The Battle of Long Island Begins

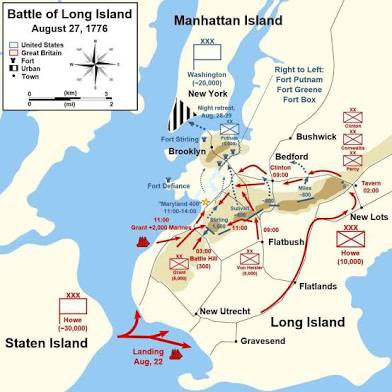

1/ On this day, August 26, 1776, skirmishes sparked the Battle of Long Island, fought fully on August 27 in Brooklyn, New York—the first major clash after the Declaration of Independence. Gen. George Washington’s 10,000 patriots faced British Gen. William Howe’s 20,000 troops. The battle cost ~2,400 casualties, a crushing American defeat that lost New York City. This thread details the Revolutionary War’s context, the battle’s chaos, and its legacy—a pivotal setback that tested the young nation’s resolve.

1/ On this day, August 26, 1776, skirmishes sparked the Battle of Long Island, fought fully on August 27 in Brooklyn, New York—the first major clash after the Declaration of Independence. Gen. George Washington’s 10,000 patriots faced British Gen. William Howe’s 20,000 troops. The battle cost ~2,400 casualties, a crushing American defeat that lost New York City. This thread details the Revolutionary War’s context, the battle’s chaos, and its legacy—a pivotal setback that tested the young nation’s resolve.

Background

2/ By 1776, the American Revolution escalated after Lexington and Concord (1775). The Declaration of Independence (July 4) defied Britain, prompting a massive response. British strategy targeted New York City, a Loyalist stronghold and port, to crush rebellion. Howe landed 32,000 troops (including Hessians) on Staten Island by July. Washington, expecting attack, fortified Brooklyn Heights with 10,000 men—Continentals and militia—while skirmishing on Long Island. British naval dominance and manpower set a daunting stage for the war’s largest battle yet.

2/ By 1776, the American Revolution escalated after Lexington and Concord (1775). The Declaration of Independence (July 4) defied Britain, prompting a massive response. British strategy targeted New York City, a Loyalist stronghold and port, to crush rebellion. Howe landed 32,000 troops (including Hessians) on Staten Island by July. Washington, expecting attack, fortified Brooklyn Heights with 10,000 men—Continentals and militia—while skirmishing on Long Island. British naval dominance and manpower set a daunting stage for the war’s largest battle yet.

Prelude and Skirmishes on August 26

3/ On August 22, Howe landed 15,000 troops on Long Island’s Gravesend Bay, advancing toward Brooklyn. By August 26, British scouts probed American outposts at Flatbush and Red Hook, sparking skirmishes. American riflemen under Col. Samuel Atlee engaged Hessian advance guards, losing ~50 men in brief clashes. Washington reinforced Brooklyn with 3,000 troops, expecting a frontal assault. Howe, however, planned a flanking maneuver via Jamaica Pass, setting up the main battle. August 26’s actions drew both armies into a fateful collision.

3/ On August 22, Howe landed 15,000 troops on Long Island’s Gravesend Bay, advancing toward Brooklyn. By August 26, British scouts probed American outposts at Flatbush and Red Hook, sparking skirmishes. American riflemen under Col. Samuel Atlee engaged Hessian advance guards, losing ~50 men in brief clashes. Washington reinforced Brooklyn with 3,000 troops, expecting a frontal assault. Howe, however, planned a flanking maneuver via Jamaica Pass, setting up the main battle. August 26’s actions drew both armies into a fateful collision.

Forces and Battle Plans

4/ Washington’s 10,000 troops—half Continentals, half militia—held fortified lines from Gowanus Creek to Bedford. Key commanders: Israel Putnam, William Alexander (Lord Stirling). Howe’s 20,000 included British regulars, Hessian mercenaries, led by Henry Clinton and Charles Cornwallis. British plan: pin Americans with frontal feints while 10,000 under Clinton flanked via Jamaica Pass, a lightly guarded route. Washington, misreading British intent, concentrated forces at Brooklyn Heights, leaving the pass vulnerable. Heat and tension gripped the armies.

4/ Washington’s 10,000 troops—half Continentals, half militia—held fortified lines from Gowanus Creek to Bedford. Key commanders: Israel Putnam, William Alexander (Lord Stirling). Howe’s 20,000 included British regulars, Hessian mercenaries, led by Henry Clinton and Charles Cornwallis. British plan: pin Americans with frontal feints while 10,000 under Clinton flanked via Jamaica Pass, a lightly guarded route. Washington, misreading British intent, concentrated forces at Brooklyn Heights, leaving the pass vulnerable. Heat and tension gripped the armies.

The Battle Begins - British Flanking Maneuver

5/ At midnight August 26–27, Clinton’s 10,000 troops marched through Jamaica Pass, unguarded due to American scouting errors. By dawn August 27, they outflanked American lines at Bedford. British feints under Grant and Hessians under von Heister hit Gowanus and Flatbush, pinning Stirling and Sullivan’s divisions. At 8:00 AM, Clinton’s column struck from the rear, catching Americans off-guard. Cannon and musket volleys erupted; panic spread as patriots faced encirclement in Brooklyn’s fields and woods.

5/ At midnight August 26–27, Clinton’s 10,000 troops marched through Jamaica Pass, unguarded due to American scouting errors. By dawn August 27, they outflanked American lines at Bedford. British feints under Grant and Hessians under von Heister hit Gowanus and Flatbush, pinning Stirling and Sullivan’s divisions. At 8:00 AM, Clinton’s column struck from the rear, catching Americans off-guard. Cannon and musket volleys erupted; panic spread as patriots faced encirclement in Brooklyn’s fields and woods.

Fierce Fighting and American Collapse

6/ American defenses crumbled under the British flank attack. Sullivan’s 5,000 men at Battle Pass were routed, with 1,000 captured in chaotic retreats through woods. Stirling’s Marylanders held Gowanus Creek, fighting hand-to-hand against Grant’s regulars; 256 of 400 Marylanders fell, buying time. By noon, British forces converged, driving survivors to Brooklyn Heights. Militia fled; Continentals fought bravely but were overwhelmed. The battle’s intensity, with bayonets and smoke, marked a devastating American defeat.

6/ American defenses crumbled under the British flank attack. Sullivan’s 5,000 men at Battle Pass were routed, with 1,000 captured in chaotic retreats through woods. Stirling’s Marylanders held Gowanus Creek, fighting hand-to-hand against Grant’s regulars; 256 of 400 Marylanders fell, buying time. By noon, British forces converged, driving survivors to Brooklyn Heights. Militia fled; Continentals fought bravely but were overwhelmed. The battle’s intensity, with bayonets and smoke, marked a devastating American defeat.

Washington’s Retreat and Escape

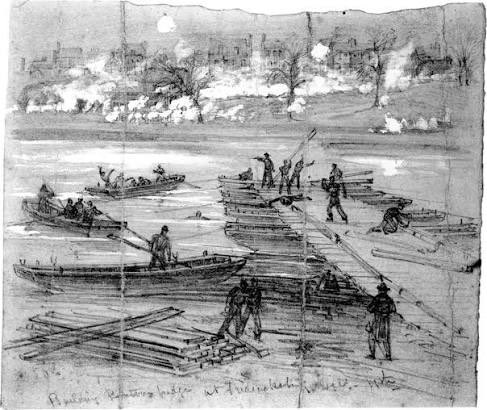

7/ By afternoon, ~9,000 Americans crowded Brooklyn Heights, expecting British assault. Howe, cautious after Bunker Hill, paused to siege. On August 29–30, under fog, Washington executed a daring retreat across the East River to Manhattan. 9,000 men, guns, and supplies evacuated silently in boats, undetected by British patrols. The retreat saved the army but ceded New York. British naval dominance loomed; Washington’s gamble preserved the Revolution’s core for future fights.

7/ By afternoon, ~9,000 Americans crowded Brooklyn Heights, expecting British assault. Howe, cautious after Bunker Hill, paused to siege. On August 29–30, under fog, Washington executed a daring retreat across the East River to Manhattan. 9,000 men, guns, and supplies evacuated silently in boats, undetected by British patrols. The retreat saved the army but ceded New York. British naval dominance loomed; Washington’s gamble preserved the Revolution’s core for future fights.

Casualties and Immediate Aftermath

8/ Long Island’s toll: ~2,400 casualties. Americans: ~300 dead, 700 wounded, 1,000 captured (including Sullivan). British/Hessians: ~63 dead, 314 wounded. Captured patriots faced brutal prison ships; many died in captivity. Howe occupied New York City, holding it until 1783. Washington regrouped in Manhattan, morale shaken but army intact. The defeat exposed militia weaknesses and command errors, prompting Washington to refine tactics. British overconfidence grew, setting up later setbacks.

8/ Long Island’s toll: ~2,400 casualties. Americans: ~300 dead, 700 wounded, 1,000 captured (including Sullivan). British/Hessians: ~63 dead, 314 wounded. Captured patriots faced brutal prison ships; many died in captivity. Howe occupied New York City, holding it until 1783. Washington regrouped in Manhattan, morale shaken but army intact. The defeat exposed militia weaknesses and command errors, prompting Washington to refine tactics. British overconfidence grew, setting up later setbacks.

Strategic Impact and Legacy

9/ Long Island’s loss handed Britain a strategic base, prolonging the war. It humiliated the Continental Army but taught Washington to avoid pitched battles against superior forces. The retreat became a masterstroke, preserving the Revolution. The battle spurred French interest, as American resolve persisted. Marylanders’ stand at Gowanus became legend, inspiring later victories. Long Island’s chaos, like your Camden thread’s rout, showed early war fragility but forged resilience for Yorktown.

9/ Long Island’s loss handed Britain a strategic base, prolonging the war. It humiliated the Continental Army but taught Washington to avoid pitched battles against superior forces. The retreat became a masterstroke, preserving the Revolution. The battle spurred French interest, as American resolve persisted. Marylanders’ stand at Gowanus became legend, inspiring later victories. Long Island’s chaos, like your Camden thread’s rout, showed early war fragility but forged resilience for Yorktown.

Conclusion of the Battle of Long Island

10/ The Battle of Long Island, sparked by skirmishes on August 26, 1776, was a crushing American defeat, costing ~2,400 casualties and New York City. Howe’s flanking brilliance overwhelmed Washington’s forces, yet his retreat saved the Revolution. Amid Brooklyn’s fields, the battle tested a fledgling nation, exposing flaws but steeling resolve. Like Camden or Wilson’s Creek, it was a bitter setback that fueled perseverance, shaping the path to independence through sacrifice and survival.

10/ The Battle of Long Island, sparked by skirmishes on August 26, 1776, was a crushing American defeat, costing ~2,400 casualties and New York City. Howe’s flanking brilliance overwhelmed Washington’s forces, yet his retreat saved the Revolution. Amid Brooklyn’s fields, the battle tested a fledgling nation, exposing flaws but steeling resolve. Like Camden or Wilson’s Creek, it was a bitter setback that fueled perseverance, shaping the path to independence through sacrifice and survival.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh