The world's most famous neoclassical buildings are kind of boring and generic when you actually look at them.

It's even hard to tell them apart: which one below is Versailles, or Buckingham Palace?

So here's why neoclassical architecture (although it's nice) is overrated:

It's even hard to tell them apart: which one below is Versailles, or Buckingham Palace?

So here's why neoclassical architecture (although it's nice) is overrated:

Buckingham Palace, despite being one of the world's most famous and visited buildings, is essentially quite boring and uninspiring from the outside.

There's a certain stateliness to it, but (like most big neoclassical buildings) it's really just a box wrapped in pilasters.

There's a certain stateliness to it, but (like most big neoclassical buildings) it's really just a box wrapped in pilasters.

The same is true of Versailles.

Again, it's evidently pretty (largely thanks to the colour of its stone) but there's something weirdly plain about it, almost standardised.

Plus the emphasis on its horizontal lines makes it feel very low-lying, undramatic, and flat.

Again, it's evidently pretty (largely thanks to the colour of its stone) but there's something weirdly plain about it, almost standardised.

Plus the emphasis on its horizontal lines makes it feel very low-lying, undramatic, and flat.

This also goes for the White House; it is, despite its fame, a plain building.

Though, of course, it was always supposed to be more of a humble residence than a palace.

Thus the White House represents neoclassical architecture at its most restrained — and, therefore, its best.

Though, of course, it was always supposed to be more of a humble residence than a palace.

Thus the White House represents neoclassical architecture at its most restrained — and, therefore, its best.

Neoclassical architecture can be incredibly impressive; that explains, in part, its immense popularity.

Whether for terraced houses, united to create a harmonious whole with their simple but pleasing proportions, or for grand public buildings with towering colonnades.

It works.

Whether for terraced houses, united to create a harmonious whole with their simple but pleasing proportions, or for grand public buildings with towering colonnades.

It works.

And, of course, "neoclassical architecture" is an incredibly broad term.

It includes everything from the exuberance of Baroque to the regimented simplicity of Georgian, from capital N Neoclassicism (things Romans or Greeks might have built themselves) to elegant Palladianism:

It includes everything from the exuberance of Baroque to the regimented simplicity of Georgian, from capital N Neoclassicism (things Romans or Greeks might have built themselves) to elegant Palladianism:

But what all these substyles are united by is their general adherence to the rules and motifs of original classical architecture, i.e. the architecture of the Ancient Greeks and Romans.

Therein lies their beauty... and also their most fundamental flaws.

Therein lies their beauty... and also their most fundamental flaws.

See, the rules of neoclassical architecture — though they lead to its pleasing proportions, human scale, and unity — are inflexible, especially when it comes to proportion and overall plan.

This explains why neoclassical buildings frequently look so similar:

This explains why neoclassical buildings frequently look so similar:

Along with strict proportions, symmetry is also demanded by the rules of the neoclassical.

But, from faces to flowers and films to photos, absolute symmetry rarely equates to beauty or charm.

And yet all neoclassical buildings are, necessarily, precisely symmetrical.

But, from faces to flowers and films to photos, absolute symmetry rarely equates to beauty or charm.

And yet all neoclassical buildings are, necessarily, precisely symmetrical.

This enforced standardisation is a bigger problem with decoration.

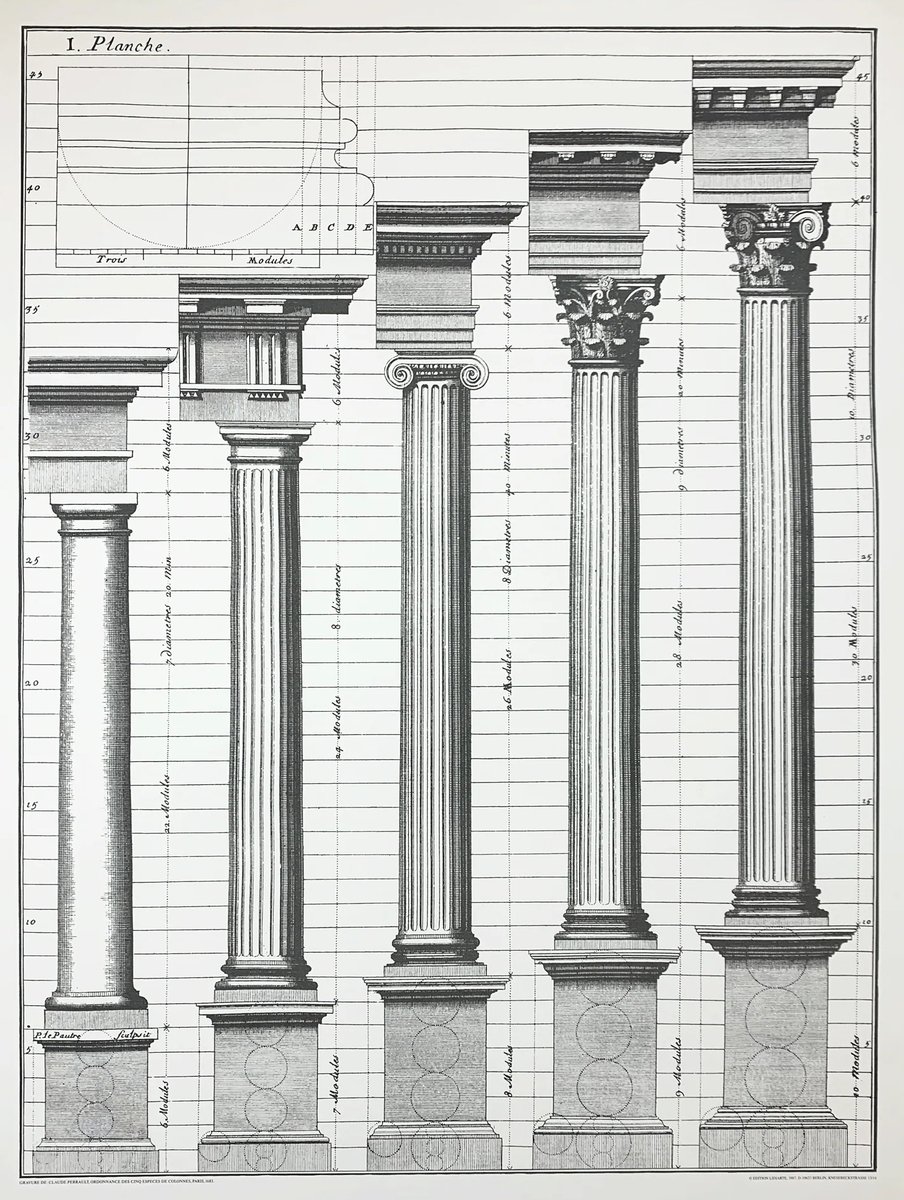

Just think of the famous five classical orders.

Though there is sometimes experimentation, neoclassical buildings rarely stray from the strict rules that govern the decorative details of these five.

Just think of the famous five classical orders.

Though there is sometimes experimentation, neoclassical buildings rarely stray from the strict rules that govern the decorative details of these five.

Hence neoclassical buildings around the world have the same decoration: the same volutes, acanthus leaves, and strings of fruit.

This does create a sense of unity (plus they're pretty!) — but it also feels lifeless, and has no relevance to local heritage.

Always the same.

This does create a sense of unity (plus they're pretty!) — but it also feels lifeless, and has no relevance to local heritage.

Always the same.

And so neoclassical decoration is conventionalised.

A convention is something you do because it's the way you're "supposed" to do it, not because you actually believe in, like, or understand it.

These Corinthian capitals (all from different buildings) lack real meaning or life.

A convention is something you do because it's the way you're "supposed" to do it, not because you actually believe in, like, or understand it.

These Corinthian capitals (all from different buildings) lack real meaning or life.

And all this taken together explains why neoclassical architecture can sometimes feel cold, generic, and boring.

In some ways, it has a lot in common with the monotonous, standardised, box-shaped forms of modern architecture.

In some ways, it has a lot in common with the monotonous, standardised, box-shaped forms of modern architecture.

Just compare it with Gothic or Neo-Gothic Architecture, which are far more varied and alive.

No two Gothic buildings look the same; they are, in both their minutest details and overall shape, fundamentally different.

Because Gothic relies on principles, not rules.

No two Gothic buildings look the same; they are, in both their minutest details and overall shape, fundamentally different.

Because Gothic relies on principles, not rules.

Thus writers like Ruskin and Morris called for a Gothic Revival in the 19th century — they admired its adaptability, responsiveness to local heritage, and general variety.

The ultimate Gothic Revival building is Neuschwanstein Castle; more striking than any neoclassical palace.

The ultimate Gothic Revival building is Neuschwanstein Castle; more striking than any neoclassical palace.

There are five classical orders, but more than five thousand Gothic orders — because Gothic has no decorative rules and changes depending on the artist responsible for carving each of its decorations.

Hence the Gothic reflects the lives of the people who made these buildings.

Hence the Gothic reflects the lives of the people who made these buildings.

And nor does Gothic demand symmetry or standardisation; buildings can have all manner of form and layout, with towers of varying height or design and windows of different shape and scale.

Notice how many Gothic buildings, whether castles or cathedral, have asymmetrical towers.

Notice how many Gothic buildings, whether castles or cathedral, have asymmetrical towers.

London (for example) is filled with hundreds of buildings, particularly Neo-Gothic, that are far more interesting than Buckingham Palace.

St Pancras Station, the Royal Courts of Justice, or even Tower Bridge have a kind of liveliness and drama that neoclassical design lacks.

St Pancras Station, the Royal Courts of Justice, or even Tower Bridge have a kind of liveliness and drama that neoclassical design lacks.

Nor does neoclassical urban design — which favours gridded streets and wide boulevards — lead to the winding alleys, deep eaves, and steep gables that make Medieval cities so charming and curious.

Simplicity is a virtue, but simplicity alone does not make a city beautiful.

Simplicity is a virtue, but simplicity alone does not make a city beautiful.

The only thing that saves the Houses of Parliament in London from being boring are its three asymmetrical towers, especially Big Ben.

You don't get that kind of asymmetry with neoclassical design, and yet this is what makes the Houses of Parliament so immediately recognisable:

You don't get that kind of asymmetry with neoclassical design, and yet this is what makes the Houses of Parliament so immediately recognisable:

It's impossible to deny that neoclassical architecture can be both lovely (for simple houses) or grand (for public buildings).

But it's a shame that the words "traditional architecture" have been narrowed down in the minds of most people to refer exclusively to neoclassical.

But it's a shame that the words "traditional architecture" have been narrowed down in the minds of most people to refer exclusively to neoclassical.

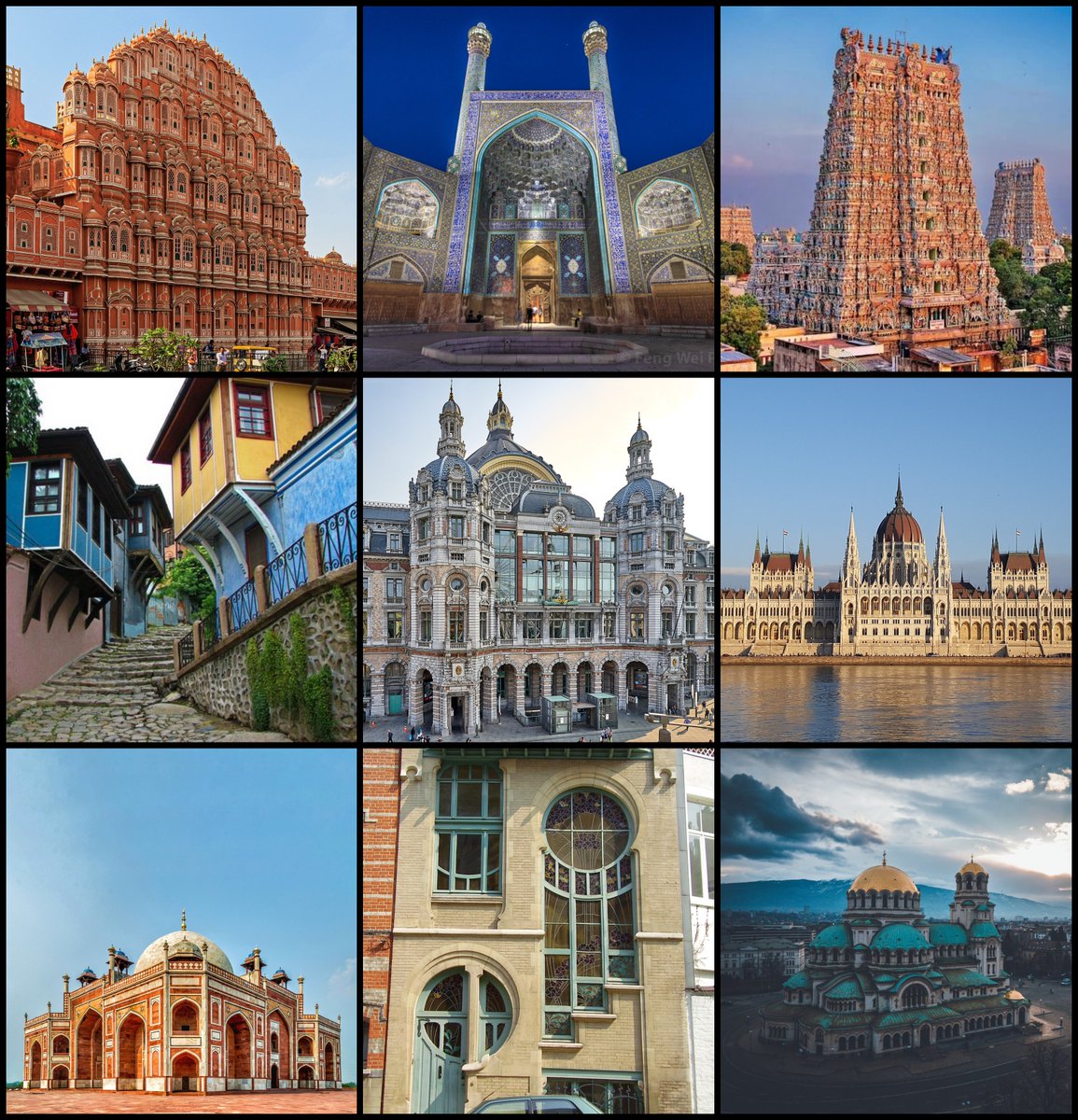

The whole world is a treasury of wonderful architectural styles bequeathed to us by our ancestors, tested for beauty and charm by the tastes of the centuries, and crying out to be emulated in the present day, from Mughal to Safavid to Byzantine to Romanesque and beyond:

And, crucially, the relationship between these sorts of buildings and the places they stand — local history, culture, heritage — is much stronger.

The best architecture says something about its region and the people who built it; this is partly why tourists love old buildings.

The best architecture says something about its region and the people who built it; this is partly why tourists love old buildings.

And, otherwise, there are dozens of architectural styles that offer far more interesting possibilities than neoclassical ever could.

Look at the colour, liveliness, and variety of Art Nouveau or Art Deco, for example; there's just so much more going on here:

Look at the colour, liveliness, and variety of Art Nouveau or Art Deco, for example; there's just so much more going on here:

Sometimes we need the restrained elegance of neoclassical architecture, whether for ordinary houses or grand public buildings.

But the world needs more than restrained elegance; and, equally, the term "traditional architecture" needs to mean much more than just neoclassical.

But the world needs more than restrained elegance; and, equally, the term "traditional architecture" needs to mean much more than just neoclassical.

If you enjoyed this you'll like my new book.

It's an introduction to culture — art, architecture, history, literature — framed as an alternative to the 24 hour content cycle.

You can pre-order at the link in my bio — and get 25% off at Waterstones with the code CULTURAL25!

It's an introduction to culture — art, architecture, history, literature — framed as an alternative to the 24 hour content cycle.

You can pre-order at the link in my bio — and get 25% off at Waterstones with the code CULTURAL25!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh