You're a Soviet railroad commissar. No markets. No prices. Just you and a mountain range between two cities. How do you decide where to build?

This simple question reveals why socialism always fails. 🧵

This simple question reveals why socialism always fails. 🧵

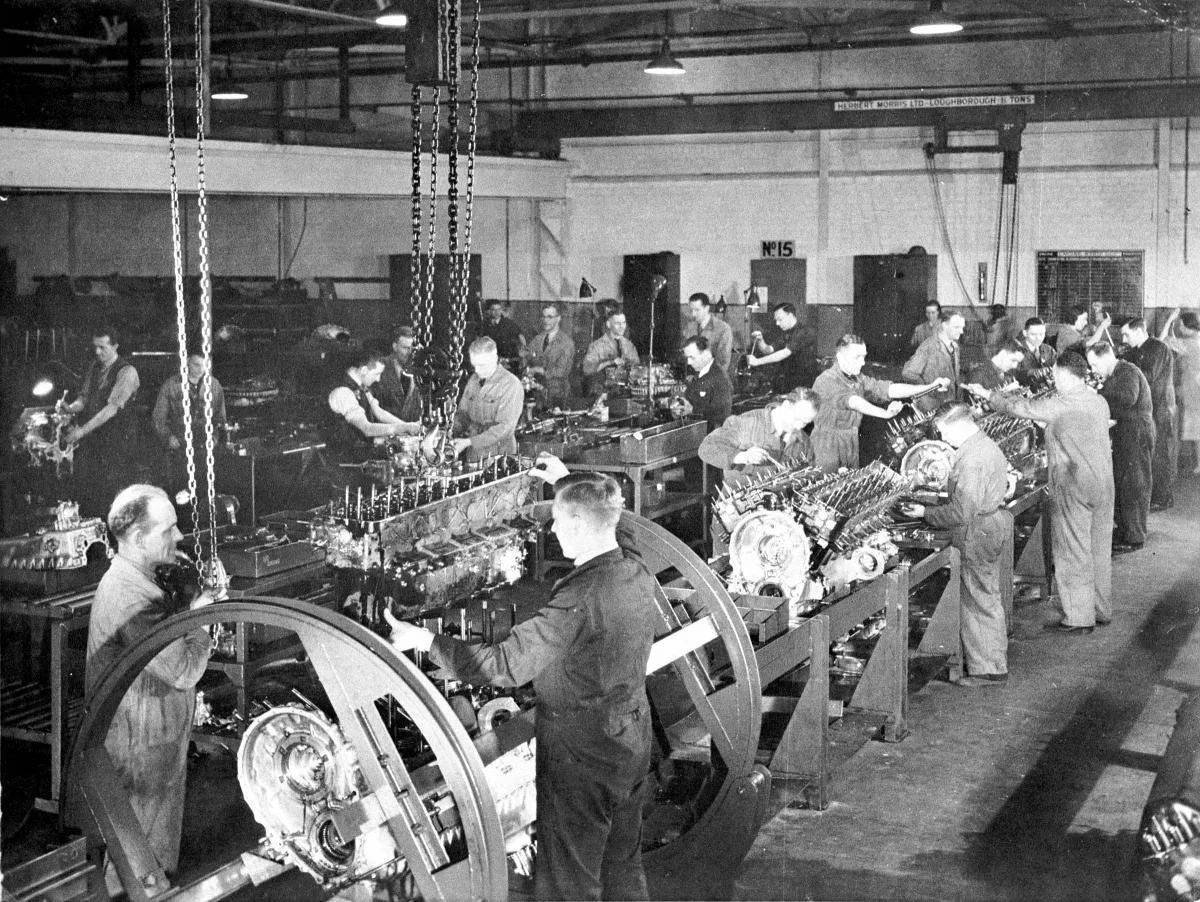

Through the mountains, you'd use less steel but massive engineering resources. Around the mountains, you'd use more steel but save engineering for other projects. Both steel and engineering are desperately needed elsewhere for irrigation, trucks, harbors, thousands of other uses.

To choose wisely, you'd need to know what millions of people know. What farmers know about crop yields. What grocers know about customer demand. What truckers know about delivery capacity. What families know about the meals they want to cook tonight.

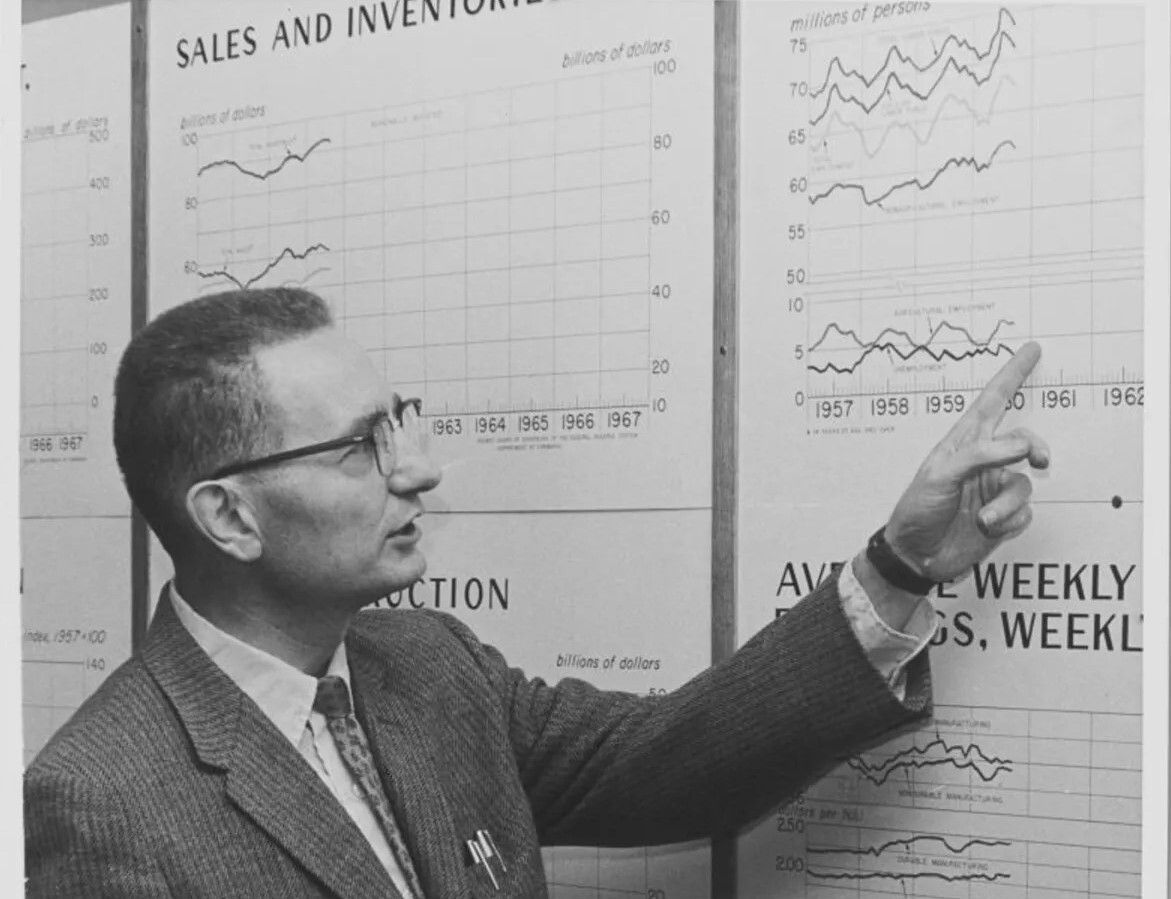

You'd need surveys of millions. By the time you processed the data, it would be obsolete. Even if people could articulate their preferences accurately, which they often can't until facing real choices. Ludwig von Mises called this "groping in the dark."

Now imagine you're not a commissar, but a railroad CEO in a market economy. Your goal isn't "the good of the nation" but profit. You calculate costs: engineering hours × price of engineering + steel tons × price of steel. You choose whatever costs less.

Here's the miracle: By choosing what's cheapest for your company, you automatically choose what's best for society. Those market prices you calculated with? They contain the knowledge and preferences of millions of people you'll never meet.

When customers want better produce, they offer grocers more. Grocers offer farmers more. Farmers offer more for irrigation. Irrigation companies offer engineers more. The price of engineering rises, signaling everyone that this resource just became more valuable.

Prices aren't just numbers. They're a distributed intelligence system that coordinates billions of decisions without anyone being in charge. No commissar needed. No surveys required. Just voluntary exchange revealing truth.

This is why socialism always fails and why markets always win. But most college students never learn this. They graduate thinking prices are arbitrary, that central planning could work "if done right."

What if you could be different? What if you could walk into any economics classroom and actually defend free markets with real arguments?

FINAL WEEK TO CHANGE THAT.

Applications for Students For Liberty's 2025-26 Local Coordinator Program in the US and Canada close August 16th. This is your chance to become the student who actually understands how the world works and can explain it to others.

Ready to stop being the only libertarian on campus?

👉 Apply now: join.studentsforliberty.org

Don't let this opportunity disappear like Soviet bread lines.

What if you could be different? What if you could walk into any economics classroom and actually defend free markets with real arguments?

FINAL WEEK TO CHANGE THAT.

Applications for Students For Liberty's 2025-26 Local Coordinator Program in the US and Canada close August 16th. This is your chance to become the student who actually understands how the world works and can explain it to others.

Ready to stop being the only libertarian on campus?

👉 Apply now: join.studentsforliberty.org

Don't let this opportunity disappear like Soviet bread lines.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh