These aren't castles, palaces, or cathedrals.

They're all water towers, literally just bits of infrastructure relating to water management.

Is it worth the additional cost and resources to make things look like this... or is it a waste?

They're all water towers, literally just bits of infrastructure relating to water management.

Is it worth the additional cost and resources to make things look like this... or is it a waste?

These old water towers are an architectural subgenre of their own.

There are hundreds, mostly Neo-Gothic, and all add something wonderful to the skylines of their cities.

Like the one below in Bydgoszcz, Poland, from 1900.

But, most importantly, they're just infrastructure.

There are hundreds, mostly Neo-Gothic, and all add something wonderful to the skylines of their cities.

Like the one below in Bydgoszcz, Poland, from 1900.

But, most importantly, they're just infrastructure.

We don't think of infrastructure as something that can improve how a town looks and feels.

Infrastructure is necessary to make life convenient; but also, we believe, definitionally boring.

These water towers prove that doesn't have to, and shouldn't be, the case.

Infrastructure is necessary to make life convenient; but also, we believe, definitionally boring.

These water towers prove that doesn't have to, and shouldn't be, the case.

Most amazing is that these towers — remember, just bits of water management infrastructure! — have actually made their respective towns or cities more interesting, not less.

It would have been cheaper and easier to make them simpler, like this more typical example:

It would have been cheaper and easier to make them simpler, like this more typical example:

But their longevity, and the fact they have survived, is testament to the fact that aesthetic appeal isn't some sort of "bonus" when designing buildings or infrastructure.

To make something look nice is a thoroughly sensible investment of resources, time, and effort.

To make something look nice is a thoroughly sensible investment of resources, time, and effort.

There are a few reasons for that.

First: the nicer things look — meaning, simply, the more people like them — the longer they are likely to last.

It's surely wiser to build something that will survive for centuries instead of being demolished and rebuilt in a few decades.

First: the nicer things look — meaning, simply, the more people like them — the longer they are likely to last.

It's surely wiser to build something that will survive for centuries instead of being demolished and rebuilt in a few decades.

Because, rather than being demolished when they became obsolete, the architecture of these water towers has turned them into landmarks worth preserving and adapting.

Whether like the Lüneburg Water Tower, which is now (along with being a gallery) a viewing platform:

Whether like the Lüneburg Water Tower, which is now (along with being a gallery) a viewing platform:

Or the Prenzlauer Berg Water Tower in Berlin, which (along with having a gallery space also) serves as an apartment block:

Or the quite remarkable Schoonhoven Water Tower, perhaps the most refined and sophisticated of all.

This was converted into a workshop and gallery for silversmiths after it was decommissioned.

This was converted into a workshop and gallery for silversmiths after it was decommissioned.

Or even something like the Mannheim Water Tower, which hasn't been adapted to a new purpose yet and simply serves as a landmark.

The Mannheim Tower was so beloved that it was rebuilt to its original appearance after being damaged during WWII.

Infrastructure can even be iconic.

The Mannheim Tower was so beloved that it was rebuilt to its original appearance after being damaged during WWII.

Infrastructure can even be iconic.

Second: there's also the accumulative benefit of beautiful buildings, and how they combine to create charming cities or towns that people want to live in and tourists want to visit.

Buildings or infrastructure are never isolated; they are always part of a broader picture.

Buildings or infrastructure are never isolated; they are always part of a broader picture.

If you removed all of Venice's lovely Medieval and Renaissance architecture... the tourism would dry up!

The same for Paris.

No doubt people would still visit for its museums and culture, but Paris' appearance is a vital and inseparable part of what makes it so appealing.

The same for Paris.

No doubt people would still visit for its museums and culture, but Paris' appearance is a vital and inseparable part of what makes it so appealing.

To invest in beautiful architecture (or, more importantly and simply, characteristic architecture) is to invest in the future of a given city or town or region.

King Ludwig of Bavaria's eccentric, expensive Neuschwanstein Castle has more than paid back its cost to Bavaria.

King Ludwig of Bavaria's eccentric, expensive Neuschwanstein Castle has more than paid back its cost to Bavaria.

The same is true for the Sagrada Família, and for the architecture of Barcelona more generally.

Gaudí's buildings cost time and effort and resources... but they have all been worthwhile investments that helped turn Barcelona into one of the world's most beloved cities.

Gaudí's buildings cost time and effort and resources... but they have all been worthwhile investments that helped turn Barcelona into one of the world's most beloved cities.

Third: making cities and towns prettier for the people who live in them has knock-on consequences.

Human happiness itself seems like a worthy investment, after all.

And, even keeping a purely economic perspective, people who are happier are also more productive.

Human happiness itself seems like a worthy investment, after all.

And, even keeping a purely economic perspective, people who are happier are also more productive.

So this isn't about past versus present, about so-called "traditional architecture" versus so-called "modern architecture."

I, for one, happened to love Brutalism, and Brutalist water towers (like this one in Finland) are no exception.

Alas, the majority doesn't feel that way!

I, for one, happened to love Brutalism, and Brutalist water towers (like this one in Finland) are no exception.

Alas, the majority doesn't feel that way!

People sometimes criticise posts like this by saying that old and beautiful buildings are just examples of survivorship bias.

Yes... that's the point!

It doesn't matter whether the past was more or less beautiful; what matters is how we can improve the present.

Yes... that's the point!

It doesn't matter whether the past was more or less beautiful; what matters is how we can improve the present.

If these water towers are, indeed, examples of survivorship bias (in the sense that the past's uglier buildings have been demolished) then this is simply proof of the fact we should build more things like them, because their survival is evidence of what the public love most.

Anyway, the crucial fact is that these towers didn't end up looking how they do by accident.

It was a conscious choice to design them in a way that the public would enjoy and that would enhance the cities where they happened to be built.

And that choice is still open to us.

It was a conscious choice to design them in a way that the public would enjoy and that would enhance the cities where they happened to be built.

And that choice is still open to us.

Every year we build hundreds of thousands of new bits of infrastructure: sewage plants, roads, bridges, signs, power stations, junction boxes, telegraph poles, and so much more.

Not all of it needs to or should be designed like those old water towers, of course.

Not all of it needs to or should be designed like those old water towers, of course.

But, as those water towers prove, it would surely be a good investment of resources, time, and effort to build certain bits of infrastructure with more care and thought, with a bigger timespan in mind, and with more attention to local heritage and what the public prefers.

Every single time we build something new, whether a bench or skyscraper, there's a straightforward choice: do we want this new thing to improve the appearance and character of its location, or detract from it?

Those old water towers represent the first option.

Those old water towers represent the first option.

Anyway, there's a separate but related discussion about whether buildings' appearances should reflect their purpose, and whether these water towers are "fake" because of how they look.

But that's for another time; and, in any case, it's not something that bothers most people.

But that's for another time; and, in any case, it's not something that bothers most people.

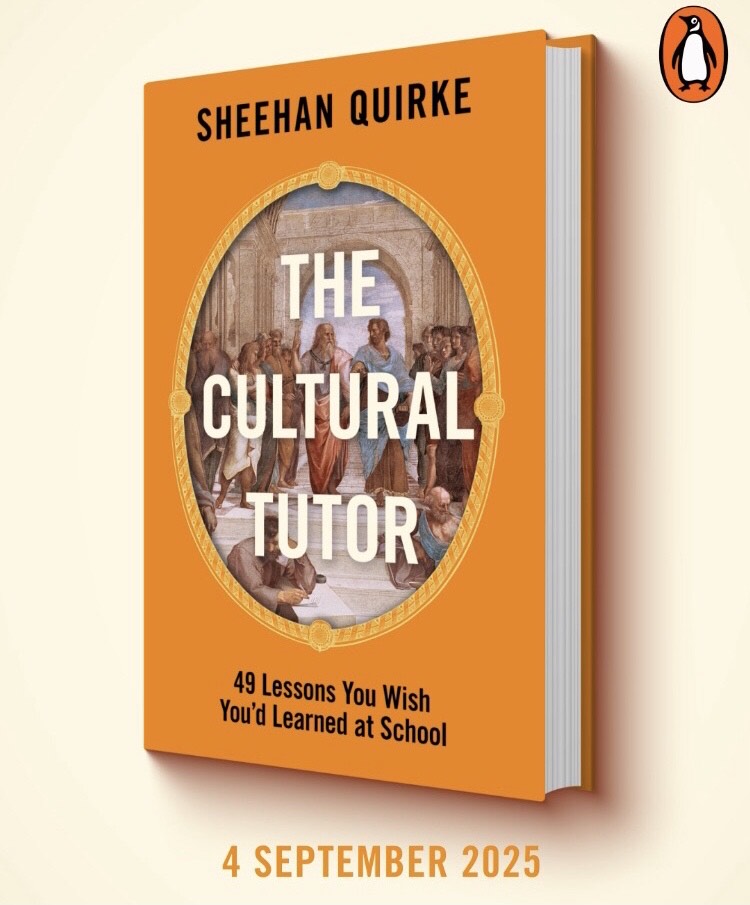

If you liked this then you'll enjoy my new book, coming out 4th September.

It's an introduction to culture — art, architecture, history, literature — as an alternative to doomscrolling and the 24 hour content cycle.

You can pre-order it, of course, at the link in my bio.

It's an introduction to culture — art, architecture, history, literature — as an alternative to doomscrolling and the 24 hour content cycle.

You can pre-order it, of course, at the link in my bio.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh