In 1260, the Mongols would make their move into the Levant, but meet their match and face their first major defeat.

This is a thread on the battle of Ain Jalut!

This is a thread on the battle of Ain Jalut!

By 1259 the Mongols had overrun much of the Islamic world. They had conquered Persia, defeated the Seijuks in Anatolia and just a year prior sacked the centre of the Muslim world, Baghdad, killing the caliph and massacring hundreds of thousands of others. They seemed unstoppable, and were determined to march south and expand into the Levant region and Egypt.

Both the Levant and Egypt had recently been taken over by the Mamluks, a military division of mostly non-Arabic former slaves. Trained in war, they were a formidable force, and under their new sultan Qutuz were determined to face off the Mongol threat. The leader of the Mongols in West Asia, Hulegu Khan, sent Qutuz envoys demanding he surrender Egypt but the defiant sultan executed them and displayed their heads on the walls of Cairo.

The two sides seemed set for a clash. Huelgu moved south, but then recieved news that the Great Khan, Mongke, had died on campaign in China. As a contender for the elective title, Hulegu had to return to Mongolia if he wanted to be considered, and that he did, taking the bulk of his army with him. He left some 10,000 troops west of the Euphrates under the command of his deputy Kitbuga.

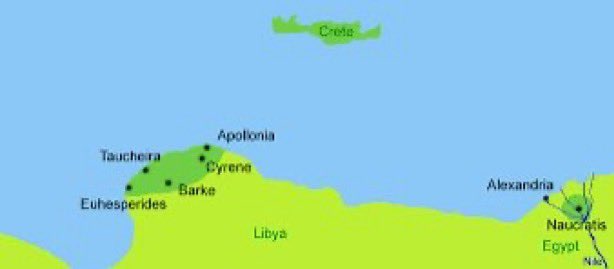

Hearing of this development, Qutuz seized his chance and amassed a force of some 15-20000 strong, setting out to combat Kitbuga from Cairo in July of 1260. Qutuz’ force marched towards Gaza quickly, eager to prevent the Mongols from taking the strategic town. He marched past Jerusalem and the Crusader States (which had no love for the Mamluks but, worried by the record of Mongol atrocities, decided not to side with them and let him have safe passage).

Kitbuga had hoped to take Gaza and was disheartened when he found he was too late, but decided to proceed anyway and invaded Syria. The two forces approached each other and eventually met at the spring of Ain Jalut in the Valley of Jezreel in September. The Mongols arrived first and took a position along the slopes. Qutuz and his deputy, the fellow Mamluk Baybars, spotted their camp shortly after and assembled their forces.

The battle began on September 3rd. The Mongols launched an assault but it soon became clear a smaller part of the Mamluk army was in open field, commanded by Baybars. Qutuz kept the bulk of his army in reserve, hoping the Mongols would tire first. The Mamluks used the strategy of hit and run, using smaller units to assault the Mongols to draw them into open field (ironically a strategy the Mongols with their famed calvary had used many times before against their enemies). For once they had met a foe immune to their traditional strategy.

Eventually, Kitbuga became convinced that Baybars was fleeing the field and sent his army in full force to chase, which was a fateful mistake as they were soon drawn into the centre of Jezreel Valley. At that point Qutuz sprang his trap and his remaining army emerged from hiding, surrounding the Mongol force from the above slopes and firing allows into their helpless troops.

The Mongols made a valiant attempt to break out of their encirclement, coming close at times, but Qutuz’ force held firm and all of their attempts were ultimately repulsed. The Mongol force was wiped out and Kitbuga was captured and brought before Qutuz. After making defiant statements mocking the Mamluks for their status as usurpers, he was beheaded

While Ain Jalut was a major defeat for the Mongols it was not so much the defeat itself as the aftermath that made it mark the limits of Mongol expression. The Mamluks expected retaliation, but Hulegu was distracted by the Khanate election, and then the Mongol empire fell into civil war not long afterwards making him returning to avenge the humiliation impossible. The Mongols would later launch raids into the Levant as late as the 1290s, sacking Aleppo and Homs at times, but never established a permanent presence, and eventually the conversion of the sub-branch known as the Illkhanate to Islam made them abandon their attacks on their fellow Muslims

The Mamluks were able to advance north after the battle, taking Damascus and Aleppo quickly. Despite his success in repulsing the Mongols, Qutuz was assassinated in Cairo a month later, possibly by Baybars, who succeeded him. The victory cemented their status as the leading power in the Muslim world, and within a few years they would turn their attention to finishing off the Crusader States for good.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh