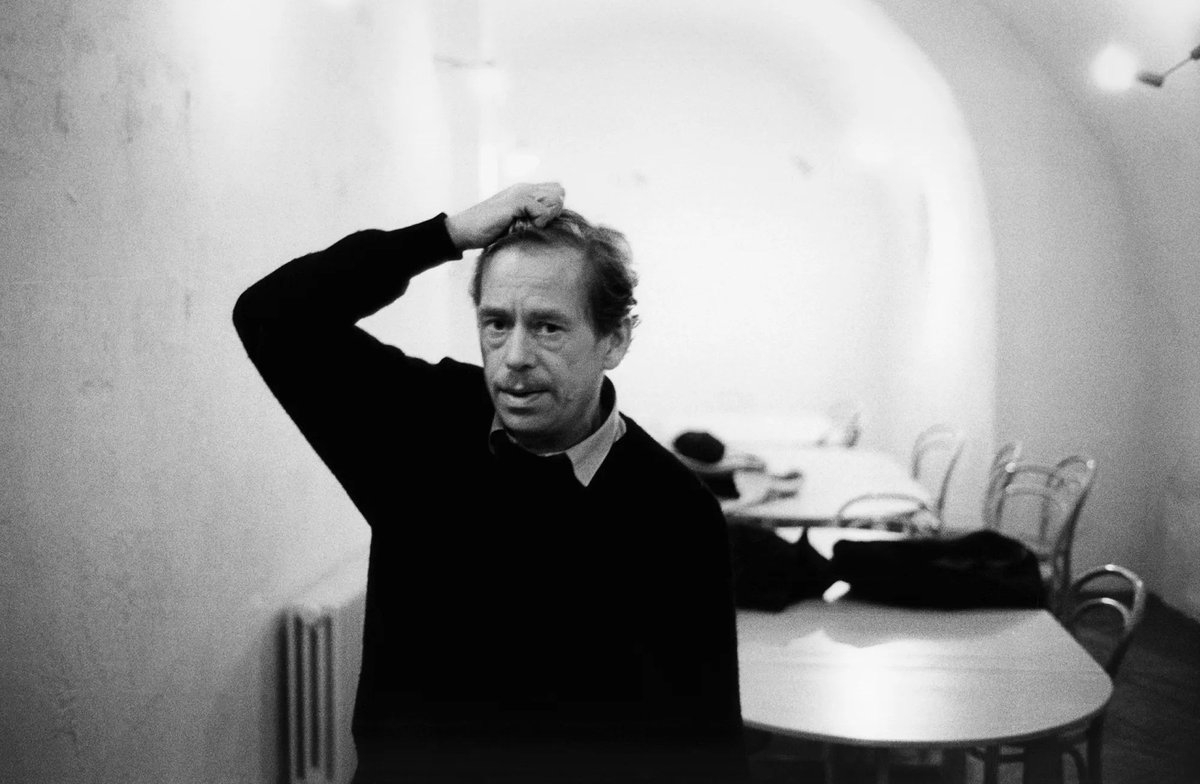

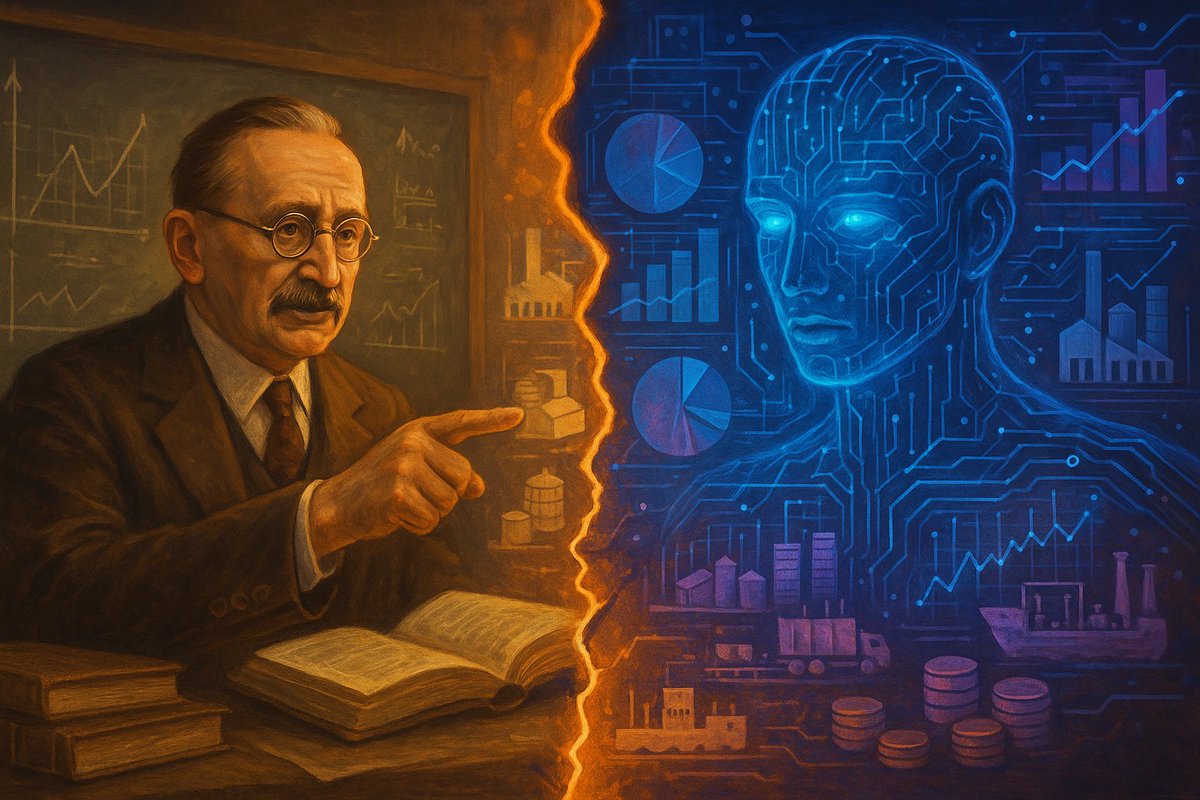

Brilliant economists are saying Hayek was right about the past, but AI changes the game.

"The calculation problem? Solved. Modern supercomputers can handle what Soviet planners couldn't."

Here's why even smart people are missing something fundamental. 🧵

"The calculation problem? Solved. Modern supercomputers can handle what Soviet planners couldn't."

Here's why even smart people are missing something fundamental. 🧵

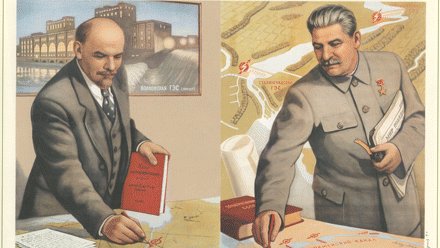

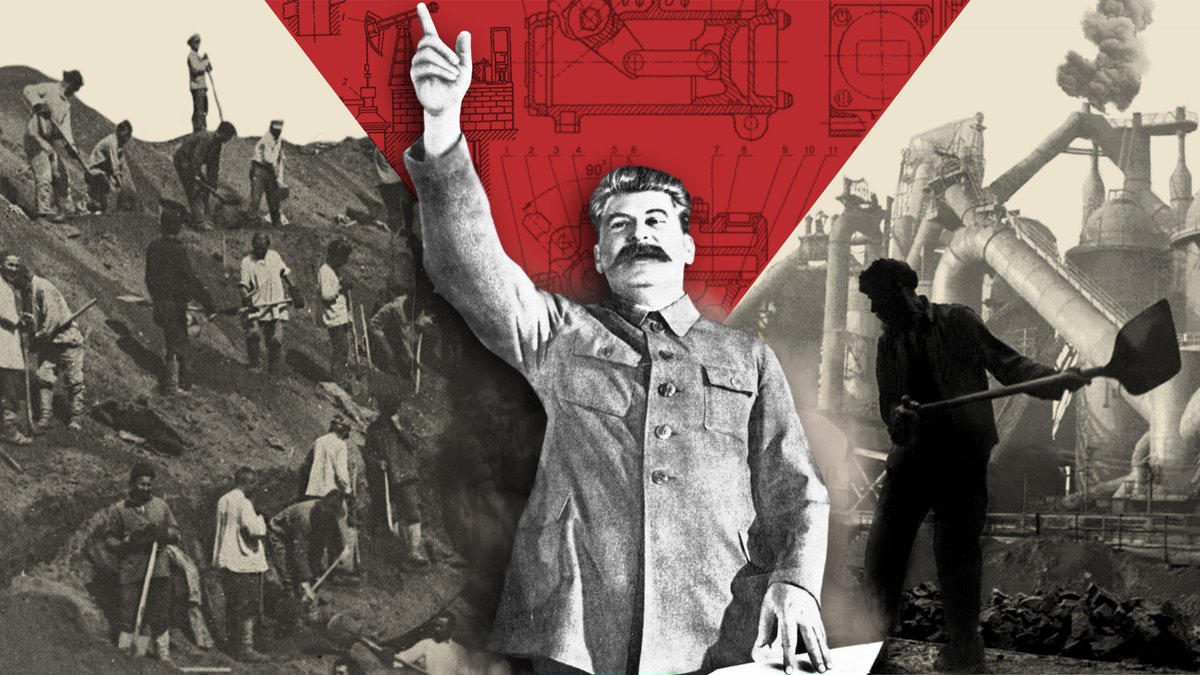

This isn't new thinking. It's the return of an ancient conceit.

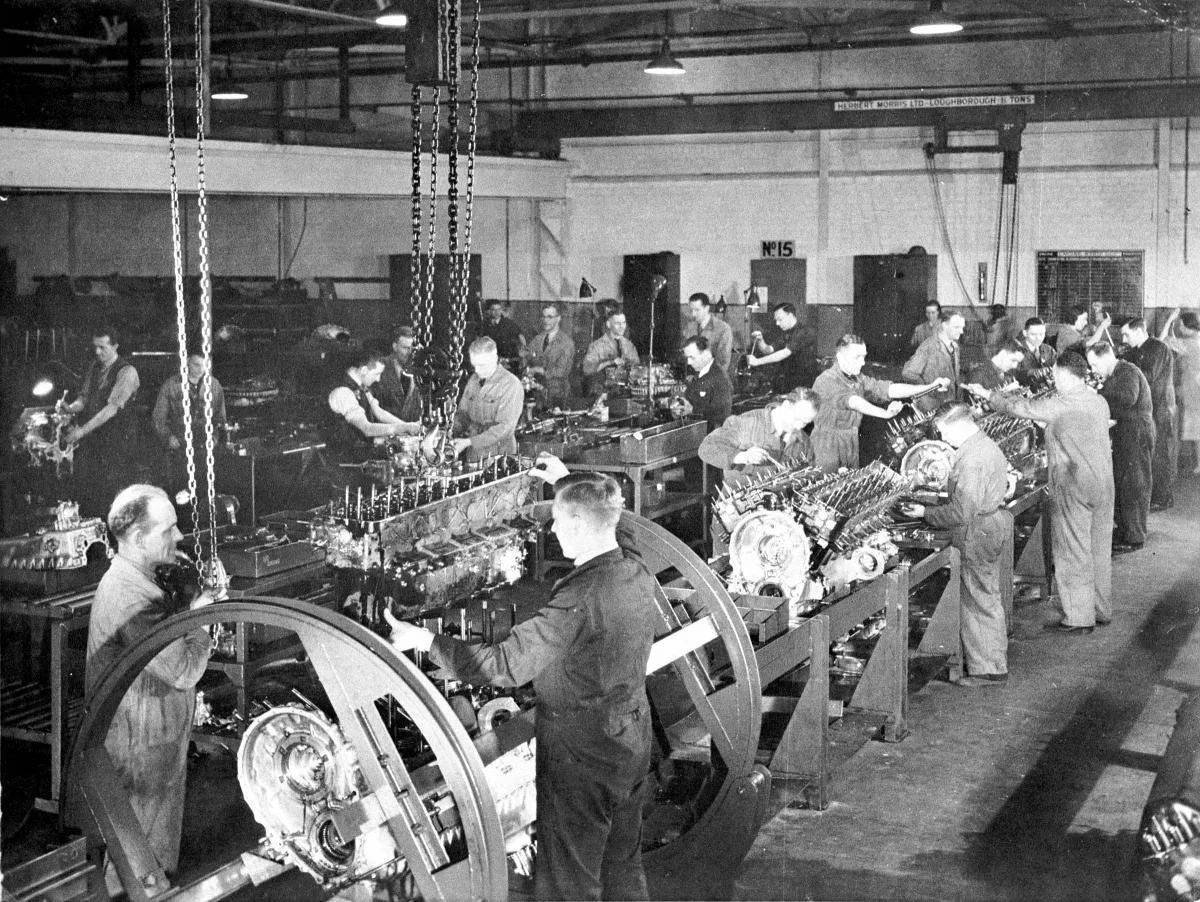

Soviet planners once believed they could organize society "scientifically." No more waste, no unemployment, just rational experts allocating resources perfectly.

They called it scientific socialism. We know how that ended.

Soviet planners once believed they could organize society "scientifically." No more waste, no unemployment, just rational experts allocating resources perfectly.

They called it scientific socialism. We know how that ended.

What these AI evangelists miss is what Friedrich Hayek understood decades ago: the problem was never computational power.

The problem is information itself.

When the price of tin rises, you don't need to know why. You just need to know that tin is now more valuable elsewhere.

The problem is information itself.

When the price of tin rises, you don't need to know why. You just need to know that tin is now more valuable elsewhere.

This is what makes markets miraculous. They coordinate billions of decisions using almost no information.

A price contains everything market participants need to know. Nothing more, nothing less.

The "economy of knowledge," as Hayek called it, operates on radical simplicity.

A price contains everything market participants need to know. Nothing more, nothing less.

The "economy of knowledge," as Hayek called it, operates on radical simplicity.

Economists proved this formally in the 1970s. Competitive markets are "informationally efficient." They use the absolute minimum information possible to achieve optimal outcomes.

No algorithm, no matter how sophisticated, can improve on this. It's mathematically impossible.

No algorithm, no matter how sophisticated, can improve on this. It's mathematically impossible.

But here's the deeper issue that destroys the AI-planning fantasy entirely:

Much of human knowledge can't be articulated at all. It's tacit, experiential, embedded in context that no central system can capture.

How do you program an algorithm to invent the iPhone?

Much of human knowledge can't be articulated at all. It's tacit, experiential, embedded in context that no central system can capture.

How do you program an algorithm to invent the iPhone?

The entrepreneurs imagining breakthrough products, the local knowledge of specific circumstances, the cultural intuitions that drive innovation. None of this can be reduced to data points for an AI system to process.

Central planning fails not because computers aren't fast enough, but because the knowledge problem is unsolvable.

Central planning fails not because computers aren't fast enough, but because the knowledge problem is unsolvable.

Today's AI democracy projects and algorithmic governance systems are just Soviet five-year plans with better graphics.

They promise to engineer away human complexity. But complexity isn't a bug. It's the feature that makes free societies innovative and resilient.

They promise to engineer away human complexity. But complexity isn't a bug. It's the feature that makes free societies innovative and resilient.

The fatal conceit lives on. Every generation thinks it has the technology to finally make central planning work.

But markets don't need to be improved by AI. They need to be protected from the planners who think they can build something better.

But markets don't need to be improved by AI. They need to be protected from the planners who think they can build something better.

Want to learn how to defend these ideas when your professors push the latest version of techno-solutionism?

We built a survival kit that trains you to argue for liberty in hostile classrooms—and win.

👉 go.studentsforliberty.org/college-surviv…

We built a survival kit that trains you to argue for liberty in hostile classrooms—and win.

👉 go.studentsforliberty.org/college-surviv…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh