Your credit card rewards exist because someone else is paying 25% APR. Cap that at 10% and the points don’t survive.

I spent years working inside fintech and card programs. That interest margin is the invisible buffer that makes rewards, lounges, and credits pencil out.

Capping credit card APRs at 10% sounds like an obvious consumer win. Cards charge 20 to 30%, many consumers revolve balances, and the system feels punitive.

But credit card economics are not just about interest rates. They are a cross-subsidized system where revolvers subsidize transactors, rewards rely on behavioral inefficiency, and risk-based pricing subsidizes access.

Remove one leg of that stool and the system does not become fairer; it rebalances. And the costs show up where consumers notice most.

Lets look at how this would impact 3 programs

1. AMEX Platinum

A 10% credit card APR cap would not make your card cheaper or better. You would still have access, but you would almost certainly get less value for the same or higher price.

The Platinum brand survives because its customers are affluent, pay in full, and tolerate high annual fees. What quietly supports that ecosystem is portfolio-level profitability, which allows AMEX to tolerate loss, overuse, and inefficiency in premium benefits.

When that margin shrinks, the cost shows up directly in your (lesser) benefits.

In a world where:

- Rewards economics tighten

- Devaluations become more likely

- Flexibility is reduced

Points become a liability to the issuer, and liabilities get repriced.

So what this likely means for you as a Platinum cardholder:

- Lounges do not expand to fix crowding. Instead, access tightens or amenities are reduced.

- Statement credits become harder to use, more fragmented, or less generous.

- Annual fees go up

- New approvals become more selective, even for high earners.

Your card still works, but the value proposition shifts. Platinum becomes more explicitly pay-to-play, with fewer hidden subsidies propping up premium perks.

You pay the same or more, and you get a little less in return.

Which is why some people are already warning that points devaluations become more likely in this environment (like @BowTiedBull this morning saying "Dump ALL your credit card points. All of them.")

2. Bilt Card

This program is the canary in the coal mine for what to expect.

Bilt’s super popular rent rewards worked because Wells Fargo was willing to subsidize them. The card offered 1 point per dollar on rent with no fees because Wells Fargo paid Bilt roughly 0.8 percent (80 bps) of each rent payment to fund rewards... despite earning little or no interchange on those transactions.

But that is some actuarial level math with a number of variables at risk that proved wrong/ unsustainable.

Wells Fargo was getting hosed $10 million a month on the program, so they exited the partnership years before the original end date and forced Bilt to restructure its rewards with a different bank

What does that teach us?

- When interest and interchange margins shrink, banks stop tolerating loss-leading reward programs.

- Interest income does not fund every reward directly, but it provides the buffer that allows experiments like Bilt to exist at all.

- Remove that buffer and rewards must be paid for explicitly.

Bilt’s shift to a three-tier lineup with annual fees is not an anomaly. It is the direction rewards go when credit stops quietly absorbing losses.

Pay-to-play rewards.

What feels like consumer protection will shows up as fewer perks, pay-to-play rewards, and less room for innovation.

3. Credit One & other Subprime Cards

Now the least glamorous corner.

Subprime cards get criticized for high APRs, annual fees, low limits, minimal rewards. But they exist for a reason.

They serve thin-file borrowers, damaged credit, people shut out of conventional loans, households using cards for liquidity not perks... but they charge high APRs because charge-offs exceed 8-10%, fraud and servicing costs are higher, and credit limits are small while fixed costs remain significant.

A 10% cap makes these products mathematically impossible.

These cards don't become cheaper. They cease to exist.

As @sytaylor noted this morning - "You realize this will push many more customers towards loan sharks?"

The demand for credit doesn't disappear... it migrates to BNPL with opaque effective APRs, chronic overdraft usage, fee-heavy installment loans, and less regulated lenders like loan sharks/ payday loans.

So who WOULD win? Debit-First Fintechs

One of the least discussed consequences: where would reward customers migrate?

I think 1% cashback programs are an obvious winner. Chime, Varo, Current and niche cards like Greenlight and Privacy.

(If you have not worked in a fintech or a bank you probably don't know what the Durbin Amedment is - but the TL;DR is that very large banks (BoA, Wells, JPMC) have capped interchange rates of around 27 bps on debit swipes.

Small banks with < $10B AUM, however, do not - they can earn 1-2% on interchange (avg was 160 bps or so last I checked).

Which is why all of the debit card fintech companies you've heard of are partnered with these smaller banks - they can offer rewards like 1% cashback programs and still have margin sufficient to build a business around.)

In a world where credit rewards shrink, access tightens, and annual fees rise, debit-based fintechs look better by comparison.

But consumers lose: credit protections, payment float, stronger dispute rights, credit-building opportunities.

TL;DR

An APR cap feels like consumer protection.

In practice it reshapes the market in ways that are easy to miss:

- It will shrink access to credit

- Eliminate rewards programs that aren't tied to high annual fees

- Force risk into less regulated channels

- Unintentionally advantages debit over credit

- Help affluent transactors more than vulnerable borrowers

Credit doesn't become cheaper. It becomes scarcer, less flexible, less transparent.

But banks will adapt.

Fintechs will adapt.

Consumers caught in the middle do not get protected.

They get fewer choices, worse products, and priced out.

I spent years working inside fintech and card programs. That interest margin is the invisible buffer that makes rewards, lounges, and credits pencil out.

Capping credit card APRs at 10% sounds like an obvious consumer win. Cards charge 20 to 30%, many consumers revolve balances, and the system feels punitive.

But credit card economics are not just about interest rates. They are a cross-subsidized system where revolvers subsidize transactors, rewards rely on behavioral inefficiency, and risk-based pricing subsidizes access.

Remove one leg of that stool and the system does not become fairer; it rebalances. And the costs show up where consumers notice most.

Lets look at how this would impact 3 programs

1. AMEX Platinum

A 10% credit card APR cap would not make your card cheaper or better. You would still have access, but you would almost certainly get less value for the same or higher price.

The Platinum brand survives because its customers are affluent, pay in full, and tolerate high annual fees. What quietly supports that ecosystem is portfolio-level profitability, which allows AMEX to tolerate loss, overuse, and inefficiency in premium benefits.

When that margin shrinks, the cost shows up directly in your (lesser) benefits.

In a world where:

- Rewards economics tighten

- Devaluations become more likely

- Flexibility is reduced

Points become a liability to the issuer, and liabilities get repriced.

So what this likely means for you as a Platinum cardholder:

- Lounges do not expand to fix crowding. Instead, access tightens or amenities are reduced.

- Statement credits become harder to use, more fragmented, or less generous.

- Annual fees go up

- New approvals become more selective, even for high earners.

Your card still works, but the value proposition shifts. Platinum becomes more explicitly pay-to-play, with fewer hidden subsidies propping up premium perks.

You pay the same or more, and you get a little less in return.

Which is why some people are already warning that points devaluations become more likely in this environment (like @BowTiedBull this morning saying "Dump ALL your credit card points. All of them.")

2. Bilt Card

This program is the canary in the coal mine for what to expect.

Bilt’s super popular rent rewards worked because Wells Fargo was willing to subsidize them. The card offered 1 point per dollar on rent with no fees because Wells Fargo paid Bilt roughly 0.8 percent (80 bps) of each rent payment to fund rewards... despite earning little or no interchange on those transactions.

But that is some actuarial level math with a number of variables at risk that proved wrong/ unsustainable.

Wells Fargo was getting hosed $10 million a month on the program, so they exited the partnership years before the original end date and forced Bilt to restructure its rewards with a different bank

What does that teach us?

- When interest and interchange margins shrink, banks stop tolerating loss-leading reward programs.

- Interest income does not fund every reward directly, but it provides the buffer that allows experiments like Bilt to exist at all.

- Remove that buffer and rewards must be paid for explicitly.

Bilt’s shift to a three-tier lineup with annual fees is not an anomaly. It is the direction rewards go when credit stops quietly absorbing losses.

Pay-to-play rewards.

What feels like consumer protection will shows up as fewer perks, pay-to-play rewards, and less room for innovation.

3. Credit One & other Subprime Cards

Now the least glamorous corner.

Subprime cards get criticized for high APRs, annual fees, low limits, minimal rewards. But they exist for a reason.

They serve thin-file borrowers, damaged credit, people shut out of conventional loans, households using cards for liquidity not perks... but they charge high APRs because charge-offs exceed 8-10%, fraud and servicing costs are higher, and credit limits are small while fixed costs remain significant.

A 10% cap makes these products mathematically impossible.

These cards don't become cheaper. They cease to exist.

As @sytaylor noted this morning - "You realize this will push many more customers towards loan sharks?"

The demand for credit doesn't disappear... it migrates to BNPL with opaque effective APRs, chronic overdraft usage, fee-heavy installment loans, and less regulated lenders like loan sharks/ payday loans.

So who WOULD win? Debit-First Fintechs

One of the least discussed consequences: where would reward customers migrate?

I think 1% cashback programs are an obvious winner. Chime, Varo, Current and niche cards like Greenlight and Privacy.

(If you have not worked in a fintech or a bank you probably don't know what the Durbin Amedment is - but the TL;DR is that very large banks (BoA, Wells, JPMC) have capped interchange rates of around 27 bps on debit swipes.

Small banks with < $10B AUM, however, do not - they can earn 1-2% on interchange (avg was 160 bps or so last I checked).

Which is why all of the debit card fintech companies you've heard of are partnered with these smaller banks - they can offer rewards like 1% cashback programs and still have margin sufficient to build a business around.)

In a world where credit rewards shrink, access tightens, and annual fees rise, debit-based fintechs look better by comparison.

But consumers lose: credit protections, payment float, stronger dispute rights, credit-building opportunities.

TL;DR

An APR cap feels like consumer protection.

In practice it reshapes the market in ways that are easy to miss:

- It will shrink access to credit

- Eliminate rewards programs that aren't tied to high annual fees

- Force risk into less regulated channels

- Unintentionally advantages debit over credit

- Help affluent transactors more than vulnerable borrowers

Credit doesn't become cheaper. It becomes scarcer, less flexible, less transparent.

But banks will adapt.

Fintechs will adapt.

Consumers caught in the middle do not get protected.

They get fewer choices, worse products, and priced out.

Tbc I’m not defending the current system. On a personal level, I don’t have a stake in the outcome and I don’t expect this to be implemented as written.

I’m explaining how payments and credit actually work in the US, incl who pays for what and what that implies.

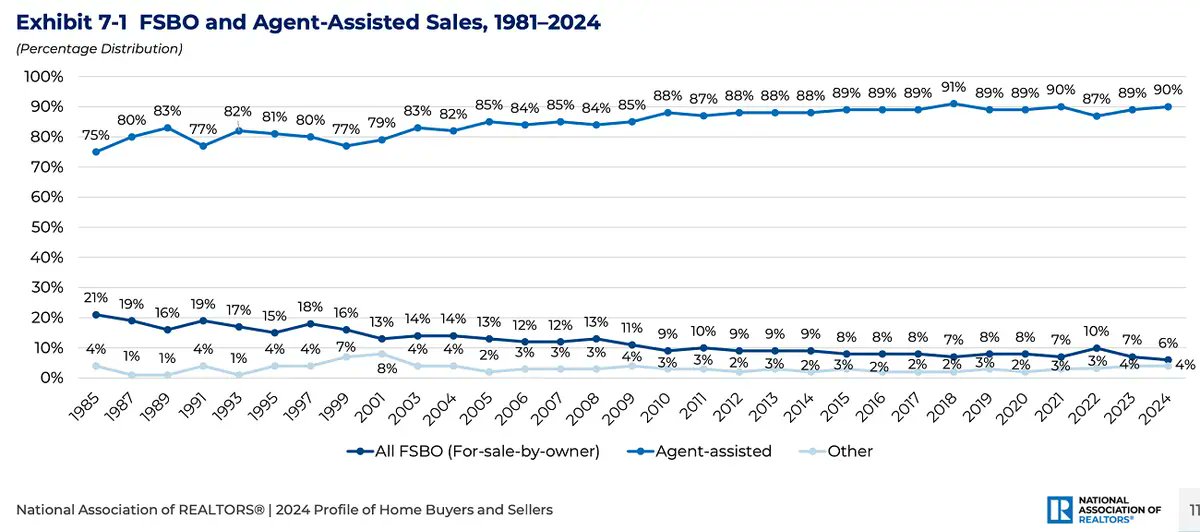

If you pull this lever, here’s what else moves: The US economy is deeply credit-dependent. Credit histories sit underneath mortgages, auto loans, rentals, insurance pricing, and more. Restricting revolving credit does not just change spending behavior. It changes how people qualify for basic financial products.

Ironically, a hard APR cap would push the US toward a more EU-style credit system, with lower margins, fewer rewards, & tighter access.

That model works in Europe because it is built on different assumptions. In the US ... it doesn't achieve the policy’s stated objectives. It reshapes incentives and access in ways that are not obvious unless you’ve worked inside the industry.

I’m explaining how payments and credit actually work in the US, incl who pays for what and what that implies.

If you pull this lever, here’s what else moves: The US economy is deeply credit-dependent. Credit histories sit underneath mortgages, auto loans, rentals, insurance pricing, and more. Restricting revolving credit does not just change spending behavior. It changes how people qualify for basic financial products.

Ironically, a hard APR cap would push the US toward a more EU-style credit system, with lower margins, fewer rewards, & tighter access.

That model works in Europe because it is built on different assumptions. In the US ... it doesn't achieve the policy’s stated objectives. It reshapes incentives and access in ways that are not obvious unless you’ve worked inside the industry.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh