I think the time has come for me to write my take on @daveckang's entire research ouvre--its strengths and the limitations I find in its central arguments.

I do think that his new piece in IO really rests on ideas and assumptions of this earlier work, even if they are not cited.

I do think that his new piece in IO really rests on ideas and assumptions of this earlier work, even if they are not cited.

Essentially I think all of these books, and the many articles that precede them, are variations on a central theme -- a thesis about Chinese statecraft that extends back several thousand years but is rooted in concerns about the present.

The concern with the present is this: Kang is worried, and has been worried for two decades, about the possibility of war between America and China.

He believes, and has believed for two decades, that this possibility exists mostly because the American side sees things through the militarized lens of zero-sum great power rivalry--a lens which neither the Chinese nor the other countries in Asia share.

I will put aside the empirical question of whether this is an accurate description of how either the Americans or the Chinese thought about things between 2000 and now--the important thing is that this has been the animating concern of Kang's work over the last two decades.

All of Kang's work can be brought back to this question: why do the Americans see a rising China as revanchist power intent on uprooting an American-led global order, with force of arms if necessary when there is not strong evidence that the Chinese are aiming to do this?

@daveckang's answer to this question, in essence, goes like this: the Americans think this way because this is the natural lesson of the history of European/western geopolitics, 1500-1900.

@daveckang For 500 years European leaders warred against each other with special ferocity. The modern (western) bureaucratic state was created by these wars.

@daveckang For most European leaders who ruled between 1400 and 1900. the measure and purpose of a kingdom's public interests was military power. For the strong this meant military domination; for the weak, coalitions to prevent the same.

@daveckang Thus in the European context the story of "the rise and fall of great powers" is the story of mutually hostile and jealous kingdoms vying for universal hegemony.

@daveckang The ultimate arbiter of this contest was military victory and defeat--and thus military power was both the main measure of national power and the focus of great power diplomacy.

@daveckang The USSR and the United States inherited this tradition and during the Cold War globalized it. Their contest folded in more elements of national power (economics, ideology, espionage, etc) but the goals (hegemony) the assumptions (zero sum great power contest) were the same.

@daveckang The main academic field that studies international politics ("international relations"), the academic field that Kang is a member of, began as an attempt to make sense of the origins of WWII and guide policy makers during the Cold War.

This field was strongly influenced by this historical moment. Moreover, the universe of case studies considered under the rubric of "great power relations" were great powers in the western state system, c. 1400-present.

Kang's big idea--that big idea that underlies all of his work--is that the laws of politics and power that identified by his field are the reified lessons of the the European historical experience.

And this history is different from the rest of the world's--especially Asia's.

And this history is different from the rest of the world's--especially Asia's.

In book after book, article after article, Kang has argued the East Asian historical experience is different.

War was not so central to East Asian history.

War was not the primary engine of East Asian state formation.

War between East Asian states was an order of magnitude less common than between European states.

War was not the primary engine of East Asian state formation.

War between East Asian states was an order of magnitude less common than between European states.

Historically East Asians were not motivated by European conceptions of domination and independence.

East Asian states were more comfortable with hierarchy between nations; East Asian leaders did not feel the same need to balance against potential hegemons.

East Asian states were more comfortable with hierarchy between nations; East Asian leaders did not feel the same need to balance against potential hegemons.

East Asian hegemons (read: China) likewise did not have a conception of hegemony or empire that propelled them to invade their neighboring states and exercise imperial control over them. There are only a few exceptions--and they are exceptions, not the norm.

This is more or less Kang's argument. From this perspective the most aggressive episodes of modern East Asian history (Japan, 1895-1945; China, 1949-1979) happened mostly because select East Asian elites adopted Western ideologies to guide their statecraft.

In both cases this was a one or two generation affair that ended in national disaster. Both Japan and China have since reverted to the traditional Asian mean. Now the main exponent of zero-sum, militaristic logic in the region is... the United States.

As Kang sees it, there is something of a natural order to East Asian international relations: China is the hegemon, but it maintains its position through trade and cultural suasion.

In this schema Chinese ambitions are limited to consolidating its regional position and resolving "internal" sovereignty claims (Taiwan, Ladakh, SCS, etc).

Most of the other countries in the region, meanwhile, just want to trade with the Chinese. The great power rivalry lens is imposed entirely from outsiders who share the same cultural imperatives that have led to war and bloodshed for the last 5 centuries of western history.

This is the gist of Dr. Kang's case--the connective tissue that connects all of his papers and books, be they about state building in early modern China or US-China military competition today.

So what do I think of this argument?

I mostly think it suffers from several problems. These are both empirical and conceptual.

I mostly think it suffers from several problems. These are both empirical and conceptual.

What I liked about Kang's work is that takes history seriously, and it takes history not often covered by either western historians or western political scientists seriously.

Kang's larger critique of IR literature--that it draws generalizable laws of human history from an extremely narrow and unrepresentative base of that history--is 1well argued and perfectly on target.

But like I said there are problems. The first are empirical.

I don't want to get into the weeds on the empirical question on twitter--I think a blog post or even a journal article might be the better place for that--but my basic response is that his characterization of East Asian statecraft and statebuilding relies on a narrower base than

base of case studies than I am comfortable with it. I think his claims are not tenable for East Asia before the year 1424 or so. In the 1424-1842 period are only tenable if you restrict the universe of Asian polities to the Ming/Qing, Ryukyu, Joseon, Tokugawa, + Le Dyansty.

Now that is not *nothing*--you will not find any set of European countries with population/wealth levels equivalent to China, Korea, Japan, and Vietnam with the same records of peace over the years 1400-1850.

Explaining this is difficult for traditional western theories of international relations, as well as any realpolitik theory of the state. "Explain why Chinese armies never tried to subject Korea after the Mongol conquests" is a real puzzle these theories cannot answer.

On the flip side, Kang has some trouble explaining why the Qing launched separate foreign invasions of Burma, the Ming's incessant, aggressive wars against the Mongols, both state's treatment of small statelets like Hami, constant advances on the tribal frontier, and so forth.

(There is also a strong argument to be made that warring states Japan and the multiple periods of division within China should 'count' as interstate warfare--especially if things like the 100 years war are put on the European ledger--but that is an argument for a different day).

So I think Kang's historical accounting is correct, but only on very narrow bounds: states run by Confucian officialdoms after the reign of Zhu Di and before the Opium War pries open China and Perry pries open Japan.

(As a side note: it is interesting how some of the historians who are most critical of Kang's past work are historians are the region's this story precludes.

Thus Peter C Perdue, who wrote the definitive history of the Qing conquest of Xinjiang and Tibet, has a ferocious literature review tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.108…

likewise, @JimMillward, one of the premier historians of Uyhgur history and Qing foreign policy in central Asia, has a diametrically opposed understanding of Qing grand strategic thought strategicspace.nbr.org/the-qing-conce…

@JimMillward as well as Chines state building jimmillward.medium.com/we-need-a-new-…

Now again, I am not going to get into the weeds of this on twitter, I will simply note that my read of the history is very different than Kang's. But while all of that is interesting, this historical stuff is something of a sideshow to my real critique.

This critique hits much wider than Kang. It is an implicit critique of every paper that has ever been written with about "strategic culture" as well as much of the historical persistence literature in economics. I think Kang's thesis has a problem that all of them do to.

Kang is essentially arguing "I have identified a historical pattern in human behavior that distinguishes the behavior of some humans from others, and which stretches over centuries."

There are two basic ways you can account for persistent patterns like these.

The first view is that agent's behaviors are determined mostly by incentives and structural constraints.

The first view is that agent's behaviors are determined mostly by incentives and structural constraints.

e.g., if England followed a consistent grand strategic paradigm 1500-1850, it is because over that entire time England faced certain conditions--its own mercantile economy, a sea moat, close proximity to much more populous continental powers--that incentivized it to do so.

The alternative explanation for persistence is based on inheritance: the English followed a similar consistent strategy over 5 centuries because each generation inherited the worldviews, traditions, norms and "culture" of the generation that came before.

This basic division is not always so clear cut in reality (consider the case of a historically persistent domestic institution whose structure both incentivizes certain behavior and which explicitly teaches certain lessons or inculcates certain values) but it useful conceptually.

it is squarely at the center of the debates that divide anthropologists involved in the "cultural evolution" subfield.

On one side are those who believe that most cultural traditions are not so much transmitted generation to generation so much as regenerated in each generation. (Such as @OliverWithAnI )

amzn.to/2PBjH3c

amzn.to/2PBjH3c

On the other side are those who believe that historically persistent behavior is produced by ideas, psychological traits, or practices passed down generation to generation (Such as @JoHenrich)

amzn.to/2LuDcEh

amzn.to/2LuDcEh

If you fall in the second camp you have an additional burden: you must explain *how* idea, traits, and practices are passed down.

There are several ways this could be done.

There are several ways this could be done.

Behavior could be an expression of basic psychological traits, all of which are inherited genetically.

They could be an expression of those traits, all of which are inherited through implicit cultural learning.

They could be an expression of those traits, all of which are inherited through implicit cultural learning.

Behavior could also be downstream explicit concepts, frameworks, and lessons--ideas that can be formally expressed.

These in turn can be taught implicitly (gender norms are a common example here), or taught explicitly (as in military doctrine).

These in turn can be taught implicitly (gender norms are a common example here), or taught explicitly (as in military doctrine).

If you believe that PAST behavior is predicative of FUTURE behavior because this behavior is inherited one generation to another, then you MUST PROPOSE A MECHANISM OF INHERITANCE!

This is my key critique of @daveckang's entire program--as well as all those most theories of strategic culture generally. They ascribe great power to "culture" without explaining what creates that culture generation to generation.

@daveckang Cultural patterns *only* persist if the mechanisms by which the underlying culture is transmitted remain unchanged over long periods of time.

If those mechanisms no longer function, or if their nature changes, so will future behavior.

If those mechanisms no longer function, or if their nature changes, so will future behavior.

@daveckang This is one of the central lessons of both biological evolution & the "cultural evolution" literature in anthropology -- without mechanisms that can reproduce traits with a high degree of fidelity one generation over another, persistence is not possible.

Let me offer two hypothetical mechanisms of transmission in this case and you will understand why this is important.

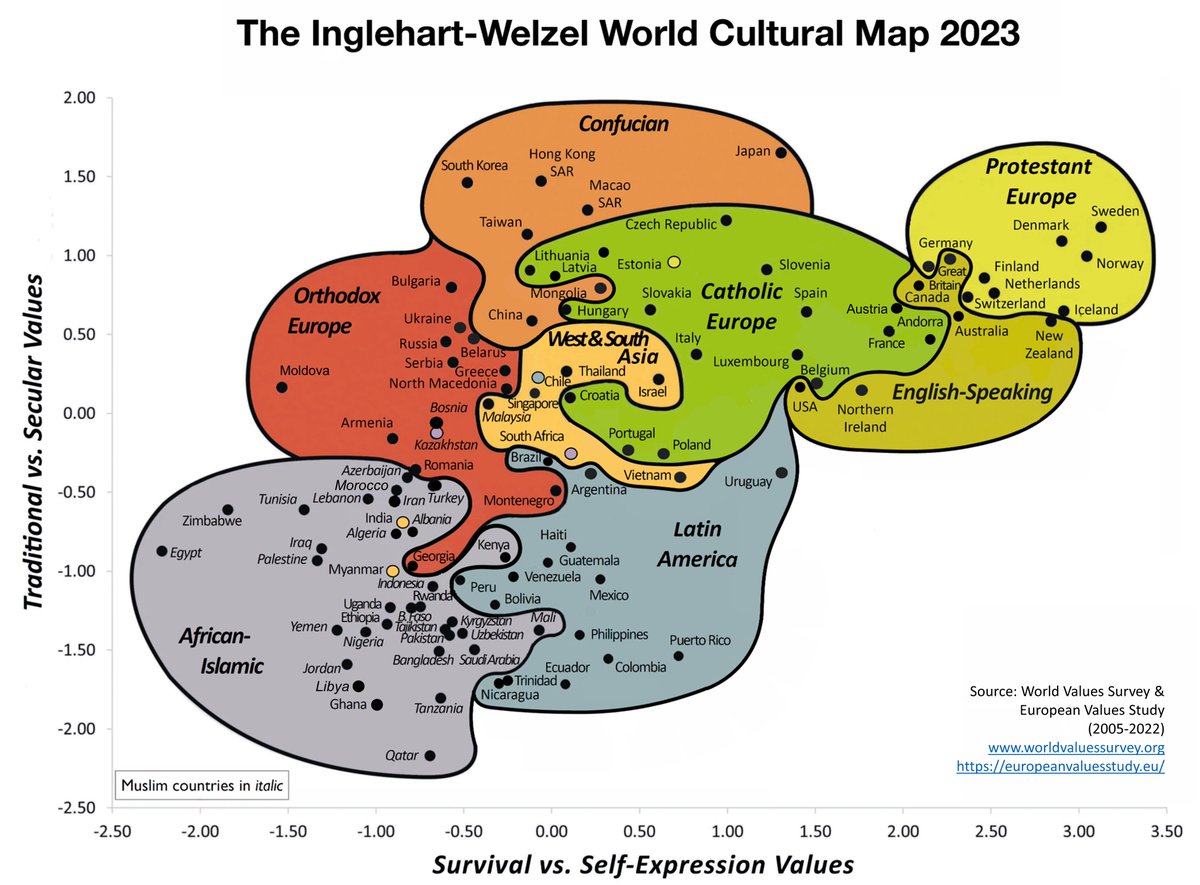

Perhaps people raised in East Asian cultures have a very different set of fundamental values--the sort of values recorded in world values surveys

Or in books like this amazon.com/gp/product/074…

and perhaps those base values shape the way East Asians think about harmony and hierarchy, and maybe those mid-level concepts shape their thinking on international hierarchy and harmony.

This is one answer, though it sort of hand waves the actual mechanism of transmission away to "culture" But it is one model.

But let me offer a different mechanism.

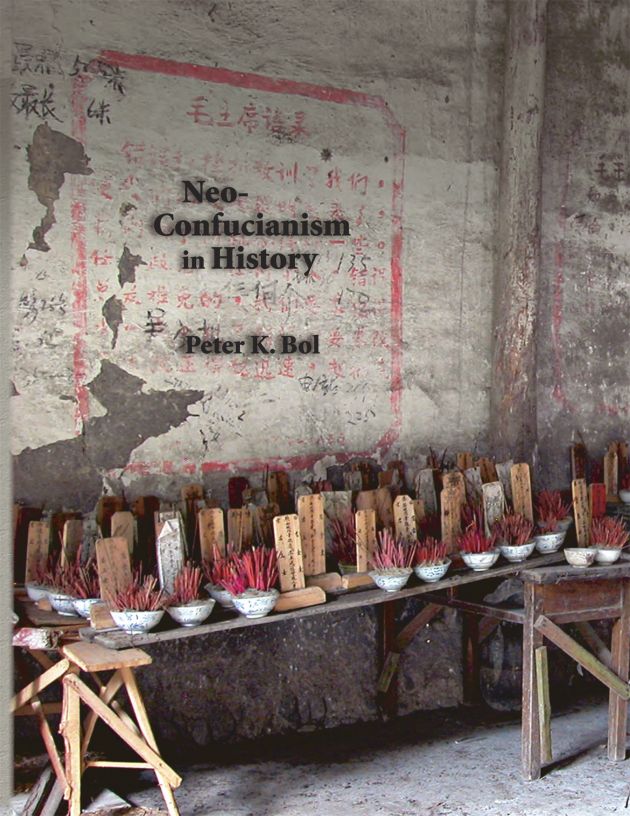

Starting in the Northern Song dynasty Confucian intellectuals pioneered a new intellectual paradigm that explained the relationship between man and the cosmos, as well as the cosmos and the political order.

In English this ideology--a totalizing version of Confucian thought that broke in fundamental ways with older Confucian notions, optimized in some ways to defeat the political and intellectual influence of Buddhism in China--is known as "Neoconfucianism."

This is one of the great transitions in Chinese history.

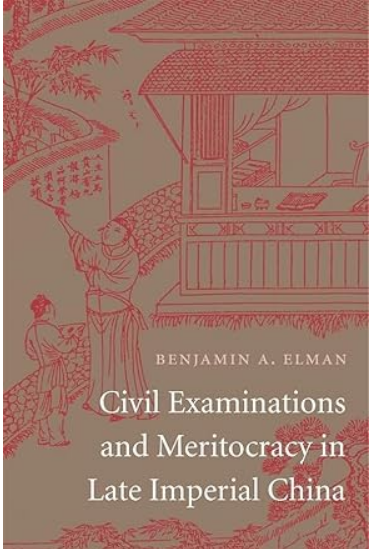

Between this point and the end of the Qing Dynasty, Neoconfucian orthodoxy was the unifying ideology of the Chinese elite. One had to master it in order to pass imperial examinations.

Between this point and the end of the Qing Dynasty, Neoconfucian orthodoxy was the unifying ideology of the Chinese elite. One had to master it in order to pass imperial examinations.

Chinese elites spent decades of their life memorizing the exact words and correct interpretations of the Neoconfucian canon.

It shaped how they viewed the world, and they viewed the Chinese state's position within that world.

It shaped how they viewed the world, and they viewed the Chinese state's position within that world.

And here is the thing, neoconfucian ideas had purchase in other countries too. Which countries?

Korea, almost immediately. The Manchu/Qing state, after they conquered China. Japan (but not under Hideyoshi!). The kingdom of Ryuku. Vietnam.

Korea, almost immediately. The Manchu/Qing state, after they conquered China. Japan (but not under Hideyoshi!). The kingdom of Ryuku. Vietnam.

Some of these kingdoms had formal exam systems patterned after the Chinese one. But in all of then Neoconfucian orthodoxy became one of the strongest, and perhaps dominant, current in elite ideology.

Neoconfucian orthodoxy had some very specific ideas about the relationship between the emperor and the rest of humankind. It was not hard for Chinese officials and leaders/diplomats from these countries to use these ideas to regulate their relationships.

So that is a different cultural theory--a theory that accounts for why the Neoconfucian influenced dynasties of Korea, China, Japan, and Vietnam had comparatively little war--that identifies a fairly narrow but explicit method of cultural transmission.

But the mechanism by which neoconfucianism was transmitted for four hundred years is no more! Chinese officials are not tested on the Four Books, are not expected to know scripture and verse of Zhu Xi, and do not regulate the Chinese polity through Neoconfucian ritual!

China is no longer a neoconfucian state. Nor is Taiwan, Japan, South and North Korea, Vietnam, any other country in SE Asia, no neighboring great powers like Russia and India, nor its great power rival, the United States.

Modern China--its state structures, its education, its popular ideologies--is a mix of 19th century nationalism and scientism, explicit Marxist political frameworks, as well as late 20th century economic and industrial frameworks.

Thrown into this mix is a cultural tradition that stretches back to Confucius--but modern Chinese are just as likely cite the ancient Confucian's enemies as they are their sages, and even their interpretation of the sages mixes non-Neoconfucian readings of the classics.

So, IMHO, it does not make sense to interpret Chinese strategic intentions or the future structure of East Asian international relations on the diplomatic relations of Ming/Qing emperors with the leaders of early modern Korea, Japan, Vietnam, and Ryukyu.

The cultural ideals that governed that relationship from the Chinese side came from a totalizing ideology that every Chinese elite was indoctrinated in from childhood and assessed on across their career. That whole system is gone.

Even at its peak, Chinese statesmen who embodied this worldview were only capable of creating lasting harmony and stable hierarchy when dealing with foreign elites who shared this same framework of ideas.

I am more sympathetic to arguments that the officials of China, whose formative experiences came attracting foreign investment to and guiding the economic development of Chinese counties, cities, and provinces, think of the world in a "win-win" way because of this.

I think that view is wrong--or rather, incomplete--but I find it much easier to defend than the Kang's broader argument, which looks not at the education of China's leaders today, but which points to broad historical patterns from a world long dead.

That is the basic summary of my critique. One day maybe I will work it up into a real academic article; for now you all will have to be satisfied with my thread!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh