One of the stranger assumptions of the Brexit debate was that we live in an age of permanently low tariffs, guaranteed by a liberal world trading order. It’s indicative of a wider problem in UK politics: the near-total absence of historical & prudential considerations. [1/12]

External Tweet loading...

If nothing shows, it may have been deleted

by @BBCBreaking view original on Twitter

When Britain joined the EEC, in 1973, the world looked very different. A liberal trading order based on the Bretton Woods System had collapsed. The world seemed to be breaking up into hostile trading blocs, which, like OPEC, could use their power to devastating effect. [2/12]

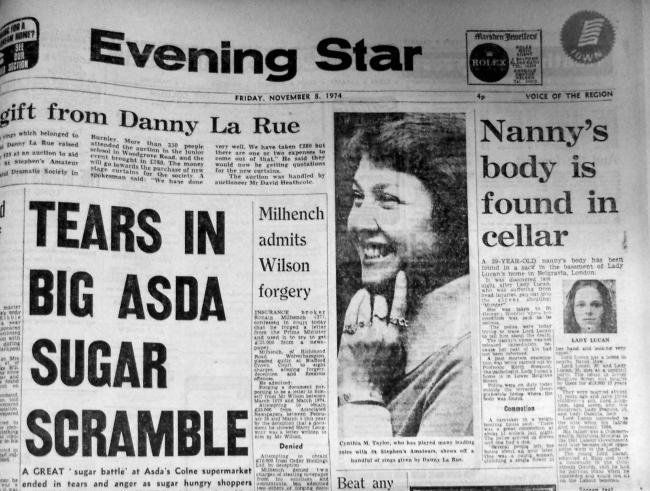

There was serious anxiety in government about food shortages: British shops ran out of sugar in 1974 and there were queues outside bakeries in London. Newspapers debated a return to the ration book. [3/12]

Europe seemed dangerously exposed to Russian power, with the United States retreating into introspection after the horrors of Vietnam and the internal convulsions over Watergate. Harold Wilson told the Cabinet in 1974 that “American leadership had gone”. [4/12]

Joining the EEC was a response to all three. It bound Britain into a trade bloc that could stand its ground against the superpowers. It gave Britain preferential access to European food supplies & encouraged domestic production. It provided an economic foundation for NATO. [5/12]

By the 90s, when modern Euroscepticism was incubating, the world had changed. The collapse of the Soviet bloc, the lowering of tariff barriers & abundant food supplies weakened the case for membership as it had been made in the 1970s – and pro-Europeans failed to respond. [6/12]

But what if those conditions returned? What if trade wars became the new norm? What if cheap food became harder to access, for political, economic or climatic reasons? What if a resurgent Russia threatened Europe's security? That world seems less alien now than 2 years ago.[7/12]

History only really teaches one lesson: that the world we live in is contingent, not fixed; that things we take for granted in the present have been different in the past – and will be different again in the future. [8/12]

States have to balance the needs of the present against future contingencies. The armed forces maintain in times of peace weapons that would only be necessary in the most apocalyptic of wars. We are less good at building contingency into our political and economic thought. [9/12]

This role used to be played by "conservatism", injecting the political system with a scepticism of precipitate change to institutions inherited from the past. Yet one of the strangest features of modern British politics is the “strange death of conservatism” on the Right. [10/12]

The Conservative Party today is not in any meaningful sense “conservative”: its thinking is almost entirely ahistorical, grounded in a universalist creed of marketization that must be applied to all institutions, relationships and organs of civil society. [11/12]

Ironically, that means it struggles to adapt to “change”, because a contingent world of liberal markets & global trading rules is assumed to be the universal state of humanity. These are not Thatcher’s children; they’re Francis Fukayama’s. We may all be poorer as a result. [END]

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh