Friend @cirsova is surely too modest here, as he is also no slouch at doing thematic and structural analysis.

But why don't we talk about criticism? I do this as a hobby, and I can't cover everything. More critics would be a good thing.

But why don't we talk about criticism? I do this as a hobby, and I can't cover everything. More critics would be a good thing.

https://x.com/cirsova/status/1965210710126080056

The function of a critic is something I only gradually understood.

I borrow my understand of criticism in part from Susan Rogers "This is What it Sounds Like".

I borrow my understand of criticism in part from Susan Rogers "This is What it Sounds Like".

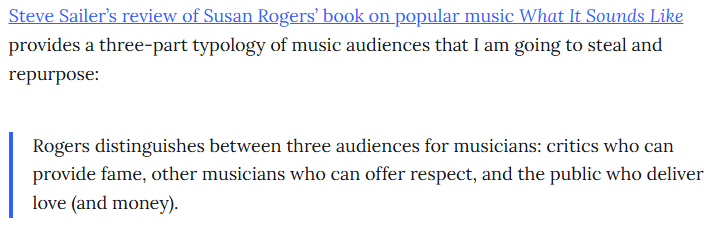

Thanks to @Steve_Sailer, I see the function of a literary critic as analogous to how Rogers describes music critics.

Critics assess whether an author has done a difficult job well, or contributed to the Great Conversation in a lasting way.

Other writers assess an author’s craft as a writer, peer-to-peer.

The public buys books and writes an author fan mail.

Other writers assess an author’s craft as a writer, peer-to-peer.

The public buys books and writes an author fan mail.

One of the key functions I serve is that I'm *not* an author of fiction.

Lots of conversations about books, especially in the doomed #WritingCommunity are authors talking to each other.

Lots of conversations about books, especially in the doomed #WritingCommunity are authors talking to each other.

Discussions about author craft have their place, but criticism is something different. It is a different skill set and a different point of view.

Another important thing that I do is work to gain trust. I actively engage at my website and here with authors because I wish to maintain good relations.

https://x.com/CatalyticComics/status/1965253544950567137

But at the same time I need to maintain my independence.

One time I can remember having the thought: "if I say this will I keep getting review copies?"

And I realized that was potential bias. I have to be willing to be an asshole sometimes.

One time I can remember having the thought: "if I say this will I keep getting review copies?"

And I realized that was potential bias. I have to be willing to be an asshole sometimes.

It is important that what I say about stories be as honest as possible, so while I do accept review copies, I also make sure to go buy books for the purpose of criticism as well.

I also try to be fair in what I say.

I also try to be fair in what I say.

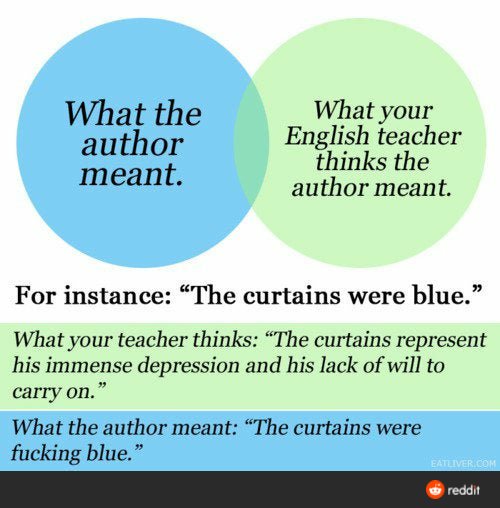

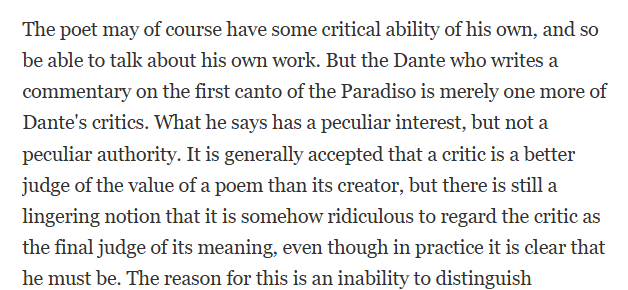

This is especially important because taste =/= criticism.

Whether I like a book, or a genre, or even an author needs to take a back seat.

Whether I like a book, or a genre, or even an author needs to take a back seat.

This is genuinely hard. But I think an example of how this works is by engaging with authors who contribute to the Great Conversation, authors who influence other authors and help define genres.

https://x.com/BenEspen/status/1859697277918748958

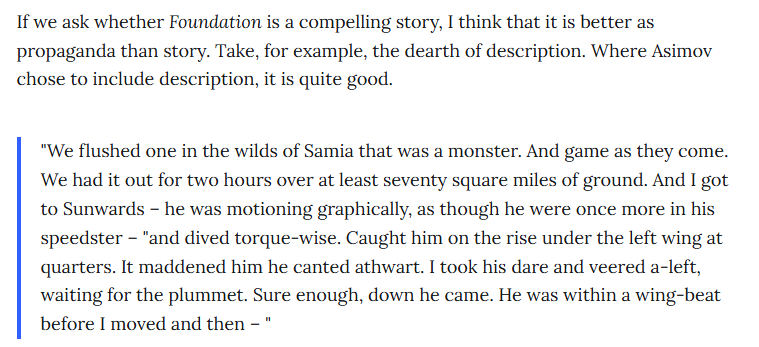

But also by being honest when a famous story isn't a good story. A lot of 19th & 20th c. literature is really disguised discursive writing, where plot and characterization is secondary to theme.

But this sells short the true power of stories, which operate at a different level of abstraction than discursive writing.

Stories are hypothetically related to our world, and their power comes from being able to succinctly communicate the possible.

Stories are hypothetically related to our world, and their power comes from being able to succinctly communicate the possible.

https://x.com/BenEspen/status/1817917793326797157

I invite anyone with an interest in this to pick up the crown lying in the gutter. Criticism is too important to ignore.

/END

/END

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh