🧵 ZANU’s Congo Heist — How Generals & Cronies Turned War Into a Billion-Dollar Loot

1/

Aug 1998 — Zimbabwe’s economy is buckling, factories silent, bread queues winding through Harare.

Instead of fixing the crisis, Mugabe dispatches ~11,000 soldiers to prop up Laurent Kabila’s crumbling DRC regime.

The pretext: Pan-African solidarity.

The reality: ZANU-PF hijacking the state — using taxpayers’ money and the national army as a private investment arm for generals, ministers, and businessmen. It was foreign policy as organised crime.

1/

Aug 1998 — Zimbabwe’s economy is buckling, factories silent, bread queues winding through Harare.

Instead of fixing the crisis, Mugabe dispatches ~11,000 soldiers to prop up Laurent Kabila’s crumbling DRC regime.

The pretext: Pan-African solidarity.

The reality: ZANU-PF hijacking the state — using taxpayers’ money and the national army as a private investment arm for generals, ministers, and businessmen. It was foreign policy as organised crime.

2/

In Kinshasa’s war rooms, Zimbabwe’s delegation moved like buyers at an auction.

In essence, it was a cabal — Mnangagwa brokering politics, Zvinavashe guaranteeing military muscle, Shiri running the airlift, Sekeremayi tying up the paperwork.

Orbiting them: Rautenbach (cobalt), Bredenkamp (guns & mining), al-Shanfari (diamonds).

They weren’t defending sovereignty — they were shopping for mineral kingdoms at gunpoint.

In Kinshasa’s war rooms, Zimbabwe’s delegation moved like buyers at an auction.

In essence, it was a cabal — Mnangagwa brokering politics, Zvinavashe guaranteeing military muscle, Shiri running the airlift, Sekeremayi tying up the paperwork.

Orbiting them: Rautenbach (cobalt), Bredenkamp (guns & mining), al-Shanfari (diamonds).

They weren’t defending sovereignty — they were shopping for mineral kingdoms at gunpoint.

3/

They built an extraction machine draped in liberation colours:

OSLEG — ZDF’s corporate mask, grabbing mines and forests.

COSLEG — Congo–Zimbabwe JV that made timber and diamonds a joint family business for two ruling cliques.

Sengamines — a diamond fortress at Mbuji-Mayi, run by soldiers.

Tremalt Ltd — copper/cobalt mines handed over for cents.

The people’s army had been hijacked — its loyalty now pledged to offshore accounts, not the nation.

They built an extraction machine draped in liberation colours:

OSLEG — ZDF’s corporate mask, grabbing mines and forests.

COSLEG — Congo–Zimbabwe JV that made timber and diamonds a joint family business for two ruling cliques.

Sengamines — a diamond fortress at Mbuji-Mayi, run by soldiers.

Tremalt Ltd — copper/cobalt mines handed over for cents.

The people’s army had been hijacked — its loyalty now pledged to offshore accounts, not the nation.

4/

Diamonds — the glittering prize.

Sengamines sat on $1bn+ reserves (UN).

Stones left the country under military escort, bypassing Congo’s treasury and the public good.

Profits fed Harare’s war chest in 2002, a shadow fund for ZANU-PF’s election machine — proof that the DRC mission was as much about holding power in Zimbabwe as it was about plundering a neighbour.

Diamonds — the glittering prize.

Sengamines sat on $1bn+ reserves (UN).

Stones left the country under military escort, bypassing Congo’s treasury and the public good.

Profits fed Harare’s war chest in 2002, a shadow fund for ZANU-PF’s election machine — proof that the DRC mission was as much about holding power in Zimbabwe as it was about plundering a neighbour.

5/

Copper & cobalt — the cash engine.

Tremalt’s 2001 Gécamines deal — brokered in the shadow of ZDF protection — gifted massive mining assets for token sums.

Exports undervalued by $100m+ annually.

This wasn’t commerce; it was daylight robbery with legal paperwork. And every missing dollar was another nail in the coffin of Congo’s recovery.

Copper & cobalt — the cash engine.

Tremalt’s 2001 Gécamines deal — brokered in the shadow of ZDF protection — gifted massive mining assets for token sums.

Exports undervalued by $100m+ annually.

This wasn’t commerce; it was daylight robbery with legal paperwork. And every missing dollar was another nail in the coffin of Congo’s recovery.

6/

Timber & industrial diamonds — the loose change.

COSLEG took logging rights in Équateur and industrial diamonds in Kasai.

ZDF soldiers became rent-a-guards for private mills and sorting houses — men paid by Zimbabwe’s taxpayers, deployed as the personal security arm of Harare’s business cronies.

Timber & industrial diamonds — the loose change.

COSLEG took logging rights in Équateur and industrial diamonds in Kasai.

ZDF soldiers became rent-a-guards for private mills and sorting houses — men paid by Zimbabwe’s taxpayers, deployed as the personal security arm of Harare’s business cronies.

7/

This wasn’t a war economy by accident — it was the business plan.

The DRC mission burned $1m/day from Zimbabwe’s treasury.

The mineral profits never saw a budget line — they went straight into the pockets of ministers, generals, and businessmen. It was kleptocracy so naked it didn’t even bother to hide behind ideology anymore.

This wasn’t a war economy by accident — it was the business plan.

The DRC mission burned $1m/day from Zimbabwe’s treasury.

The mineral profits never saw a budget line — they went straight into the pockets of ministers, generals, and businessmen. It was kleptocracy so naked it didn’t even bother to hide behind ideology anymore.

8/

Congo cash kept ZANU-PF’s power machine running at full throttle.

It bought farms for loyalists, mansions for military chiefs, and fleets of luxury cars for businessmen who could whisper in the president’s ear.

As Zimbabweans queued for bread, the ruling class drank champagne bought with Congolese diamonds and cobalt — the clearest proof that suffering is a political choice when greed is in charge.

Congo cash kept ZANU-PF’s power machine running at full throttle.

It bought farms for loyalists, mansions for military chiefs, and fleets of luxury cars for businessmen who could whisper in the president’s ear.

As Zimbabweans queued for bread, the ruling class drank champagne bought with Congolese diamonds and cobalt — the clearest proof that suffering is a political choice when greed is in charge.

9/

The human cost in Congo:

3.5–5 million dead (1998–2002).

Civilians raped, enslaved, extorted, and beaten in mining zones.

Soldiers unpaid, hospitals without drugs, schools shuttered.

Several armies — DRC, Zimbabwe, Rwanda, Uganda — turned Congo into a graveyard and a quarry, stripping its minerals while its people bled.

The human cost in Congo:

3.5–5 million dead (1998–2002).

Civilians raped, enslaved, extorted, and beaten in mining zones.

Soldiers unpaid, hospitals without drugs, schools shuttered.

Several armies — DRC, Zimbabwe, Rwanda, Uganda — turned Congo into a graveyard and a quarry, stripping its minerals while its people bled.

10/

By late 2002, after the UN named names — including Air Marshal Perence Shiri, Defence Minister Moven Mahachi, and Congolese Mining Minister Mwenze Kongolo — Zimbabwe began pulling troops out of Congo.

But the retreat was theatre — the real assets were never the soldiers, but the contracts, concessions, and bank accounts.

Mining rights were quietly folded into offshore companies. Key ventures like COSLEG and Sengamines were restructured under new fronts.

The uniforms went home; the money pipeline stayed wide open.

By late 2002, after the UN named names — including Air Marshal Perence Shiri, Defence Minister Moven Mahachi, and Congolese Mining Minister Mwenze Kongolo — Zimbabwe began pulling troops out of Congo.

But the retreat was theatre — the real assets were never the soldiers, but the contracts, concessions, and bank accounts.

Mining rights were quietly folded into offshore companies. Key ventures like COSLEG and Sengamines were restructured under new fronts.

The uniforms went home; the money pipeline stayed wide open.

11/

They called it solidarity.

In reality, it was the largest foreign resource grab in Zimbabwe’s history — and a masterclass in how to turn the tools of statehood into a syndicate for personal enrichment.

The graves stayed in Congo.

The money stayed offshore.

And the lesson to ZANU’s elite was clear: a soldier’s rifle is not just for war — it’s for business.

They called it solidarity.

In reality, it was the largest foreign resource grab in Zimbabwe’s history — and a masterclass in how to turn the tools of statehood into a syndicate for personal enrichment.

The graves stayed in Congo.

The money stayed offshore.

And the lesson to ZANU’s elite was clear: a soldier’s rifle is not just for war — it’s for business.

12/

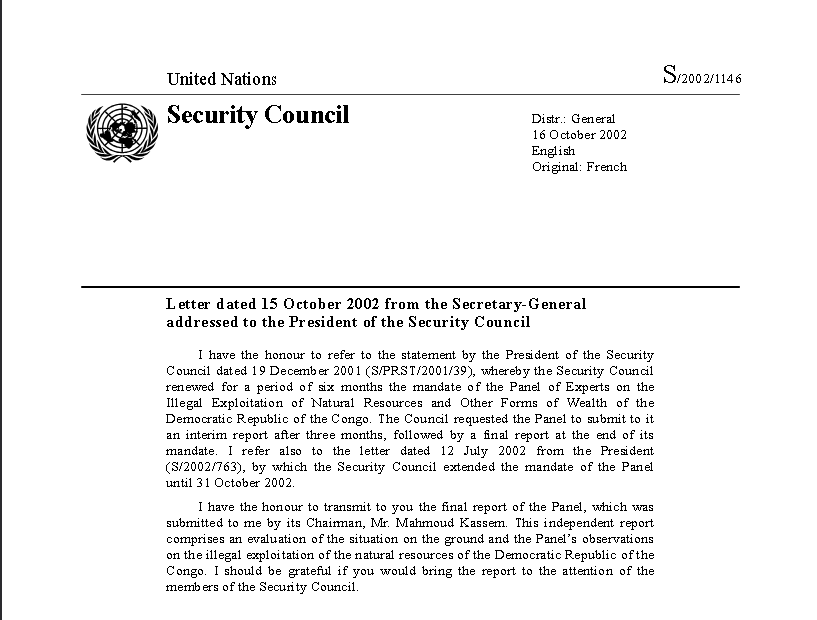

Sources:

UN Panel of Experts on the Illegal Exploitation of Natural Resources (S/2002/1146)

Zimbabwe Independent (2000–2003)

2002 Election Zimbabwe report

HRW, The War Within the War (2002)

Sources:

UN Panel of Experts on the Illegal Exploitation of Natural Resources (S/2002/1146)

Zimbabwe Independent (2000–2003)

2002 Election Zimbabwe report

HRW, The War Within the War (2002)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh