One evening in the early 1960s, a graduate student from Princeton named Robert Nozick walked into an apartment on West 88th Street in Manhattan.

He was there to meet Murray Rothbard, the radical economist who believed all government was illegitimate theft.

That night changed the history of political philosophy. 🧵

He was there to meet Murray Rothbard, the radical economist who believed all government was illegitimate theft.

That night changed the history of political philosophy. 🧵

Robert Nozick was a conventional social democrat. Smart, ambitious, headed for a prestigious academic career. He believed in welfare programs, redistribution, the New Deal consensus.

Everything a respectable New York Jewish intellectual was supposed to believe.

Then he met Bruce Goldberg at Princeton.

Everything a respectable New York Jewish intellectual was supposed to believe.

Then he met Bruce Goldberg at Princeton.

Bruce Goldberg was different. A philosophy grad student from City College, he was a missionary for ideas most people thought insane. Free markets without any government intervention. Private courts. Competing police forces.

Goldberg had been converted to libertarianism by his friend Ralph Raico, who introduced him to the works of Ludwig von Mises and Murray Rothbard.

Now Goldberg was after bigger game.

Goldberg had been converted to libertarianism by his friend Ralph Raico, who introduced him to the works of Ludwig von Mises and Murray Rothbard.

Now Goldberg was after bigger game.

Nozick and Goldberg became close friends. Both brilliant dialecticians, both obsessed with getting to the truth. But Goldberg had something Nozick didn't: a complete philosophical framework that explained why the state was fundamentally illegitimate.

Goldberg lent Nozick books. Mises. Hayek. Hazlitt. Rothbard.

Nozick, intellectually omnivorous, devoured them all. And began asking dangerous questions.

Goldberg lent Nozick books. Mises. Hayek. Hazlitt. Rothbard.

Nozick, intellectually omnivorous, devoured them all. And began asking dangerous questions.

One day Nozick went back to his old friends at Dissent magazine, the intellectual home of American democratic socialism. Michael Harrington, Irving Howe, the best minds of the progressive left.

He asked them: "If the minimum wage is so beneficial, why not set it at $10 an hour?"

These were lifelong professional socialists, widely published, deeply respected. They had no answer. They couldn't even proceed past the first stage of the argument.

He asked them: "If the minimum wage is so beneficial, why not set it at $10 an hour?"

These were lifelong professional socialists, widely published, deeply respected. They had no answer. They couldn't even proceed past the first stage of the argument.

Nozick started rethinking everything. The foundations of his political beliefs were crumbling under the weight of questions he'd never considered before.

But he hadn't yet met the source. The man who'd synthesized these radical ideas into a comprehensive system.

Bruce Goldberg decided it was time to introduce his friend to Murray Rothbard.

But he hadn't yet met the source. The man who'd synthesized these radical ideas into a comprehensive system.

Bruce Goldberg decided it was time to introduce his friend to Murray Rothbard.

The Circle Bastiat met at Rothbard's apartment. A rotating cast of young libertarian intellectuals gathering to discuss economics, philosophy, and the radical reimagining of society.

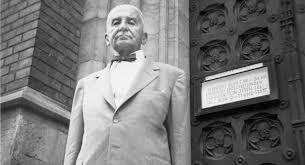

Rothbard was magnetic. Brilliant, funny, uncompromising. He had taken Austrian economics and anarchist political theory and welded them into something new: anarcho-capitalism. The idea that everything government did could be done better by voluntary cooperation and free markets.

Even protection and courts.

Rothbard was magnetic. Brilliant, funny, uncompromising. He had taken Austrian economics and anarchist political theory and welded them into something new: anarcho-capitalism. The idea that everything government did could be done better by voluntary cooperation and free markets.

Even protection and courts.

Nozick walked into that meeting a social democrat questioning his assumptions.

He left it electrified. This wasn't just economic theory or abstract philosophy. This was a complete challenge to everything he'd been taught about the legitimacy of state power.

As Ralph Raico later wrote: "This was the genesis of his celebrated book."

If Nozick hadn't been impressed before, he was after that night.

He left it electrified. This wasn't just economic theory or abstract philosophy. This was a complete challenge to everything he'd been taught about the legitimacy of state power.

As Ralph Raico later wrote: "This was the genesis of his celebrated book."

If Nozick hadn't been impressed before, he was after that night.

Here's what's extraordinary: Rothbard had argued that the state was nothing more than a criminal gang, that taxation was theft, that all government services should be privatized including police and courts.

Nozick couldn't fully accept this. But he couldn't dismiss it either. The Rothbardian challenge was too intellectually serious, too carefully reasoned.

So Nozick set out to answer it.

Nozick couldn't fully accept this. But he couldn't dismiss it either. The Rothbardian challenge was too intellectually serious, too carefully reasoned.

So Nozick set out to answer it.

"Anarchy, State, and Utopia" is fundamentally a response to Murray Rothbard, though you wouldn't know it from how academics discuss the book.

The entire first section of the book starts from the anarcho-capitalist position. Nozick takes competing private defense agencies seriously, treats them as the baseline, and then tries to show how a minimal state could arise from that framework without violating anyone's rights.

This was revolutionary.

The entire first section of the book starts from the anarcho-capitalist position. Nozick takes competing private defense agencies seriously, treats them as the baseline, and then tries to show how a minimal state could arise from that framework without violating anyone's rights.

This was revolutionary.

No mainstream political philosopher had ever done this before. The legitimacy of the state was simply assumed. You started with government and asked what it should do.

Nozick, influenced by that evening with Rothbard and the Circle Bastiat, refused to grant that assumption. He made defenders of state power justify every function from scratch.

This is why the book scandalized the establishment.

Nozick, influenced by that evening with Rothbard and the Circle Bastiat, refused to grant that assumption. He made defenders of state power justify every function from scratch.

This is why the book scandalized the establishment.

The irony is brutal. Most academics who discuss Nozick have never heard of Murray Rothbard. They don't know about Bruce Goldberg. They don't know about that meeting on West 88th Street.

They attribute the idea of competing protection agencies to Nozick himself, unaware that he was engaging with and ultimately rejecting a fully developed anarcho-capitalist theory.

The footnotes pointed to Rothbard. Almost no one followed the trail.

They attribute the idea of competing protection agencies to Nozick himself, unaware that he was engaging with and ultimately rejecting a fully developed anarcho-capitalist theory.

The footnotes pointed to Rothbard. Almost no one followed the trail.

Nozick ultimately concluded that a minimal state was legitimate and could arise without rights violations. Rothbard remained an anarchist until his death, convinced Nozick had failed to justify state monopoly on force.

But the encounter between them changed philosophy. It forced the question: why should there be a state at all? What gives any government the right to claim a monopoly on the legitimate use of force?

But the encounter between them changed philosophy. It forced the question: why should there be a state at all? What gives any government the right to claim a monopoly on the legitimate use of force?

One evening. One apartment. One meeting between a questioning grad student and a radical economist.

The result: a book that brought libertarian ideas into the academic mainstream and made the legitimacy of government something that had to be argued for, not simply assumed.

Sometimes the most important conversations happen in living rooms, not lecture halls.

The result: a book that brought libertarian ideas into the academic mainstream and made the legitimacy of government something that had to be argued for, not simply assumed.

Sometimes the most important conversations happen in living rooms, not lecture halls.

If you enjoyed this story of how ideas spread through personal connections and courageous questions, RT it to others who care about intellectual history. And follow for more threads on the hidden encounters that changed how we think about freedom and power.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh