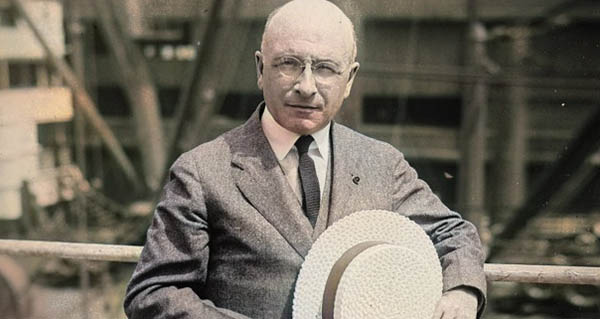

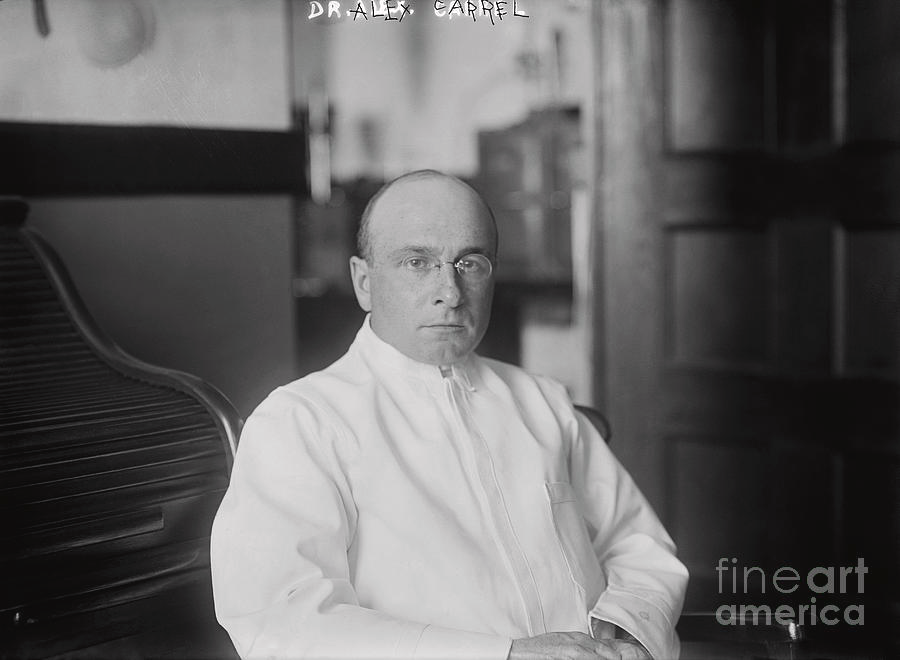

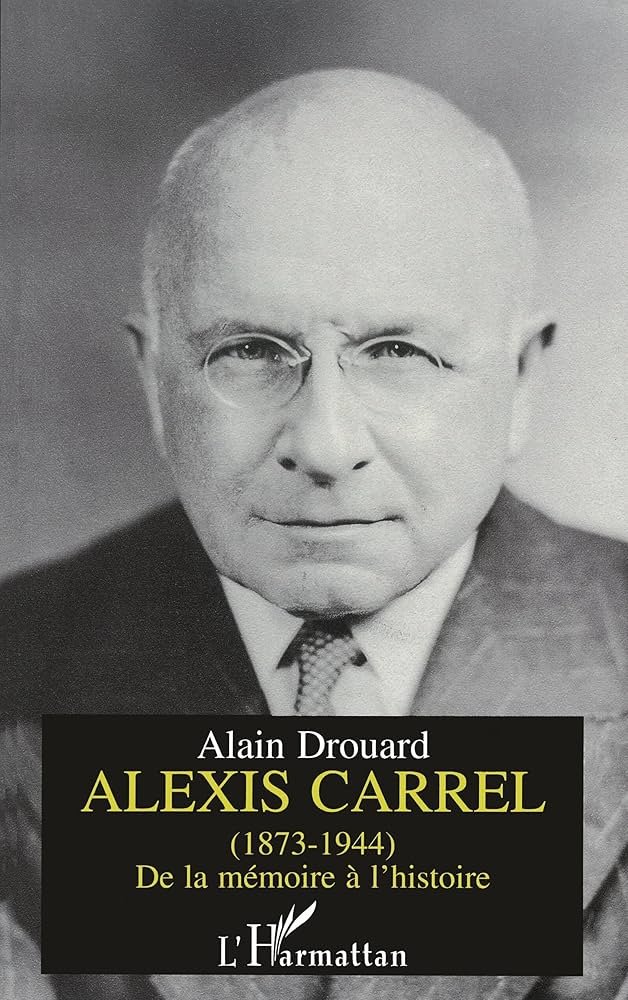

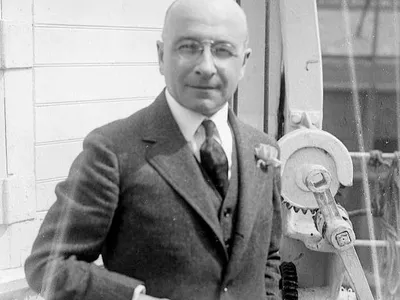

In 1912, Alexis Carrel won the Nobel Prize in Medicine.

He was a brilliant doctor, and an outspoken skeptic.

No miracles, no supernatural. He didn't believe in God, let alone the Catholic Church.

Until one trip to Lourdes changed everything.

The scientist who converted - a 🧵

He was a brilliant doctor, and an outspoken skeptic.

No miracles, no supernatural. He didn't believe in God, let alone the Catholic Church.

Until one trip to Lourdes changed everything.

The scientist who converted - a 🧵

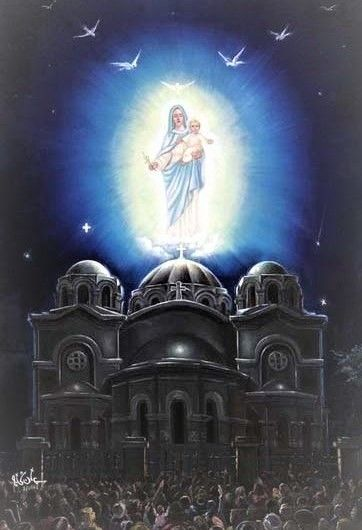

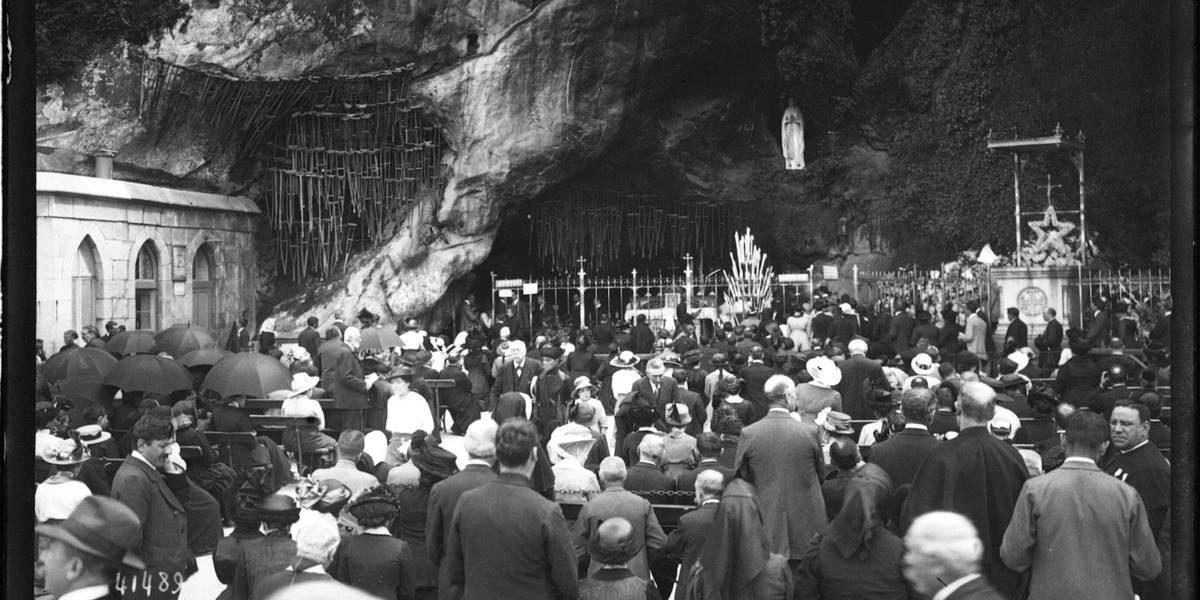

From the time of Blessed Mary’s first apparition to Bernadette Soubirous, the water from the Lourdes Grotto has been a source of miraculous healing both for those who have visited the Grotto and even for those who used the water in remote places.

Since the time of Bernadette, over 7,000 miraculous cures have been reported to the Lourdes Medical Bureau by pilgrims who have visited Lourdes (this does not include miracles that have taken place outside of Lourdes).

There were so many purported cures associated with the water and Grotto of Lourdes that the Catholic Church set up the Lourdes Medical Bureau to be constituted by and under the leadership of physicians and scientists alone.

Since the time of Bernadette, over 7,000 miraculous cures have been reported to the Lourdes Medical Bureau by pilgrims who have visited Lourdes (this does not include miracles that have taken place outside of Lourdes).

There were so many purported cures associated with the water and Grotto of Lourdes that the Catholic Church set up the Lourdes Medical Bureau to be constituted by and under the leadership of physicians and scientists alone.

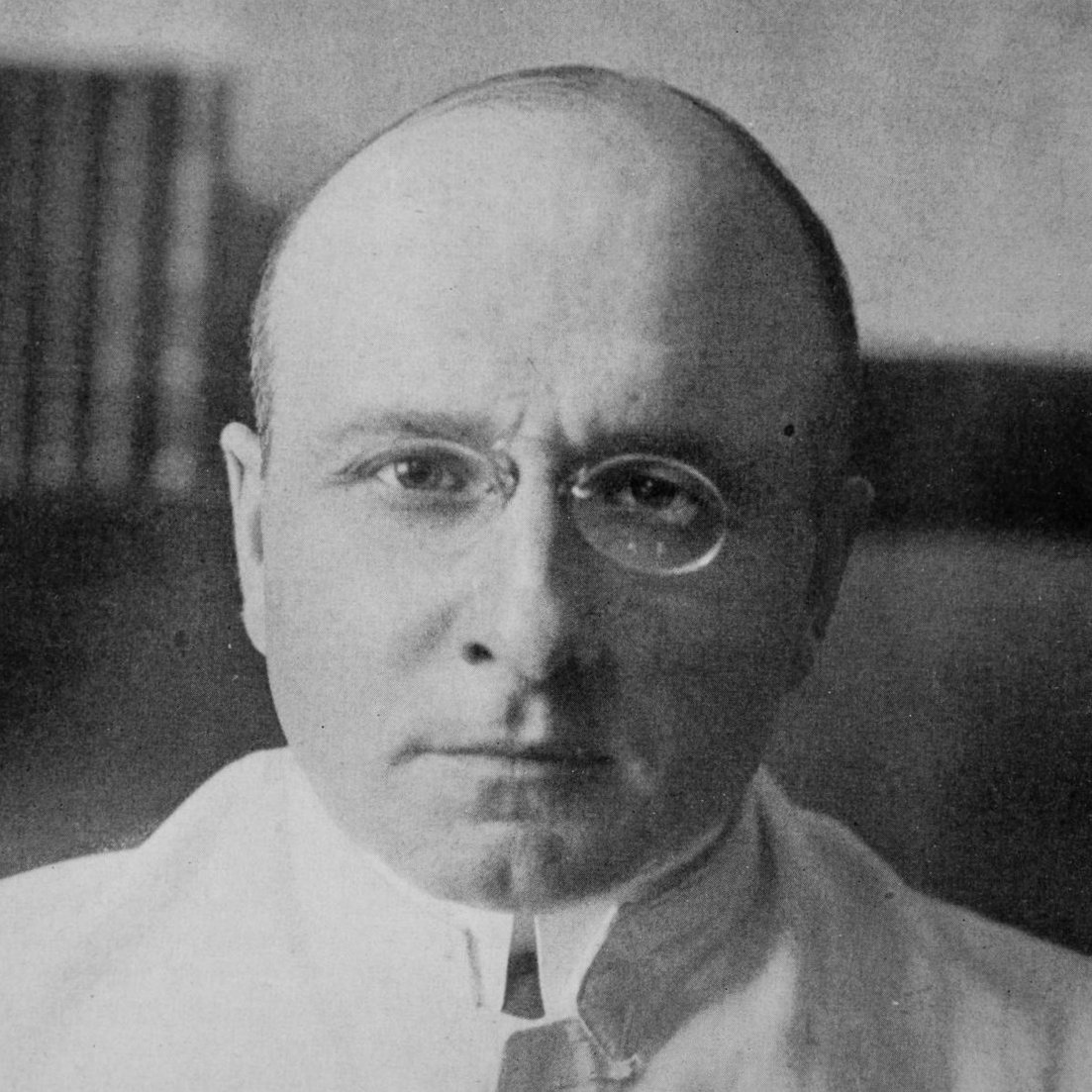

In 1902, a physician friend of Dr. Carrel invited him to help take care of sick patients transported on a train from Lyons to Lourdes.

Though Carrel was born Catholic, he was at that time an agnostic who did not believe in miracles.

Nevertheless, he consented to help out, both because of friendship and an interest in what natural causes might be allowing such fast healings as those claimed at Lourdes.

Though Carrel was born Catholic, he was at that time an agnostic who did not believe in miracles.

Nevertheless, he consented to help out, both because of friendship and an interest in what natural causes might be allowing such fast healings as those claimed at Lourdes.

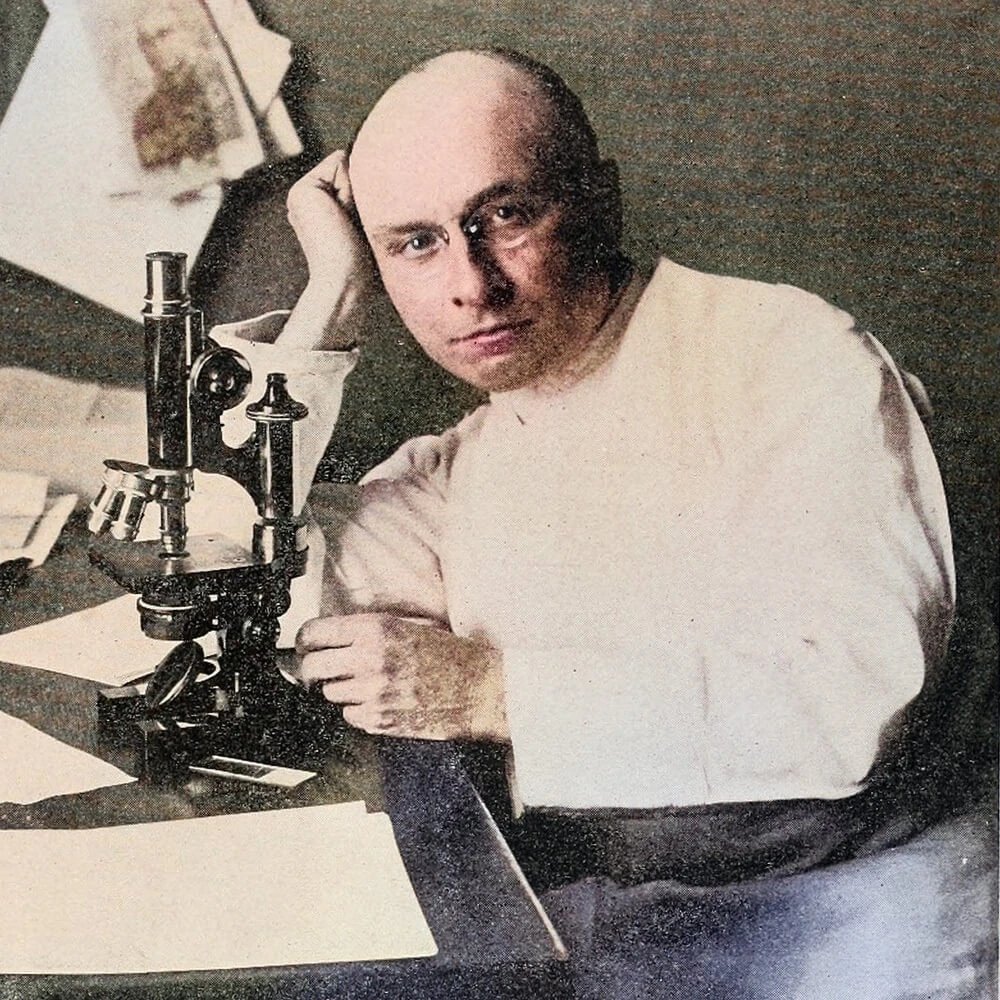

Carrel didn’t go to Lourdes as a pilgrim, but as a clinical observer.

He was determined to study the healings… and expose any fraud.

He was determined to study the healings… and expose any fraud.

On May 28, 1902, Carrel met Marie Bailly.

She was terminally ill. She was suffering from acute tuberculous peritonitis and considerable abdominal distension with large hard masses.

Her abdomen was swollen, her pain unbearable, breathing labored.

Though Marie Bailly was half-conscious, Carrel believed she would pass away quite quickly after arriving at Lourdes, if not before.

Other physicians on the train agreed with this diagnosis.

She was terminally ill. She was suffering from acute tuberculous peritonitis and considerable abdominal distension with large hard masses.

Her abdomen was swollen, her pain unbearable, breathing labored.

Though Marie Bailly was half-conscious, Carrel believed she would pass away quite quickly after arriving at Lourdes, if not before.

Other physicians on the train agreed with this diagnosis.

Carrel boarded the pilgrim train to Lourdes with her.

Not out of faith, but to “see for himself.”

Science, he thought, would explain everything.

When the train arrived at Lourdes, Marie was taken to the Grotto, where three water pitchers poured over her distended abdomen.

What happened next, Carrel would never forget.

Not out of faith, but to “see for himself.”

Science, he thought, would explain everything.

When the train arrived at Lourdes, Marie was taken to the Grotto, where three water pitchers poured over her distended abdomen.

What happened next, Carrel would never forget.

After the first pour, she felt a searing pain. After the second pour, it was lessened. Finally, after the third pour, she experienced a pleasant sensation.

Her stomach began to flatten, and her pulse returned to normal. Carrel was standing behind Marie (along with other physicians), taking notes as the water was poured over her abdomen. He wrote:

“The enormously distended and very hard abdomen began to flatten and within 30 minutes it had completely disappeared. No discharge whatsoever was observed from the body.”

Her stomach began to flatten, and her pulse returned to normal. Carrel was standing behind Marie (along with other physicians), taking notes as the water was poured over her abdomen. He wrote:

“The enormously distended and very hard abdomen began to flatten and within 30 minutes it had completely disappeared. No discharge whatsoever was observed from the body.”

Marie then sat up in bed, had dinner (without vomiting), got out of bed on her own, and dressed herself the next day. She then boarded the train, rode on the hard benches, and arrived in Lyons refreshed. Carrel was still interested in her psychological and physical condition, so he asked that she be monitored by a psychiatrist and a physician for four months.

After her healing, Marie joined the Sisters of Charity, to work with the sick and the poor in a very strenuous life, and died in 1937 at the age of 58.

After her healing, Marie joined the Sisters of Charity, to work with the sick and the poor in a very strenuous life, and died in 1937 at the age of 58.

When Carrel witnessed this exceedingly rapid and medically inexplicable event, he believed he had seen something like a miracle.

However, it was difficult for him to part with his former skeptical agnosticism, so he did not yet return to the Catholic faith of his childhood.

Furthermore, he wanted to avoid being a medical witness to a miraculous event because he knew that, if it became public, it would ruin his career at the medical faculty at Lyons.

Nevertheless, Marie Bailly’s cure seemed so evidently miraculous (being so rapid, complete, and inexplicable) that it became public in the news media in France and worldwide.

Reporters indicated that Carrel did not think the cure was a miracle, which forced Carrel to write a public reply stating that one side (that of some believers) was jumping to a miraculous conclusion too rapidly.

The other side (the medical community) had unjustifiably refused to look at facts that appeared to be miraculous. Indeed, Carrel implied that Bailly’s cure may have been miraculous.

However, it was difficult for him to part with his former skeptical agnosticism, so he did not yet return to the Catholic faith of his childhood.

Furthermore, he wanted to avoid being a medical witness to a miraculous event because he knew that, if it became public, it would ruin his career at the medical faculty at Lyons.

Nevertheless, Marie Bailly’s cure seemed so evidently miraculous (being so rapid, complete, and inexplicable) that it became public in the news media in France and worldwide.

Reporters indicated that Carrel did not think the cure was a miracle, which forced Carrel to write a public reply stating that one side (that of some believers) was jumping to a miraculous conclusion too rapidly.

The other side (the medical community) had unjustifiably refused to look at facts that appeared to be miraculous. Indeed, Carrel implied that Bailly’s cure may have been miraculous.

As Carrel feared, his advocacy of the possibility of Bailly’s miraculous cure led to the end of his career at the medical faculty of Lyons, which ironically had a very good effect on his future; it led him to the University of Chicago and then to the Rockefeller University. In 1912, he received the Nobel Prize for his work in vascular anastomosis.

Carrel returned to Lourdes many times and, on one occasion, witnessed a second miracle: the instantaneous cure of an 18-month-old blind boy.

Carrel returned to Lourdes many times and, on one occasion, witnessed a second miracle: the instantaneous cure of an 18-month-old blind boy.

Despite these two miracles, Carrel could not bring himself to conclusively affirm the reality of miracles, the real divine supernatural intervention manifest in the world.

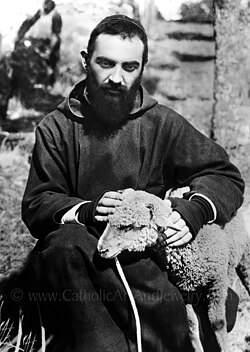

Then, in 1938, one year after the death of Sr. Marie Bailly, Carrel became friends with the Rector of the Major Seminary in Rennes, who told him to consult with a Trappist monk (who was a well-known spiritual director and friend of Charles de Gaulle), Fr. Alexis Presse.

Then, in 1938, one year after the death of Sr. Marie Bailly, Carrel became friends with the Rector of the Major Seminary in Rennes, who told him to consult with a Trappist monk (who was a well-known spiritual director and friend of Charles de Gaulle), Fr. Alexis Presse.

Soon, Fr. Presse and Carrel began a dialogue. In 1942, Carrel announced that he believed in God, the immortality of the soul, and the teachings of the Catholic Church.

Two years later, in 1944, as Carrel was dying in Paris, he sent for Fr. Presse, who administered the Last Rites of the Church to him. He had not been able to let go of the miracles of Lourdes, and they had led him to continue his inquiry into his spiritual nature and Christian revelation. Ultimately, he would find himself joined to the Lord through the Church of his childhood.

Two years later, in 1944, as Carrel was dying in Paris, he sent for Fr. Presse, who administered the Last Rites of the Church to him. He had not been able to let go of the miracles of Lourdes, and they had led him to continue his inquiry into his spiritual nature and Christian revelation. Ultimately, he would find himself joined to the Lord through the Church of his childhood.

Alexis Carrel proved that a true scientist does not fear the truth.

Lourdes stands as a reminder that God is not bound by the limits of human reason.

For Alexis Carrel, two undeniable miracle tore down a lifetime of doubt, and opened the way to eternity.

Deo Gratias!

Lourdes stands as a reminder that God is not bound by the limits of human reason.

For Alexis Carrel, two undeniable miracle tore down a lifetime of doubt, and opened the way to eternity.

Deo Gratias!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh