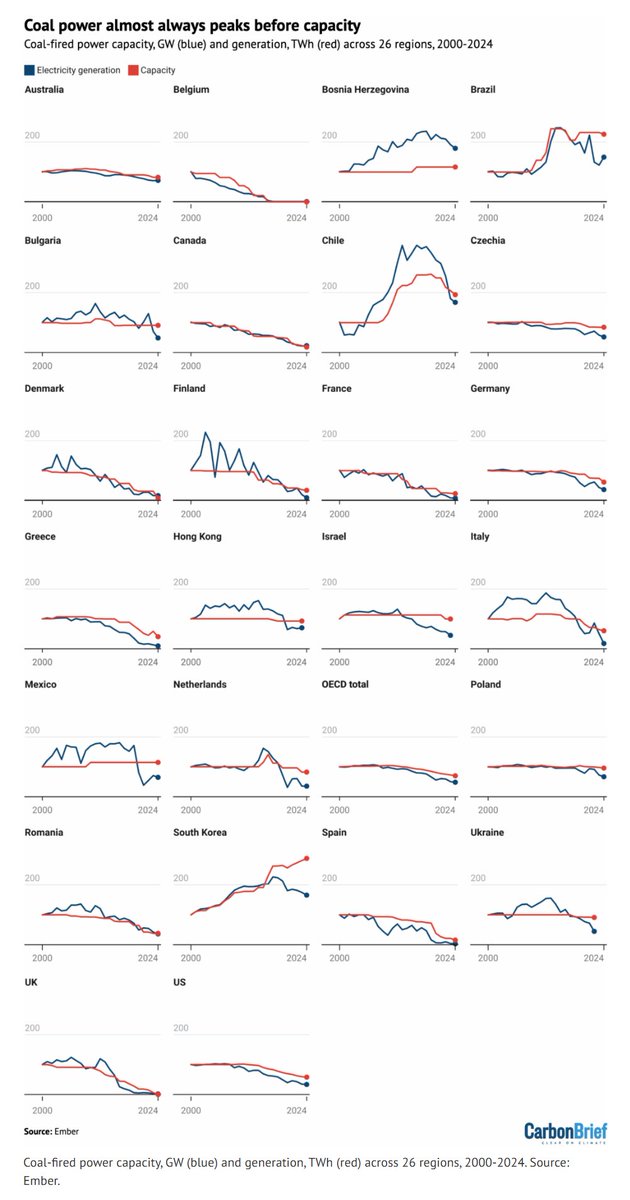

While China is more prone to overcapacity than most other economies, overbuilding coal is not at all unique to China – but rather a rule for countries that have phased down coal.

While China is more prone to overcapacity than most other economies, overbuilding coal is not at all unique to China – but rather a rule for countries that have phased down coal.

We analysed 26 countries that had notable coal power capacity (>2GW) and have peaked coal-fired power generation and reduced it at least 20%. In the clear majority, coal power generation peaked before coal power capacity, and generation has fallen much further from the peak.

So usually it is coal being out-competed in generation that leads to new coal power projects being stopped and existing coal power capacity being closed down, rather than a reduction in capacity leading to generation being cut back.

POINT 4: New coal power plants do not have to mean more coal use or higher emissions.

Building new coal power plants makes emission reductions harder or more expensive in China, so it is a problem, but doesn't make it unavoidable that emissions from power generation will increase as many commentators suggest.

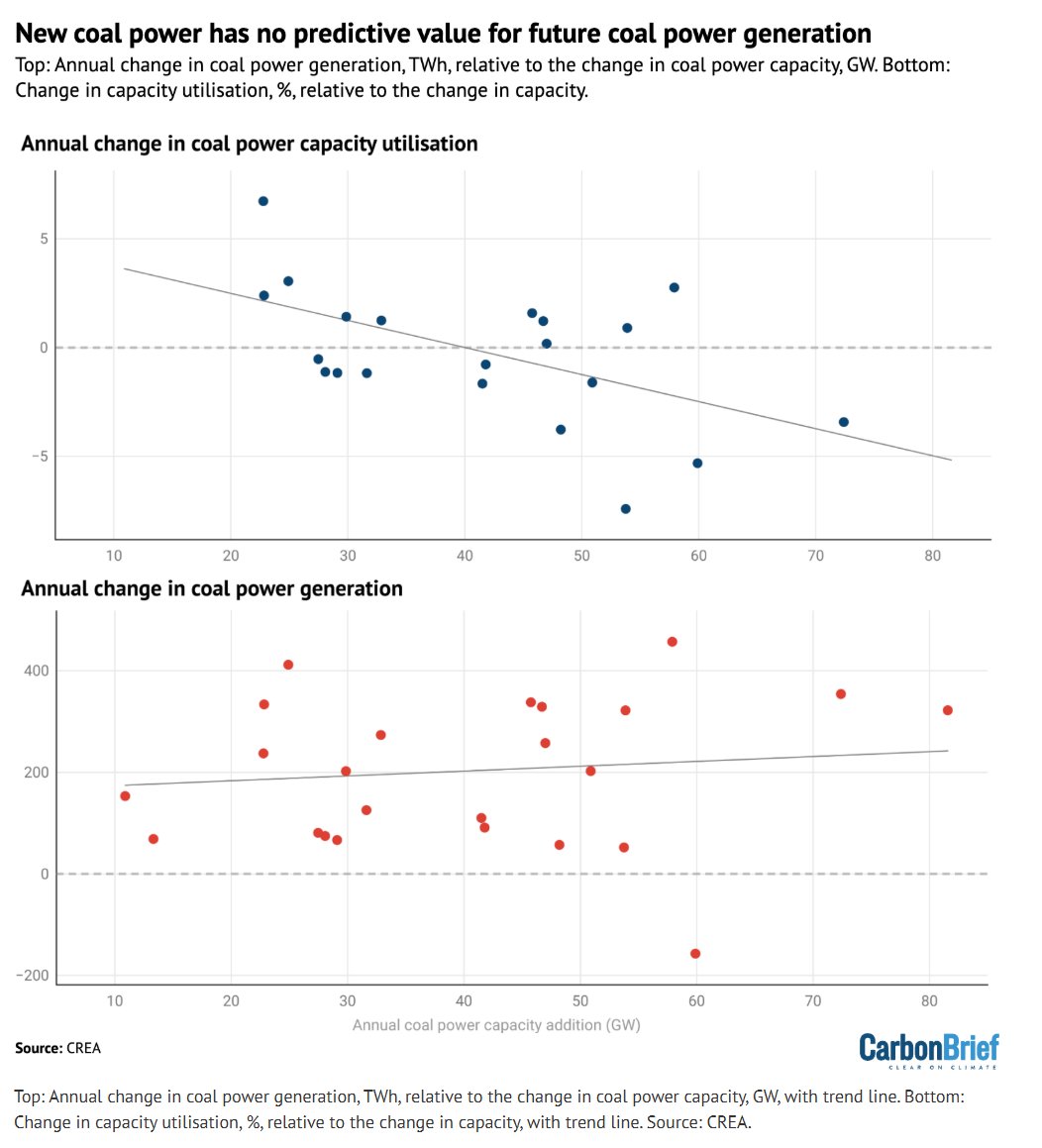

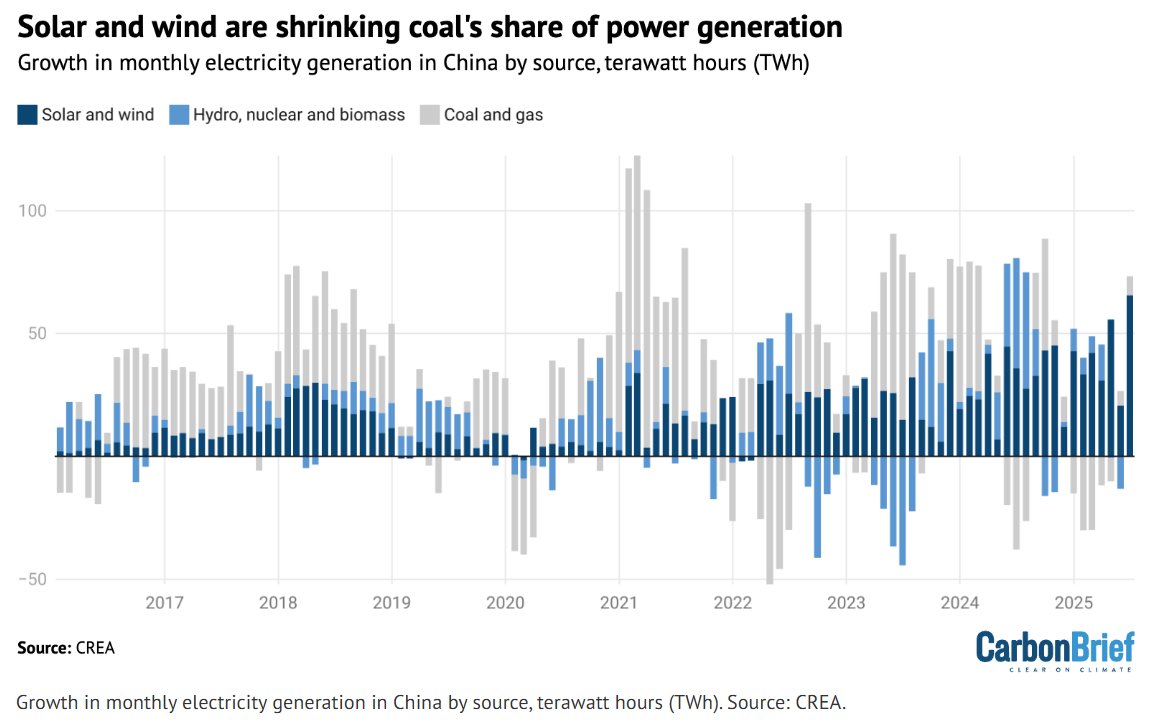

More capacity does not directly lead to more generation. China already has the capacity to generate much more coal power, as the average utilization of plants is about 50%. Generation from coal&gas is determined as a residual of power demand minus generation from clean sources.

It's a basic fact of power markets that coal and gas-fired power plants, which have high fuel costs, only run as much as needed to fill the gap between power demand and supply from low marginal cost sources (solar, wind, hydro, nuclear).

Statistical analysis also shows that new coal power capacity has no value whatsoever in predicting the growth in power generation from coal, or CO2 emissions from power generation in China. Instead, larger capacity additions lead to a drop in coal power utilisation.

The central gov’t wants more coal power capacity, but not necessarily more generation. The catch is that plant operators - big power companies that also run most of the clean energy in China - have an interest to run their brand new coal plants. Provinces have the same interest.

So permitting all these new coal plants has created new conflicts of interest that the central government will need to grapple with to keep the energy transition going. Opposition from coal industry interests meant that grid reforms didn't happen as fast as they should have.

POINT 5: Coal is not yet playing a flexible role or seeing falling utilization.

Since 2022, China’s energy policy has stated that new coal-power projects should serve a “supporting” or “regulating” role, helping integrate variable renewables and respond to demand fluctuations, rather than operating as always-on “baseload” generators.

More broadly, China’s energy strategy also calls for coal power to gradually shift away from a dominant baseload role toward a more flexible, supporting function.

The 2022 policy provided local governments with a new rationale for building coal power, but many of the new plants are still designed and operated as inflexible baseload units.

While low by historical standards and compared to most other countries, the utilization of China's coal power fleet has in fact recovered in recent years due to rapid power demand and earlier restriction of permits.

POINT 6: China will stop new coal projects when the policymakers are confident that the grid and the power system are ready to handle peak loads and power demand growth without the addition of more coal.

With lots of coal power capacity due to come online and clean energy pushing coal-fired power generation down, utilization is likely to fall sharply in the coming years. That's when the hammer should fall and elimination of coal power capacity begin.

What will the beginning of the coal phase-out in China look like once it happens? Likely similar to the overcapacity elimination programs in steel, cement and coal power around 2017, when national targets were set for how much capacity is to be eliminated.

The national capacity elimination targets were then broken down to provinces and central government-owned enterprises, each of which got to choose which units to scupper. The Xi administration rarely leaves things like this to the market to sort out.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh