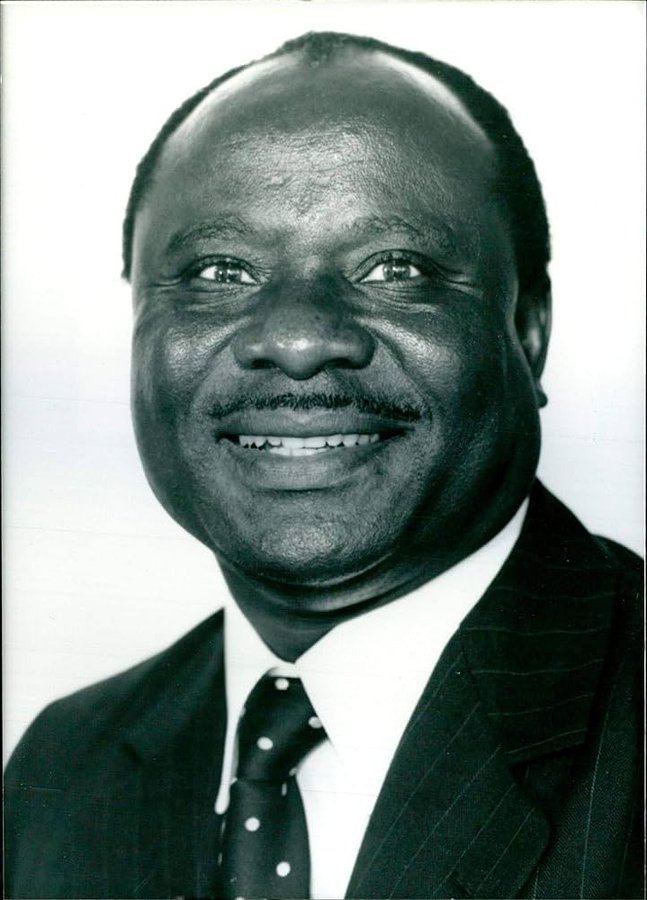

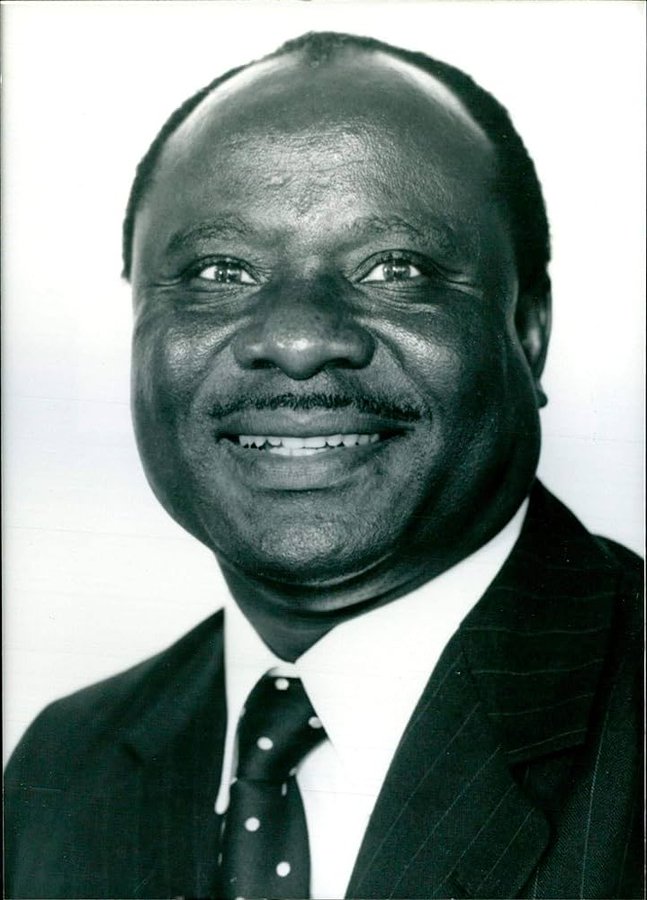

🧵 Oliver Mtukudzi: The Voice That Betrayed Zimbabwe

1/

22 September 1952.

Highfield, Salisbury.

A cry cuts through the township.

Harsh.

Rasping.

Unforgettable.

Outside, vadzimu roam the air.

Police trucks patrol.

Overcrowded houses sweat in the heat — paraffin lamps flicker against cracked walls.

Beer foams in shebeens.

Street football scatters dust into the twilight.

Oliver Mtukudzi is born.

1/

22 September 1952.

Highfield, Salisbury.

A cry cuts through the township.

Harsh.

Rasping.

Unforgettable.

Outside, vadzimu roam the air.

Police trucks patrol.

Overcrowded houses sweat in the heat — paraffin lamps flicker against cracked walls.

Beer foams in shebeens.

Street football scatters dust into the twilight.

Oliver Mtukudzi is born.

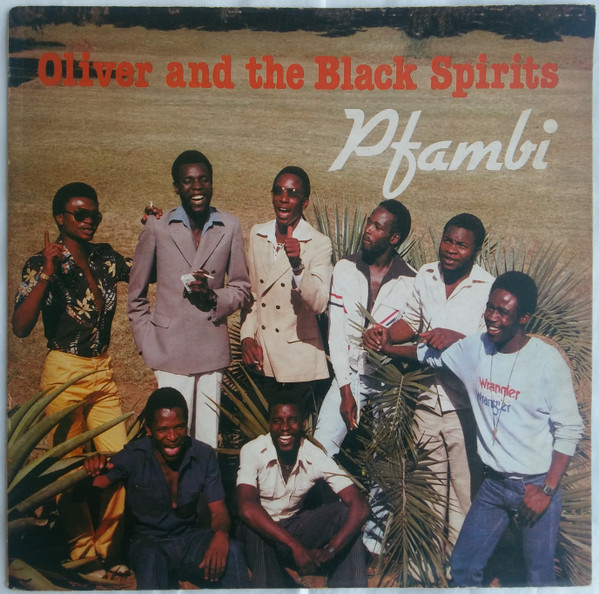

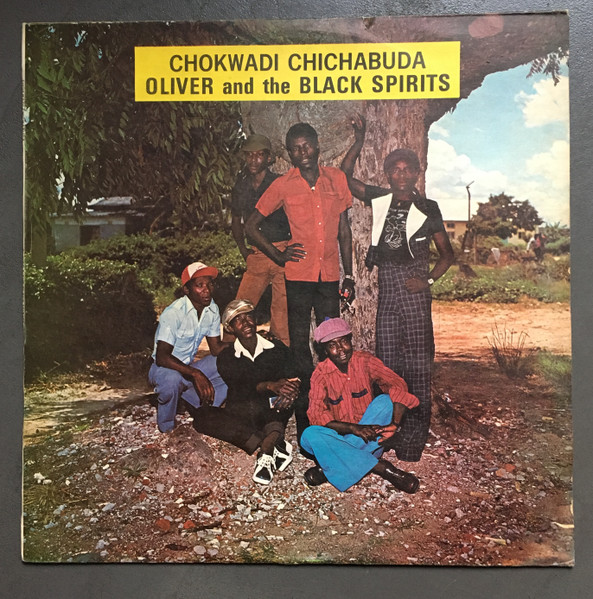

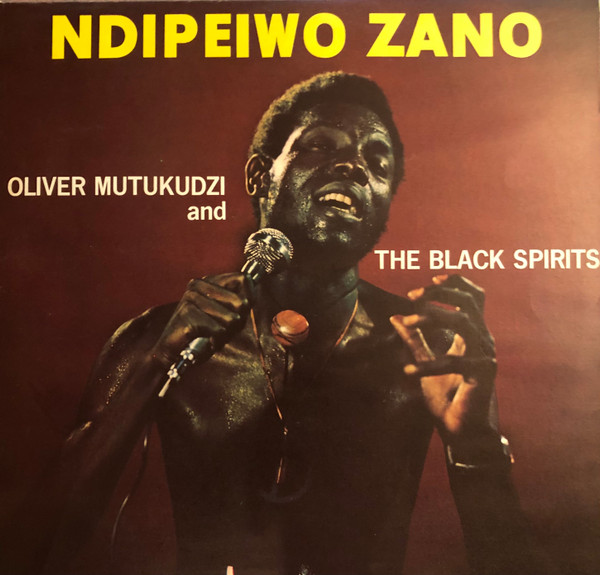

2/

25 years later.

1977.

Highfield hums.

Guitars shimmer in crowded bars.

Horns pierce the cigarette smoke.

Drums crack like gunfire in the night.

The Black Spirits form.

Dzandimomotera bursts across the township.

Highfield crowns its griot — tall, black, and husky.

Zimbabwe remains chained.

But freedom vibrates in Mtukudzi’s chords.

25 years later.

1977.

Highfield hums.

Guitars shimmer in crowded bars.

Horns pierce the cigarette smoke.

Drums crack like gunfire in the night.

The Black Spirits form.

Dzandimomotera bursts across the township.

Highfield crowns its griot — tall, black, and husky.

Zimbabwe remains chained.

But freedom vibrates in Mtukudzi’s chords.

3/

Independence.

April 1980.

Soldiers return — men and women hardened by war.

Boys and girls stream back from Zambia and Mozambique.

Exiles pour home with hope in their eyes.

A fractured nation collides in celebration.

Mtukudzi becomes their mirror.

Jeri — a lament for a fallen friend.

Rufu Ndimadzongonyedze — where love reigns, death is a heartless disruptor.

Seiko — a metaphorical plea to God, asking why suffering stalks the innocent.

Tuku’s voice becomes the country’s cry.

Independence.

April 1980.

Soldiers return — men and women hardened by war.

Boys and girls stream back from Zambia and Mozambique.

Exiles pour home with hope in their eyes.

A fractured nation collides in celebration.

Mtukudzi becomes their mirror.

Jeri — a lament for a fallen friend.

Rufu Ndimadzongonyedze — where love reigns, death is a heartless disruptor.

Seiko — a metaphorical plea to God, asking why suffering stalks the innocent.

Tuku’s voice becomes the country’s cry.

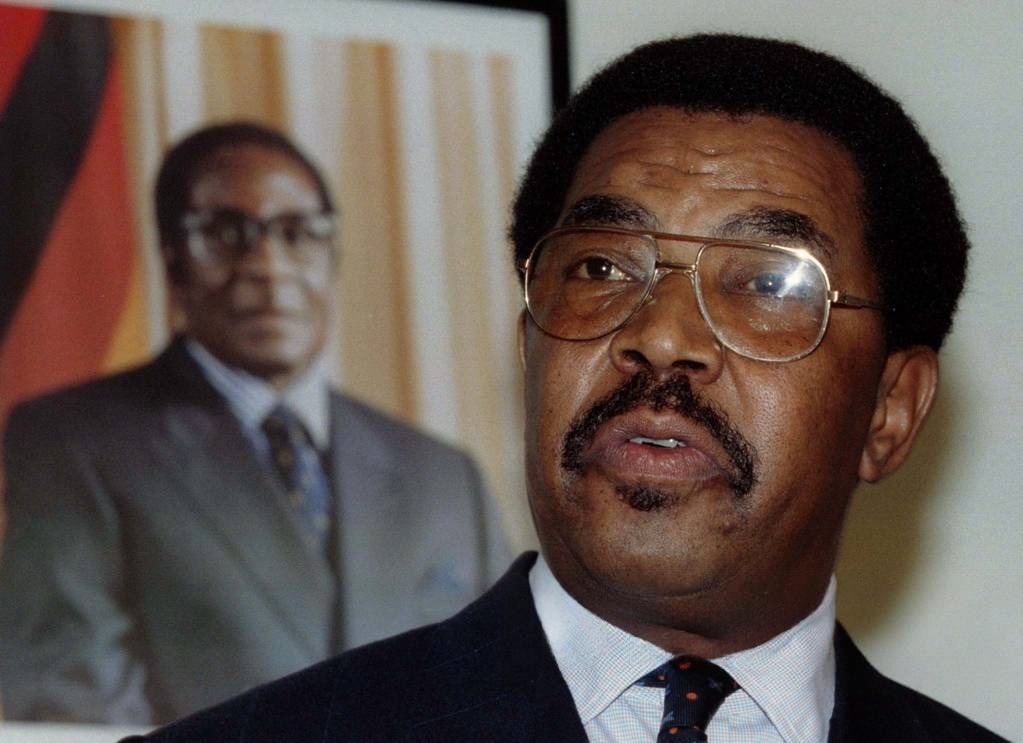

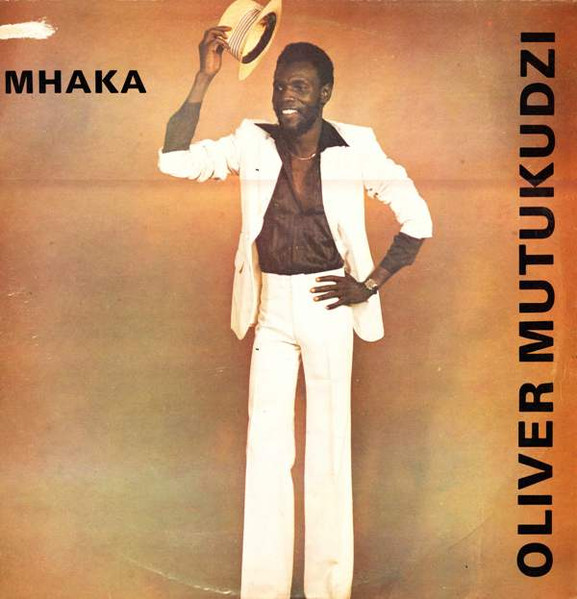

4/

The 1990s.

His voice dims on the airwaves.

Sungura kings rule the dancefloors — basslines thundering through rural nights.

Tuku chases a hit.

A comeback.

A new beginning.

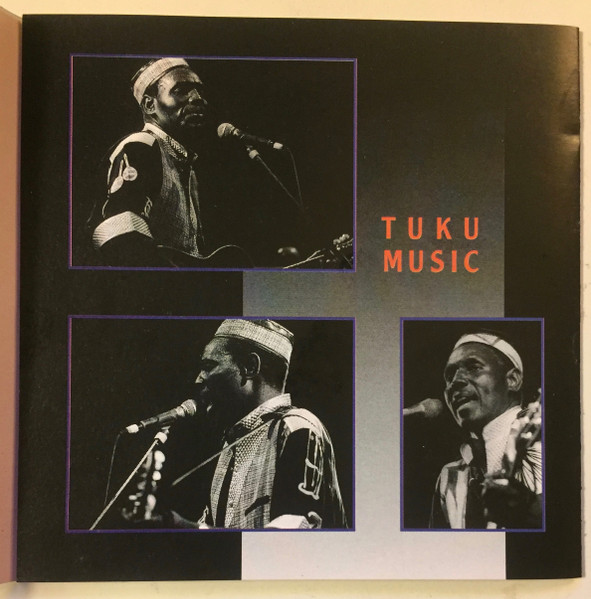

Tuku Music in 1998.

Dzoka Uyamwe.

Tsika Dzedu.

Mai Varamba.

Todii.

The world stops to hail a maestro.

Africa crowns him — a towering performer, loved across the continent and admired around the world.

The 1990s.

His voice dims on the airwaves.

Sungura kings rule the dancefloors — basslines thundering through rural nights.

Tuku chases a hit.

A comeback.

A new beginning.

Tuku Music in 1998.

Dzoka Uyamwe.

Tsika Dzedu.

Mai Varamba.

Todii.

The world stops to hail a maestro.

Africa crowns him — a towering performer, loved across the continent and admired around the world.

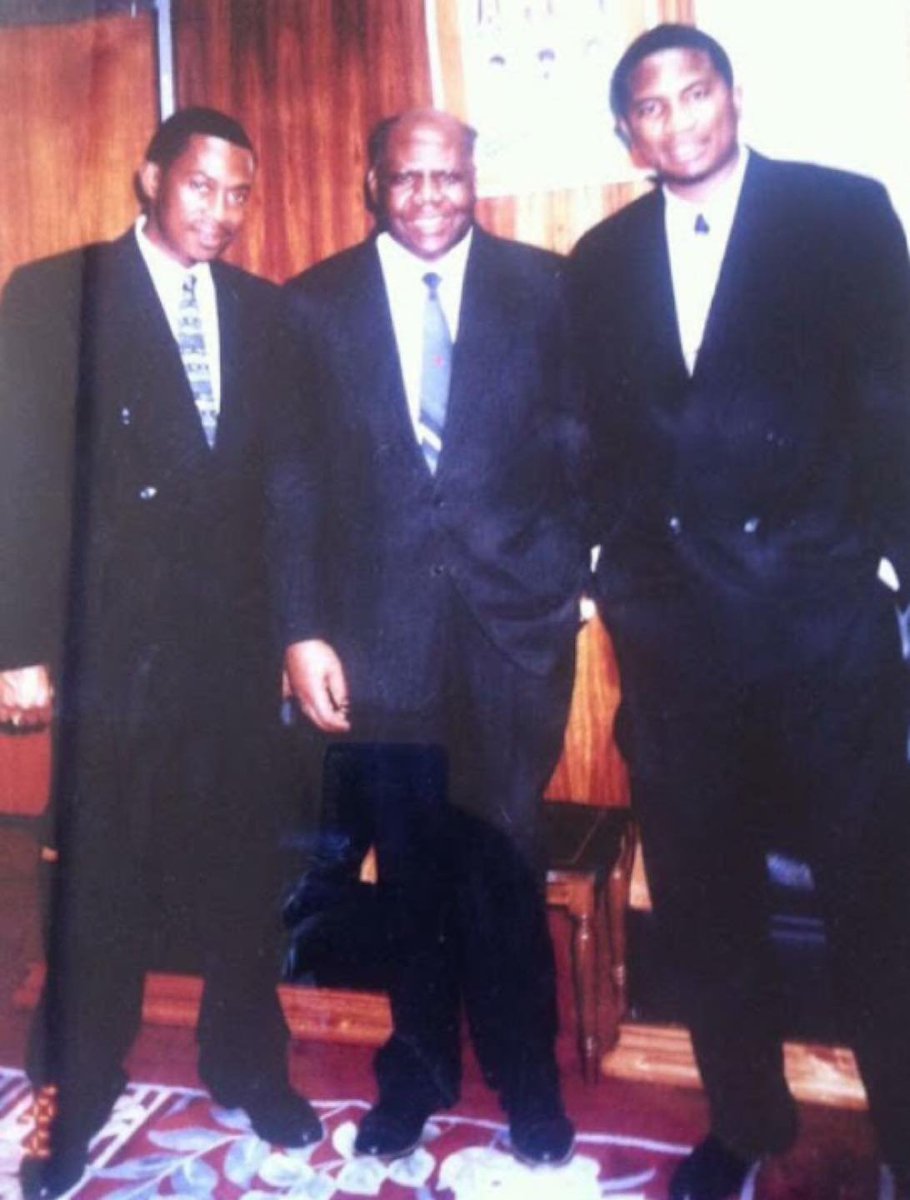

5/

The resurgence reshapes him.

He is no longer just Highfield’s griot.

He becomes Zimbabwe’s conscience in song.

Mkuru Mkuru.

A parable on leadership — elders must lead by example, and accept criticism when they go wrong.

Pindurai Mambo.

A cry for the Lord to answer as people stagger through hardship.

Mutserendende.

He recalls the easier, abundant days of his ancestors, as his generation climbs mountains.

He urges perseverance — the plain awaits beyond the summit.

Even in struggle, he celebrates life.

Crowds sway to his return.

The old rasp cuts new wounds.

A moral voice rises.

The resurgence reshapes him.

He is no longer just Highfield’s griot.

He becomes Zimbabwe’s conscience in song.

Mkuru Mkuru.

A parable on leadership — elders must lead by example, and accept criticism when they go wrong.

Pindurai Mambo.

A cry for the Lord to answer as people stagger through hardship.

Mutserendende.

He recalls the easier, abundant days of his ancestors, as his generation climbs mountains.

He urges perseverance — the plain awaits beyond the summit.

Even in struggle, he celebrates life.

Crowds sway to his return.

The old rasp cuts new wounds.

A moral voice rises.

6/

But myths cast shadows.

At home, the moral voice crumbles.

Sandra recalls cruelty — forced to share sadza with the family dog, left behind in an empty house she didn’t know they’d moved from.

Selmor recalls neglect — excluded from holidays, treated as an outcast, overlooked until the world was watching.

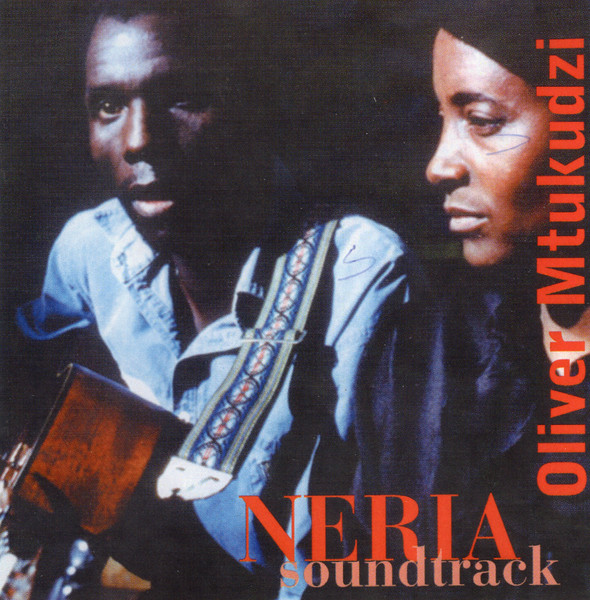

The man who sings for widows in Neria.

Who pleads in Mai Varamba — urging an overprotective mother to let her son go and find his path.

Who warns in Tozeza Baba — a haunting tale of a drunkard father who beats his wife and rules his home through fear.

He becomes the man who breaks his own daughters.

A father in public.

A tyrant at home.

A heartless ghost to his own child.

But myths cast shadows.

At home, the moral voice crumbles.

Sandra recalls cruelty — forced to share sadza with the family dog, left behind in an empty house she didn’t know they’d moved from.

Selmor recalls neglect — excluded from holidays, treated as an outcast, overlooked until the world was watching.

The man who sings for widows in Neria.

Who pleads in Mai Varamba — urging an overprotective mother to let her son go and find his path.

Who warns in Tozeza Baba — a haunting tale of a drunkard father who beats his wife and rules his home through fear.

He becomes the man who breaks his own daughters.

A father in public.

A tyrant at home.

A heartless ghost to his own child.

7/

On screen in Neria, he protects a grieving widow.

Shields her dignity with song.

Off screen, his daughters learn to endure.

Neglect shadows Selmor’s path.

Viciousness lingers in Sandra’s steps.

The protector on screen.

The destroyer of spirit at home.

On screen in Neria, he protects a grieving widow.

Shields her dignity with song.

Off screen, his daughters learn to endure.

Neglect shadows Selmor’s path.

Viciousness lingers in Sandra’s steps.

The protector on screen.

The destroyer of spirit at home.

8/

He sings Dzoka Uyamwe.

A metaphorical return — a mother beckoning her son home, an ancestral pull toward belonging.

But his own daughters grow up estranged.

Sandra moves through echoes of brutality.

Selmor meanders through the shadows of neglect.

The embrace he sang about never reached them.

A voice that promised care, awareness, pride.

A man that delivered none.

He sings Dzoka Uyamwe.

A metaphorical return — a mother beckoning her son home, an ancestral pull toward belonging.

But his own daughters grow up estranged.

Sandra moves through echoes of brutality.

Selmor meanders through the shadows of neglect.

The embrace he sang about never reached them.

A voice that promised care, awareness, pride.

A man that delivered none.

9/

The catalogue is immense.

He sings of nurture.

He sings of dignity.

He sings of justice.

Yet the man behind the songs is a contradiction.

Each lyric a mask.

Each anthem a silence he could not break.

He sings words he never seemed to believe — words that were never meant at all.

The catalogue is immense.

He sings of nurture.

He sings of dignity.

He sings of justice.

Yet the man behind the songs is a contradiction.

Each lyric a mask.

Each anthem a silence he could not break.

He sings words he never seemed to believe — words that were never meant at all.

10/

Here is the tragedy.

A boy from Highfield becomes Africa’s voice.

A griot of pain and joy.

A healer in song.

But also a cruel, selfish man in life.

Tuku dies in Harare.

23 January 2019.

At his tribute at Pakare Paye Arts Centre, Selmor breaks down in song — a daughter visibly overwhelmed by pain.

The state crowns him a national hero.

Here is the tragedy.

A boy from Highfield becomes Africa’s voice.

A griot of pain and joy.

A healer in song.

But also a cruel, selfish man in life.

Tuku dies in Harare.

23 January 2019.

At his tribute at Pakare Paye Arts Centre, Selmor breaks down in song — a daughter visibly overwhelmed by pain.

The state crowns him a national hero.

11/

The hero’s an enigma.

A voice of reason, tradition, and song.

Yet a hollow conscience at home.

A man of many faces.

He gave Zimbabwe its soundtrack — weddings, funerals, rallies, nightclubs.

But he left his daughters wounded.

His family divided.

His daughters embody every woman and girl he once sang for — every progressive, caring, loving value Zimbabweans stand for.

By letting Sandra and Selmor down, he let us all down.

Tuku.

The voice that betrayed Zimbabwe

The hero’s an enigma.

A voice of reason, tradition, and song.

Yet a hollow conscience at home.

A man of many faces.

He gave Zimbabwe its soundtrack — weddings, funerals, rallies, nightclubs.

But he left his daughters wounded.

His family divided.

His daughters embody every woman and girl he once sang for — every progressive, caring, loving value Zimbabweans stand for.

By letting Sandra and Selmor down, he let us all down.

Tuku.

The voice that betrayed Zimbabwe

12/

Sources

— In Memoriam: Dr Oliver ‘Tuku’ Mtukudzi (1952–2019) — Zimbabwe International Journal of Language & Culture

— Music and Human Rights in Zimbabwe: An Analysis of Oliver Mtukudzi’s Messages — Lazarus Sauti

— Domestic Violence, Alcohol and Child Abuse through Popular Music in Zimbabwe: A Decolonial Perspective

— BBC / Al Jazeera / Reuters obituaries

— Interviews with Sandra and Selmor Mtukudzi

Sources

— In Memoriam: Dr Oliver ‘Tuku’ Mtukudzi (1952–2019) — Zimbabwe International Journal of Language & Culture

— Music and Human Rights in Zimbabwe: An Analysis of Oliver Mtukudzi’s Messages — Lazarus Sauti

— Domestic Violence, Alcohol and Child Abuse through Popular Music in Zimbabwe: A Decolonial Perspective

— BBC / Al Jazeera / Reuters obituaries

— Interviews with Sandra and Selmor Mtukudzi

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh