Civilizations don’t begin with kings or armies — they begin with stories.

The Epic of Gilgamesh, Homer’s Iliad, Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings — separated by thousands of years, they’re all asking the same question:

How do you turn chaos into meaning? 🧵

The Epic of Gilgamesh, Homer’s Iliad, Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings — separated by thousands of years, they’re all asking the same question:

How do you turn chaos into meaning? 🧵

The oldest epic we know is about Gilgamesh, king of Uruk, who lost his closest friend and went searching for immortality, only to learn that no man escapes death.

He learned that meaning lies in what we build and leave behind.

Across time, stories help us face death and make sense of a broken world.

He learned that meaning lies in what we build and leave behind.

Across time, stories help us face death and make sense of a broken world.

That was 4,000 years ago. But the pattern never changed.

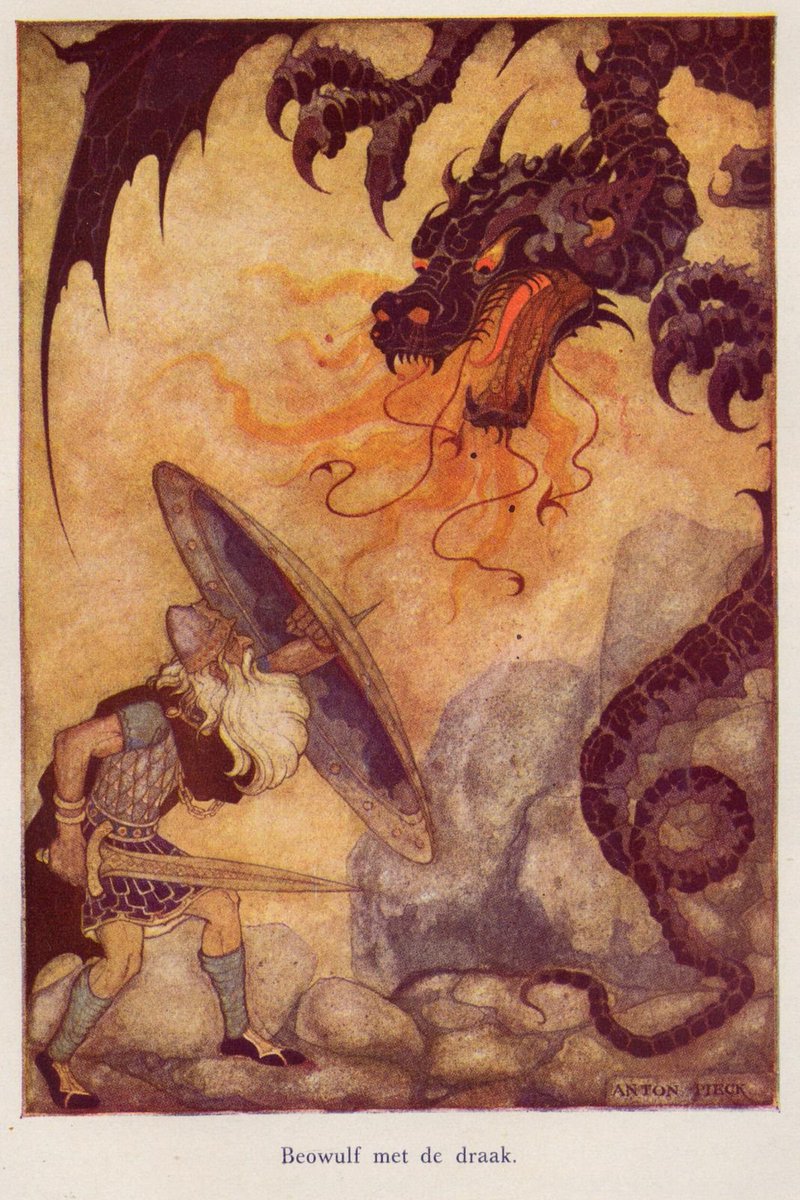

Every epic since has wrestled with the same truth: chaos comes for all of us.

And every culture turned to stories to tame it.

Every epic since has wrestled with the same truth: chaos comes for all of us.

And every culture turned to stories to tame it.

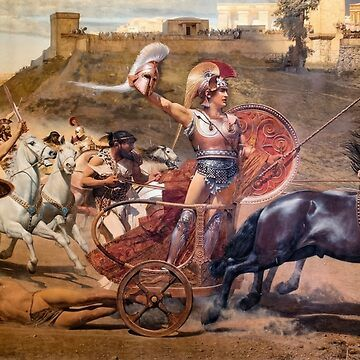

Homer faced the chaos of war.

In the Iliad, rage tears heroes and cities apart. But it wasn’t just about war.

It was about what makes honor worth dying for. The chaos of battle became a meditation on glory, loss, and memory.

That’s how the Greeks made sense of destruction.

In the Iliad, rage tears heroes and cities apart. But it wasn’t just about war.

It was about what makes honor worth dying for. The chaos of battle became a meditation on glory, loss, and memory.

That’s how the Greeks made sense of destruction.

The Odyssey took it further.

It’s not really about monsters and sea voyages.

It’s about whether home and belonging can ever be reclaimed after chaos tears it away.

It’s not really about monsters and sea voyages.

It’s about whether home and belonging can ever be reclaimed after chaos tears it away.

Rome needed something else.

So, Virgil wrote the Aeneid: grief transformed into a founding myth.

It taught that even destruction can be turned into destiny.

So, Virgil wrote the Aeneid: grief transformed into a founding myth.

It taught that even destruction can be turned into destiny.

Shakespeare inherited myth’s grandeur and shrank it into a human skull.

Hamlet’s conscience was as epic as Achilles’ rage. Romeo and Juliet’s love felt as fated as Troy’s fall.

Chaos wasn’t out there anymore. It was inside us.

Hamlet’s conscience was as epic as Achilles’ rage. Romeo and Juliet’s love felt as fated as Troy’s fall.

Chaos wasn’t out there anymore. It was inside us.

For the first time, the battlefield wasn’t Troy or Rome.

It was the mind itself.

And Shakespeare showed that our inner storms needed stories just as much as wars ever did.

It was the mind itself.

And Shakespeare showed that our inner storms needed stories just as much as wars ever did.

Then came the novel.

Defoe marooned a man on an island.

Richardson gave voice to a servant girl.

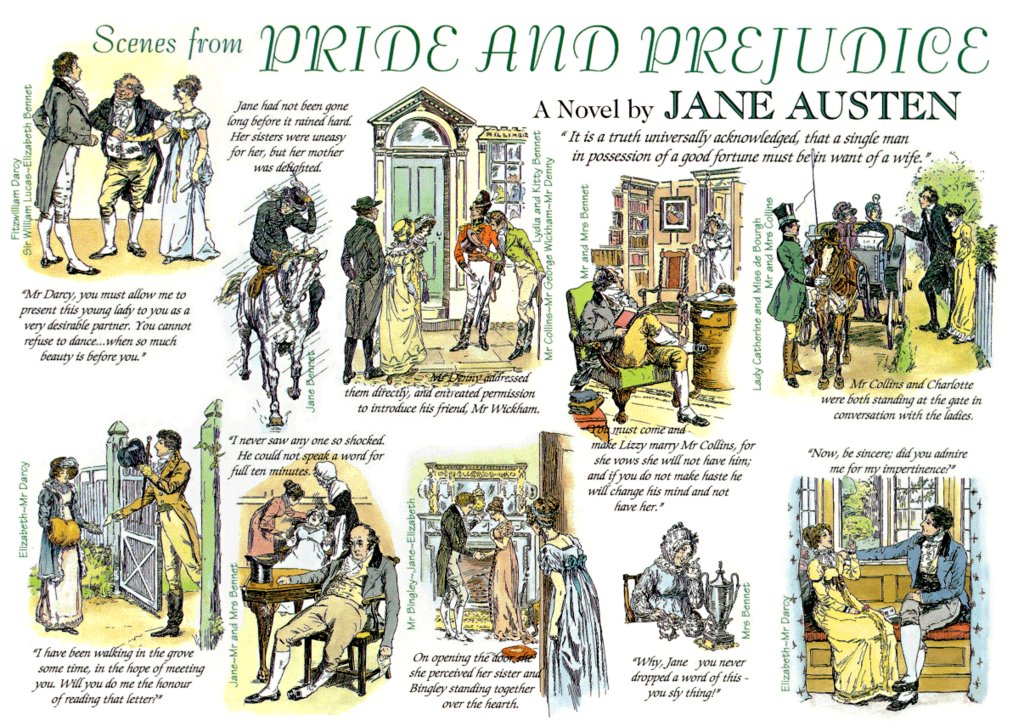

Austen turned marriage into comedy and war of manners.

The novel was proof that ordinary lives could be as meaningful as heroes.

Defoe marooned a man on an island.

Richardson gave voice to a servant girl.

Austen turned marriage into comedy and war of manners.

The novel was proof that ordinary lives could be as meaningful as heroes.

Empathy didn’t come from politics.

It came from novels, training entire societies to see through the eyes of strangers.

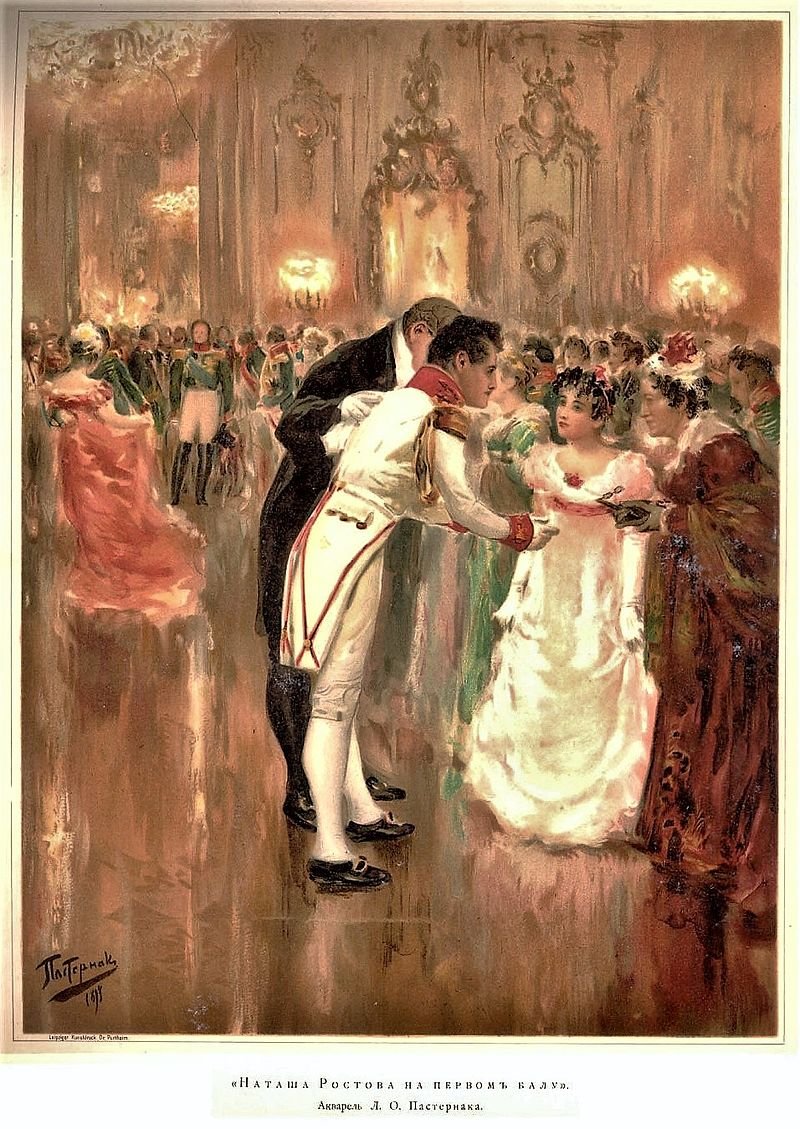

That’s why Dickens mattered as much as any reformer. Why Tolstoy mattered as much as any general.

It came from novels, training entire societies to see through the eyes of strangers.

That’s why Dickens mattered as much as any reformer. Why Tolstoy mattered as much as any general.

The 20th century brought two world wars. Old, tidy storytelling felt fake.

So, writers changed how they wrote:

Joyce turned one day in Dublin into an epic of wandering thoughts;

Woolf let us live inside a mind as it moved from one thought to the next;

Eliot used a collage of voices to match a broken time.

All three were saying the same thing: the world was in pieces, but you can still make meaning from the pieces.

So, writers changed how they wrote:

Joyce turned one day in Dublin into an epic of wandering thoughts;

Woolf let us live inside a mind as it moved from one thought to the next;

Eliot used a collage of voices to match a broken time.

All three were saying the same thing: the world was in pieces, but you can still make meaning from the pieces.

But not every writer fractured. Some warned.

Orwell didn’t just write books.

He wrote warning flares for civilization.

1984 and Animal Farm are still our immune system against tyranny. Ignore them, and the disease returns.

Orwell didn’t just write books.

He wrote warning flares for civilization.

1984 and Animal Farm are still our immune system against tyranny. Ignore them, and the disease returns.

And some rebuilt.

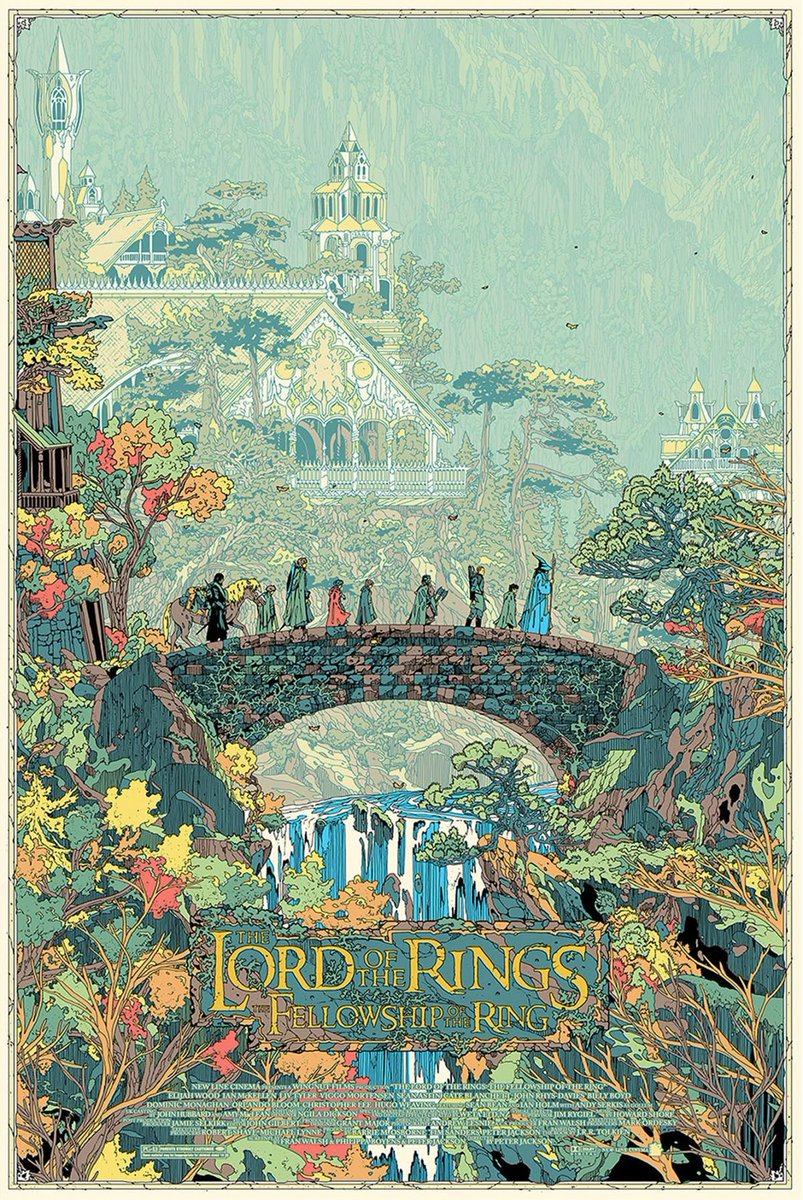

Tolkien forged a new epic from the ashes of war.

Tolkien rebuilt the epic, not to escape reality, but to heal it.

When modernism showed us despair, he showed us fellowship and hope.

Tolkien forged a new epic from the ashes of war.

Tolkien rebuilt the epic, not to escape reality, but to heal it.

When modernism showed us despair, he showed us fellowship and hope.

When empires collapsed, writers from Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean picked up the pen.

Achebe showed Africa’s side of the story in Things Fall Apart. Walcott rewrote Homer with Caribbean voices. Rushdie told India’s history through magical births.

This was literature being used to reclaim the narrative.

Achebe showed Africa’s side of the story in Things Fall Apart. Walcott rewrote Homer with Caribbean voices. Rushdie told India’s history through magical births.

This was literature being used to reclaim the narrative.

Then Latin America gave another answer: magical realism.

Márquez filled a village with ghosts and endless rain. Borges wrote about infinite books and impossible mazes.

The chaos was a world where reality felt unbelievable. The meaning was to show that myth and memory are part of everyday life.

Márquez filled a village with ghosts and endless rain. Borges wrote about infinite books and impossible mazes.

The chaos was a world where reality felt unbelievable. The meaning was to show that myth and memory are part of everyday life.

So, from Gilgamesh to Márquez, the same pattern holds.

Every reinvention of literature is civilization facing its crisis and asking:

How do we turn this chaos into meaning?

Every reinvention of literature is civilization facing its crisis and asking:

How do we turn this chaos into meaning?

The forms change: epic, drama, novel, modernism, magical realism.

But the heartbeat is the same: each age tells stories not to escape chaos, but to endure it.

But the heartbeat is the same: each age tells stories not to escape chaos, but to endure it.

So, what does all this mean?

Civilizations collapse when they forget their stories.

But they endure when they remember because stories are the immune system of culture.

Civilizations collapse when they forget their stories.

But they endure when they remember because stories are the immune system of culture.

Armies crumble. Cities burn. Empires vanish.

But Homer still sings.

Dante still guides.

Shakespeare still stages.

Orwell still warns.

Achebe still restores.

The pen doesn’t just beat the sword, it outlives it.

But Homer still sings.

Dante still guides.

Shakespeare still stages.

Orwell still warns.

Achebe still restores.

The pen doesn’t just beat the sword, it outlives it.

This thread came from my newsletter article, "Literature Is Our Immune System".

If you believe stories are the only true defense civilizations have, you’ll want to read the full piece.

newsletter.thecultureexplorer.com/subscribe

If you believe stories are the only true defense civilizations have, you’ll want to read the full piece.

newsletter.thecultureexplorer.com/subscribe

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh