There are only two possible theories for life’s origin: blind chance or intentional design.

The problem for naturalists is that the more we learn about life, the more impossible their theory becomes.

But just how unlikely is it?

Here’s why life is 100% designed🧵

The problem for naturalists is that the more we learn about life, the more impossible their theory becomes.

But just how unlikely is it?

Here’s why life is 100% designed🧵

How Simple Can a Cell Be?

To determine how unlikely life is to arise without a mind, we must first ask “how simple can a cell be and still survive?”

In 2016, scientists at the J. Craig Venter Institute created JCVI-syn3.0, the simplest self-replicating cell ever made. They stripped away every gene that wasn’t absolutely necessary for survival.

Here’s what they found:

•The cell still needed 473 genes in total.

•438 of those genes coded for 438 distinct, functional proteins, each one a precision molecular engine built from amino acids.

•Every one of those proteins was essential for the cell to live, metabolize, and reproduce. Remove any of them, and the cell would die.

From this study we can safely say that 400 distinct functional proteins is the bare minimum for life.

So how easy is it to get these proteins?

To determine how unlikely life is to arise without a mind, we must first ask “how simple can a cell be and still survive?”

In 2016, scientists at the J. Craig Venter Institute created JCVI-syn3.0, the simplest self-replicating cell ever made. They stripped away every gene that wasn’t absolutely necessary for survival.

Here’s what they found:

•The cell still needed 473 genes in total.

•438 of those genes coded for 438 distinct, functional proteins, each one a precision molecular engine built from amino acids.

•Every one of those proteins was essential for the cell to live, metabolize, and reproduce. Remove any of them, and the cell would die.

From this study we can safely say that 400 distinct functional proteins is the bare minimum for life.

So how easy is it to get these proteins?

Not easy at all.

Proteins are chains of amino acids that must fold into precise 3D shapes to work. If the fold is wrong, then the amino acids fall apart and the protein is useless.

Studies show that the odds of getting a single functional protein fold from random amino acids are about 1 in 10⁷⁷ (Axe, Journal of Molecular Biology, 2004).

To help you understand how large this number is, the number of particles in our observable universe is about 10^80.

That means the odds of mindlessly assembling just one functional protein is almost as small as the odds of a blind man picking out the one marked atom from the entire observable universe.

Proteins are chains of amino acids that must fold into precise 3D shapes to work. If the fold is wrong, then the amino acids fall apart and the protein is useless.

Studies show that the odds of getting a single functional protein fold from random amino acids are about 1 in 10⁷⁷ (Axe, Journal of Molecular Biology, 2004).

To help you understand how large this number is, the number of particles in our observable universe is about 10^80.

That means the odds of mindlessly assembling just one functional protein is almost as small as the odds of a blind man picking out the one marked atom from the entire observable universe.

But it’s even worse than that, because we don’t just need one protein… we need at least 400.

And it’s even worse than that, because just finding a protein isn’t enough, it has to be a protein that has the correct function for that cell, otherwise it’s junk or it can even damage the system.

If the odds of finding even one functional protein are 1 in 10^77, what do you think the odds are of mindlessly finding 400 correct functional proteins all at the same time and in the same place?

But it’s even worse than that.

And it’s even worse than that, because just finding a protein isn’t enough, it has to be a protein that has the correct function for that cell, otherwise it’s junk or it can even damage the system.

If the odds of finding even one functional protein are 1 in 10^77, what do you think the odds are of mindlessly finding 400 correct functional proteins all at the same time and in the same place?

But it’s even worse than that.

Even if you have 400 proteins that all happened to fold together in the exact right ways to allow the cell to function… you still need DNA to make more of these proteins.

Before we talk about the information stored in DNA, just getting the raw molecule “DNA” to form on its own—in nature and with no help—is basically impossible. This is because DNA is made of special building blocks called nucleotides, and they have to link up in exactly the right way, like snapping together thousands of Lego pieces without a guide, instructions, or even a flat surface.

These building blocks don’t naturally form in the right shape and the pieces have to line up perfectly, all in the same “handedness,” or it falls apart.

So how likely is it for the DNA molecule to form naturally?

Imagine you dumped out a box of puzzle pieces—not just one puzzle, but 500,000 pieces from 10,000 puzzles all mixed together. Then you waited for the wind to blow them all correctly into place. That’s about how likely it is for a single strand of DNA to form by chance.

And this is JUST to get the DNA to form correctly.

Before we talk about the information stored in DNA, just getting the raw molecule “DNA” to form on its own—in nature and with no help—is basically impossible. This is because DNA is made of special building blocks called nucleotides, and they have to link up in exactly the right way, like snapping together thousands of Lego pieces without a guide, instructions, or even a flat surface.

These building blocks don’t naturally form in the right shape and the pieces have to line up perfectly, all in the same “handedness,” or it falls apart.

So how likely is it for the DNA molecule to form naturally?

Imagine you dumped out a box of puzzle pieces—not just one puzzle, but 500,000 pieces from 10,000 puzzles all mixed together. Then you waited for the wind to blow them all correctly into place. That’s about how likely it is for a single strand of DNA to form by chance.

And this is JUST to get the DNA to form correctly.

But we don’t JUST need the DNA to form… we also need it to be correctly sequenced so it can create more proteins. Without DNA correctly sequenced, the already existing 400 proteins can’t be renewed or replicated and the cell will die.

The sequence of bases in DNA (A, T, C, G) must be arranged just right to code for functional proteins.

If even a single codon (3-base sequence) is incorrect in the wrong place, it can render the resulting protein nonfunctional or even toxic. This means only a tiny fraction of all possible DNA sequences will produce anything remotely useful.

Imagine tossing half a million Scrabble tiles out of an airplane and expecting them to land on the ground spelling the entire instruction manual for a self-replicating robot. No typos, all the grammar correct, and every page in order… it’s like that.

But it’s still even worse…

The sequence of bases in DNA (A, T, C, G) must be arranged just right to code for functional proteins.

If even a single codon (3-base sequence) is incorrect in the wrong place, it can render the resulting protein nonfunctional or even toxic. This means only a tiny fraction of all possible DNA sequences will produce anything remotely useful.

Imagine tossing half a million Scrabble tiles out of an airplane and expecting them to land on the ground spelling the entire instruction manual for a self-replicating robot. No typos, all the grammar correct, and every page in order… it’s like that.

But it’s still even worse…

In order to make proteins, you need DNA, but in order to use the DNA to make the proteins… you need dozens of already existing proteins.

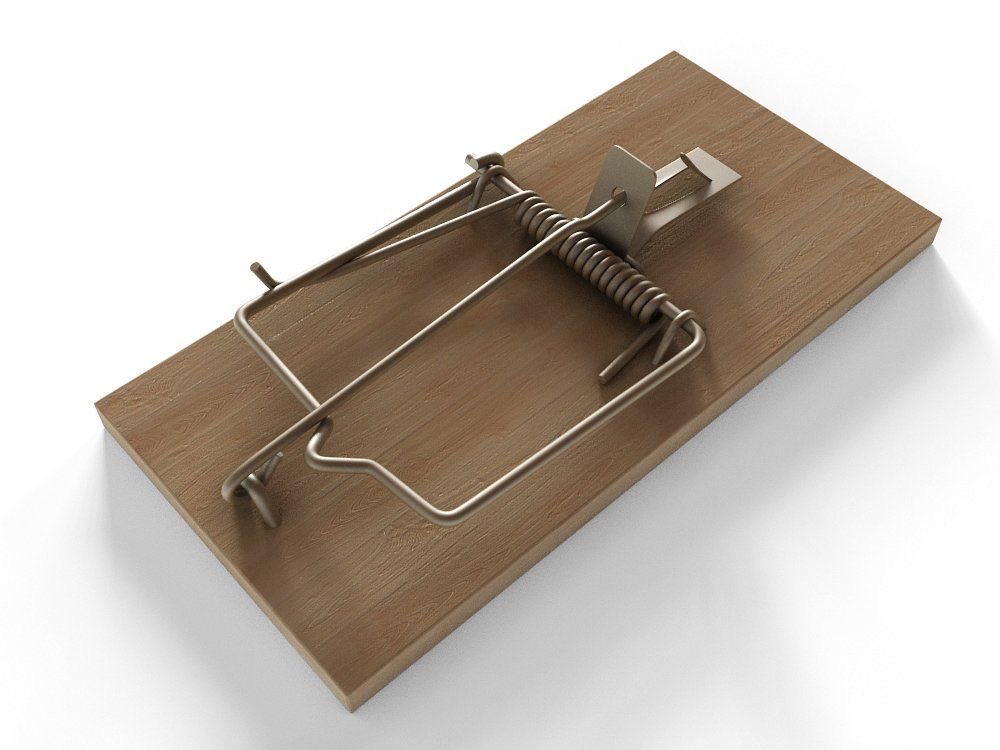

This means—like a mouse trap—life is irreducibly complex. You need proteins and DNA to both form correctly, in the same place and at the same time, independently… the chances of this happening without a mind are unfathomably remote.

And it’s even worse than this…

This means—like a mouse trap—life is irreducibly complex. You need proteins and DNA to both form correctly, in the same place and at the same time, independently… the chances of this happening without a mind are unfathomably remote.

And it’s even worse than this…

You also need this to happen within a cell membrane.

Even if you had all the pieces of life, like DNA and proteins, they would be completely useless without something to hold them together and protect them. That “something” is called a cell membrane.

A cell membrane is like the skin of a water balloon. It keeps all the important stuff inside and keeps the bad stuff out. Without it, everything would just float away or fall apart.

But here’s the problem: making a working membrane without help is really hard. The special fats that make it are complex and don’t form easily in nature. And real membranes also need tiny machines built into them to let food in and waste out. Those machines are proteins. But remember, proteins can’t be made unless you already have DNA and other proteins working together inside the membrane.

So you need the membrane to hold the proteins and DNA, but you also need the proteins and DNA to make the membrane. It’s like needing the lid of a jar to store the pieces that make the lid. It doesn’t work unless it’s all there at once.

This video explains how difficult it is to make a cell membrane

Even if you had all the pieces of life, like DNA and proteins, they would be completely useless without something to hold them together and protect them. That “something” is called a cell membrane.

A cell membrane is like the skin of a water balloon. It keeps all the important stuff inside and keeps the bad stuff out. Without it, everything would just float away or fall apart.

But here’s the problem: making a working membrane without help is really hard. The special fats that make it are complex and don’t form easily in nature. And real membranes also need tiny machines built into them to let food in and waste out. Those machines are proteins. But remember, proteins can’t be made unless you already have DNA and other proteins working together inside the membrane.

So you need the membrane to hold the proteins and DNA, but you also need the proteins and DNA to make the membrane. It’s like needing the lid of a jar to store the pieces that make the lid. It doesn’t work unless it’s all there at once.

This video explains how difficult it is to make a cell membrane

This is why evolutionists (people that claim life is not the product of design) are now arguing that evolution and abiogenesis are two completely different and unrelated theories… because the more we learn about life the more impossible their naturalist theory becomes.

So, if the odds that life is the product of mindless unintentional processes are functionally 0%, how likely is it that life is the product of an intelligent, intentional cause?

100%

So, if the odds that life is the product of mindless unintentional processes are functionally 0%, how likely is it that life is the product of an intelligent, intentional cause?

100%

The case against naturalism is overwhelmingly strong.

If you want to help more people see why, please retweet this thread

If you want to help more people see why, please retweet this thread

https://twitter.com/darwintojesus/status/1961087688913654052

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh