Today in United States History, February 15, 1798, a Congressman walked onto the House floor and beat his rival with a hickory cane. His opponent fought back with red-hot fire tongs. This really happened.

🧵 1/8

🧵 1/8

The setting was Congress Hall in Philadelphia, winter 1798. The young American republic, barely a decade old, was tearing itself apart. The infant nation faced an undeclared naval war with France, a Quasi-War that sent American ships to the bottom of the Atlantic and turned the political arena into a powder keg of fury and paranoia. Inside the elegant chambers where the Founders had imagined reasoned debate, a different reality was taking shape. The House of Representatives had become a battlefield where two emerging political factions: Federalists and Democratic-Republicans, weren't just disagreeing, they were at each other's throats... literally.

This was a world where honor meant everything and insult meant war. Politicians were expected to be gentlemen, hypersensitive to their reputations, willing to defend their dignity with violence if necessary. The code of honor that governed early American politics made every slight a potential death sentence, every debate a challenge to one's very manhood. Formal political parties hadn't fully formed yet, but the factions were already hardening into tribal warfare. President John Adams, a Federalist, pushed for military buildup against France. His opponents saw tyranny. His supporters saw treason. And in this toxic atmosphere, two men, Representative Roger Griswold of Connecticut and Representative Matthew Lyon of Vermont, were about to make history in the most violent way imaginable.

But the seeds of the February 15 explosion had been planted weeks earlier, in an exchange so shocking that it scandalized a nation still trying to figure out what democracy actually looked like.

🧵 2/8

This was a world where honor meant everything and insult meant war. Politicians were expected to be gentlemen, hypersensitive to their reputations, willing to defend their dignity with violence if necessary. The code of honor that governed early American politics made every slight a potential death sentence, every debate a challenge to one's very manhood. Formal political parties hadn't fully formed yet, but the factions were already hardening into tribal warfare. President John Adams, a Federalist, pushed for military buildup against France. His opponents saw tyranny. His supporters saw treason. And in this toxic atmosphere, two men, Representative Roger Griswold of Connecticut and Representative Matthew Lyon of Vermont, were about to make history in the most violent way imaginable.

But the seeds of the February 15 explosion had been planted weeks earlier, in an exchange so shocking that it scandalized a nation still trying to figure out what democracy actually looked like.

🧵 2/8

January 30, 1798. The House had just finished voting on whether to expel Senator William Blount from Tennessee. As representatives milled about the chamber in informal conversation, Matthew Lyon, a scrappy Irish immigrant who'd arrived in America as an indentured servant, was holding forth to a group of colleagues. Lyon, a Democratic-Republican who saw himself as champion of the common man, was tearing into Connecticut politicians. He accused them of corruption, of pursuing "their own private views" while ignoring "nine-tenths of their constituents." If he had a printing press in Connecticut, Lyon boasted, he could start a revolution there in six months.

Roger Griswold was listening. And Griswold was everything Lyon was not. Son of a Connecticut governor, grandson of a colonial governor, Yale-educated at fourteen, Griswold came from the upper echelon of New England's Federalist aristocracy. He was refined, brilliant, destined for greatness. And now this Irish upstart was insulting his home state, his class, his very identity. From across the room, Griswold called out: Would Lyon march into Connecticut with his wooden sword? It was a calculated strike designed to humiliate. Years earlier, Lyon had been temporarily and dishonorably discharged from the Continental Army under Horatio Gates, his political enemies claimed he'd been forced to wear a wooden sword as punishment for cowardice. The accusation was disputed, but the shame stuck to him like tar.

Lyon either didn't hear or chose to ignore the insult. So Griswold walked over, placed his hand on Lyon's arm, and repeated the question directly to his face. Lyon, insulted and embarrassed before his fellow Representatives, did something that shocked even this rough-and-tumble Congress. He spat tobacco juice directly into Griswold's face. Brown spittle ran down the Federalist's cheek. The chamber went silent. Griswold, without a word, calmly wiped his face with a handkerchief and walked out of the room. But everyone knew: this wasn't over.

🧵 3/8

Roger Griswold was listening. And Griswold was everything Lyon was not. Son of a Connecticut governor, grandson of a colonial governor, Yale-educated at fourteen, Griswold came from the upper echelon of New England's Federalist aristocracy. He was refined, brilliant, destined for greatness. And now this Irish upstart was insulting his home state, his class, his very identity. From across the room, Griswold called out: Would Lyon march into Connecticut with his wooden sword? It was a calculated strike designed to humiliate. Years earlier, Lyon had been temporarily and dishonorably discharged from the Continental Army under Horatio Gates, his political enemies claimed he'd been forced to wear a wooden sword as punishment for cowardice. The accusation was disputed, but the shame stuck to him like tar.

Lyon either didn't hear or chose to ignore the insult. So Griswold walked over, placed his hand on Lyon's arm, and repeated the question directly to his face. Lyon, insulted and embarrassed before his fellow Representatives, did something that shocked even this rough-and-tumble Congress. He spat tobacco juice directly into Griswold's face. Brown spittle ran down the Federalist's cheek. The chamber went silent. Griswold, without a word, calmly wiped his face with a handkerchief and walked out of the room. But everyone knew: this wasn't over.

🧵 3/8

The Federalists were outraged. An Irishman, a former indentured servant who sold himself for passage to America, had committed an act of "gross indecency" against one of their own. One Massachusetts Federalist called Lyon "a kennel of filth" who should be expelled immediately. Another branded him "a nasty, brutish, spitting animal." The phrase that captured Federalist fury: one member said he felt "grieved that the saliva of an Irishman should be left upon the face of an American." The xenophobia was naked and vicious. This wasn't just about spitting. It was about class, about ethnicity, about who deserved to be in the halls of power.

The Committee of Privileges drew up a formal resolution calling for Lyon's expulsion for violent attack and gross indecency. For two weeks, Congress debated. Republicans defended Lyon, arguing he'd been provoked by an unbearable insult to his military honor. Lyon himself wrote that he had no choice: if he'd said nothing, Federalist newspapers would have painted him as a "mean poltroon," a coward. The debate revealed the partisan chasm opening in American politics. Every speech, every vote became a proxy war for competing visions of the republic.

On February 14, the vote came. The chamber was electric with tension. To expel Lyon required a two-thirds majority. When the tally was announced, 73 to 21 against expulsion, the Federalists had failed. The vote fell strictly along party lines. Lyon would remain in Congress. But Roger Griswold was livid. The House had refused to defend his honor, refused to punish the man who'd humiliated him. Under the code that governed gentlemen's behavior, Griswold now had no choice. If the institution wouldn't give him satisfaction, he would take it himself. That night, Roger Griswold made a decision. Tomorrow, he would bring his hickory walking stick to the House floor. And tomorrow, Matthew Lyon would pay.

🧵 4/8

The Committee of Privileges drew up a formal resolution calling for Lyon's expulsion for violent attack and gross indecency. For two weeks, Congress debated. Republicans defended Lyon, arguing he'd been provoked by an unbearable insult to his military honor. Lyon himself wrote that he had no choice: if he'd said nothing, Federalist newspapers would have painted him as a "mean poltroon," a coward. The debate revealed the partisan chasm opening in American politics. Every speech, every vote became a proxy war for competing visions of the republic.

On February 14, the vote came. The chamber was electric with tension. To expel Lyon required a two-thirds majority. When the tally was announced, 73 to 21 against expulsion, the Federalists had failed. The vote fell strictly along party lines. Lyon would remain in Congress. But Roger Griswold was livid. The House had refused to defend his honor, refused to punish the man who'd humiliated him. Under the code that governed gentlemen's behavior, Griswold now had no choice. If the institution wouldn't give him satisfaction, he would take it himself. That night, Roger Griswold made a decision. Tomorrow, he would bring his hickory walking stick to the House floor. And tomorrow, Matthew Lyon would pay.

🧵 4/8

February 15, 1798. Morning light filtered through the windows of Congress Hall. Representatives gathered for another day of legislative business. Matthew Lyon sat at his desk, distracted, going through his mail. He didn't see Roger Griswold approaching. Didn't see the thick hickory walking stick in his hand. Then suddenly—crack!—Griswold struck Lyon across the head. Again. And again. "Scoundrel!" Griswold shouted, raining blows on Lyon's head and shoulders with savage fury.

One witness described the scene: "I was suddenly, and unsuspectedly interrupted by the sound of a violent blow I raised my head, and directly before me stood Mr. Griswold laying on blows with all his might upon Mr. Lyon." Lyon tried to grab his own cane but failed. He raised his arms to protect his head and face as Griswold continued the assault, striking him on the head, shoulders, and arms. Lyon pressed toward Griswold, trying to close with him and fight back with his fists, but Griswold fell back, maintaining distance, continuing his methodical beating. The aristocrat was winning.

Then Lyon turned and made for the fireplace. He seized the fire tongs, heavy iron implements used to arrange burning logs. They were still warm from the morning fire. Lyon wheeled around, tongs raised high like a medieval mace, and charged at Griswold. Now it was the Federalist's turn to defend. Griswold dropped his stick and seized the tongs with one hand and Lyon's collar with the other. The two men struggled, locked together in mortal combat on the floor of the United States House of Representatives. Other members formed a ring around them, watching, not intervening. Some accounts suggest they were entertained by the "royal sport." Then Griswold tripped Lyon and threw him to the floor, landing one or two blows to his face. Finally, only then, did other congressmen rush forward to pull them apart, several grabbing Griswold by his legs to pry him off Lyon. When they were separated, both men were bloodied, panting, and unrepentant. The floor of Congress was now literally a battlefield.

🧵 5/8

One witness described the scene: "I was suddenly, and unsuspectedly interrupted by the sound of a violent blow I raised my head, and directly before me stood Mr. Griswold laying on blows with all his might upon Mr. Lyon." Lyon tried to grab his own cane but failed. He raised his arms to protect his head and face as Griswold continued the assault, striking him on the head, shoulders, and arms. Lyon pressed toward Griswold, trying to close with him and fight back with his fists, but Griswold fell back, maintaining distance, continuing his methodical beating. The aristocrat was winning.

Then Lyon turned and made for the fireplace. He seized the fire tongs, heavy iron implements used to arrange burning logs. They were still warm from the morning fire. Lyon wheeled around, tongs raised high like a medieval mace, and charged at Griswold. Now it was the Federalist's turn to defend. Griswold dropped his stick and seized the tongs with one hand and Lyon's collar with the other. The two men struggled, locked together in mortal combat on the floor of the United States House of Representatives. Other members formed a ring around them, watching, not intervening. Some accounts suggest they were entertained by the "royal sport." Then Griswold tripped Lyon and threw him to the floor, landing one or two blows to his face. Finally, only then, did other congressmen rush forward to pull them apart, several grabbing Griswold by his legs to pry him off Lyon. When they were separated, both men were bloodied, panting, and unrepentant. The floor of Congress was now literally a battlefield.

🧵 5/8

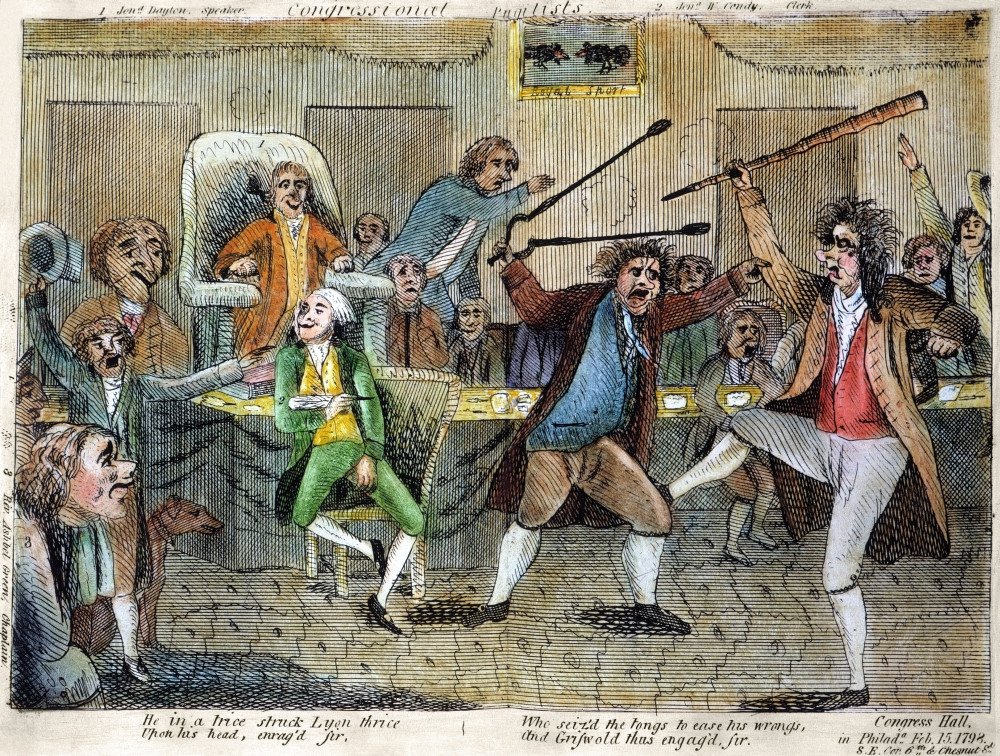

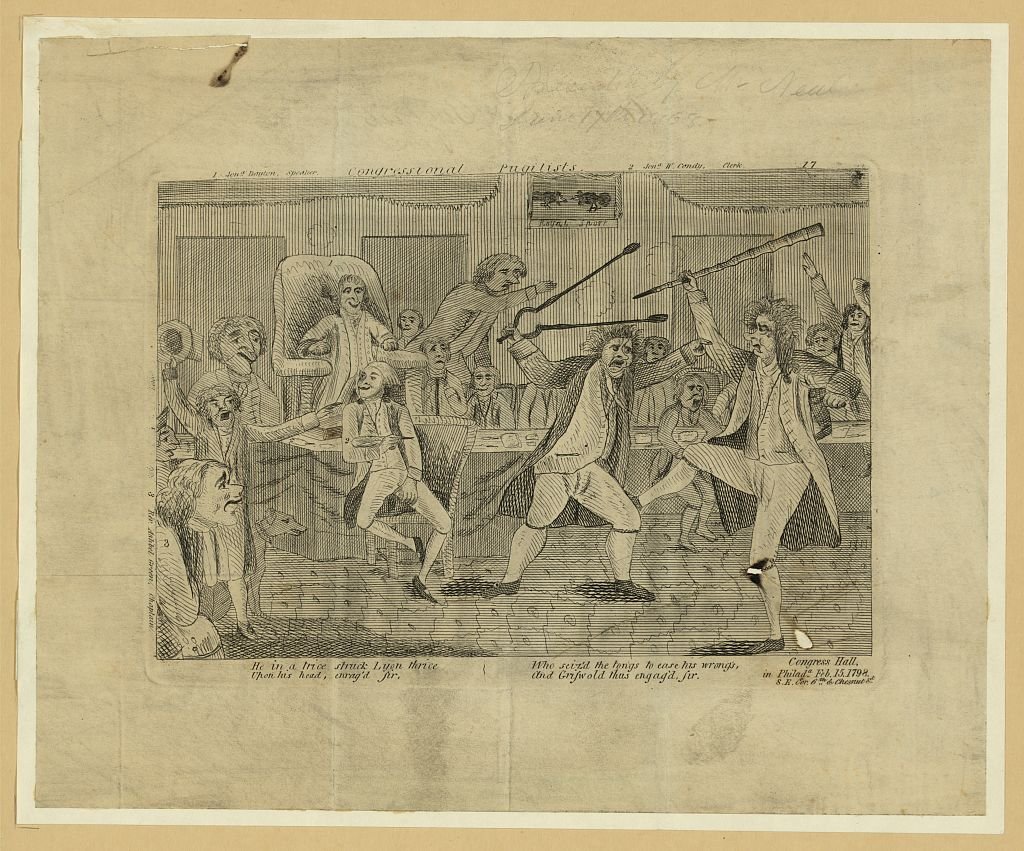

The aftermath was immediate and chaotic. A committee was appointed to investigate. Should both men be expelled? Censured? The cartoonists got to work immediately, the most famous image, "Congressional Pugilists" showed Griswold with his cane and Lyon with his tongs, locked in combat while Speaker Jonathan Dayton and other members looked on. Below the illustration ran satirical verses: "He in a trice struck Lyon thrice / Upon his head, enrag'd sir, / Who seiz'd the tongs to ease his wrongs, / And Griswold thus engag'd, sir." The cartoon became one of the first viral political images in American history, spreading through newspapers and print shops from Boston to Charleston.

The House held another vote: should both men be expelled for bringing violence to the chamber? The committee recommended censure. But again, partisan politics ruled. On the vote to expel both combatants, the measure failed 73 to 21, the exact same vote as before. Neither Federalists nor Republicans would sacrifice their own fighter. The issue was finally resolved only when both Lyon and Griswold stood before the House and promised to keep the peace and remain on good behavior. It was a gentleman's agreement between two men who'd just beaten each other bloody.

The national reaction revealed a country already fractured. Federalist newspapers portrayed Griswold as a gentleman defending his honor against an Irish brute. Republican papers cast Lyon as a scrappy champion of the people standing up to aristocratic bullies. One friend wrote to a political ally: "Griswold, I trust, he will take personal vengeance when his hands are untied, Vengeance is called for everywhere among the sound part of society." The violence on the House floor wasn't an aberration. It was a symptom of something much deeper and more dangerous: America was coming apart at the seams. The partisan hatred, the us-versus-them tribalism, the sense that the other side wasn't just wrong but illegitimate, all of it was metastasizing into something that threatened the entire democratic experiment. And it was about to get worse.

🧵 6/8

The House held another vote: should both men be expelled for bringing violence to the chamber? The committee recommended censure. But again, partisan politics ruled. On the vote to expel both combatants, the measure failed 73 to 21, the exact same vote as before. Neither Federalists nor Republicans would sacrifice their own fighter. The issue was finally resolved only when both Lyon and Griswold stood before the House and promised to keep the peace and remain on good behavior. It was a gentleman's agreement between two men who'd just beaten each other bloody.

The national reaction revealed a country already fractured. Federalist newspapers portrayed Griswold as a gentleman defending his honor against an Irish brute. Republican papers cast Lyon as a scrappy champion of the people standing up to aristocratic bullies. One friend wrote to a political ally: "Griswold, I trust, he will take personal vengeance when his hands are untied, Vengeance is called for everywhere among the sound part of society." The violence on the House floor wasn't an aberration. It was a symptom of something much deeper and more dangerous: America was coming apart at the seams. The partisan hatred, the us-versus-them tribalism, the sense that the other side wasn't just wrong but illegitimate, all of it was metastasizing into something that threatened the entire democratic experiment. And it was about to get worse.

🧵 6/8

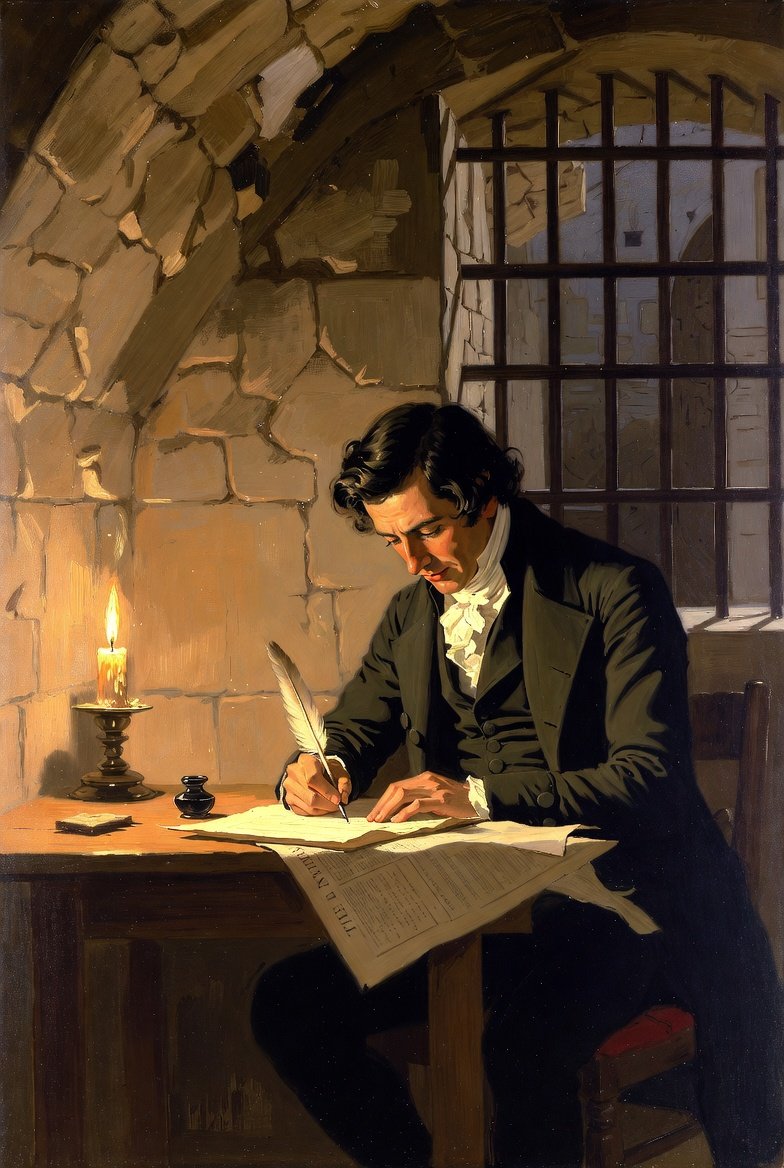

Matthew Lyon's story didn't end with the brawl. Later that year, President John Adams signed the Alien and Sedition Acts into law, legislation that made it a federal crime to criticize the president or government. Lyon, who'd been writing inflammatory articles in his own newspaper, became target number one. In October 1798, he was arrested for accusing Adams of "an unbounded thirst for ridiculous pomp." Lyon became the first person prosecuted under the Sedition Act. At his trial, he argued the law was unconstitutional, a violation of the First Amendment. The judge, Supreme Court Justice William Paterson sitting as circuit judge, rejected his defense. Lyon was convicted and sentenced to four months in jail and a $1,000 fine.

The Federalists expected Lyon to be finished, his political career destroyed. Instead, something extraordinary happened. From his jail cell in Vergennes, Vermont, where he was held in a common cell with criminals while one of his own judges who'd been imprisoned for debt got a private room, Lyon ran for reelection to Congress. And won. In a landslide. Vermont voters returned him to office with nearly twice the votes of his nearest rival. He became the first and only person ever elected to Congress while in prison. The Green Mountain Boys threatened to tear down the jail to free him, but Lyon urged restraint. When he was finally released in early 1801, he returned to Congress to a hero's welcome among Republicans.

And in that moment, Matthew Lyon got his ultimate revenge. The presidential election of 1800 between Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr had ended in an Electoral College tie, throwing the decision to the House of Representatives. As Vermont's representative, Lyon cast the deciding vote: for Thomas Jefferson. The man whom Federalists had branded a filthy Irishman, the man who'd fought with fire tongs on the House floor, the man who'd been imprisoned for sedition, cast the vote that made Thomas Jefferson the third President of the United States and ended the Federalist stranglehold on power. Roger Griswold went on to become Governor of Connecticut but died in 1812. The Sedition Act was later declared unconstitutional, and Lyon's fine was eventually remitted to his heirs. But the real legacy was just beginning.

🧵 7/8

The Federalists expected Lyon to be finished, his political career destroyed. Instead, something extraordinary happened. From his jail cell in Vergennes, Vermont, where he was held in a common cell with criminals while one of his own judges who'd been imprisoned for debt got a private room, Lyon ran for reelection to Congress. And won. In a landslide. Vermont voters returned him to office with nearly twice the votes of his nearest rival. He became the first and only person ever elected to Congress while in prison. The Green Mountain Boys threatened to tear down the jail to free him, but Lyon urged restraint. When he was finally released in early 1801, he returned to Congress to a hero's welcome among Republicans.

And in that moment, Matthew Lyon got his ultimate revenge. The presidential election of 1800 between Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr had ended in an Electoral College tie, throwing the decision to the House of Representatives. As Vermont's representative, Lyon cast the deciding vote: for Thomas Jefferson. The man whom Federalists had branded a filthy Irishman, the man who'd fought with fire tongs on the House floor, the man who'd been imprisoned for sedition, cast the vote that made Thomas Jefferson the third President of the United States and ended the Federalist stranglehold on power. Roger Griswold went on to become Governor of Connecticut but died in 1812. The Sedition Act was later declared unconstitutional, and Lyon's fine was eventually remitted to his heirs. But the real legacy was just beginning.

🧵 7/8

The Lyon-Griswold brawl was a warning shot that America didn't fully heed. It revealed a truth that still haunts us: when partisan hatred becomes total, when the other side isn't just opponents but enemies, when honor culture and tribal loyalty override institutional norms, democracy itself becomes a cage match. The "Congressional Pugilists" cartoon wasn't just satire, it was prophecy. The violence that exploded on February 15, 1798 was just the beginning of a pattern that would define American politics for the next six decades, culminating in Senator Charles Sumner being beaten nearly to death with a cane on the Senate floor in 1856, and eventually, in the Civil War itself.

What made the 1798 brawl different from schoolyard violence or barroom fights was its location and meaning. This happened in the sacred space where democracy was supposed to work: where words, not weapons, were meant to settle disputes. When representatives of the people resort to clubs and fire tongs, the message is clear: the system has failed. Reason has lost. The fact that Congress refused to punish either man, voting strictly along party lines, made it even worse. The institution itself had become so partisan that it couldn't even defend its own dignity.

Today, we like to think we're more civilized. We don't beat each other with canes on the House floor (though there have been close calls). But the underlying pathology: the partisan tribalism, the politics of personal destruction, the sense that the other side is not just wrong but illegitimate... all of that remains. Lyon and Griswold fought with fire tongs and hickory sticks. We fight with social media mobs and cable news demonization. The weapons have changed. The rage hasn't. On February 15, 1798, two congressmen turned the House floor into a battleground. They showed us what American democracy looks like when honor matters more than governance, when pride matters more than country, when winning the fight matters more than preserving the arena where the fight takes place. It's a lesson we're still learning.

🧵 8/8

What made the 1798 brawl different from schoolyard violence or barroom fights was its location and meaning. This happened in the sacred space where democracy was supposed to work: where words, not weapons, were meant to settle disputes. When representatives of the people resort to clubs and fire tongs, the message is clear: the system has failed. Reason has lost. The fact that Congress refused to punish either man, voting strictly along party lines, made it even worse. The institution itself had become so partisan that it couldn't even defend its own dignity.

Today, we like to think we're more civilized. We don't beat each other with canes on the House floor (though there have been close calls). But the underlying pathology: the partisan tribalism, the politics of personal destruction, the sense that the other side is not just wrong but illegitimate... all of that remains. Lyon and Griswold fought with fire tongs and hickory sticks. We fight with social media mobs and cable news demonization. The weapons have changed. The rage hasn't. On February 15, 1798, two congressmen turned the House floor into a battleground. They showed us what American democracy looks like when honor matters more than governance, when pride matters more than country, when winning the fight matters more than preserving the arena where the fight takes place. It's a lesson we're still learning.

🧵 8/8

@threadreaderapp unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh