Everyone knows 1066 ended Saxon England.

Few remember what came after.

Because not all of Harold’s men died at Hastings. Many sailed south, toward the one realm where warriors like them still had a place

To Byzantium

To the Emperor's court in Constantinople

A thread🧵

Few remember what came after.

Because not all of Harold’s men died at Hastings. Many sailed south, toward the one realm where warriors like them still had a place

To Byzantium

To the Emperor's court in Constantinople

A thread🧵

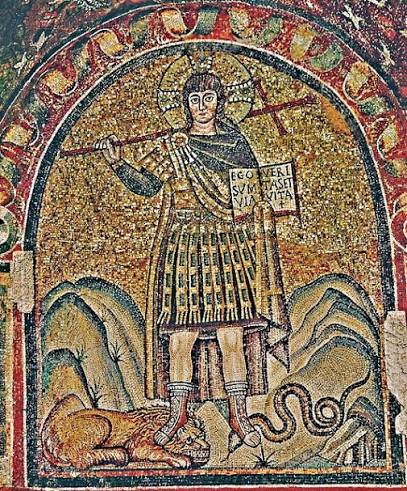

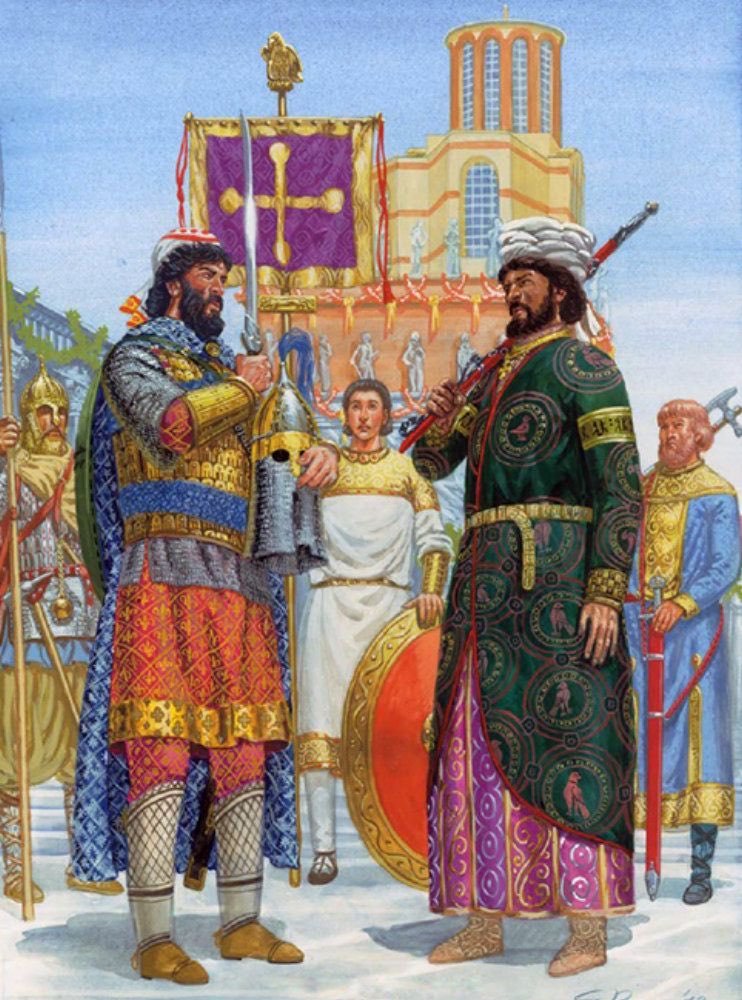

The proud warriors of Harold Godwinson, the last Saxon king of England, ended in the realm known to its people as “Basileia Rhōmaiōn” - THE Roman Empire.”

Here, those exiles found new masters, new purpose, and in time, a new identity. /1

Here, those exiles found new masters, new purpose, and in time, a new identity. /1

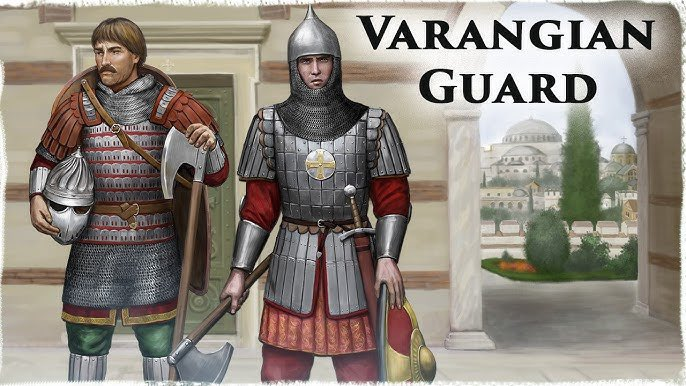

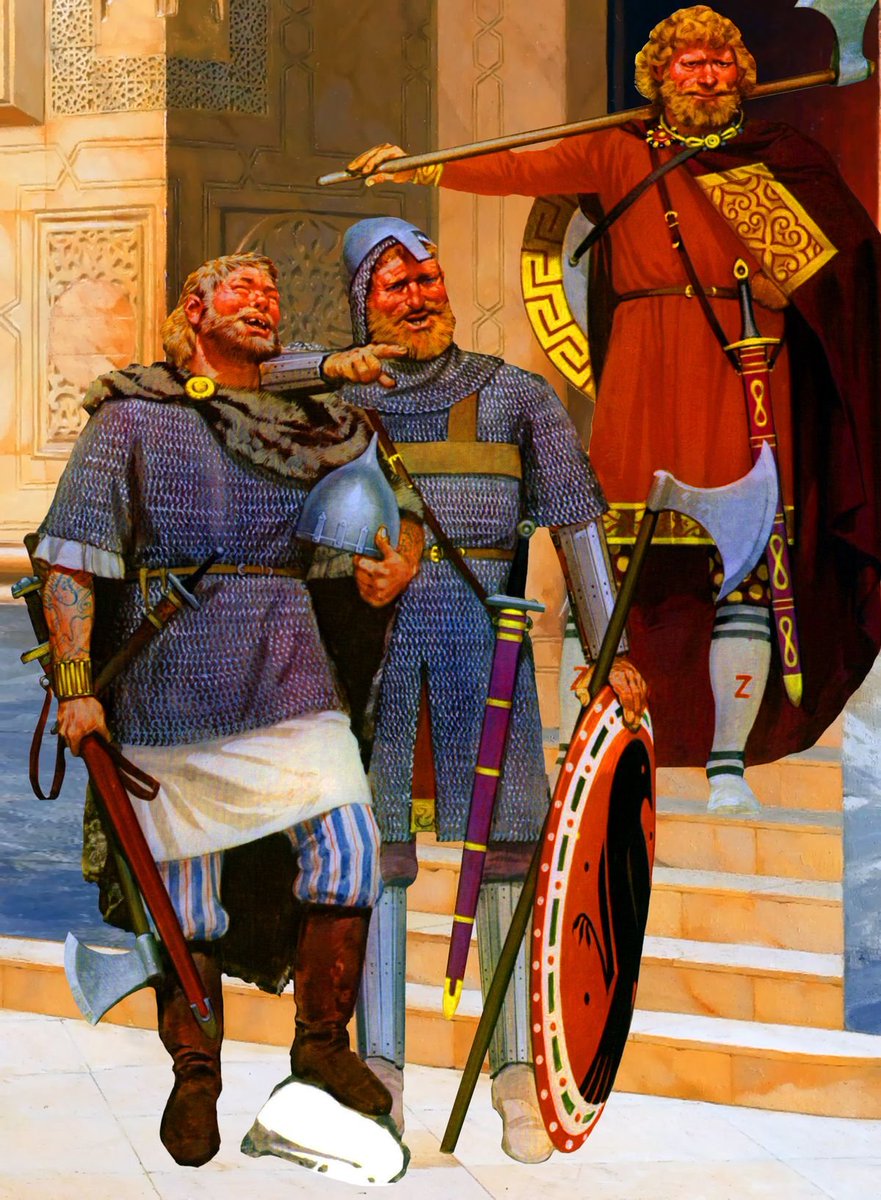

The Byzantines called the visitors from the North Varangians- the fearsome bodyguards of the Emperor. The finest warriors of the Middle Ages.

Tall, broad-shouldered men with long axes, guarding the marble halls of the Great Palace and the Empire’s blood-soaked frontiers. /2

Tall, broad-shouldered men with long axes, guarding the marble halls of the Great Palace and the Empire’s blood-soaked frontiers. /2

The Anglo-Saxons were not the first Varangians. Before them came the Rus, and then the Norse. But after Hastings, they took primacy - calling themselves Englinbarrangoi, the “English Varangians,.

Keeping their tongue and customs alive in the East /3

Keeping their tongue and customs alive in the East /3

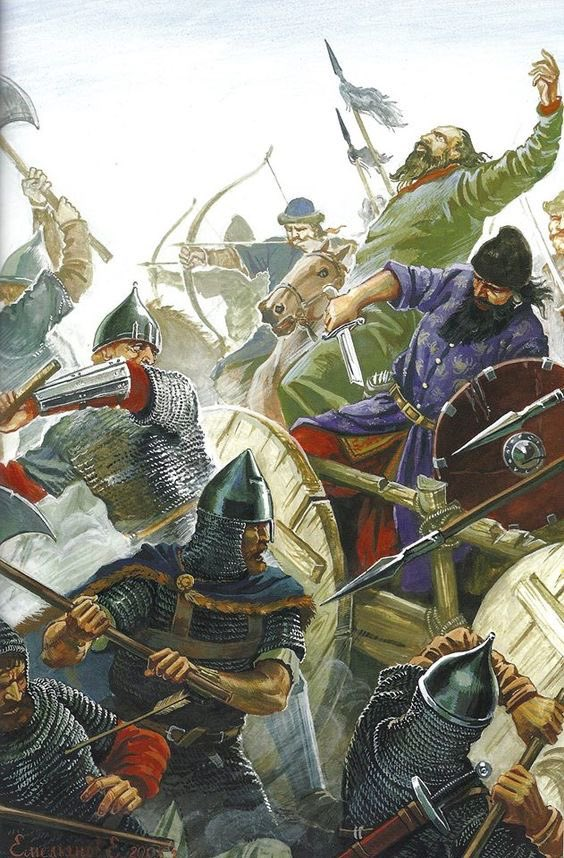

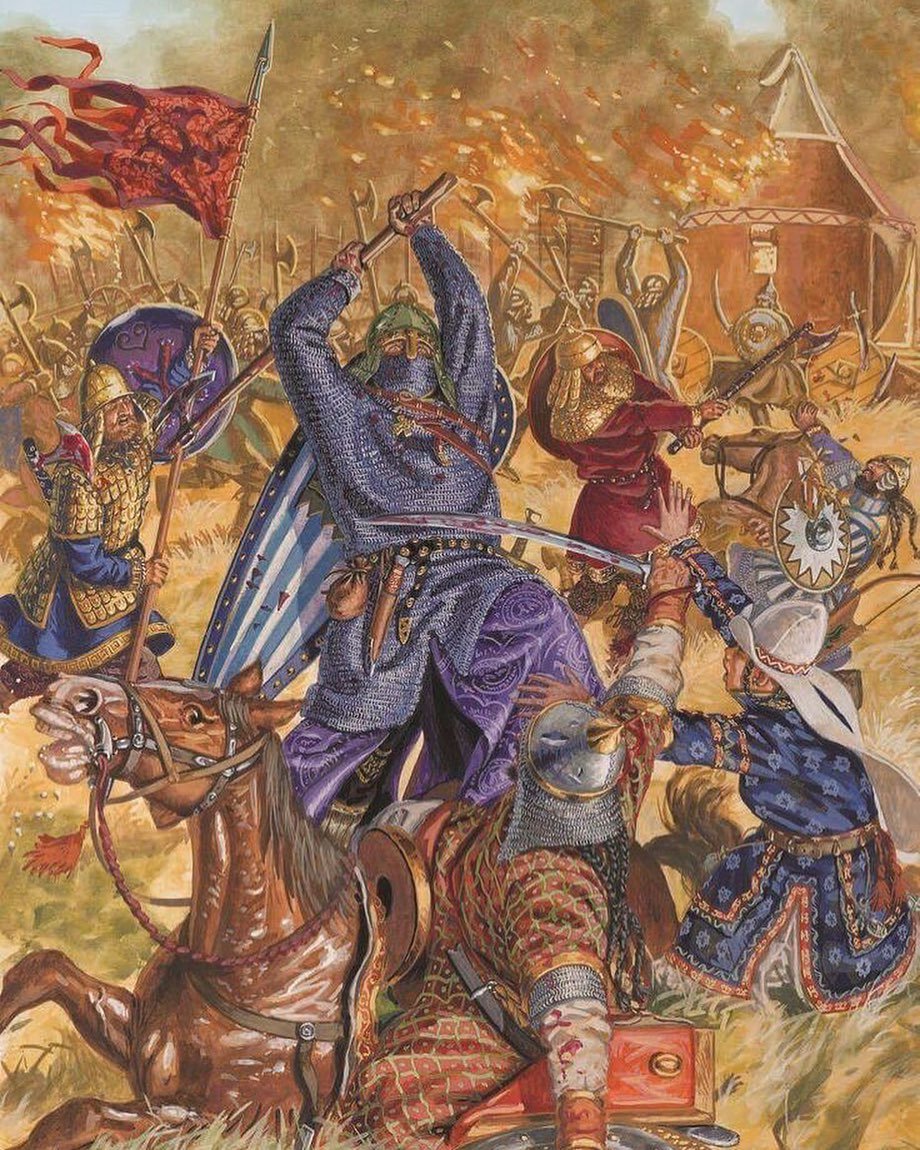

But while at Hastings they lost their home, in the emperor's service, those men found their new purpose. A crack military unit, fearless, devoted and unmatched on the battlefield

And their new enemy? The Normans.

Old wounds reopened, now with imperial backing. /4

And their new enemy? The Normans.

Old wounds reopened, now with imperial backing. /4

We meet them on campaign quickly. In 1081, at Dyrrhachium, the Varangians - many fresh from England - smashed Robert Guiscard’s Norman left before being surrounded and cut down.

Anna Komnene admired them deeply: huge, loyal, brave barbarians who died to the last man... /5

Anna Komnene admired them deeply: huge, loyal, brave barbarians who died to the last man... /5

Alexios Komnenos barely escaped that day.

Yet he never forgot his saviors.

Soon, English Varangians fought at Levounion (1091) against the Pechenegs, and later at Beroia (1122) - a decisive Roman victory that restored imperial power in the Balkans. /6

Yet he never forgot his saviors.

Soon, English Varangians fought at Levounion (1091) against the Pechenegs, and later at Beroia (1122) - a decisive Roman victory that restored imperial power in the Balkans. /6

Thus it is not a surprise that the Romans welcomed the Northern refugees with open arms.

Some sources claim that over 5,000 arrived in 235 ships (!)

Those who did not enter imperial service settled on the Black Sea coast, building and garrisoning the town of Helenopolis. /7

Some sources claim that over 5,000 arrived in 235 ships (!)

Those who did not enter imperial service settled on the Black Sea coast, building and garrisoning the town of Helenopolis. /7

In the Guard, the English were famed not only for their axes but also as skilled horsemen.

When not campaigning, they were stationed in the Bukoleon Palace - watching over the Great Palace complex that overlooked the Bosporus. /8

When not campaigning, they were stationed in the Bukoleon Palace - watching over the Great Palace complex that overlooked the Bosporus. /8

High-born exiles found their way too. According to some scholars, Edgar Ætheling, last male of the old royal line, appeared at Alexios’ court.

Others with recognizably English names surface in records in Greek forms, rising through merit and long service to command posts. /9

Others with recognizably English names surface in records in Greek forms, rising through merit and long service to command posts. /9

Inside the corps, English customs survived.

Imperial chroniclers noted their distinct language, their fondness for ale, their loudness, their blunt discipline.

To the Romans, none of that mattered.

Only one thing did: their sacred oath to the emperor. /10

Imperial chroniclers noted their distinct language, their fondness for ale, their loudness, their blunt discipline.

To the Romans, none of that mattered.

Only one thing did: their sacred oath to the emperor. /10

By the 12th century, Latin observers sometimes call the Guard “the English of the Emperor.”

And in 1204, when the Crusaders stormed Constantinople, the last Varangians - descendants of the Hastings exiles - fought to the death to defend doomed city. /11

And in 1204, when the Crusaders stormed Constantinople, the last Varangians - descendants of the Hastings exiles - fought to the death to defend doomed city. /11

The Sack of Constantinople, the fall of the City, was also the end of the Anglo-Saxon Varangians.

Some probably survived in Nicaea or Epirus. Yet, while the Guard endured, the brave Englishmen faded from the record. /12

Some probably survived in Nicaea or Epirus. Yet, while the Guard endured, the brave Englishmen faded from the record. /12

If that obituary made you smile, this is the sober afterpiece

King Harold fell, but many of his men did not. They sailed south, swore new oaths - and for a century and more their axes stood between the Emperor and his enemies.

Until their watch ended.

/Fin

King Harold fell, but many of his men did not. They sailed south, swore new oaths - and for a century and more their axes stood between the Emperor and his enemies.

Until their watch ended.

/Fin

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh