I'm an academic economist and I've been bullish on crypto for a few years. The thesis is simple. Crypto is a tool almost exclusively for criminals: it's basically useless to anyone in the developed world. But it's a really good tool for criminals

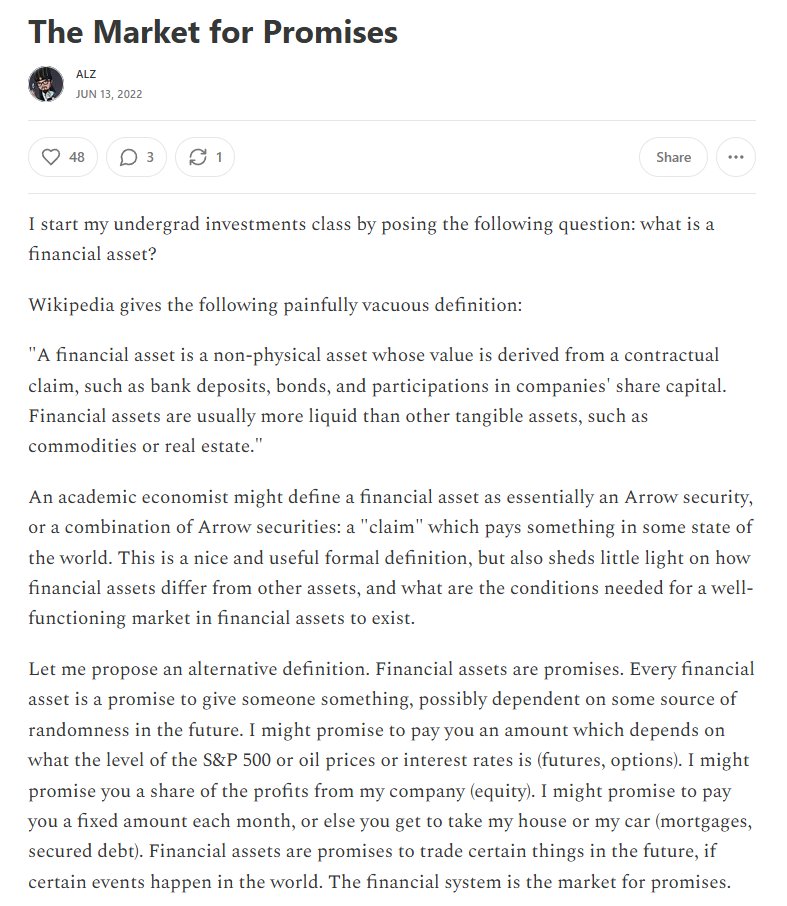

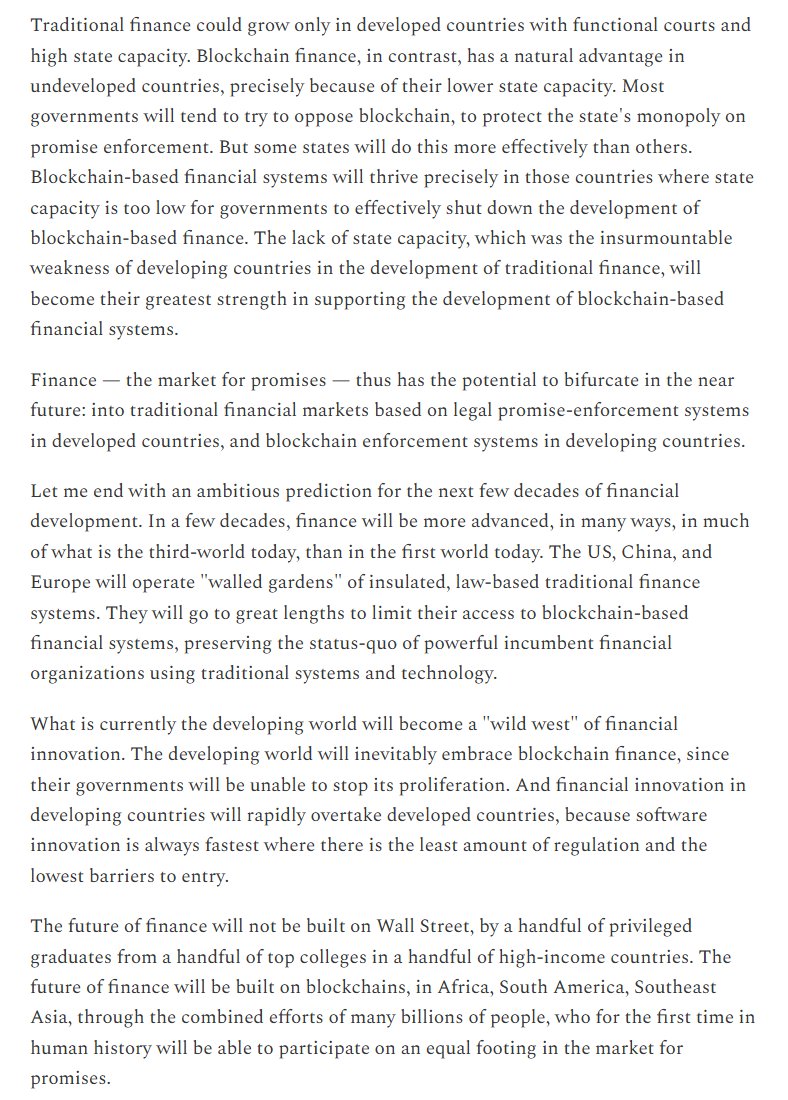

Crypto does, however, link to a very fundamental question: finance, as we know it, is a derivative of legal systems. Finance is the trading of promises, and promises only work when people think they'll be enforced

Finance has historically lived in hubs like NYC, London, Hong Kong, because these places have the state capacity to enforce promises. Finance doesn't meaningfully happen in the developing world, largely because there isn't the state capacity to consistently enforce promises

What is deeply interesting about crypto is that crypto is an alternative promise enforcement system. Anyone with a Starlink in Nigeria or Vietnam or South America has the exact same guarantee of BTC wallet promise enforcement as someone in NYC or London or Hong Kong

I discuss this in a short blog post: should be easy to find on Google, but DM me if you want a link. I ended the post with a really dumb, but potentially interesting, prediction about where crypto - and finance more generally - will go in the next few decades

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh