Thread: For those of us in math, science or philosophy, there are often a chosen few books which serve as "gateway drugs" during formative years. For me, one of the few such gateway drugs was Penrose's "The Emperor's New Mind" which I first discovered in college.

When I first The Emperor’s New Mind, it felt magical, as if I had just entered a new universe. I’d vaguely heard about quantum mechanics, Gödel, and general relativity, but Penrose didn’t just explain them. He opened a door, and suddenly there was an entire landscape behind it.

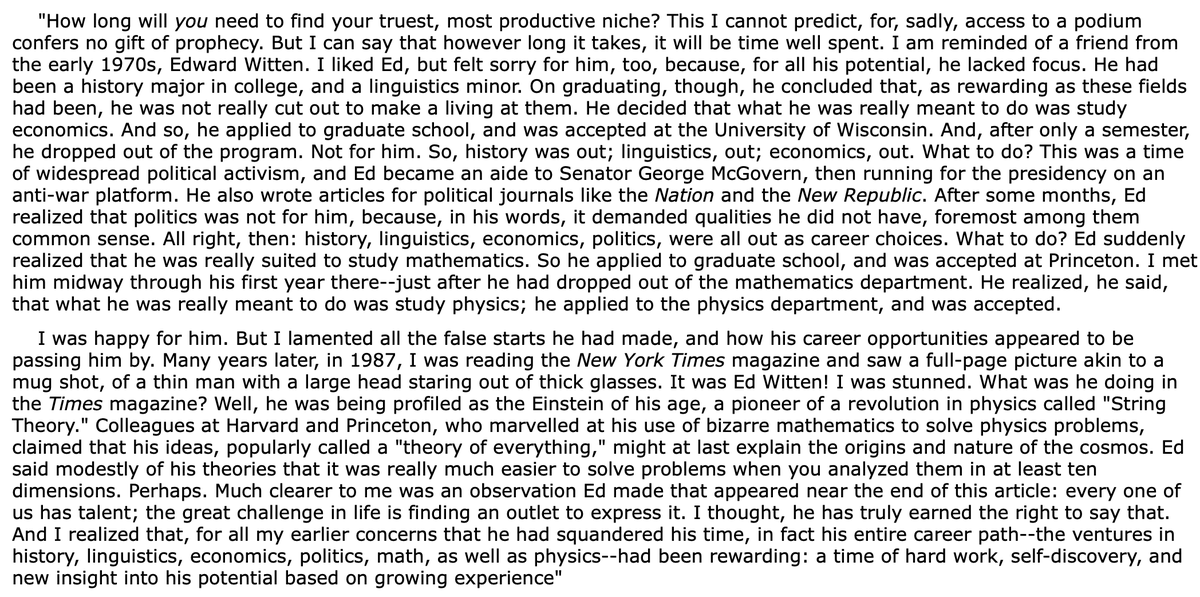

What makes Penrose special is that he’s not just a brilliant explainer. He’s both interpreter and architect: he walks you through vast domains of physics, math, computer science, and neuroscience, then builds his own original theory atop them.

Where Greene’s The Elegant Universe or Hawking's A Brief History of Time are masterful tours through an existing landscape, Penrose is drawing the map as you walk with him. He’s not merely surveying knowledge, he’s constructing a bold, coherent vision of reality.

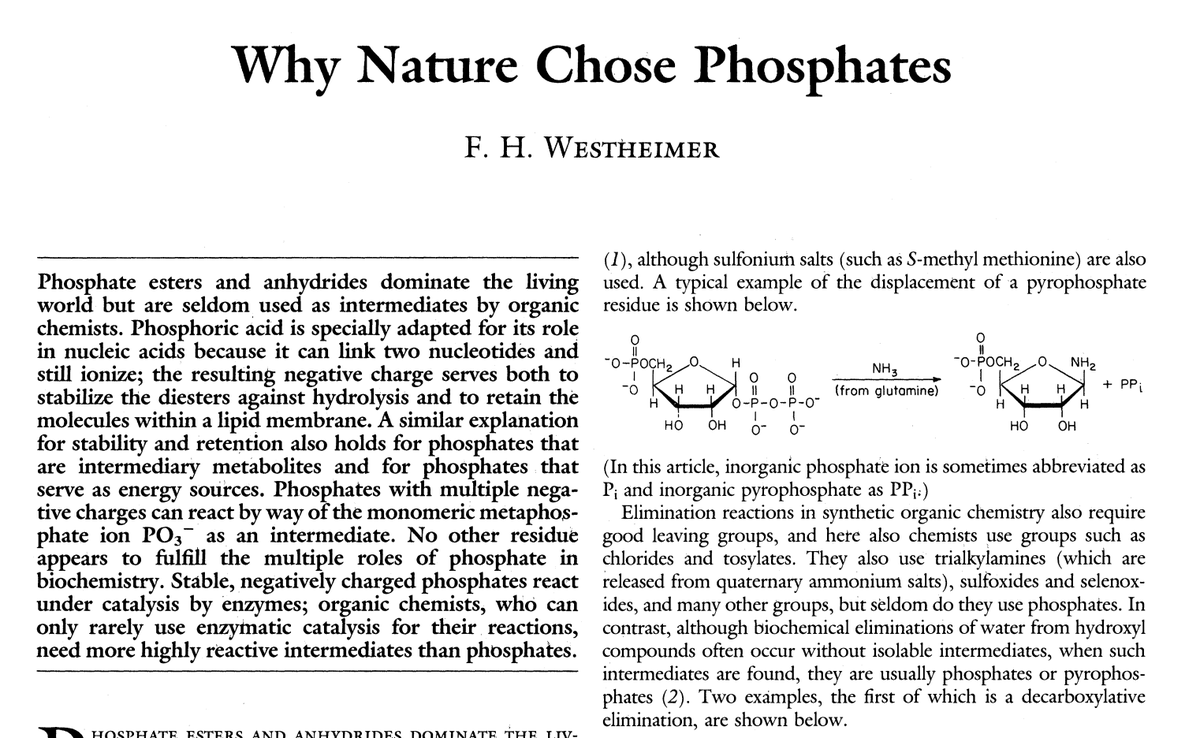

He fuses rigorous reasoning with bold leaps: Gödel’s incompleteness, Turing machines, quantum mechanics, consciousness, and quantum gravity all become pieces in his argument. Whether his arguments are right or wrong is secondary: it's the imagination and brilliance that stick out

For a young college student who had vaguely heard of these things and knew they were exciting, it was like being given a key to a magic kingdom. You didn't understand everything in it, and maybe some of it was a mirage, but the sheer view was exhilarating.

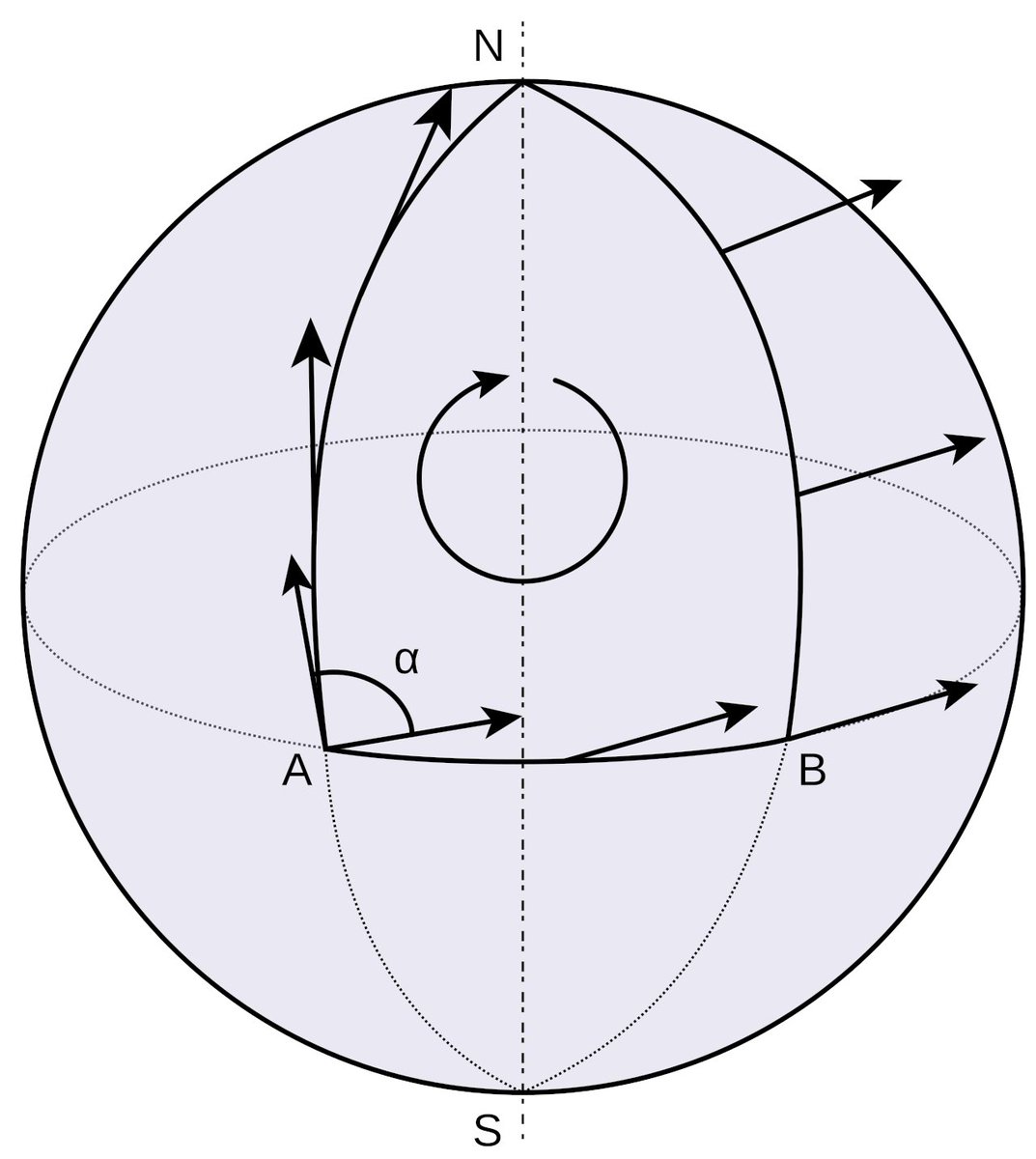

Perhaps best of all, Penrose doesn’t sugarcoat or oversimplify. He gives you actual arguments, sketches proofs, draws Penrose diagrams. It’s like being invited into a grown-up intellectual conversation for the first time, peeking behind the curtain of real science.

Penrose writes like a 19th-century natural philosopher: uniting math, physics, and philosophy with audacious synthesis. That’s why it stays with you long after the details fade. You’re not just reading Penrose. You’re thinking alongside him. The experience was unforgettable.

Even today when someone, say a parent, asks me if I have a recommendation for their son or daughter to get excited about science I recommend The Emperor's New Mind, not to understand modern physics or math or philosophy of science but to get a taste of how amazing it all is.

There are a few others like that: books which are more magical experience than anything else. The Feynman Lectures, "Gödel, Escher, Bach", John Casti's "Paradigms Lost" were others that shook me to the core, each in its own way. None are easy, all are a gateway drug.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh