Did you know Polish 🇵🇱 cuisine is just as rich, refined, and sophisticated as Italian, Japanese, or French?

For centuries, it has produced dishes of depth, elegance, and variety. Poland has a culinary heritage that matches the great kitchens of the world.

Thread 🧵

For centuries, it has produced dishes of depth, elegance, and variety. Poland has a culinary heritage that matches the great kitchens of the world.

Thread 🧵

1/ Kiszone ogórki – Salted dill cucumbers

Fermented cucumbers brined with dill, garlic, and horseradish. Their sour-salty crunch is both peasant food and noble table staple. Fermentation was historically vital in Poland to preserve vegetables through harsh winters.

Fermented cucumbers brined with dill, garlic, and horseradish. Their sour-salty crunch is both peasant food and noble table staple. Fermentation was historically vital in Poland to preserve vegetables through harsh winters.

2/ Oscypek z grilla – Grilled oscypek cheese

A smoked sheep’s cheese from the Tatra mountains, grilled and often served with cranberry jam. It dates back to the 15th century pastoral culture of the Podhale highlanders. Recognized by the EU as a protected regional product.

A smoked sheep’s cheese from the Tatra mountains, grilled and often served with cranberry jam. It dates back to the 15th century pastoral culture of the Podhale highlanders. Recognized by the EU as a protected regional product.

3/ Kiełbasa krakowska – Kraków sausage

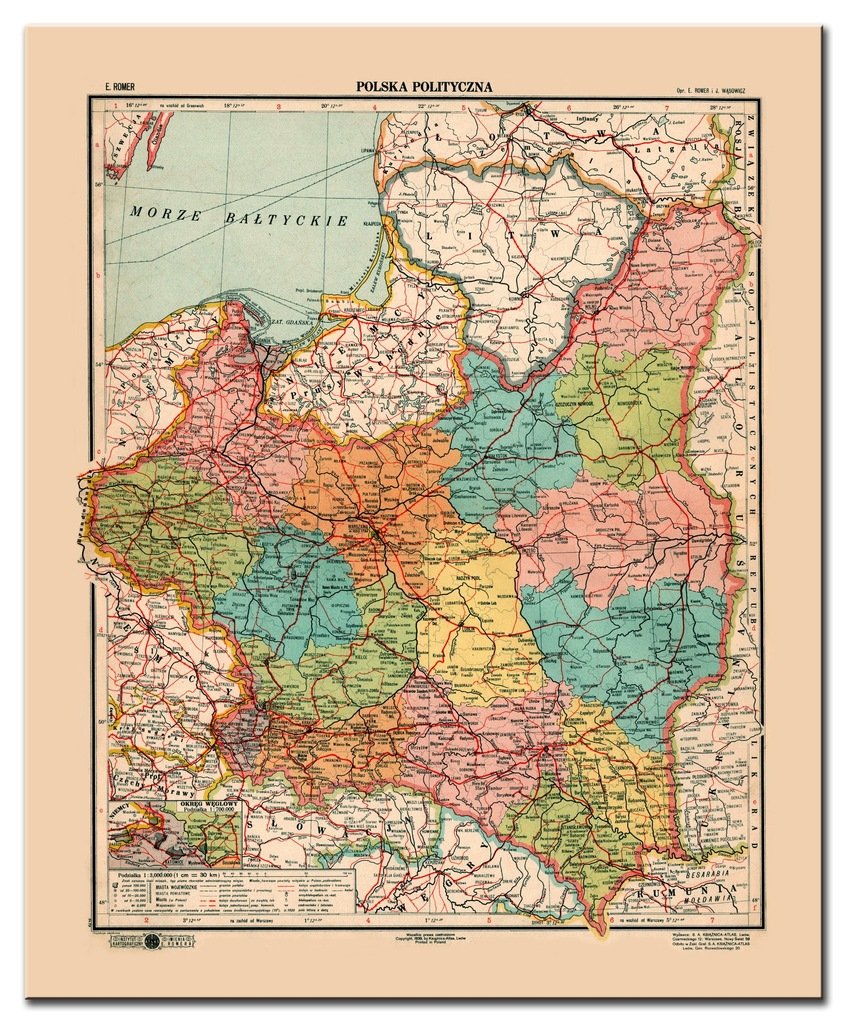

A dry, smoked sausage from Kraków, peppery and garlic-rich, traditionally eaten cold and sliced. Its recipe developed in the 19th century, when Kraków was part of Austrian Galicia and enjoyed a reputation for refined meat products.

A dry, smoked sausage from Kraków, peppery and garlic-rich, traditionally eaten cold and sliced. Its recipe developed in the 19th century, when Kraków was part of Austrian Galicia and enjoyed a reputation for refined meat products.

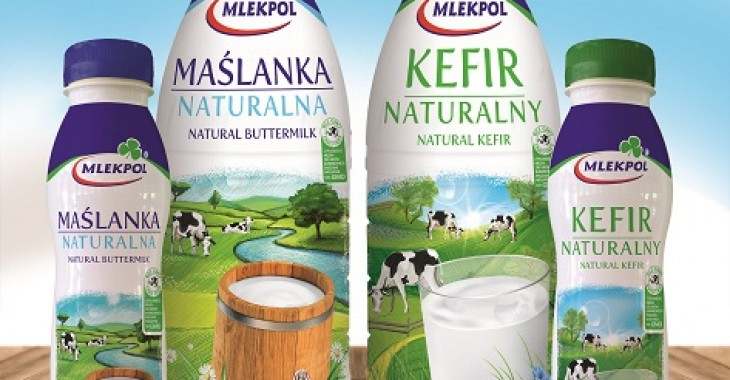

4/ Chłodnik litewski – Lithuanian cold beet soup

Cold soup made with beets, kefir, cucumber, dill, and eggs. It reflects the Grand Duchy of Lithuania’s culinary heritage, absorbed into Polish cuisine during the centuries of the Commonwealth. Popular as a refreshing summer dish.

Cold soup made with beets, kefir, cucumber, dill, and eggs. It reflects the Grand Duchy of Lithuania’s culinary heritage, absorbed into Polish cuisine during the centuries of the Commonwealth. Popular as a refreshing summer dish.

5/ Kefir i maślanka – Kefir and buttermilk

Fermented dairy drinks, tangy and refreshing. Kefir comes from Caucasian traditions brought to Poland in the 19th century, while buttermilk is a byproduct of butter-making, long valued as a cheap, healthy farmer’s drink.

Fermented dairy drinks, tangy and refreshing. Kefir comes from Caucasian traditions brought to Poland in the 19th century, while buttermilk is a byproduct of butter-making, long valued as a cheap, healthy farmer’s drink.

6/ Śledzie – Herring

Pickled herring in oil, sour cream, or vinegar with onion and apple. A centuries-old Polish classic, rooted in Catholic fasting traditions, where meat was forbidden on Fridays and during Advent or Lent. It became central to Christmas Eve (Wigilia) tables.

Pickled herring in oil, sour cream, or vinegar with onion and apple. A centuries-old Polish classic, rooted in Catholic fasting traditions, where meat was forbidden on Fridays and during Advent or Lent. It became central to Christmas Eve (Wigilia) tables.

7/ Żurek – Sour rye soup

Made with a fermented rye starter (zakwas), served with sausage, potatoes, and boiled egg. It is the quintessential Easter soup, symbolizing rebirth through fermentation. Its origins trace back to medieval Poland, where sour soups were everyday fare.

Made with a fermented rye starter (zakwas), served with sausage, potatoes, and boiled egg. It is the quintessential Easter soup, symbolizing rebirth through fermentation. Its origins trace back to medieval Poland, where sour soups were everyday fare.

8/ Barszcz czerwony – Red borscht

Clear beetroot soup, served with dumplings (uszka). A Christmas Eve must. Beets were cultivated in Poland since the Middle Ages, and barszcz in its modern form became a noble specialty by the 16th century.

Clear beetroot soup, served with dumplings (uszka). A Christmas Eve must. Beets were cultivated in Poland since the Middle Ages, and barszcz in its modern form became a noble specialty by the 16th century.

9/ Rosół – Polish broth

Clear broth with noodles, made from chicken or beef. The iconic Sunday soup, a remedy for colds and fatigue. Its name derives from rosić (to sprinkle, moisten), referring to meat preserved in brine before cooking.

Clear broth with noodles, made from chicken or beef. The iconic Sunday soup, a remedy for colds and fatigue. Its name derives from rosić (to sprinkle, moisten), referring to meat preserved in brine before cooking.

10/ Zupa ogórkowa – Sour cucumber soup

Made from brined cucumbers and pickle juice, with potatoes and cream. Distinctly Polish, tied to the national passion for fermented foods.

Made from brined cucumbers and pickle juice, with potatoes and cream. Distinctly Polish, tied to the national passion for fermented foods.

11/ Kwaśnica – Highland sauerkraut soup

From the Tatra highlands, made with sauerkraut and smoked meats. Different from kapuśniak: sharper, thinner, more rustic. Traditionally eaten by shepherds in Podhale.

From the Tatra highlands, made with sauerkraut and smoked meats. Different from kapuśniak: sharper, thinner, more rustic. Traditionally eaten by shepherds in Podhale.

12/ Zupa grzybowa – Mushroom soup

Forest mushroom soup, often served on Christmas Eve. Mushrooms were a sacred food in Slavic paganism, and the tradition carried into Christian ritual meals.

Forest mushroom soup, often served on Christmas Eve. Mushrooms were a sacred food in Slavic paganism, and the tradition carried into Christian ritual meals.

13/ Pierogi – Polish dumplings

Boiled or fried dumplings with fillings: potato & cheese, sauerkraut & mushrooms, minced meat, or seasonal fruits. First mentioned in Poland in the 13th century. Today, the most famous Polish dish worldwide.

Boiled or fried dumplings with fillings: potato & cheese, sauerkraut & mushrooms, minced meat, or seasonal fruits. First mentioned in Poland in the 13th century. Today, the most famous Polish dish worldwide.

14/ Bigos – Hunter’s stew

A slow-cooked mix of sauerkraut, fresh cabbage, meat, sausage, and mushrooms. Known as early as the 16th century in noble kitchens. Mickiewicz in Pan Tadeusz immortalized it as “the master of Polish stews.”

A slow-cooked mix of sauerkraut, fresh cabbage, meat, sausage, and mushrooms. Known as early as the 16th century in noble kitchens. Mickiewicz in Pan Tadeusz immortalized it as “the master of Polish stews.”

15/ Kotlet schabowy – Breaded pork cutlet

Poland’s version of the schnitzel, introduced in the 19th century under Austrian influence. Served with potatoes and sauerkraut. Became the default Polish Sunday dinner.

Poland’s version of the schnitzel, introduced in the 19th century under Austrian influence. Served with potatoes and sauerkraut. Became the default Polish Sunday dinner.

16/ Placki ziemniaczane – Potato pancakes

Grated potatoes fried into thin cakes. They arrived in Poland in the 19th century with the spread of potatoes, quickly becoming peasant staples. Served with cream, sugar, or meaty sauces.

Grated potatoes fried into thin cakes. They arrived in Poland in the 19th century with the spread of potatoes, quickly becoming peasant staples. Served with cream, sugar, or meaty sauces.

17/ Kopytka – “Little hooves” dumplings

Potato dumplings shaped like hooves, eaten with gravy or butter. A thrifty way to use leftover potatoes, common since the 18th century.

Potato dumplings shaped like hooves, eaten with gravy or butter. A thrifty way to use leftover potatoes, common since the 18th century.

18/ Pyzy – Potato dumplings

Large, soft dumplings, sometimes filled with meat or cracklings. In Warsaw, pyzy were once sold by street vendors from wooden barrels.

Large, soft dumplings, sometimes filled with meat or cracklings. In Warsaw, pyzy were once sold by street vendors from wooden barrels.

19/ Zrazy wołowe – Beef rolls

Thin slices of beef rolled around cucumber, bacon, and onion, simmered until tender. A dish of the Polish-Lithuanian nobility, mentioned in 17th-century cookbooks.

Thin slices of beef rolled around cucumber, bacon, and onion, simmered until tender. A dish of the Polish-Lithuanian nobility, mentioned in 17th-century cookbooks.

20/ Żeberka – Pork ribs

Slow-baked or braised ribs, glazed with honey or beer. Rustic and rich, part of the long Polish tradition of roasting pork.

Slow-baked or braised ribs, glazed with honey or beer. Rustic and rich, part of the long Polish tradition of roasting pork.

21/ Sandacz – Zander (pike-perch)

A freshwater fish prized in Polish lakes and rivers. Delicate, white flesh, usually pan-fried or baked with butter and dill. In old Polish cuisine, zander was considered a noble fish, often served at aristocratic feasts since the 17th century.

A freshwater fish prized in Polish lakes and rivers. Delicate, white flesh, usually pan-fried or baked with butter and dill. In old Polish cuisine, zander was considered a noble fish, often served at aristocratic feasts since the 17th century.

22/ Karp – Carp

The centerpiece of the Polish Christmas Eve (Wigilia) table. Traditionally fried or served in aspic. Carp farming in Poland dates back to medieval monastic ponds of the 13th–14th centuries.

The centerpiece of the Polish Christmas Eve (Wigilia) table. Traditionally fried or served in aspic. Carp farming in Poland dates back to medieval monastic ponds of the 13th–14th centuries.

23/ Pstrąg wędzony – Smoked trout

Trout farming in Poland dates back to the 12th–13th centuries in monastic ponds, making it one of the earliest cultivated fish in Central Europe.

Trout farming in Poland dates back to the 12th–13th centuries in monastic ponds, making it one of the earliest cultivated fish in Central Europe.

24/ Makowiec – Poppy seed roll

Sweet yeast roll filled with poppy seeds, honey, nuts, and raisins. Deeply symbolic at Christmas, where poppy seeds represented fertility and prosperity in old Slavic rituals.

Sweet yeast roll filled with poppy seeds, honey, nuts, and raisins. Deeply symbolic at Christmas, where poppy seeds represented fertility and prosperity in old Slavic rituals.

25/ Sernik – Twaróg heesecake

Made with twaróg (Polish curd cheese), dense and creamy. Baked since at least the 17th century, popularized in monasteries.

Made with twaróg (Polish curd cheese), dense and creamy. Baked since at least the 17th century, popularized in monasteries.

26/ Pączki – Filled doughnuts

Fried yeast dough filled with rose jam or plum butter. Known since the Middle Ages, once made with pork fat inside. Today eaten especially on Fat Thursday.

Fried yeast dough filled with rose jam or plum butter. Known since the Middle Ages, once made with pork fat inside. Today eaten especially on Fat Thursday.

27/ Faworki – Angel wings

Thin, fried pastries dusted with powdered sugar. Eaten at carnival before Lent fasting. Their name comes from the French faveur (ribbon).

Thin, fried pastries dusted with powdered sugar. Eaten at carnival before Lent fasting. Their name comes from the French faveur (ribbon).

28/ Pierniki toruńskie – Toruń gingerbread

Spiced honey cakes from Toruń, baked since the 14th century. Once exported across Europe, rivaling Nuremberg gingerbread.

Spiced honey cakes from Toruń, baked since the 14th century. Once exported across Europe, rivaling Nuremberg gingerbread.

29/ Szarlotka – Apple pie

Apple pie layered with cinnamon apples. Apples are central to Polish orchards since the Middle Ages, especially in Mazovia.

Apple pie layered with cinnamon apples. Apples are central to Polish orchards since the Middle Ages, especially in Mazovia.

30/ Racuchy – Apple fritters

Small pancakes fried with apple slices. Cheap peasant dessert, still a childhood favorite.

Small pancakes fried with apple slices. Cheap peasant dessert, still a childhood favorite.

31/ Sękacz – Tree cake

A spit cake shaped like tree rings, baked over an open fire. Ceremonial in Lithuania and Podlasie.

A spit cake shaped like tree rings, baked over an open fire. Ceremonial in Lithuania and Podlasie.

32/ Karpatka – Carpathian cream cake

Two choux pastry layers filled with custard cream, ridged like mountain peaks of the Carpathians. A 20th-century invention, but already a classic.

Two choux pastry layers filled with custard cream, ridged like mountain peaks of the Carpathians. A 20th-century invention, but already a classic.

33/ Miodownik – Honey cake

Layer cake made with honeyed dough and cream. Honey has been central to Polish sweets since medieval times, when sugar was rare.

Layer cake made with honeyed dough and cream. Honey has been central to Polish sweets since medieval times, when sugar was rare.

34/ Orzechowiec – Walnut cake

Layer cake filled with walnuts, cream, and caramel. Traditional in southern Poland, often made for weddings.

Layer cake filled with walnuts, cream, and caramel. Traditional in southern Poland, often made for weddings.

35/ La Tarte Tropézienne – “Tropézienne tart”

Brioche cake with cream, invented in Saint-Tropez in 1955 by Alexandre Micka, a Polish baker. He used his grandmother’s Polish cream cake recipe.

Brioche cake with cream, invented in Saint-Tropez in 1955 by Alexandre Micka, a Polish baker. He used his grandmother’s Polish cream cake recipe.

36/ Baba au rhum – Rum baba

Yeast cake soaked in rum syrup. Invented in France by exiled Polish king Stanisław Leszczyński in the 18th century. Originally derived from Polish babka drożdżowa. The king found the cake a bit "dry" for his taste.

Yeast cake soaked in rum syrup. Invented in France by exiled Polish king Stanisław Leszczyński in the 18th century. Originally derived from Polish babka drożdżowa. The king found the cake a bit "dry" for his taste.

37/ Beza – Meringue

Meringue cake, crisp outside, soft inside, layered with cream. Though French in origin, it became fully naturalized in Polish patisseries.

Meringue cake, crisp outside, soft inside, layered with cream. Though French in origin, it became fully naturalized in Polish patisseries.

38/ Kremówka – Cream slice

Custard cream cake between two layers of puff pastry. Became famous when Pope John Paul II recalled it as his youth favorite from Wadowice.

Custard cream cake between two layers of puff pastry. Became famous when Pope John Paul II recalled it as his youth favorite from Wadowice.

39/ Ptysie – Cream puffs

Choux pastry filled with whipped cream or custard. A café staple since the 19th century, alongside coffee.

Choux pastry filled with whipped cream or custard. A café staple since the 19th century, alongside coffee.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh