So do Trump's threats against Greenland undermine the political science consensus on the Democratic Peace Theory?

I don't think so, but let's explore this question.🧵

I don't think so, but let's explore this question.🧵

The Democratic Peace Theory posits that liberal democracies have an unusually low tendency to go to war with each other. Though this empirical observation seems to be very overwhelming, the supposed mechanisms to explain it are extremely vague and unconvincing.

Contra the popular understanding, it does not necessarily posit that liberal democracies are not hawkish and aggressive. Few would dispute that many liberal democracies have frequently engaged in militaristic foreign policy, directed at their authoritarian adversaries.

Though the political science consensus continues to be that authoritarian regimes are somewhat more likely to go to war with each other than liberal democracies and authoritarian regimes are to go to war, this is very far from a strong universal truism.

The logical implication of this theory is that the most foolproof way for democracies to ensure their own security is by turning their adversaries into liberal democracies, the most famous example of which would be the transformation of the Axis Powers after World War II.

Another example of this would be the Western-backed 1989 wave of liberal democratic nationalist revolutions which collapsed the communist bloc.

But after the confident predictions of Francis Fukuyama around this time, faith in pro-democratic foreign policy has fallen off.

But after the confident predictions of Francis Fukuyama around this time, faith in pro-democratic foreign policy has fallen off.

High hopes for a Free Russia and a Free China have been dashed since the rise of Vladimir Putin in 1999 and Xi Jinping in 2012.

The US-led state-building projects in Iraq and Afghanistan after the 9/11 attacks achieved only mixed results in Iraq and complete failure in Afghanistan.

Israel's hopes to solve their conflict with the Palestinians through free elections in Palestine were dashed by the victory of Hamas in the 2006 legislative elections, a terrorist organization dedicated to Israel's destruction.

Perhaps most demoralizing of all were the "Arab Spring" wave of revolutions in the Middle East after 2010, which resulted in several catastrophic civil wars in Syria, Libya, Yemen, and Sudan and only in a full democratic transition in one country, Tunisia, which later reversed.

As a general rule, liberal democracy seems to have had much less success in the Middle East than it has elsewhere, though it would be rather oversimplistic to consider this an ironclad rule.

As evidence of this, Israel, the sole liberal democracy in the region, probably has the foreign policy that most heavily cuts against the predictions of the Democratic Peace Theory.

Their behavior towards the Arab states cannot seriously be described as promoting democracy. Indeed, just as often, they have aimed to entrench existing autocratic regimes which they believe to be less hostile than the actual populace of those countries.

Unless democracy actually does something to change the foreign policy behavior and interests of a given regime, then the entire concept of "the Free World," a band of states united by mutual interest in democracy and democracy promotion, is rendered essentially meaningless.

Nonetheless, I would still note that Israel's behavior on the periphery of the Middle East has been more consistent with the theory, such as supporting liberal democratic movements in both Iran and in Somaliland.

Additionally, one might note that the recent foreign policy behavior of Russia and China is indeed strongly consistent with the predictions of the Democratic Peace Theory.

As the internal politics of both countries have changed, they have displayed an extreme hostility to liberal democratic movements on their border, especially to the most culturally connected countries, Taiwan and Hong Kong for China and Belarus and Ukraine for Russia.

This would seem to highlight each regime's fears of a Western-backed liberal democratic color revolution. The more "the Free World" congeals into a cohesive and threatening entity, the more the autocratic nations should likewise do the same in response.

So then, why has the United States' foreign policy behavior changed so much?

The first question to ask is whether the United States is still truly a liberal democracy. This question might seem to have an easy answer but is in fact a subtle issue.

The first question to ask is whether the United States is still truly a liberal democracy. This question might seem to have an easy answer but is in fact a subtle issue.

Once again, we must distinguish the popular idea of a concept from its true academic meaning. Democracy is not defined by past elections, but by the *expectation* of future competitive, free and fair elections.

This is why Nazi Germany, Hamas-run Gaza, and the Chavista regime in Venezuela can be accurately described as fully authoritarian regimes, despite initially coming to power following electoral victories.

Any theory that the reason the Democratic Peace Theory works is due to the inherent benevolence and peacefulness of the masses strikes me as obviously false partly for this reason.

I would tend to attribute it instead to how the incentives of a peaceful transfer of power shift a political culture away from violence and subjugation, but as I acknowledge before I am being speculative here.

Would the leader give up power, were he to lose a free election? This is a difficult thing to anticipate, and a probabilistic judgement.

It is undeniable that the US has undergone authoritarian backsliding at a startling pace since the rise of Donald Trump in 2015-16.

It is undeniable that the US has undergone authoritarian backsliding at a startling pace since the rise of Donald Trump in 2015-16.

Perhaps the strongest piece of evidence that the US is no longer a liberal democracy is Donald Trump's failed attempt at a self-coup in the aftermath of losing the 2020 election, culminating in the violent riot at the US Capitol Building.

I would argue that the US is now essentially a mixed regime, but still has enough constraints on presidential power that it is still more democratic than not, though I accept that reasonable people can disagree on this point.

Indeed the aggression of elements of the US right towards Europe can be interpreted as a retaliation against European efforts to engender a "color revolution" against an increasingly autocratic United States.

Insofar as the US is still democratic, the most democratic factions of the US government, the Democratic Party and the holdover “establishment” elements of the pre-Trump Republican Party, are by far the most opposed to Trump’s desire to seize Greenland.

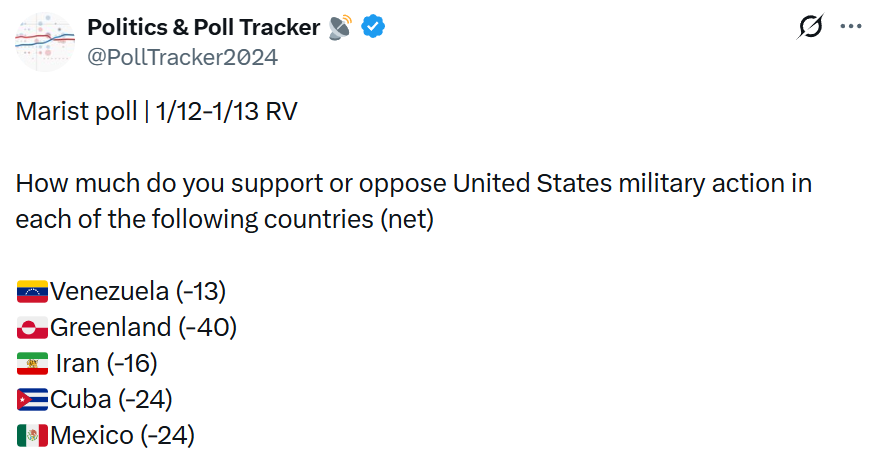

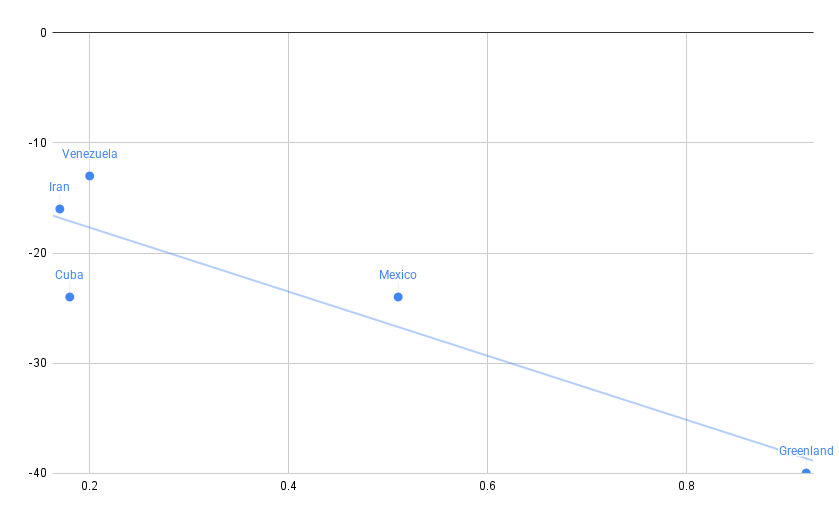

Additionally, the political culture of the United States can still be said to be mostly pro-liberal democratic in its orientation. The support for military action is strongly inversely associated with how democratic that country is (source: V-Dem).

This likely under-rates the association, as the surprisingly high support for military action in Mexico is likely because many poll respondents interpreted military action in Mexico as being against the cartel, rather than aimed at toppling the Mexican government.

This ambiguity also probably over-rated support for invading Greenland. -40 is much higher than other polls have shown, suggesting some Republicans interpreted this as defending Greenland from imaginary threats from Russia and China rather than simply seizing the territory.

It perhaps highlights that the political culture of the United States is still liberal-democratic that Trump feels that to the American public he must attribute the threat to Greenland to Russia and China as opposed to Denmark and the EU.

If the military were to comply with an order from Trump to seize Greenland, something widely regarded as illegal in the US, then it would be extremely dubious whether the US were not simply an autocratic regime, and the military might comply with an order to arrest Congress.

The internal mechanisms with the US seem to highlight the dynamics of the Democratic Peace Theory, as the most pro-democratic factions are the most pro-democratic in both domestic and in foreign policy.

So perhaps what has been called into question is not the hypothetical peacefulness of a world of democracies, but its sustainability, especially with libertarian free speech laws in the age of social media and growing misinformation and disinformation.

If this happened in the foundational liberal democracy on Earth, then perhaps this is indeed the future of most democracies, until there is a significant course-correction away from the more extreme interpretations of what democratic freedom must entail.

@threadreaderapp unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh