With the upcoming Neil-Gaiman-orchestrated "Dreaming" line at DC comics, I thought it might be time to revisit Neil Gaiman's wonderful "Sandman."

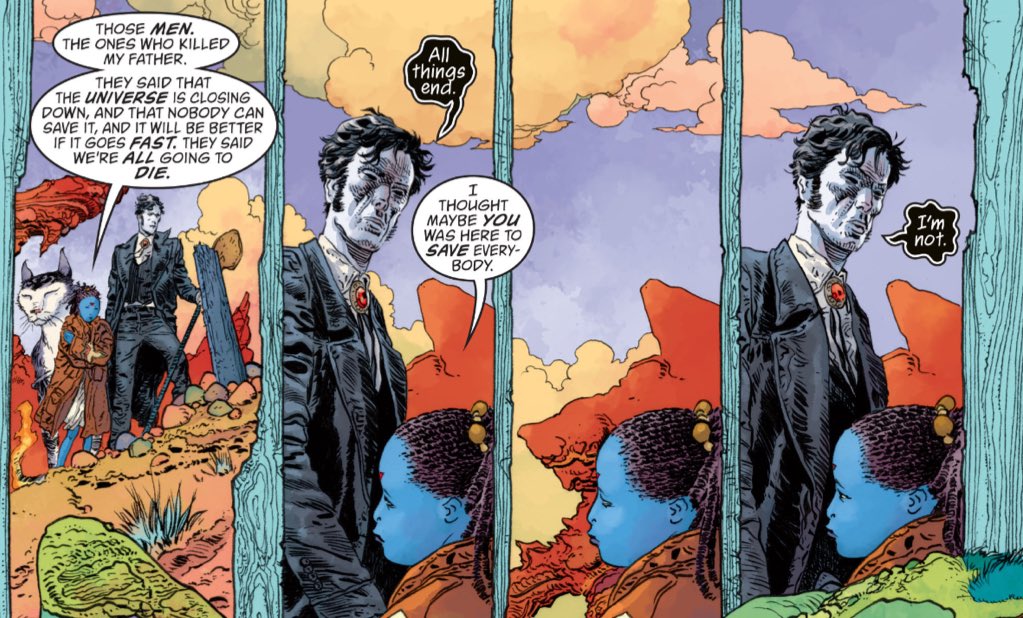

(Sandman: Overture #1.)

(Sandman: Overture #1.)

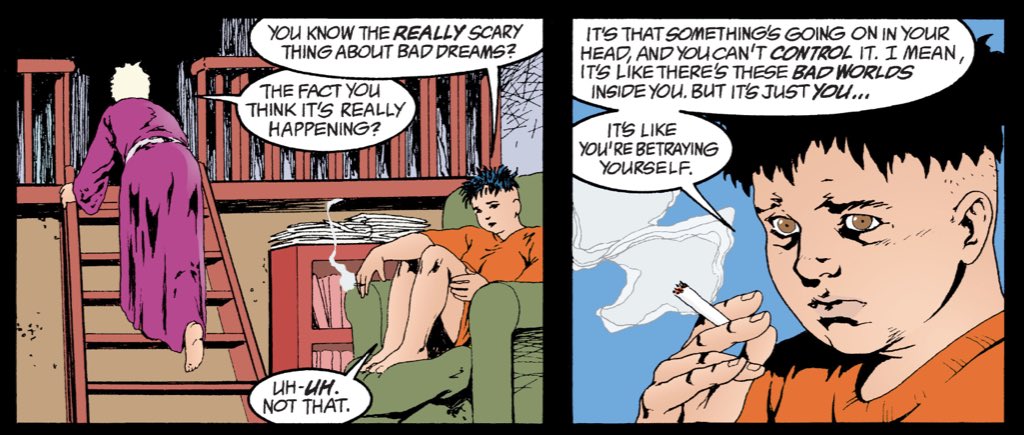

It's funny, I was just thinking today about the late sixties paranoia about cultural psychosis and insanity.

Modern pop culture is similarly fixated on the idea of insanity rippling through the popular unconscious.

"Legion", "Westworld", etc.

(Sandman: Overture #2.)

Modern pop culture is similarly fixated on the idea of insanity rippling through the popular unconscious.

"Legion", "Westworld", etc.

(Sandman: Overture #2.)

It's almost surprising that it took as long as it did for Gaiman to write for "Doctor Who."

Gaiman's abstract/symbolic cosmos is very much in keeping with Russell T. Davies' approach to concepts like "the Time War."

(Sandman: Overture #2.)

Gaiman's abstract/symbolic cosmos is very much in keeping with Russell T. Davies' approach to concepts like "the Time War."

(Sandman: Overture #2.)

I have a lot of memories of "Sandman", particularly of the people with whom I shared it as a teenager.

I have a few people of whom I still think fondly when I see "the Dream of Cats", the avatar of one of the series' best "just try it, please?" issues.

(Sandman: Overture #2.)

I have a few people of whom I still think fondly when I see "the Dream of Cats", the avatar of one of the series' best "just try it, please?" issues.

(Sandman: Overture #2.)

The past few years have been kind to the absurd stakes of things like comic books.

A decade ago, "the destruction of reality itself" seemed impossibly abstract, too much to fathom.

Today, audiences seem to be actually living through it.

(Sandman: Overture #3.)

A decade ago, "the destruction of reality itself" seemed impossibly abstract, too much to fathom.

Today, audiences seem to be actually living through it.

(Sandman: Overture #3.)

Interestingly, Gaiman roots the prequel elements of "Overture" in something akin to a comic book crisis.

Sandman launched in January 1989, only a few years after "Crisis on Infinite Earths."

Here: Mogo, a character of that era, does socialise.

(Sandman: Overture #3.)

Sandman launched in January 1989, only a few years after "Crisis on Infinite Earths."

Here: Mogo, a character of that era, does socialise.

(Sandman: Overture #3.)

The crisis is even implied to have drawn in characters from the Marvel Universe, and even previously-unseen characters from the imagination of Jack Kirby.

Does "Sandman: Overture" unfold against a metaphorical echo of the original "Crisis"? Or vice versa?

(Sandman: Overture #3)

Does "Sandman: Overture" unfold against a metaphorical echo of the original "Crisis"? Or vice versa?

(Sandman: Overture #3)

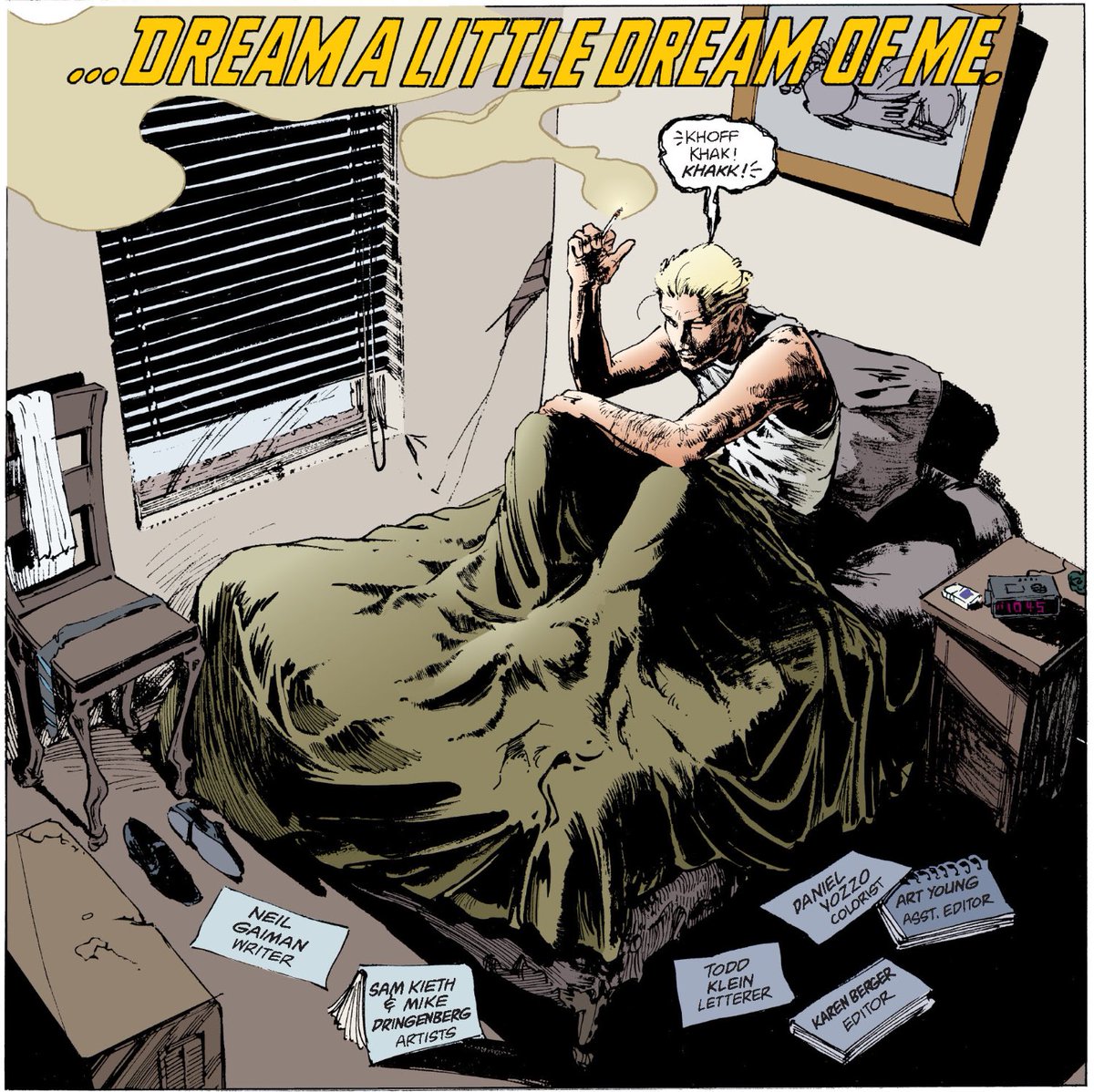

Feck it.

I've moved on to Gaiman's original "Sandman" run.

Still one of the most accessible runs in comic book history, and a great run to give to a newcomer.

It's part of what lured me to the medium. So expect nostalgia if this thread continues.

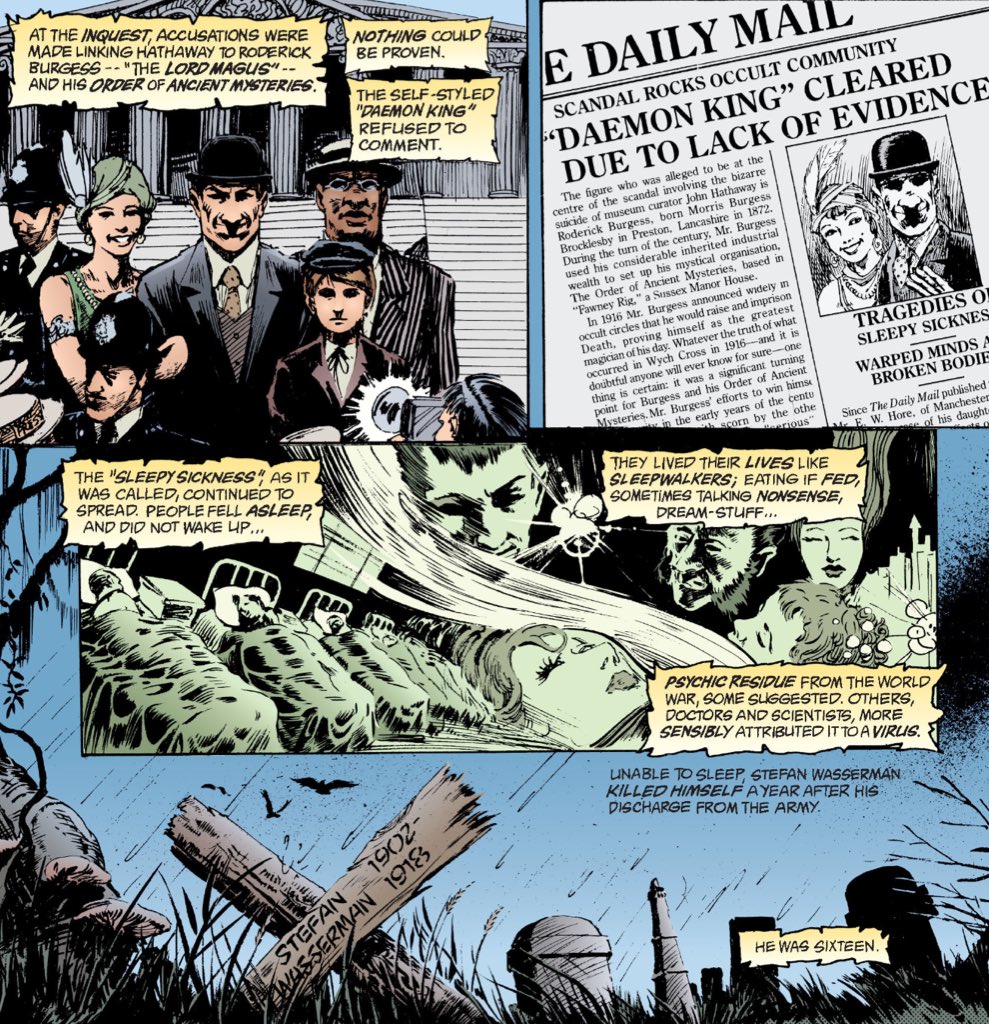

(Sandman #1.)

I've moved on to Gaiman's original "Sandman" run.

Still one of the most accessible runs in comic book history, and a great run to give to a newcomer.

It's part of what lured me to the medium. So expect nostalgia if this thread continues.

(Sandman #1.)

I should note that I tweet a lot about comic books, but only because I can't find the time to write at length about them.

I hope these threads aren't too distracting for non-comics people. But I do thread them so you can mute them if they get annoying.

(Sandman #1.)

I hope these threads aren't too distracting for non-comics people. But I do thread them so you can mute them if they get annoying.

(Sandman #1.)

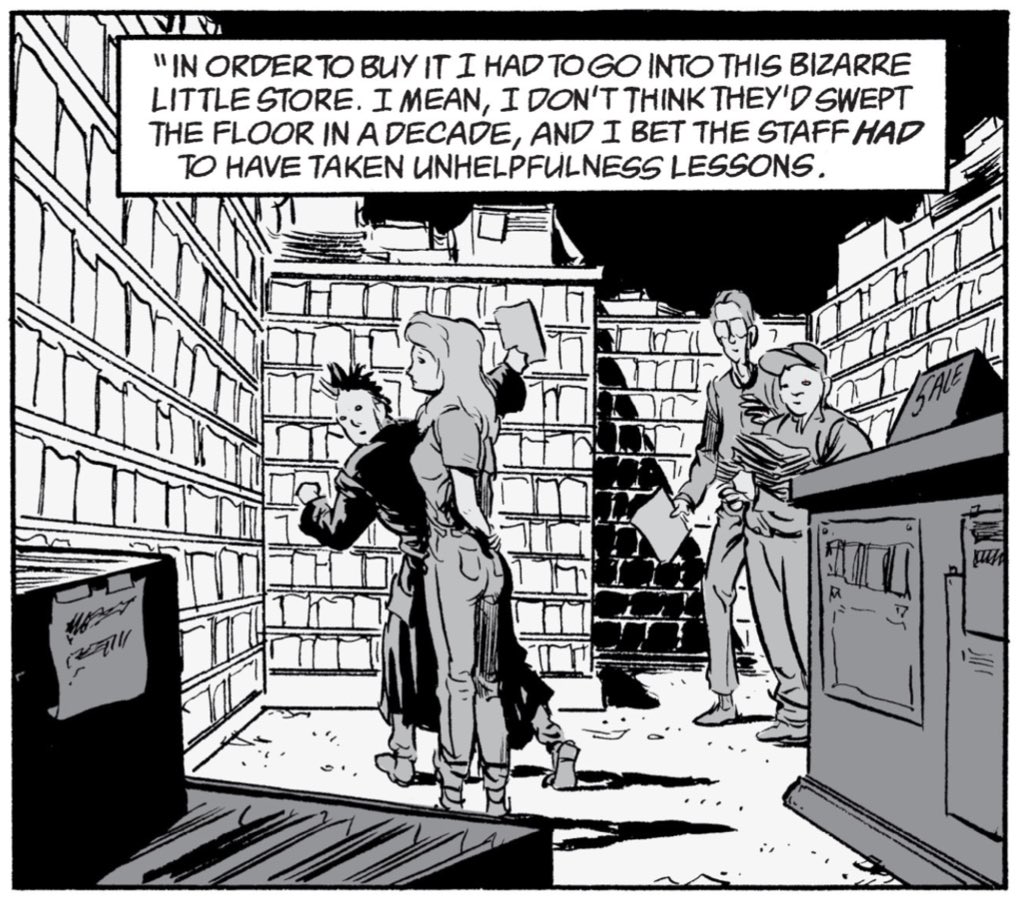

"Sandman" is one of the great "introduce people who don't like comic books to comic books" series.

In part, because it's a great showcase for the medium's storytelling potential, within a recognisable (albeit heightened) framework that isn't superheroes.

(Sandman #1.)

In part, because it's a great showcase for the medium's storytelling potential, within a recognisable (albeit heightened) framework that isn't superheroes.

(Sandman #1.)

Sure, there are plenty of accessible non-superhero books. Brubaker/Phillips' "Criminal", the Hernandez Brothers' "Love & Rockets", Kirkman's "Walking Dead."

But (a.) these were less common in 1989, and (b.) Sandman is still impossible to imagine in another medium.

(Sandman #1.)

But (a.) these were less common in 1989, and (b.) Sandman is still impossible to imagine in another medium.

(Sandman #1.)

There has, of course, been talk of adapting "Sandman", whether in film, series or animation.

But, as with "Watchmen", the comic is so tied to its medium that it's hard to imagine a direct and literal adaptation working.

And that's not a bad thing.

(Sandman #1.)

But, as with "Watchmen", the comic is so tied to its medium that it's hard to imagine a direct and literal adaptation working.

And that's not a bad thing.

(Sandman #1.)

“Sandman” still doesn’t get enough credit as a gateway to the medium for young female readers to the medium, at a time when it seemed openly hostile to them.

(It still kinda does. Here’s Gaiman himself on “Sandman” as a comic attracting female readers.)

npr.org/2015/12/15/458…

(It still kinda does. Here’s Gaiman himself on “Sandman” as a comic attracting female readers.)

npr.org/2015/12/15/458…

This enthusiastic female audience may explain why “Sandman” often struggles for the recognition it’s due in the comics canon, despite its measurable critical/commercial success.

Consider how “Sandman” fans are perceived. (Among internet comics fans!)

newyorker.com/magazine/2010/…

Consider how “Sandman” fans are perceived. (Among internet comics fans!)

newyorker.com/magazine/2010/…

Traditionally “masculine” fan spaces - often rooted in erasures of female fandom, but that’s a different debate - are hostile to intrusions by female fans even today.

I can imagine that the tensions thirty years ago weighed heavily on “Sandman.”

laweekly.com/arts/comic-con…

I can imagine that the tensions thirty years ago weighed heavily on “Sandman.”

laweekly.com/arts/comic-con…

All of which is nonsense, by the way.

“Sandman” is a classic. There’s a reason that it became a cornerstone of the Vertigo line, as editor Karen Berger outlines.

It’s one of the most influential and important conics ever published.

newsarama.com/4151-vertigo-s…

“Sandman” is a classic. There’s a reason that it became a cornerstone of the Vertigo line, as editor Karen Berger outlines.

It’s one of the most influential and important conics ever published.

newsarama.com/4151-vertigo-s…

One of the interesting tensions within "Sandman" is how the comic was rooted in the DC Universe, but quickly grew beyond it.

That relationship is fascinating, Dream as a force at work in the DCU, but also outside of it.

(Sandman #1.)

That relationship is fascinating, Dream as a force at work in the DCU, but also outside of it.

(Sandman #1.)

It admittedly takes Gaiman a good half-dozen issues to find his voice on "Sandman."

Part of this tonal, as he's clearly initially writing a horror comic, but it's also because he's writing a comic set in the DC Universe.

Neither of those is what "Sandman" is.

(Sandman #1.)

Part of this tonal, as he's clearly initially writing a horror comic, but it's also because he's writing a comic set in the DC Universe.

Neither of those is what "Sandman" is.

(Sandman #1.)

To be fair, I think Gaiman gets a better handle on the use of continuity later in his run, with the various "stand-in Sandmen" and the "Prez" issue.

But, by that point, he realises what he's doing is so much bigger than the DC Universe.

(Sandman #1.)

But, by that point, he realises what he's doing is so much bigger than the DC Universe.

(Sandman #1.)

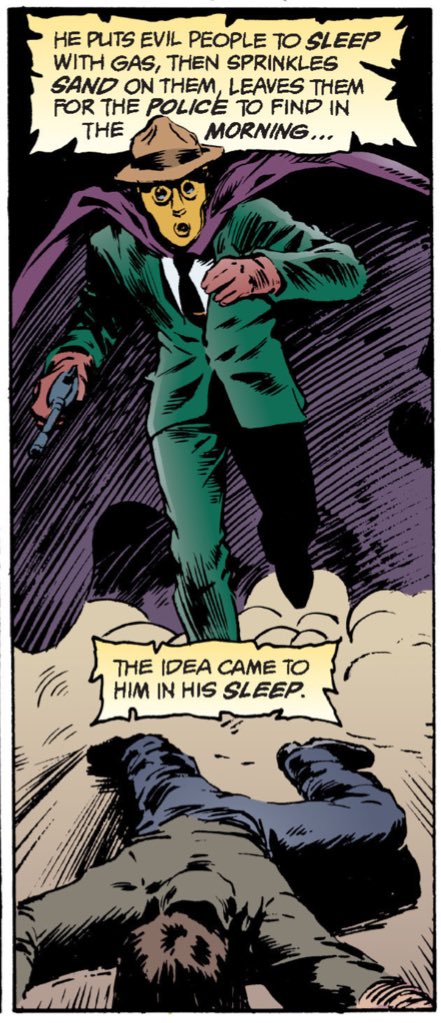

Reading the early issues of Neil Gaiman's "Sandman", it's clear how much he used Alan Moore's "Swamp Thing" as a springboard. Which makes sense.

That sense is enhanced by Adam Keith and Mike Dringenberg's artwork, which is very much "late eighties horror comic."

(Sandman #2.)

That sense is enhanced by Adam Keith and Mike Dringenberg's artwork, which is very much "late eighties horror comic."

(Sandman #2.)

It should be noted that even these flirtations with the DC Universe had a lasting impact.

Gaiman's characterisation of "Doctor Destiny" undoubtedly informed the presentation of him in "Arkham Asylum" and the DCAU.

He'd likely have faded into obscurity without it.

(Sandman #2.)

Gaiman's characterisation of "Doctor Destiny" undoubtedly informed the presentation of him in "Arkham Asylum" and the DCAU.

He'd likely have faded into obscurity without it.

(Sandman #2.)

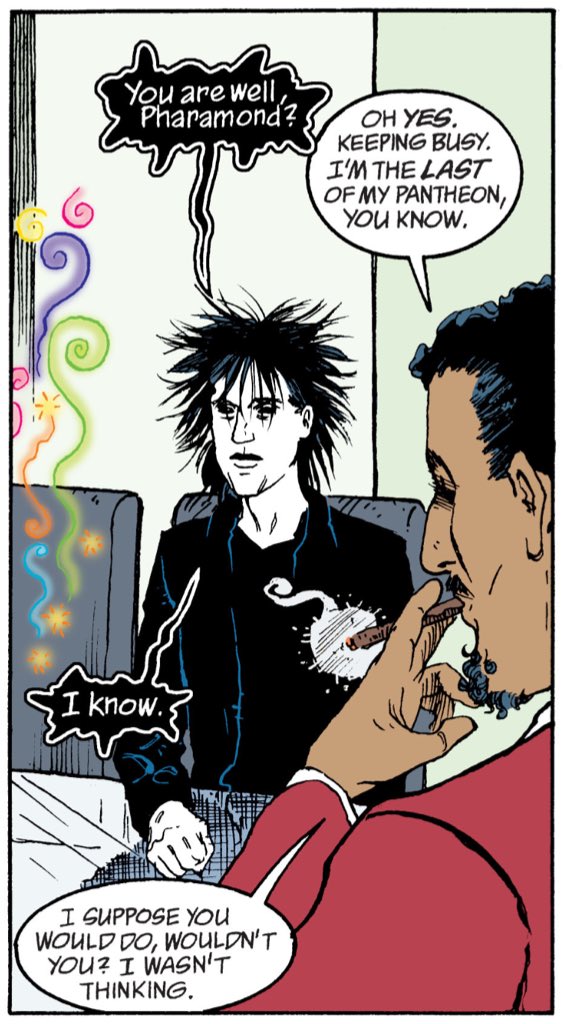

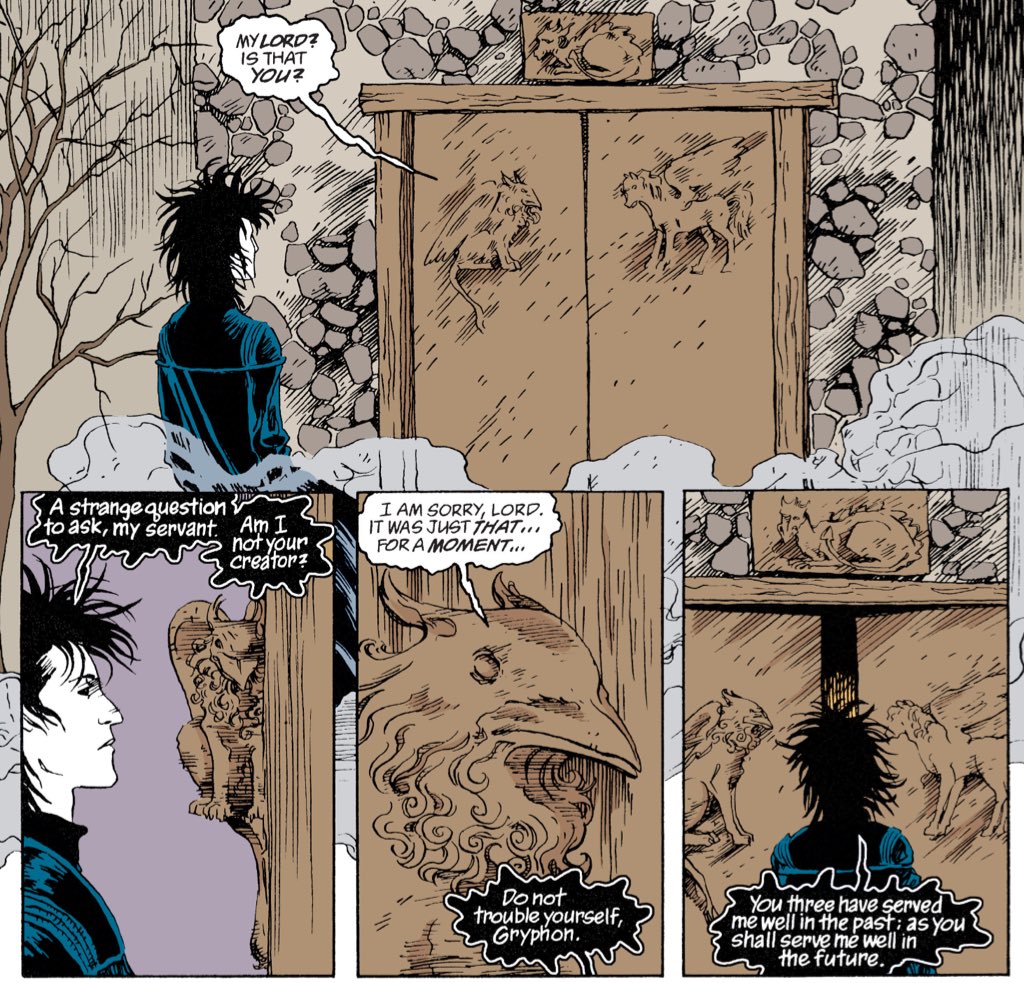

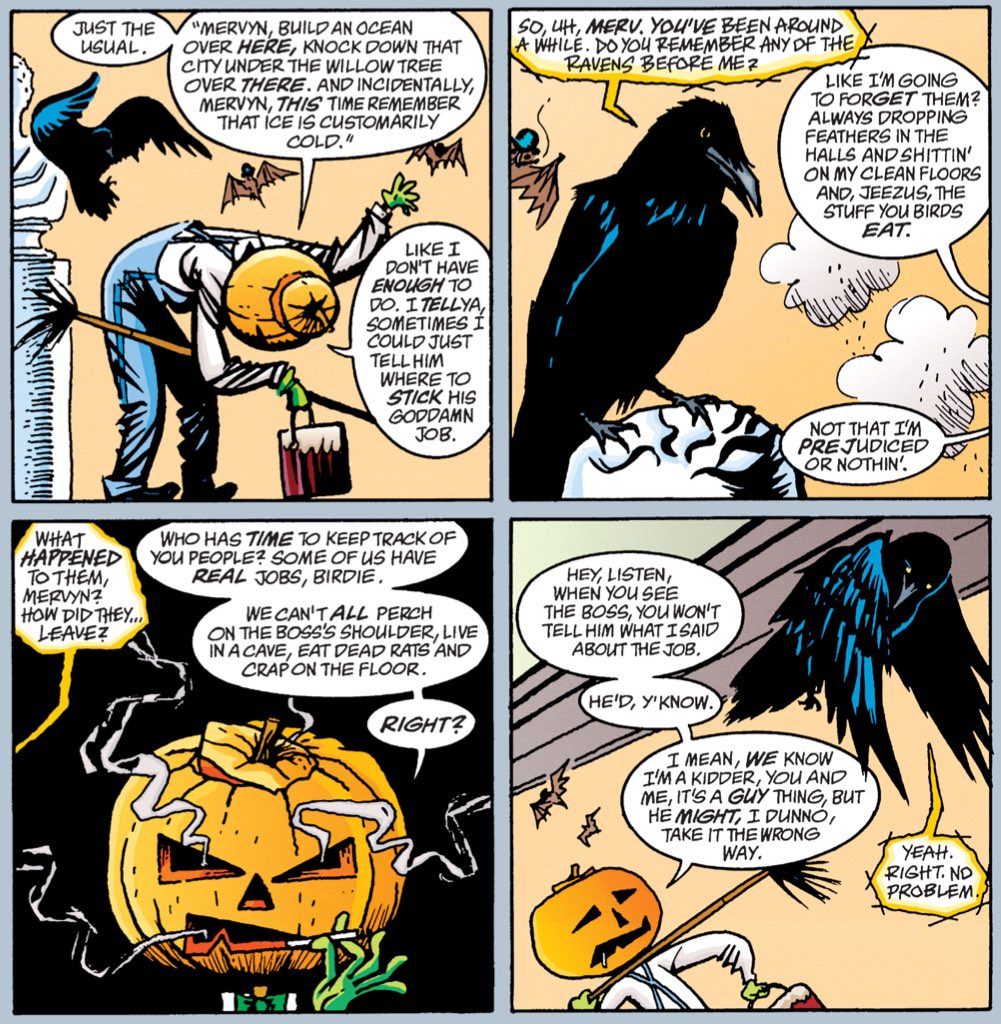

I'd forgotten how great Gaiman was at building fantastic worlds, which makes sense given his long association with Terry Pratchett.

Some of these details seed later stories. Some don't, but they all add to the sense of place in "Sandman."

(Sandman #2.)

Some of these details seed later stories. Some don't, but they all add to the sense of place in "Sandman."

(Sandman #2.)

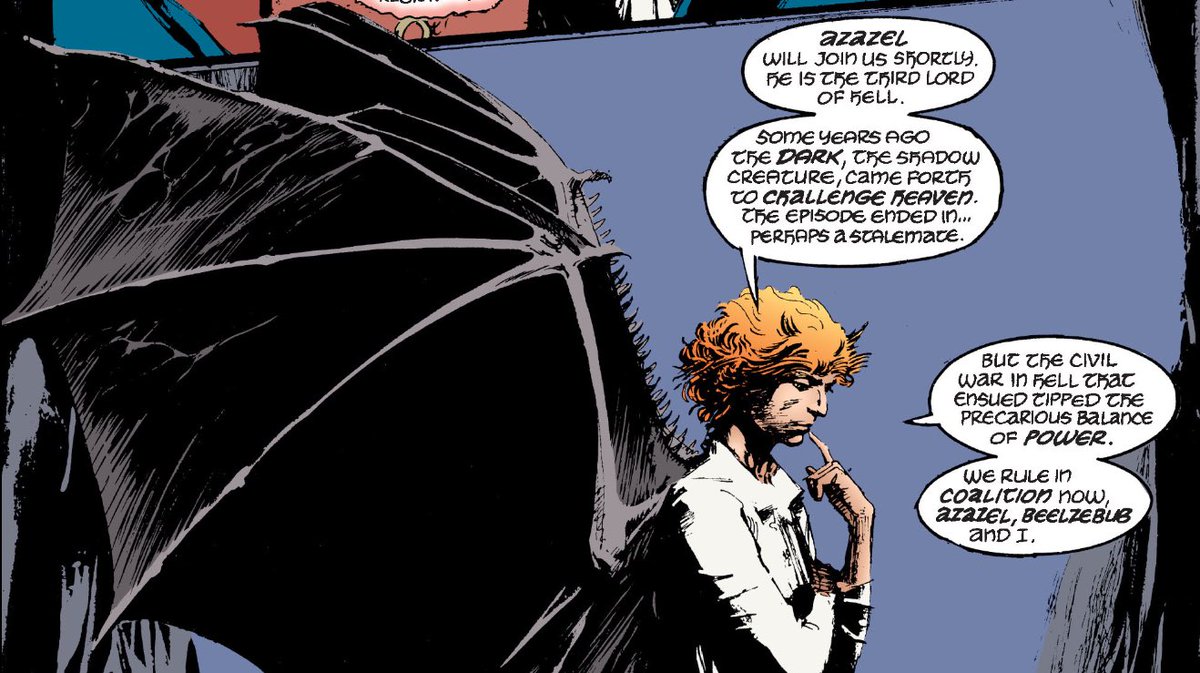

While it takes "Sandman" a little while to find its feet in the fairly conventional "item quest" introductory arc, Neil Gaiman sets up a lot of ideas that pay off down the line.

Such as his introduction of Lucifer's hatred of Morpheus.

(Sandman #4.)

Such as his introduction of Lucifer's hatred of Morpheus.

(Sandman #4.)

Lucifer who, by the way, bears an uncanny resemblance to a certain iconic British pop star.

(Sandman #4.)

(Sandman #4.)

DC flattened their publishing line with the "new 52" and "Flashpoint."

But there was something slightly transgressive in the way that the first arc of "Sandman" flit between the world of Vertigo and the DC Universe.

John Constantine and the Martian Manhunter.

(Sandman #3.)

But there was something slightly transgressive in the way that the first arc of "Sandman" flit between the world of Vertigo and the DC Universe.

John Constantine and the Martian Manhunter.

(Sandman #3.)

With a plot involving Constantine, Arkham Asylum, the "Swamp Thing" crisis crossover and even Lucifer, this first arc of "Sandman" feels like a Vertigo shared universe.

Years before Mike Carey awkwardly attempted the same thing during his "Hellblazer" run.

(Sandman #4.)

Years before Mike Carey awkwardly attempted the same thing during his "Hellblazer" run.

(Sandman #4.)

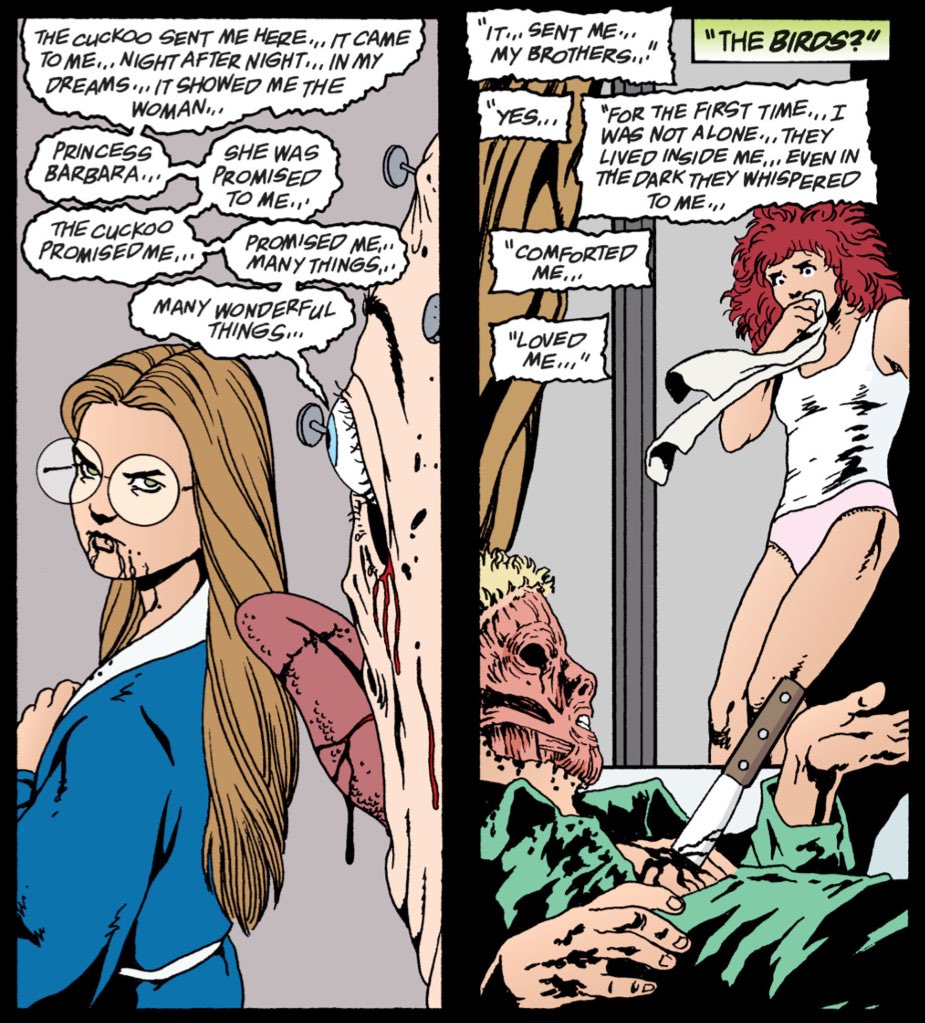

The first third or so of "Sandman" is much more horror-tinged than what follows, which can be a barrier to entry.

The Doctor Destiny stuff gave me nightmares as a kid, even more than the "Cereal Convention" stuff.

It's brutal, and vicious, and nasty.

(Sandman #5.)

The Doctor Destiny stuff gave me nightmares as a kid, even more than the "Cereal Convention" stuff.

It's brutal, and vicious, and nasty.

(Sandman #5.)

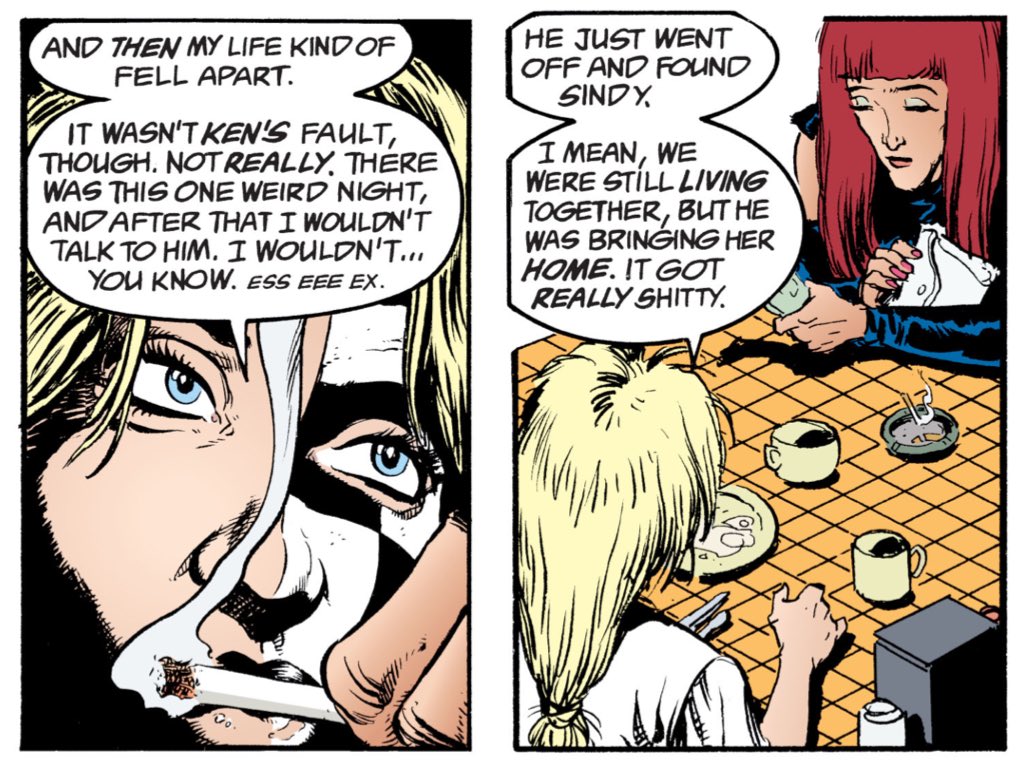

The sixth issue of Sandman is a tough read. It was when I first read it. It is even now, more than a decade later.

Of course, that means it's a very good horror comic. It may be the best horror comic I have ever read, give or take "From Hell."

(Sandman #6.)

Of course, that means it's a very good horror comic. It may be the best horror comic I have ever read, give or take "From Hell."

(Sandman #6.)

Part of what makes the sixth issue so effective is that Neil Gaiman effectively weaponises his skill at guiding the audience's empathy and compassion.

He makes these characters feel real, in their details and imperfections. Before tearing them apart.

(Sandman #6.)

He makes these characters feel real, in their details and imperfections. Before tearing them apart.

(Sandman #6.)

Gaiman is as a empathic a writer as anyone. I have never doubted that Gaiman loves people, across the length and breadth of his career.

But in the sixth issue he stares into the abyss and doesn't blink. There's no hope, no mercy, no reservation.

(Sandman #6.)

But in the sixth issue he stares into the abyss and doesn't blink. There's no hope, no mercy, no reservation.

(Sandman #6.)

Part of the bleakness of the sixth issue of Sandman rests in the way that Gaiman understands it's not Doctor Destiny himself that truly scares us.

It's the ugliness that lurks beneath the superficially "normal" exterior. The banality of human evil.

(Sandman #6.)

It's the ugliness that lurks beneath the superficially "normal" exterior. The banality of human evil.

(Sandman #6.)

In Gaiman's work, the expression of human evil is grotesque and horrifying.

But its roots are small-minded and mundane, narrow petty perspectives.

Gaiman returns to this idea with the "Cereal Convention." For all it's horror, evil is ultimately uninteresting.

(Sandman #6.)

But its roots are small-minded and mundane, narrow petty perspectives.

Gaiman returns to this idea with the "Cereal Convention." For all it's horror, evil is ultimately uninteresting.

(Sandman #6.)

I mean, there's still some humanism in this idea. That evil is boring, easy, unimaginative, animalistic. That everything that makes us human elevates us above this abyss.

But the sixth issue still makes that abyss look particularly haunting and gravity pulls hard.

(Sandman #6.)

But the sixth issue still makes that abyss look particularly haunting and gravity pulls hard.

(Sandman #6.)

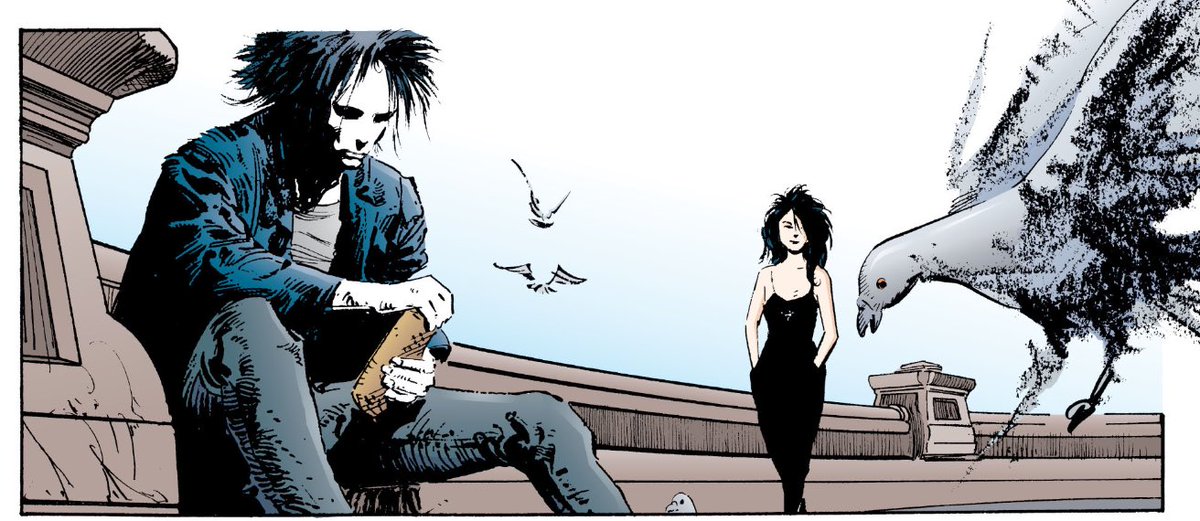

"The Sound of Her Wings" is one of those almost perfect single issues, to the point that I suspect it's been repackaged and reissued more often than any Neil Gaiman comic ever.

I own it at least twice in the prestige "Absolute" format.

(Sandman #8.)

I own it at least twice in the prestige "Absolute" format.

(Sandman #8.)

"The Sound of Her Wings" feels like not only the world of "Sandman" opening up, but also the register of its voice changing.

It feels like the first time Gaiman understands the breadth of what he can do with the series.

(Sandman #8.)

It feels like the first time Gaiman understands the breadth of what he can do with the series.

(Sandman #8.)

Gaiman's personification of Death as a perky, cheerful young woman was a radical.

It was such a great idea that it's now so common that it's almost become impossible to imagine when it was radical.

Death is fantastic. A brilliant twist on an old concept.

(Sandman #8.)

It was such a great idea that it's now so common that it's almost become impossible to imagine when it was radical.

Death is fantastic. A brilliant twist on an old concept.

(Sandman #8.)

As a side note, I love Mike Dringenberg and Malcolm Jones III's use of white space around Dream and Death in "The Sound of Her Wings."

It gives the pair room.

(Sandman #8.)

It gives the pair room.

(Sandman #8.)

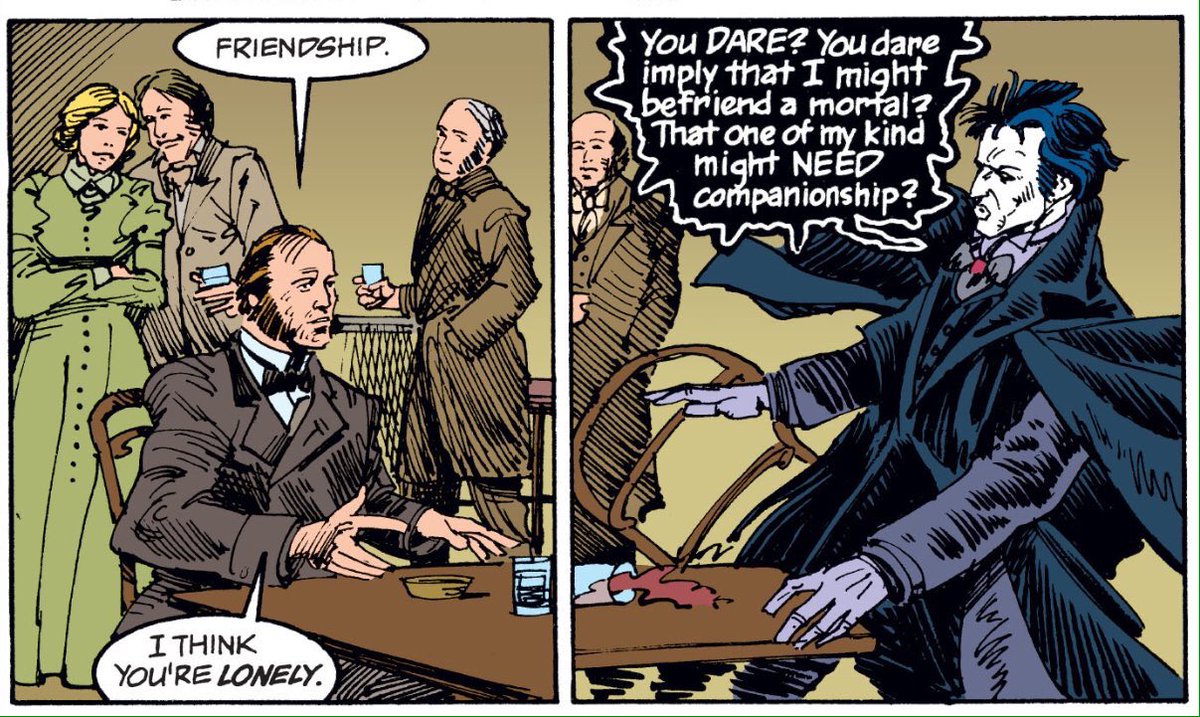

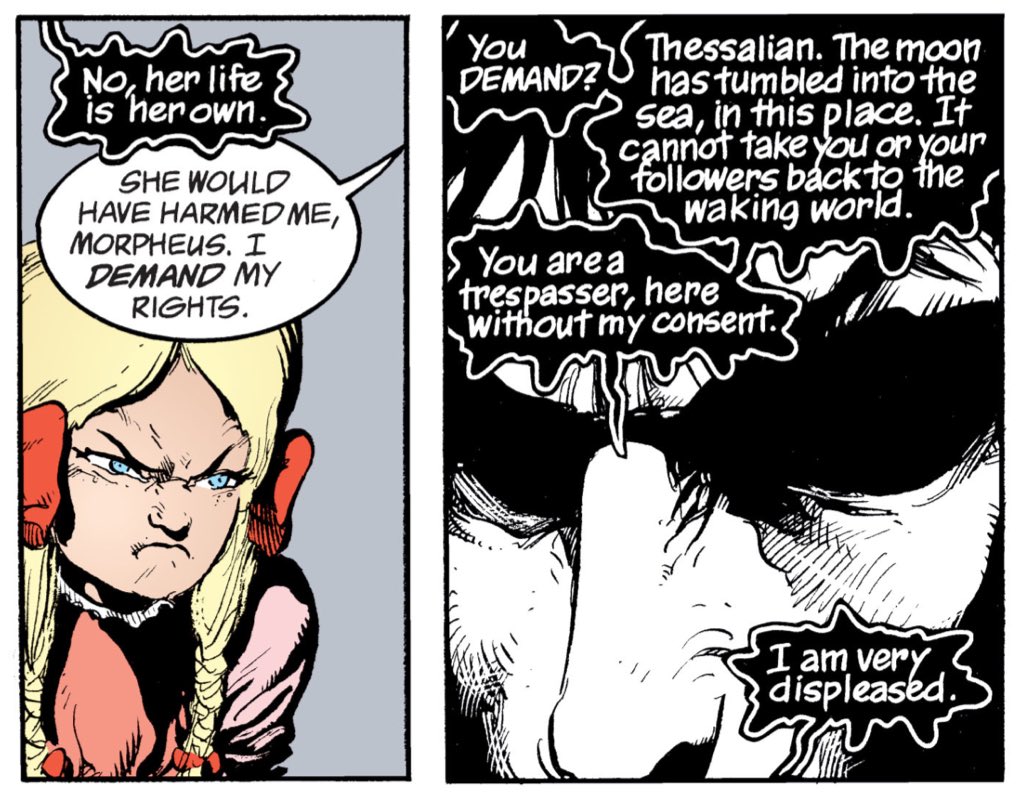

On thing I adore about "Sandman" is how Gaiman structures it as a tragedy.

The comic is utterly unafraid to call Dream out in his nonsense, acknowledge his flaws, even in the quiet and early issues.

He's our protagonist, but he's arrogant, proud and short-sighted.

(Sandman #8)

The comic is utterly unafraid to call Dream out in his nonsense, acknowledge his flaws, even in the quiet and early issues.

He's our protagonist, but he's arrogant, proud and short-sighted.

(Sandman #8)

And there's Neil Gaiman's warm, flowing humanism.

There's an incredible compassion and dignity in "The Sound of Her Wings." A profound empathy in the way Death greets these people at the end of their journey.

(Sandman #8.)

There's an incredible compassion and dignity in "The Sound of Her Wings." A profound empathy in the way Death greets these people at the end of their journey.

(Sandman #8.)

Saw this a bit too late to thread it properly, but apparently there’s a fan film adaptation of the aforementioned sixth issue.

Which is VERY impressive. But the sixth issue seems a very left-field choice for an adaptation of “Sandman.”

vimeo.com/223025116

Which is VERY impressive. But the sixth issue seems a very left-field choice for an adaptation of “Sandman.”

vimeo.com/223025116

There's something incredibly sweet in the way that Death loves life, in a manner that is not patronising or condescending.

She genuinely loves people, which is a lovely twist on the concept.

(Sandman #8.)

She genuinely loves people, which is a lovely twist on the concept.

(Sandman #8.)

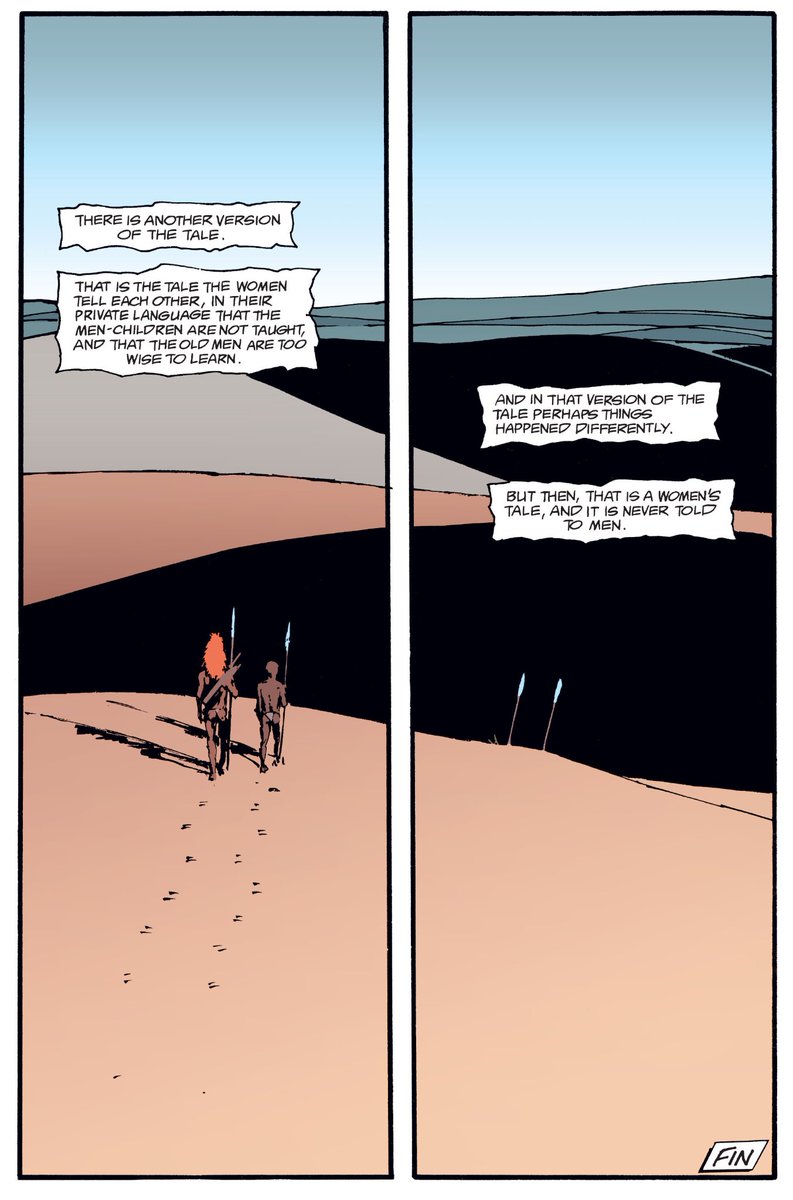

Cementing the idea that Gaiman is getting a handle on his creation, he follows "The Sound of Her Wings" with "Tales in the Sand."

It's a story that understands what "Sandman" is to be about. Not just dreams, but stories.

(Sandman #9.)

It's a story that understands what "Sandman" is to be about. Not just dreams, but stories.

(Sandman #9.)

Obviously, stories are a major thematic concern for Gaiman, a theme reiterated and revisited countless times in his work.

And, obviously, a series about dreams is going to touch on that.

But "Tales in the Sand" is the first time it truly comes to the fore.

(Sandman #9.)

And, obviously, a series about dreams is going to touch on that.

But "Tales in the Sand" is the first time it truly comes to the fore.

(Sandman #9.)

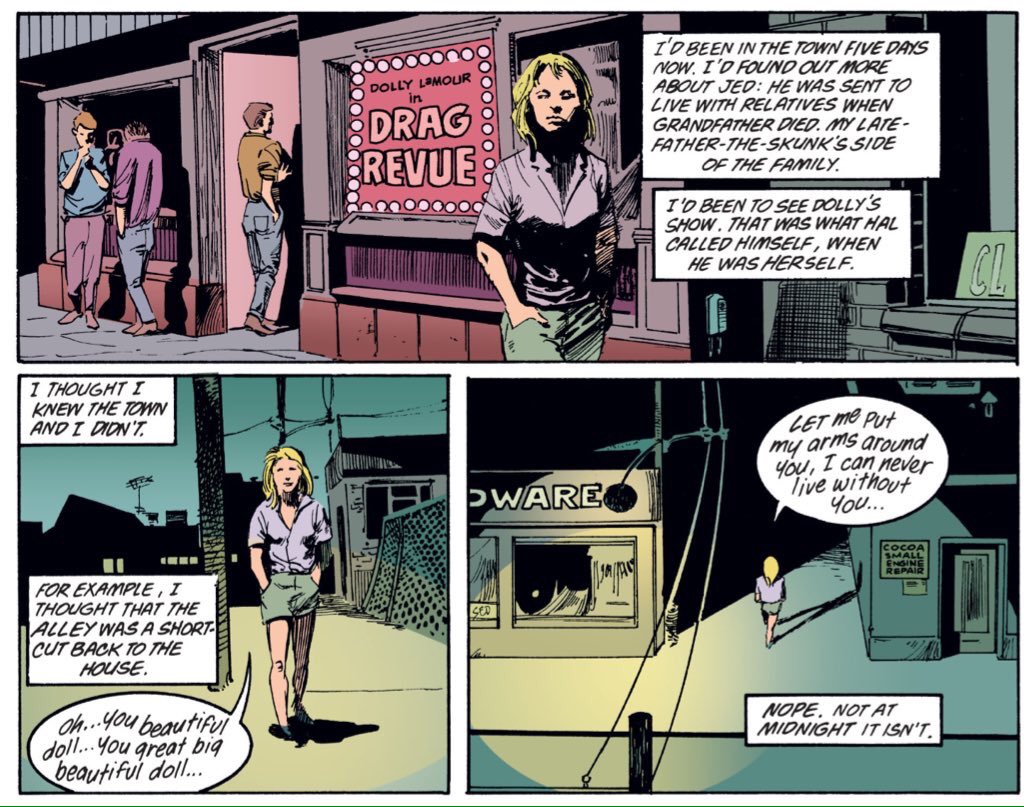

When I first read "Sandman" as a young teenager it was, along with Susan and Carol on "Friends", one of my first exposure to queer themes.

It really opened my eyes to how broad the spectrum of human experience could be, in a very empathic and humanist way.

(Sandman #11.)

It really opened my eyes to how broad the spectrum of human experience could be, in a very empathic and humanist way.

(Sandman #11.)

It isn't perfect. Even Gaiman admits he'd change stuff. (And more on that anon.)

But for a comic launched in 1989, read by a teen in Sligo about a decade later, it still felt revelatory.

An example of why representation is important even outside the community.

(Sandman #11.)

But for a comic launched in 1989, read by a teen in Sligo about a decade later, it still felt revelatory.

An example of why representation is important even outside the community.

(Sandman #11.)

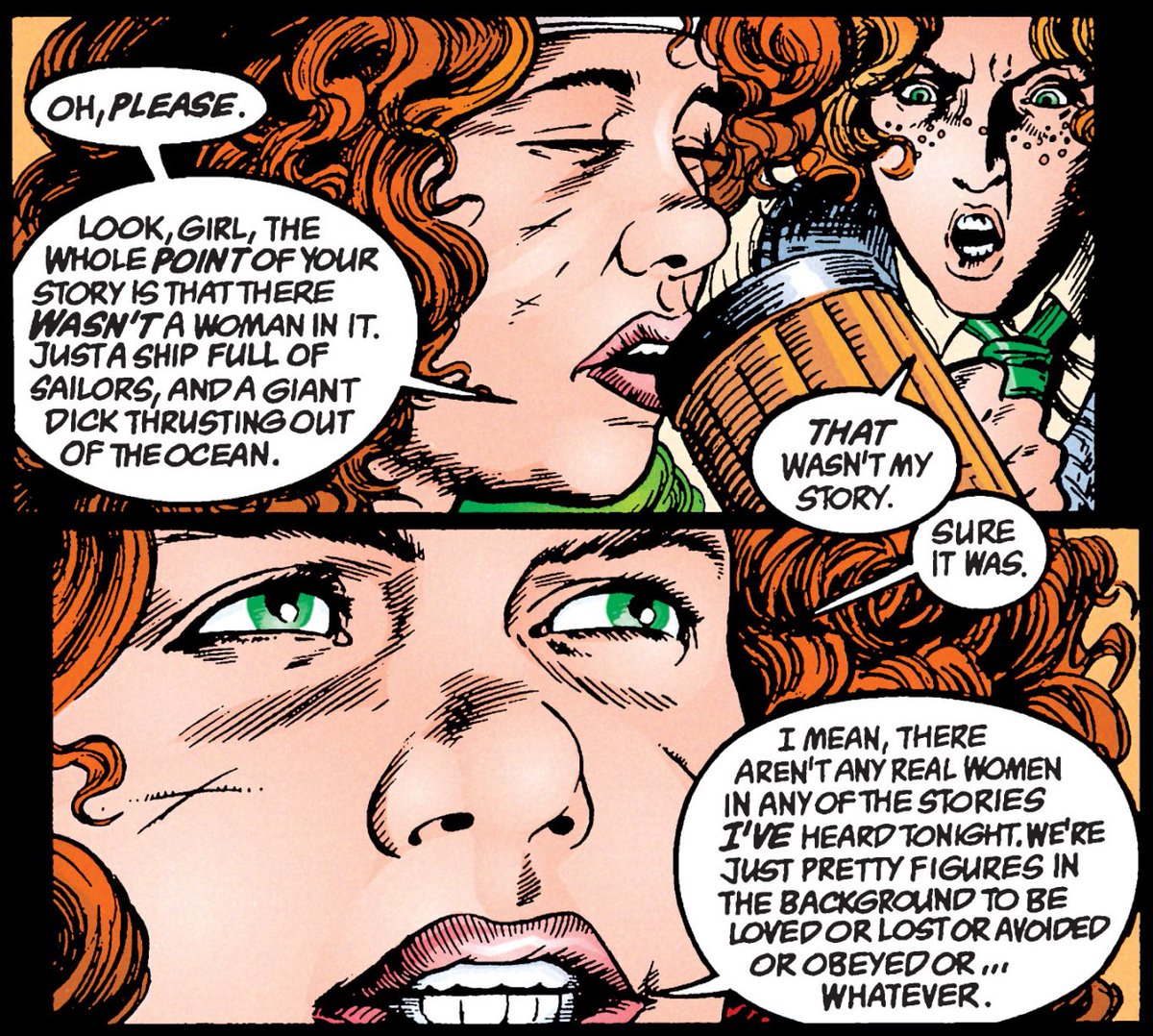

In keeping with this idea of diversity, that's another way in which "Tales in the Sand" serves to set up the larger themes of Gaiman's run.

It explicitly introduces the theme of gender into the epic, particularly the idea of gender as a prism or lens on story.

(Sandman #9.)

It explicitly introduces the theme of gender into the epic, particularly the idea of gender as a prism or lens on story.

(Sandman #9.)

In "Sandman", gender is a dividing line, a schism, a binary. One's position changes the nature of a story.

The story of Nada and Morpheus is different depending on which side of that line the character stands.

Desire's "Threshold" crosses that boundary.

(Sandman #10.)

The story of Nada and Morpheus is different depending on which side of that line the character stands.

Desire's "Threshold" crosses that boundary.

(Sandman #10.)

Of course, gender is not the only dividing line in "Sandman", although it's a big one.

"Sandman" repeatedly suggests that stories repeat and reiterate, echoing across reality.

Gaiman fills his story with parallels and juxtapositions.

(Sandman #12.)

"Sandman" repeatedly suggests that stories repeat and reiterate, echoing across reality.

Gaiman fills his story with parallels and juxtapositions.

(Sandman #12.)

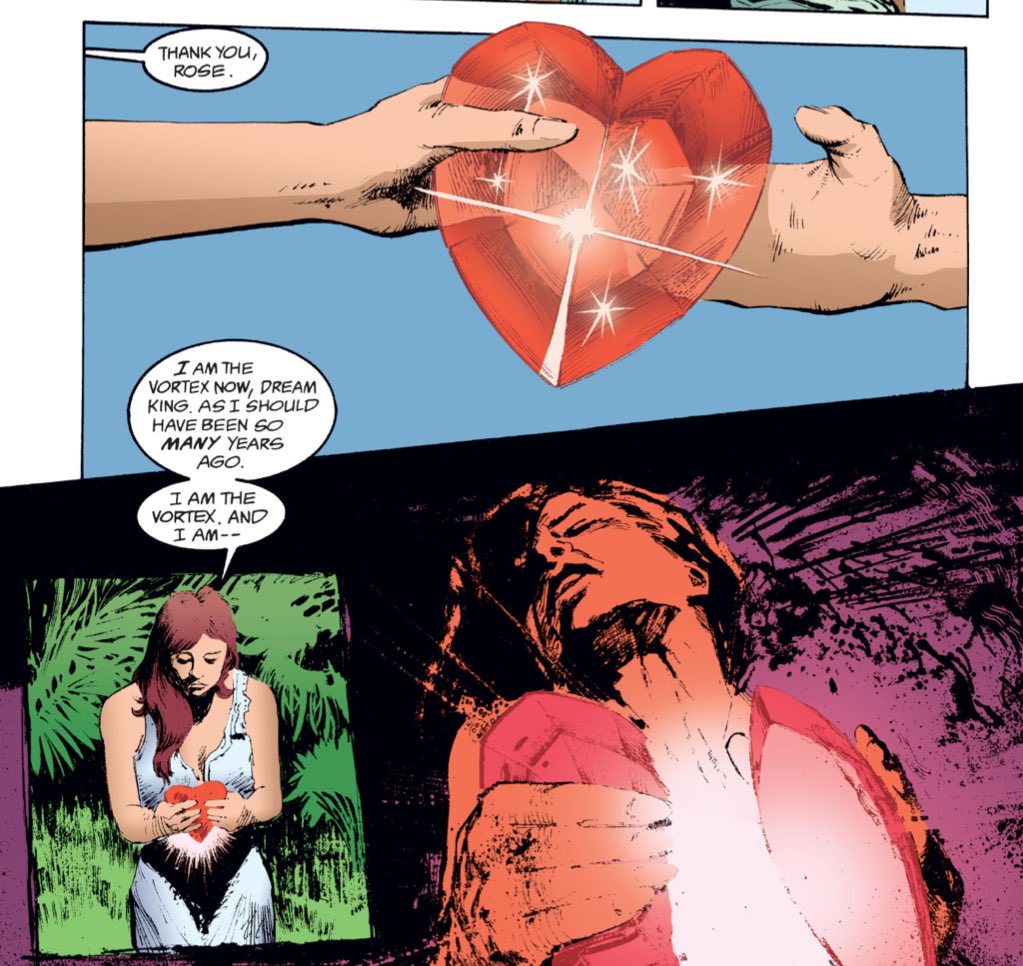

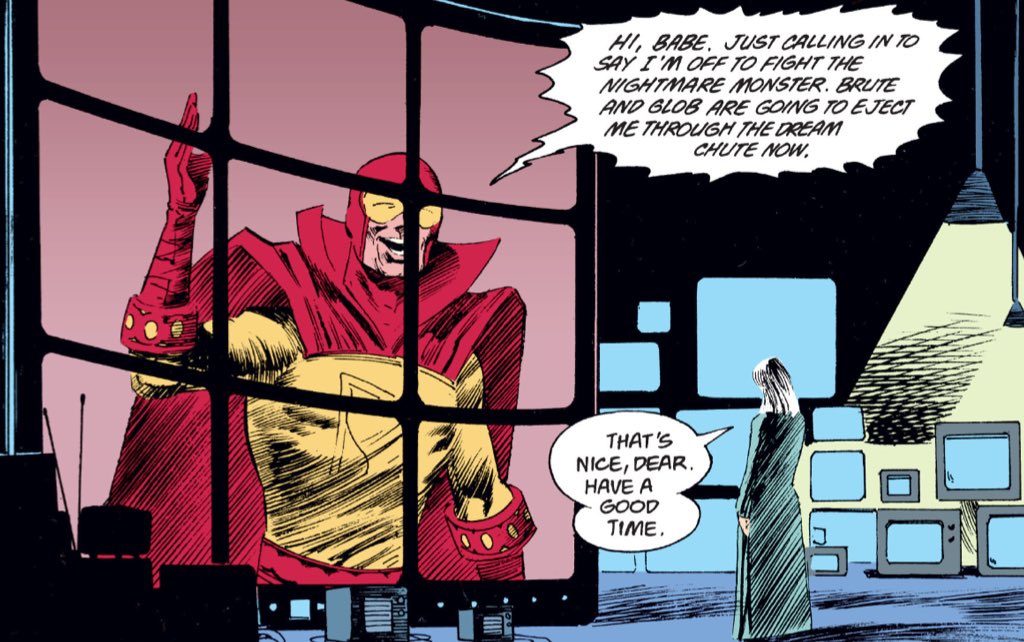

Reading "Sandman", one never has to look too far for some mirroring or some reflections.

Even in "The Doll House", Glob and Brute mirror Jed's abusive foster parents.

Almost any arrangement of three women evokes the Kindly Ones.

Echoes and refractions.

(Sandman #10.)

Even in "The Doll House", Glob and Brute mirror Jed's abusive foster parents.

Almost any arrangement of three women evokes the Kindly Ones.

Echoes and refractions.

(Sandman #10.)

It helps that Gaiman has a really good grasp of structure, allowing particular beats and ideas and images to echo through the series.

"Sandman" feels like a work put together with remarkable skill and precision. Full of set-up and pay-off.

(Sandman #9/17.)

"Sandman" feels like a work put together with remarkable skill and precision. Full of set-up and pay-off.

(Sandman #9/17.)

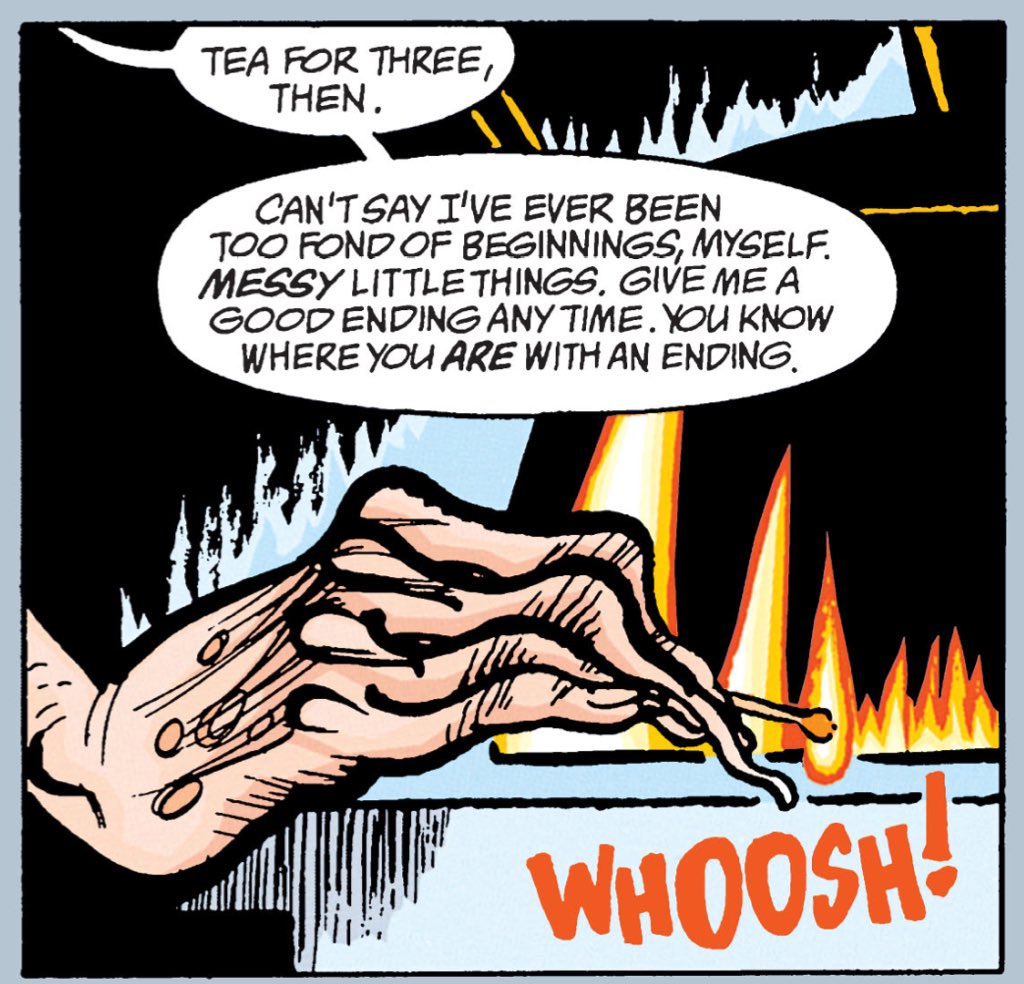

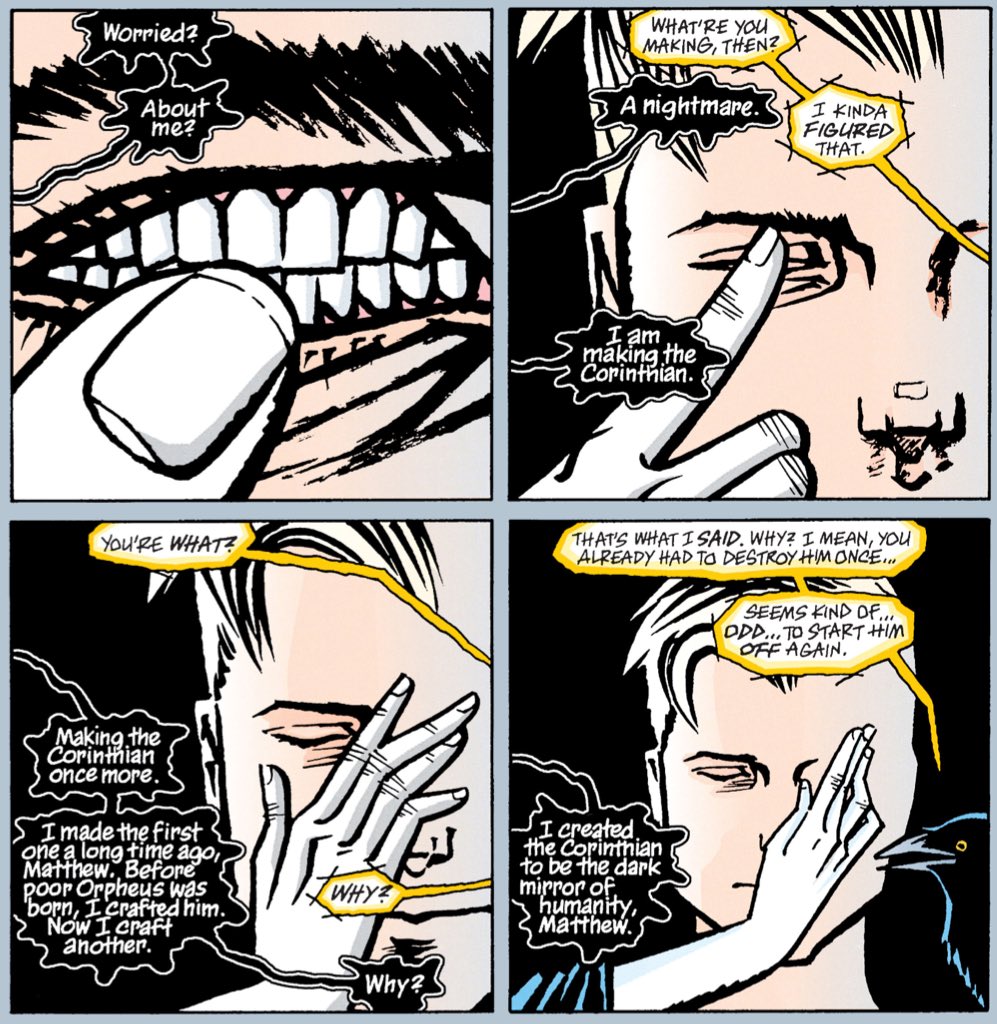

This repetition is more than structure. It's theme.

Life moves in cycles, stories and patterns repeat, whether because of who we are or simply because that's the way the world is.

Characters in "Sandman" are constantly being reinvented.

(Sandman #11.)

Life moves in cycles, stories and patterns repeat, whether because of who we are or simply because that's the way the world is.

Characters in "Sandman" are constantly being reinvented.

(Sandman #11.)

Abel is constantly murdered and reborn. Matthew is a character reborn from Alan Moore's "Swamp Thing." Dream eventually remakes the Corinthian.

Even Dream himself undergoes radical and profound change in "Sandman."

(Sandman #11.)

Even Dream himself undergoes radical and profound change in "Sandman."

(Sandman #11.)

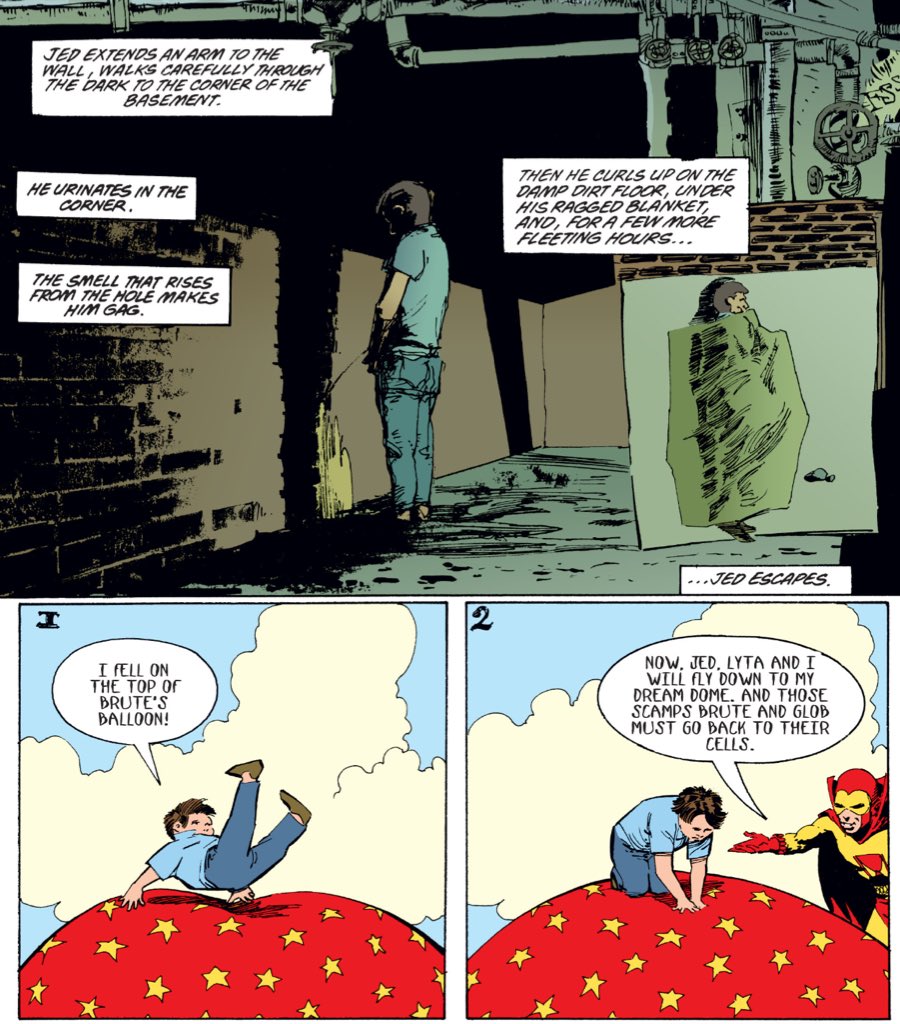

"The Doll House" marks a transitional phase for "Sandman."

The series is moving away from the DC Universe and out of the horror genre towards it's more recognisable self.

Here, Gaiman's still playing with DC continuity; Kirby's "Sandman", "Infinity Inc."

(Sandman #11.)

The series is moving away from the DC Universe and out of the horror genre towards it's more recognisable self.

Here, Gaiman's still playing with DC continuity; Kirby's "Sandman", "Infinity Inc."

(Sandman #11.)

The pivot away from this shared superhero universe can be seen in how Morpheus responds to a more conventionally super heroic interpretation of "The Sandman", Hector Hall.

(Sandman #12.)

(Sandman #12.)

"The Doll House" also plays the single most 80s "superheroes are childish nonsense" grim 'n' gritty twist ever.

Hector Hall lives in the fantasies of an abused boy, Jed.

As an aside, the cute panel numbering carrying over to the abuse is a particularly grim joke.

(Sandman #11)

Hector Hall lives in the fantasies of an abused boy, Jed.

As an aside, the cute panel numbering carrying over to the abuse is a particularly grim joke.

(Sandman #11)

The Jed plot almost plays as a parody of the "superheroes are grown up now!" nonsense that became so popular after "Dark Knight Returns" and "Watchmen."

It's a credit to Gaiman that it doesn't feel as trite or reactionary.

(Sandman #11.)

It's a credit to Gaiman that it doesn't feel as trite or reactionary.

(Sandman #11.)

If the Jed plot is "Sandman" bidding farewell to superhero stuff, then the Corinthian stuff is "Sandman" bidding farewell to the kind of "Swamp Thing"/"Hellblazer"/archetypal Vertigo stuff.

It's the horrific "outsider views America" stuff.

(Sandman #11.)

It's the horrific "outsider views America" stuff.

(Sandman #11.)

Even in the introduction of Lyta Hall, there's a sense of a female character whose own arc and story has been subsumed by those of the men around her. As with Nada, and others.

She's trapped by Hector's fantasies and wounded by Morpheus' own narrative.

(Sandman #11.)

She's trapped by Hector's fantasies and wounded by Morpheus' own narrative.

(Sandman #11.)

By the way, here’s Neil Gaiman on how he gendered the various arcs of “Sandman.”

neilgaiman.com/p/Cool_Stuff/E…

neilgaiman.com/p/Cool_Stuff/E…

As with Alan Moore, whose work was a major influence on the younger writer, Neil Gaiman has always had an incredible knack for capturing very "human" moments in the most fantastical premises.

There's a profound sadness to Lyta Hall, trapping in a child's fantasy.

(Sandman #12.)

There's a profound sadness to Lyta Hall, trapping in a child's fantasy.

(Sandman #12.)

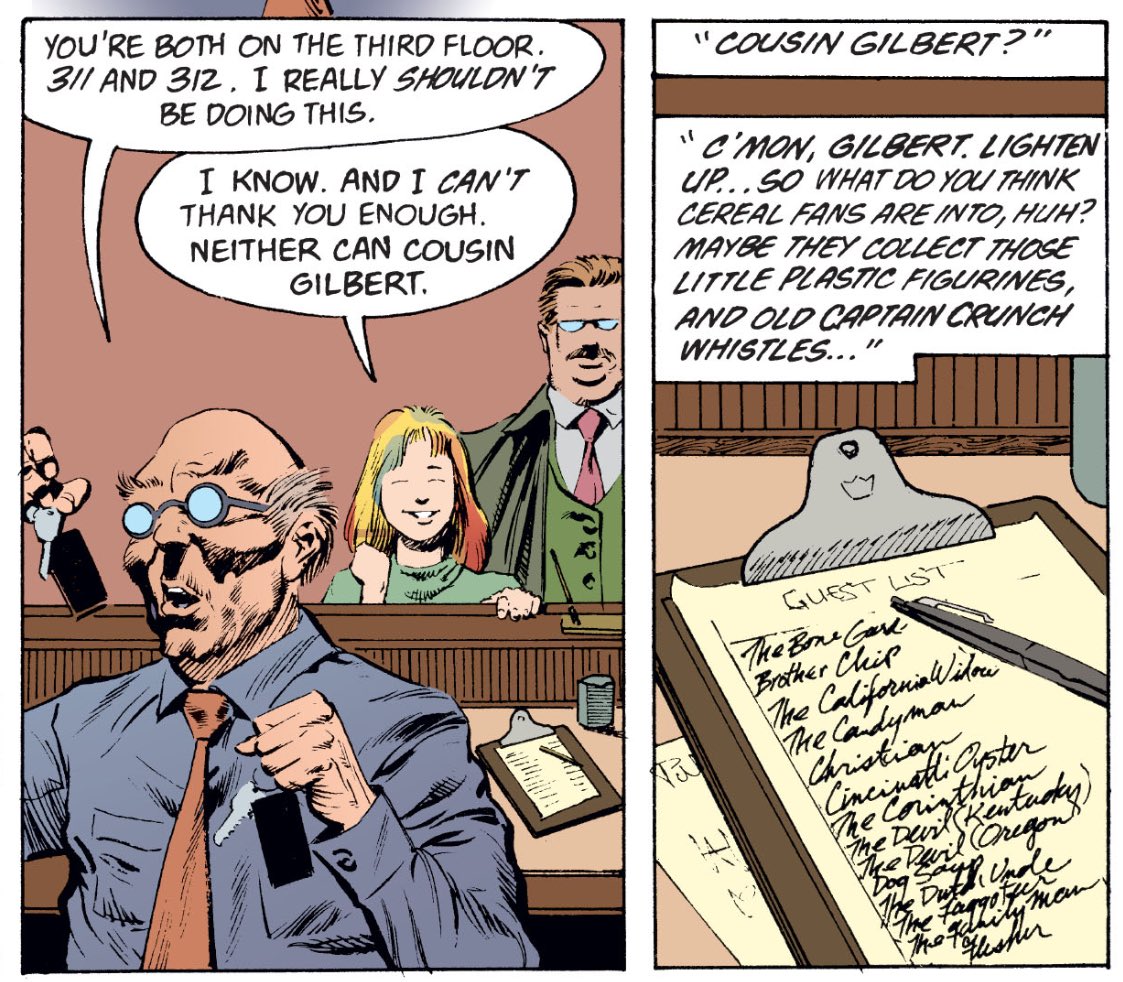

The serial killer story in "The Doll House" is Gaiman riffing on archetypal themes, such as the idea of serial killers as collectors.

This is obviously rooted in their pathology, but is also a common literary device. Dating back to at least... eh, "The Collector."

(Sandman #12)

This is obviously rooted in their pathology, but is also a common literary device. Dating back to at least... eh, "The Collector."

(Sandman #12)

Another sign of Gaiman finding his feet with "The Doll House", interrupting the main arc for a poetic standalone "Men of Good Fortune."

He arguably did this with the sixth issue of the opening arc, but this is much more obviously something completely different.

(Sandman #12.)

He arguably did this with the sixth issue of the opening arc, but this is much more obviously something completely different.

(Sandman #12.)

Hob Gadling is an incredible character.

He's Gaiman playing with the hoary old trope that every immortal must eventually long for death, a common literary cliché.

Keeping with Gaiman's humanism, Gadling just loves life. It's heartening.

(Sandman #13.)

He's Gaiman playing with the hoary old trope that every immortal must eventually long for death, a common literary cliché.

Keeping with Gaiman's humanism, Gadling just loves life. It's heartening.

(Sandman #13.)

In keeping with the emphasis on stories within "Sandman", I always loved that Hob becomes immortal simply by declaring that he's not going to die. Words and narrative.

He becomes a story that never ends. A literal "Endless", perhaps even like a comics character.

(Sandman #13.)

He becomes a story that never ends. A literal "Endless", perhaps even like a comics character.

(Sandman #13.)

Morpheus' fascination with (and, yes, affection for) Hob also serves to humanise him as well. Particularly given he just (to the audience) killed Lyta's husband and promised to steal her baby.

Morpheus, like Gaiman, is just intrigued by people.

(Sandman #13.)

Morpheus, like Gaiman, is just intrigued by people.

(Sandman #13.)

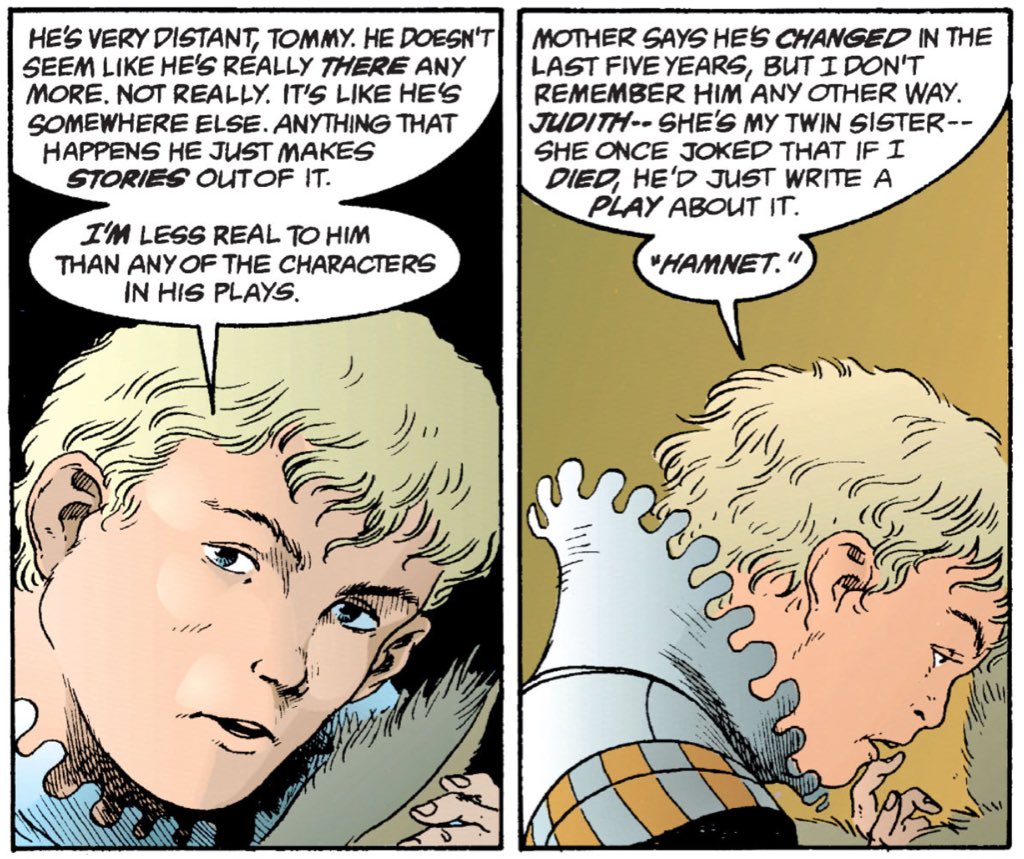

Speaking of Gaiman getting the hang of the book, there's also a sense of a long game emerging in terms of big picture and small details.

The first year has PLENTY of foreshadowing, but the Shakespeare cameo here is a lot more explicitly purposeful.

(Sandman #13.)

The first year has PLENTY of foreshadowing, but the Shakespeare cameo here is a lot more explicitly purposeful.

(Sandman #13.)

Even having lost everything, even starving, even ruined, Hob still refuses to surrender himself to death.

"Sandman" could occasionally get quite dark, but little beats like this reveal it as a work of genuine warmth.

(Sandman #13.)

"Sandman" could occasionally get quite dark, but little beats like this reveal it as a work of genuine warmth.

(Sandman #13.)

At the same time, as with the serial killer convention, Gaiman is still scribbling at the edges of what would become Vertigo.

(Sandman #13.)

(Sandman #13.)

Hm. Is this foreshadowing?

I love that Gaiman's writing is so ambiguous that it could be, but also might not be.

(Sandman #13.)

I love that Gaiman's writing is so ambiguous that it could be, but also might not be.

(Sandman #13.)

A big theme of "Sandman" is how Morpheus changes, and how he deals with that change.

In the final two pages of "Men of Good Fortune", effectively bookending the first year (twelve issues) of "Sandman", Gaiman illustrates how much Morpheus has already changed.

(Sandman #13.)

In the final two pages of "Men of Good Fortune", effectively bookending the first year (twelve issues) of "Sandman", Gaiman illustrates how much Morpheus has already changed.

(Sandman #13.)

"I've seen people, and they don't change."

Gaiman's too much of an optimist to buy into this. Indeed, Hob's proven wrong the very next page.

One of the big arcs of "Sandman" is Morpheus confronting the fact that he CAN and DOES change.

(Sandman #13.)

Gaiman's too much of an optimist to buy into this. Indeed, Hob's proven wrong the very next page.

One of the big arcs of "Sandman" is Morpheus confronting the fact that he CAN and DOES change.

(Sandman #13.)

Nice subtle shoutout to Jamie Delano's underrated "Hellblazer" run here.

"The Family Man" can't make it because John Constantine killed him.

It's a nice little unintrusive reference, like make Matthew the character from "Swamp Thing."

(Sandman #14.)

"The Family Man" can't make it because John Constantine killed him.

It's a nice little unintrusive reference, like make Matthew the character from "Swamp Thing."

(Sandman #14.)

In one of those nice synchronicities, given that I was talking about how change is one of the key themes of “Sandman”, this crossed my timeline.

I’m not sure what I have to say about it, but just thought it was worth threading.

I’m not sure what I have to say about it, but just thought it was worth threading.

https://twitter.com/mattzollerseitz/status/1033048991519391744?s=21

It's worth noting how skilful Gaiman is with these continuity references.

I'd read (and reread) "Sandman" years ago, and never felt I was missing something.

But when I came back after reading "Hellblazer" and "Swamp Thing", so much clicked into place.

(Sandman #14.)

I'd read (and reread) "Sandman" years ago, and never felt I was missing something.

But when I came back after reading "Hellblazer" and "Swamp Thing", so much clicked into place.

(Sandman #14.)

In the world of "Sandman", where change is a major theme of the work itself, even stories themselves change over time.

Here, Gilbert - a story who has also changed himself - contrasts the original story of "Little Red Riding Hood."

(Sandman #14.)

Here, Gilbert - a story who has also changed himself - contrasts the original story of "Little Red Riding Hood."

(Sandman #14.)

"Collectors" is the archetypal story you'd expect from the comics that readers see as the foundation stone of Vertigo.

It's a story looking at America from the perspective of sophisticated, literary British writers.

Here, the idea of serial killer as celebrity.

(Sandman #14.)

It's a story looking at America from the perspective of sophisticated, literary British writers.

Here, the idea of serial killer as celebrity.

(Sandman #14.)

I mean, the title page of "Collectors" all but screams, "This is an important statement about America!"

In the late eighties and early nineties, highbrow, prestige culture engaged consciously with the idea of the serial killer as the avatar of America.

(Sandman #14.)

In the late eighties and early nineties, highbrow, prestige culture engaged consciously with the idea of the serial killer as the avatar of America.

(Sandman #14.)

The serial killer is a fascinating figure in American popular culture. I was (and still am) a intrigued by how pop culture treats them.

The can be an avatar of concepts like celebrity and random violence, as they were after the Cold War and before 9/11.

press.uchicago.edu/Misc/Chicago/7…

The can be an avatar of concepts like celebrity and random violence, as they were after the Cold War and before 9/11.

press.uchicago.edu/Misc/Chicago/7…

“A Walk Among the Tombstones” is not a good film, but I always loved its final reveal.

It’s a puppy serial killer movie, but the final shot reveals it took place before 9/11.

Which is arguably the place in American popular culture where the serial killer belongs.

It’s a puppy serial killer movie, but the final shot reveals it took place before 9/11.

Which is arguably the place in American popular culture where the serial killer belongs.

The last few years have seen a minor resurgence in serial killer pop culture; “Criminal Minds”, “Mind Hunter”, “Sharp Objects”, even “True Detective.”

But in the 2000s and early 2010s, the serial killer felt curiously outdated as an American boogeyman.

slate.com/articles/news_…

But in the 2000s and early 2010s, the serial killer felt curiously outdated as an American boogeyman.

slate.com/articles/news_…

Some of this is undoubtedly cultural.

Serial killers had a “moment” in the 1990s, between the end of the Cold War and 9/11 because they embodies a sort of nihilistic random brutality.

The fear of the 1990s. They’ve since been supplanted by terrorists.

bustle.com/articles/11213…

Serial killers had a “moment” in the 1990s, between the end of the Cold War and 9/11 because they embodies a sort of nihilistic random brutality.

The fear of the 1990s. They’ve since been supplanted by terrorists.

bustle.com/articles/11213…

All of this is to provide a context for Gaiman's handling of serial killers in "Collectors." Cover dated March 1990 and art dated 1989.

Pop culture was heading into the decade of "Silence of the Lambs", "se7en", "Natural Born Killers", etc.

(Sandman #14.)

Pop culture was heading into the decade of "Silence of the Lambs", "se7en", "Natural Born Killers", etc.

(Sandman #14.)

Gaiman is in some ways consciously reacting against the fascination that American popular culture has with serial killers.

Even before the story's climax, "Collectors" emphasises how pathetic these men truly are.

(Sandman #14.)

Even before the story's climax, "Collectors" emphasises how pathetic these men truly are.

(Sandman #14.)

There's a sense in which "Collectors" is archetypal Vertigo storytelling.

It's a pulpy narrative about serial killers, intertwined with cultural commentary about fame and celebrity.

It owes a massive debt to Alan Moore's work on "American Gothic."

(Sandman #14.)

It's a pulpy narrative about serial killers, intertwined with cultural commentary about fame and celebrity.

It owes a massive debt to Alan Moore's work on "American Gothic."

(Sandman #14.)

This little exchange reminds me of the handling of William in "Westworld." Doctor, philanthropist, all-round do-gooder; and complete monster.

(Sandman #14.)

(Sandman #14.)

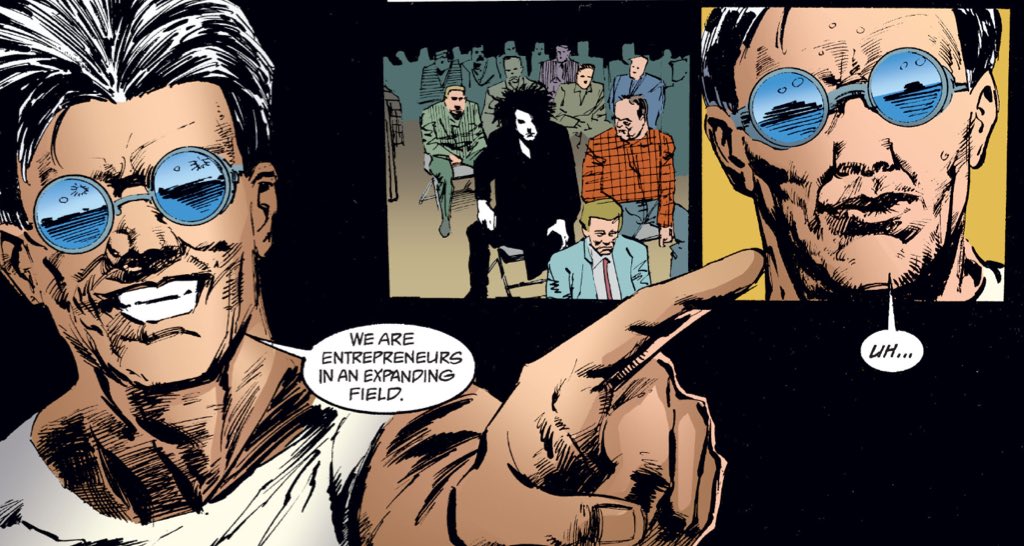

"Collectors" repeatedly uses serial killers as a grotesque and horrific prism into American popular culture, perhaps reflecting Gaiman's outsider perspective.

It ties serial killers to American fascinations like celebrity, but also capitalism.

(Sandman #14.)

It ties serial killers to American fascinations like celebrity, but also capitalism.

(Sandman #14.)

Another sly continuity nod to Vertigo, "The Bogeyman" was featured in (and killed off in) Alan Moore's "Swamp Thing."

Again, it's a nice piece of continuity that is unobtrusive, and doesn't alienate readers with no familiarity with Moore's work.

(Sandman #14.)

Again, it's a nice piece of continuity that is unobtrusive, and doesn't alienate readers with no familiarity with Moore's work.

(Sandman #14.)

In this context, the Corinthian is a fascinating character.

In particular the idea that his eyes are actually mouths. It makes the act of watching equivalent to the act of consumption, which feels itself a commentary on American popular culture.

(Sandman #14.)

In particular the idea that his eyes are actually mouths. It makes the act of watching equivalent to the act of consumption, which feels itself a commentary on American popular culture.

(Sandman #14.)

“How do we begin to covet, Clarice? Do we seek out things to covet? No. We begin by coveting what we see every day.”

The Corinthian, with mouths for eyes, reminds me of the above quote from “Silence of the Lambs.”

The Corinthian literally hungers for and consumes what he sees.

The Corinthian, with mouths for eyes, reminds me of the above quote from “Silence of the Lambs.”

The Corinthian literally hungers for and consumes what he sees.

Even in the context of this story about serial killers, Gaiman is playing with the idea of serial killers as a modern myth, a story, a narrative.

They are the modern equivalent of the wolf from those fairytales, as literalised Funland's choice of shirt.

(Sandman #14.)

They are the modern equivalent of the wolf from those fairytales, as literalised Funland's choice of shirt.

(Sandman #14.)

One of the most unlikely legacies of "Sandman" is that Kevin Smith (of all writers) would eventually resurrect "Funland" (of all characters) in "Batman: The Widening Gyre" (of all stories).

(Sandman #14.)

(Sandman #14.)

Repeatedly in "Collectors", the Corinthian positions himself as an avatar of the American Dream.

This perhaps fits with the horror of his eyes as mouths, tying into themes of capitalism and consumerism and appetite.

The dark twisted nemesis of the nation.

(Sandman #14.)

This perhaps fits with the horror of his eyes as mouths, tying into themes of capitalism and consumerism and appetite.

The dark twisted nemesis of the nation.

(Sandman #14.)

There is also a sense with "Collectors" that Gaiman is gently parodying those sorts of pretentious self-important serial killer narratives, the idea that they are profound or deep reflections of contemporary pop culture.

(Sandman #14.)

(Sandman #14.)

Morpheus is singularly unimpressed with the idea of the serial killers inspired by the Corinthian.

Much like Morpheus' casual dismissal of Hector Hall, this suggests "Sandman" moving beyond the template set by writers like Alan Moore and Jamie Delano.

(Sandman #14.)

Much like Morpheus' casual dismissal of Hector Hall, this suggests "Sandman" moving beyond the template set by writers like Alan Moore and Jamie Delano.

(Sandman #14.)

This beat, in which Morpheus strips away the fantasies of victimhood that enable/perpetuate this violence and anger, has aged well.

It plays into the themes of story running through the series, but also could apply just as readily to modern misogynists/racists.

(Sandman #14.)

It plays into the themes of story running through the series, but also could apply just as readily to modern misogynists/racists.

(Sandman #14.)

It's a very poetic conclusion, and one that could apply just as readily to any monsters who rationalise their beliefs through self-aggrandising narratives.

I always loved the ending of stripping away someone's fantasies and forcing them to see themselves.

(Sandman #14.)

I always loved the ending of stripping away someone's fantasies and forcing them to see themselves.

(Sandman #14.)

It wasn't essential - prequels rarely are - but I did appreciate "Sandman Overture" explaining why Morpheus was so committed to resolving the vortex crisis by any means necessary.

(Sandman #15.)

(Sandman #15.)

Another subtle, unintrusive allusion to "Swamp Thing", the cornerstone of early "Sandman."

(Sandman #15.)

(Sandman #15.)

A nice, quiet call back to the sixth issue of the series.

Gaiman employed these callbacks very artfully in "Sandman", creating a web of connections that felt organic rather than engineered.

Human lives, interlocked in small and powerful ways.

(Sandman #16.)

Gaiman employed these callbacks very artfully in "Sandman", creating a web of connections that felt organic rather than engineered.

Human lives, interlocked in small and powerful ways.

(Sandman #16.)

But Gaiman cast his gaze forward as often as he looked backwards.

The final reveals in "The Dolls House" seed the end of then entire seventy-odd issue series.

(Sandman #16.)

The final reveals in "The Dolls House" seed the end of then entire seventy-odd issue series.

(Sandman #16.)

Just before moving on from "The Doll's House", it's worth comparing the title page of "Collectors" to the cover of the issue of "Swamp Thing" that introduced "The Bogeyman."

(Sandman #14/Swamp Thing #44.)

(Sandman #14/Swamp Thing #44.)

Gaiman follows the epic feel of "The Doll's House" with a series of one-shots, collected as "Dream Country."

Though he'd done one-shots before ("Tales in the Sand", "The Sound of Her Wings", "Men of Good Fortune"), he never did so many so close together.

(Sandman #17.)

Though he'd done one-shots before ("Tales in the Sand", "The Sound of Her Wings", "Men of Good Fortune"), he never did so many so close together.

(Sandman #17.)

These collections of single-issue done-in-one stories (occasionally arranged by theme) would become as much a hallmark of "Sandman" as the epic, sweeping arcs.

They're a pretty good gateway into "Sandman." Interested readers can dip their toes into these stories.

(Sandman #17.)

They're a pretty good gateway into "Sandman." Interested readers can dip their toes into these stories.

(Sandman #17.)

I mean, if you wanted to get a taste for "Sandman", I'd recommend a half-dozen of these short stories.

Maybe not "Calliope." It's very good, but it's also one of those incredibly uncomfortable stories. It's not for everyone.

(Sandman #17.)

Maybe not "Calliope." It's very good, but it's also one of those incredibly uncomfortable stories. It's not for everyone.

(Sandman #17.)

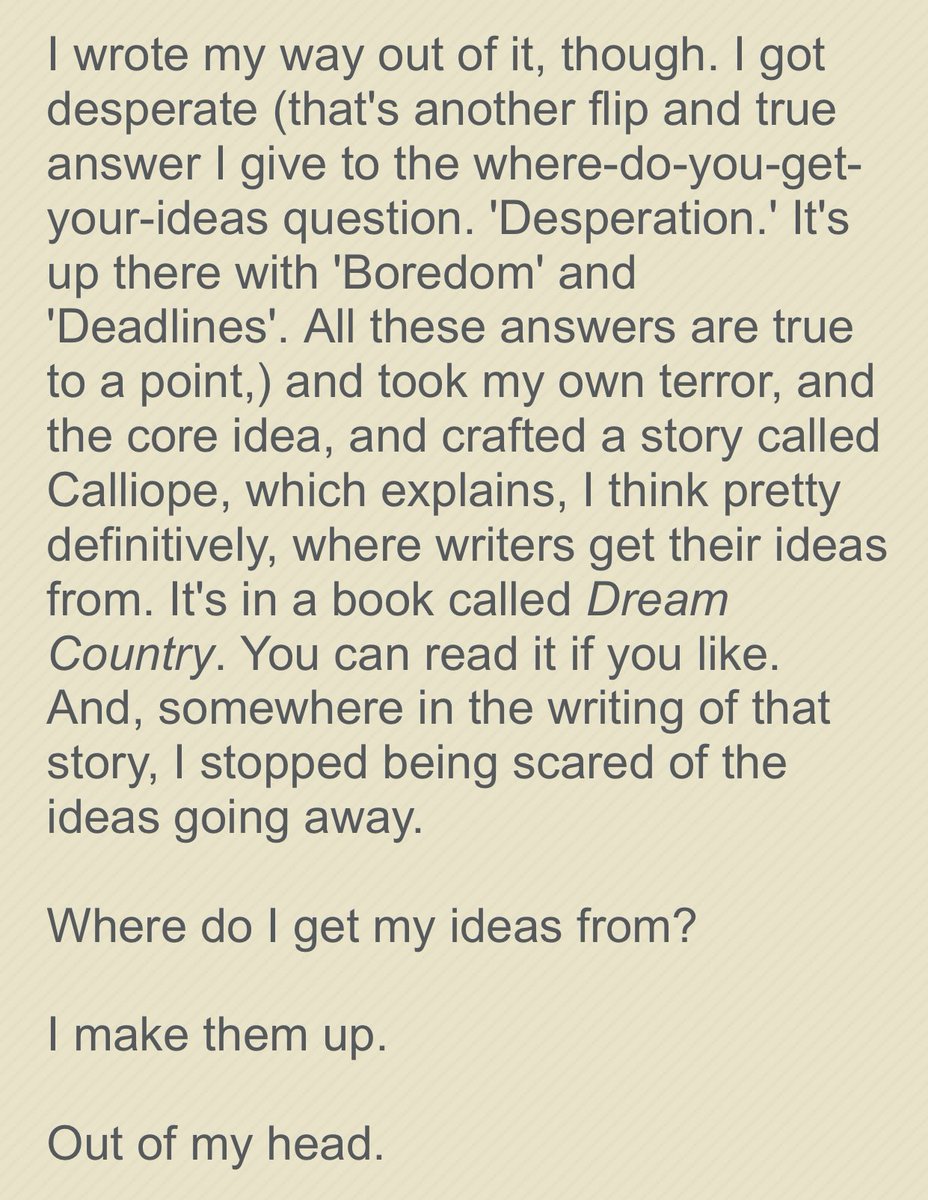

“Calliope”, and “Dream Country”, arrived as Gaiman grappled with the demands of comics pacing; having to churn out ideas in rapid succession.

He struggled a bit at the time, and his anxieties can be seen in “Calliope” and “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.”

bookbrowse.com/author_intervi…

He struggled a bit at the time, and his anxieties can be seen in “Calliope” and “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.”

bookbrowse.com/author_intervi…

"Calliope" is a story about where writers get their ideas from. And the answer that the comic presents is horrifying.

There's something very raw and very brutal about Gaiman writing about writers' block.

(Sandman #17.)

There's something very raw and very brutal about Gaiman writing about writers' block.

(Sandman #17.)

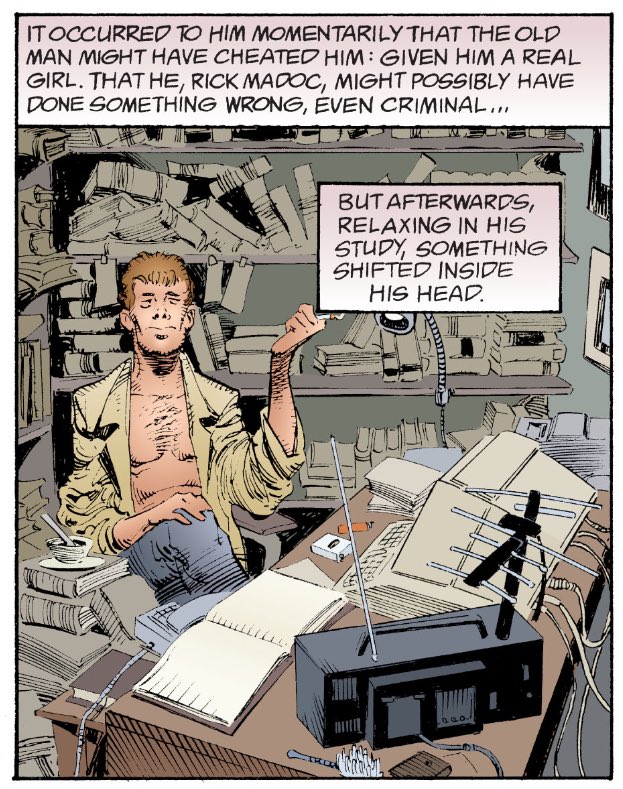

Madoc, the character from "Calliope", is a character important to the author even beyond his position as a one-shot guest character.

Notably, Gaiman makes a point to give Maddox some merciful closure almost half a decade after his only appearance.

(Sandman #70/72.)

Notably, Gaiman makes a point to give Maddox some merciful closure almost half a decade after his only appearance.

(Sandman #70/72.)

"Calliope" is a thematic bridge between "The Doll's House" & "Season of Mists."

In "Collectors", (mostly) male killers perpetrated violence against (mostly) female victims to fuel internal narratives.

In "Calliope", Madoc victimises Calliope to fuel his stories.

(Sandman #17.)

In "Collectors", (mostly) male killers perpetrated violence against (mostly) female victims to fuel internal narratives.

In "Calliope", Madoc victimises Calliope to fuel his stories.

(Sandman #17.)

"Sandman" is full of men who victimise or entrap women to further their own narratives, whether internal or external.

Hector and Lyta Hall; the serial killers in "Collectors"; Madoc.

Even "Season of Mists" is driven by Morpheus trying to atone for trapping Nada.

(Sandman #17.)

Hector and Lyta Hall; the serial killers in "Collectors"; Madoc.

Even "Season of Mists" is driven by Morpheus trying to atone for trapping Nada.

(Sandman #17.)

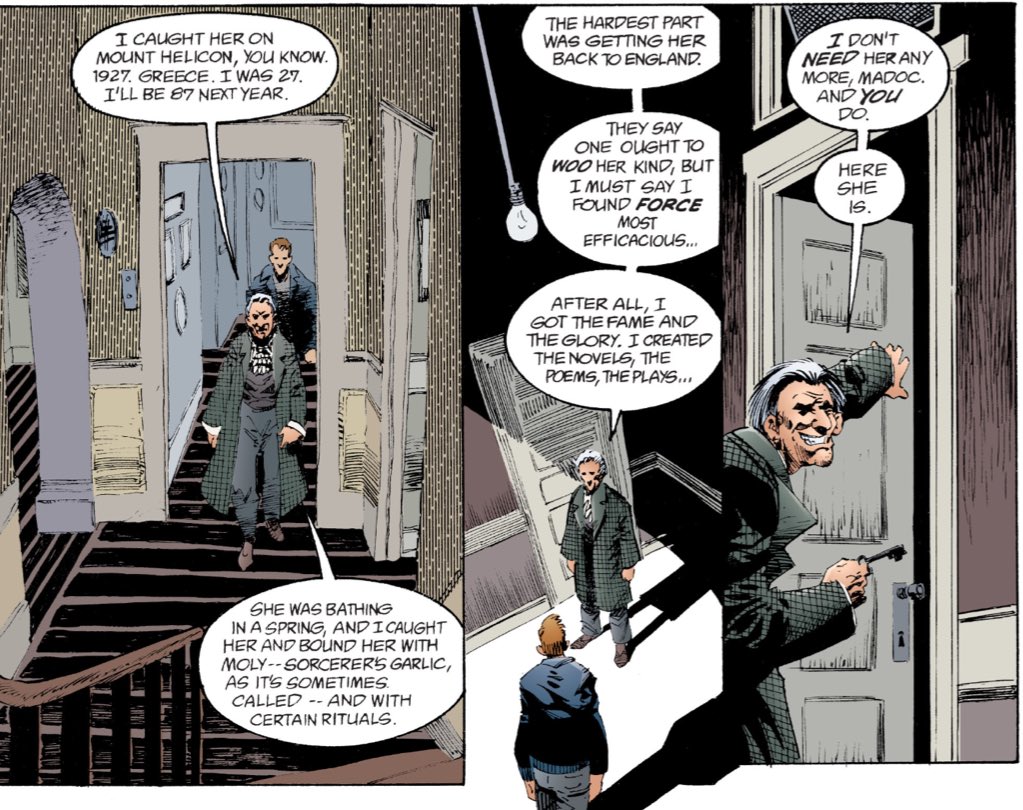

"Calliope" also points forwards to "Season of Mists" with its emphasis on arbitrary (and completely amoral) systems of rules and codes that govern the world.

Calliope is not bound by chains or bars, but by "moly" and "certain rituals."

(Sandman #17.)

Calliope is not bound by chains or bars, but by "moly" and "certain rituals."

(Sandman #17.)

"... you are lawfully bound."

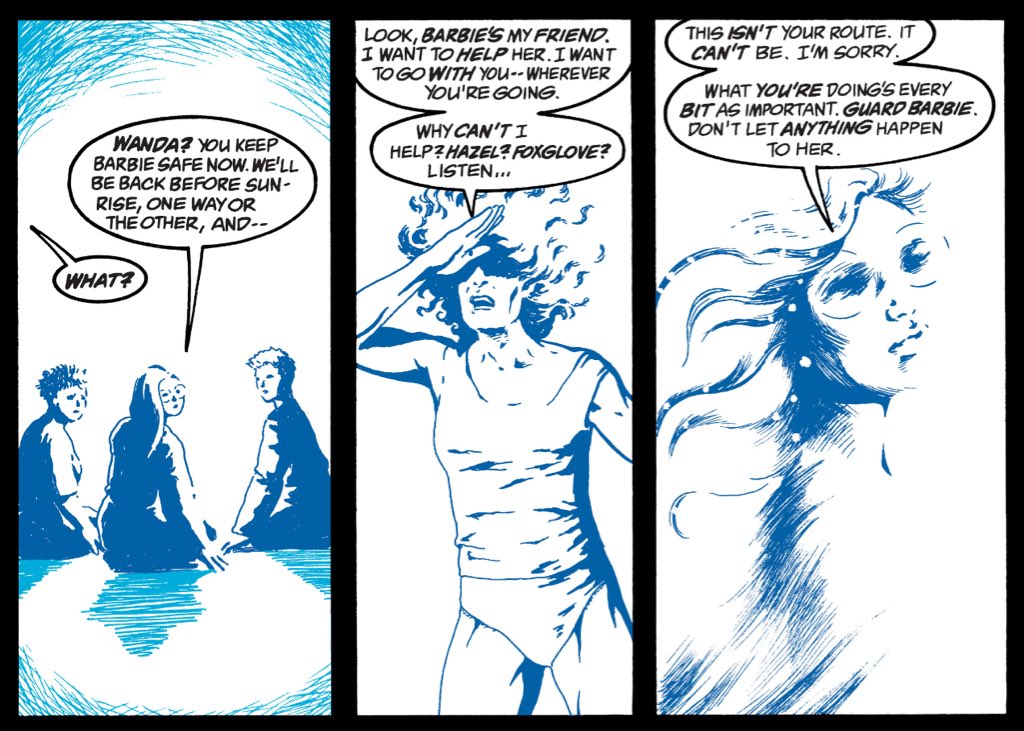

"Sandman" returns time and time again to the cruelty of arbitrary and archaic rules that trap us.

Think of the hospitality in "Season of Mists", the death of Wanda in "A Game of You", the hounding of Morpheus in "The Kindly Ones."

(Sandman #17.)

"Sandman" returns time and time again to the cruelty of arbitrary and archaic rules that trap us.

Think of the hospitality in "Season of Mists", the death of Wanda in "A Game of You", the hounding of Morpheus in "The Kindly Ones."

(Sandman #17.)

Gaiman never argues that these laws are just or fair. Quite the opposite. They ensnare; they trap.

("A Game of You" will be... complicated.)

If anything, Gaiman argues for the need to break out of these traps and cycles.

Even through death and destruction.

(Sandman #17.)

("A Game of You" will be... complicated.)

If anything, Gaiman argues for the need to break out of these traps and cycles.

Even through death and destruction.

(Sandman #17.)

Speaking of laws, traps and cycles...

Even in "Dream Country", Gaiman is playing the long game. "Brief Lives" and "The Kindly Ones" loom in the distance.

(Sandman #17.)

Even in "Dream Country", Gaiman is playing the long game. "Brief Lives" and "The Kindly Ones" loom in the distance.

(Sandman #17.)

Change is a key theme in "Sandman." Especially the acceptance of change. Especially Morpheus' acceptance of change within himself.

As with the last page of "Men of Good Fortune", "Calliope" makes it clear that Morpheus HAS changed. Even if he won't quite admit it.

(Sandman #17)

As with the last page of "Men of Good Fortune", "Calliope" makes it clear that Morpheus HAS changed. Even if he won't quite admit it.

(Sandman #17)

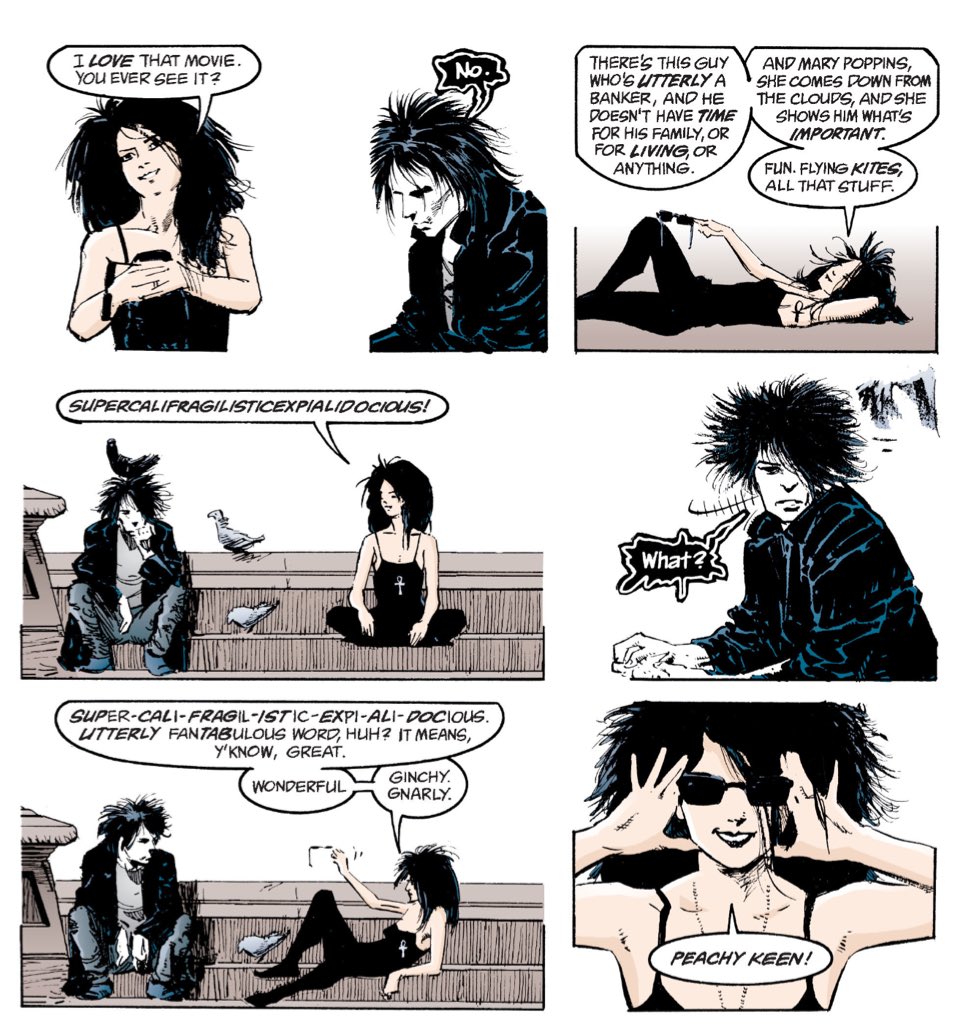

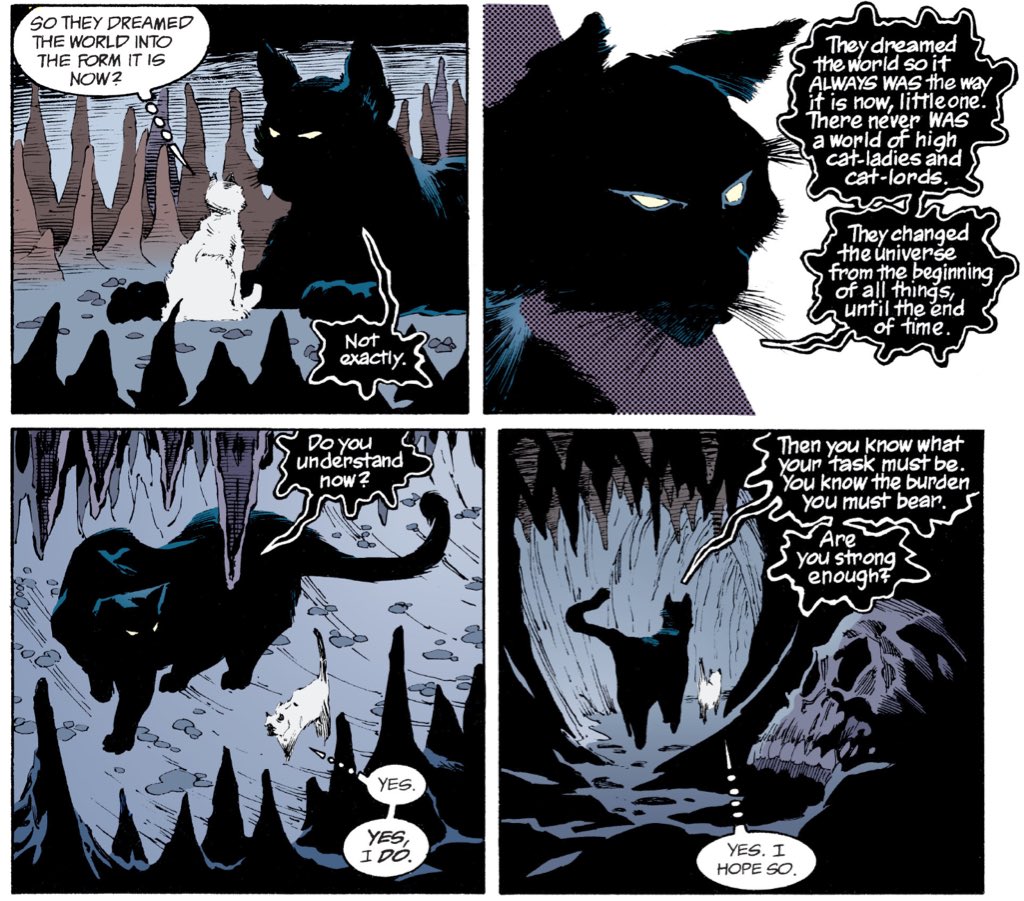

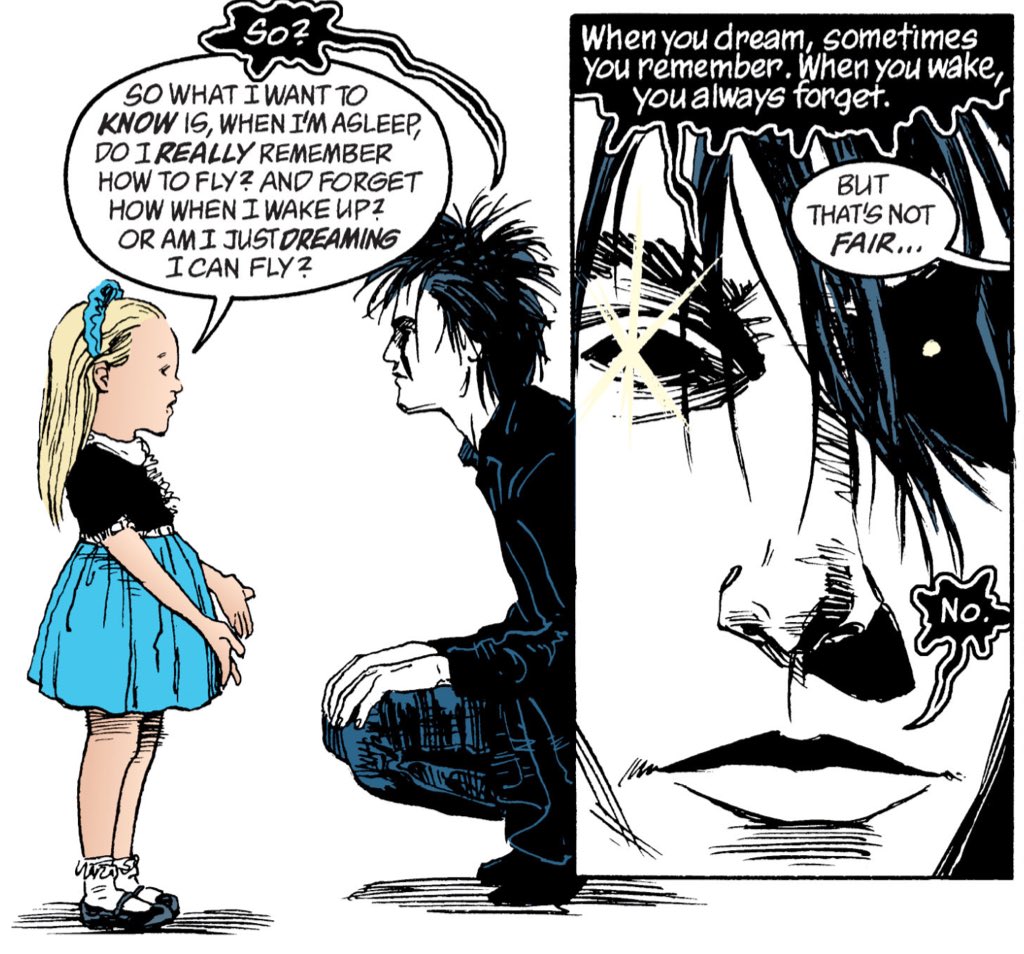

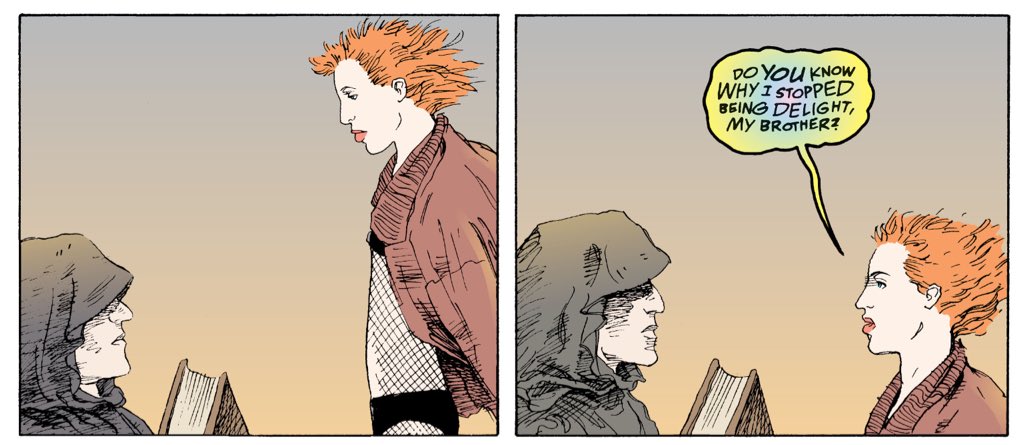

I have a massive soft spot for "A Dream of a Thousand Cats."

As a teenager, this would be the issue I'd share with people close to me, especially for people who didn't read comic books.

I mean it has everything. Cats! Stories! Heartbreak! Postmodernism!

(Sandman #18.)

As a teenager, this would be the issue I'd share with people close to me, especially for people who didn't read comic books.

I mean it has everything. Cats! Stories! Heartbreak! Postmodernism!

(Sandman #18.)

"A Dream of a Thousand Cats" would rank highly on my list of favourite issues of "Sandman."

If only because it's the perfect "done in one" Gaiman fairytale and also a great encapsulation of the series' themes.

(Sandman #18.)

If only because it's the perfect "done in one" Gaiman fairytale and also a great encapsulation of the series' themes.

(Sandman #18.)

"Justice? Justice is a delusion you will not find on this or any other sphere."

Once again, Gaiman distinguishes between the worlds is it is and any idea of fairness or decency.

The world is as it is, arbitrary and violent. With rules that are cruel.

(Sandman #18.)

Once again, Gaiman distinguishes between the worlds is it is and any idea of fairness or decency.

The world is as it is, arbitrary and violent. With rules that are cruel.

(Sandman #18.)

"Dreams shape the world."

The idea that the world is not objectively real, but a blank canvas unto which we project our reality, has certainly aged very well.

I mean, look at the world today.

(Sandman #18.)

The idea that the world is not objectively real, but a blank canvas unto which we project our reality, has certainly aged very well.

I mean, look at the world today.

(Sandman #18.)

“A Dream of a Thousand Cats” obviously has resonance beyond today’s mass delusions about Trumpism and Brexit.

Last time I read it, I thought of this (alleged) Karl Rove quote from a 2004 New York Time article about how dreams shape reality.

newsweek.com/national-sleep…

Last time I read it, I thought of this (alleged) Karl Rove quote from a 2004 New York Time article about how dreams shape reality.

newsweek.com/national-sleep…

One great thing about "A Dream of a Thousand Cats" is the ambiguity of it.

Is it true that humans changed the world with their dreams? Or is Morpheus simply offering hope to a lost soul?

Gaiman never answers that question, and the story's the stronger for it.

(Sandman #18.)

Is it true that humans changed the world with their dreams? Or is Morpheus simply offering hope to a lost soul?

Gaiman never answers that question, and the story's the stronger for it.

(Sandman #18.)

If it is a lie, it's possible to read the would-be cat messiah in "A Dream of a Thousand Cats" as another of Gaiman's beloved dreamers, characters who are remarkable precisely for their refusal to accept the world as it is.

See also: Joshua Norton.

(Sandman #18.)

See also: Joshua Norton.

(Sandman #18.)

"A Dream of a Thousand Cats" is tragic because of the cat messiah's dream is unattainable.

However, the fact that it can never be accomplished also perversely gives the dream some value; it is unfulfillable, and so it can be everlasting.

It's bittersweet.

(Sandman #18.)

However, the fact that it can never be accomplished also perversely gives the dream some value; it is unfulfillable, and so it can be everlasting.

It's bittersweet.

(Sandman #18.)

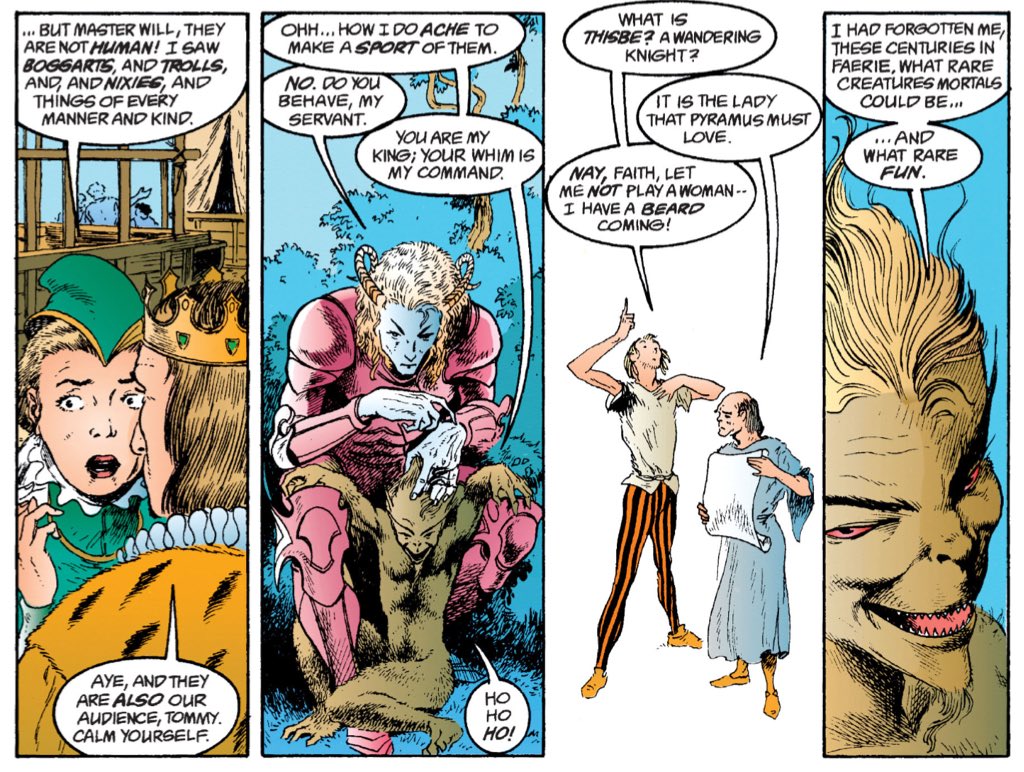

And so, the nineteenth issue.

"A Midsummer Night's Dream."

Nothing especially notable about this issue, then. Nothing at all.

(Sandman #19.)

"A Midsummer Night's Dream."

Nothing especially notable about this issue, then. Nothing at all.

(Sandman #19.)

“A Midsummer Night’s Dream” won the World Fantasy Award in 1991, becoming the first (and last) comic book to do so.

The organisation created a special category for comics afterwards, in a cynical ploy to keep them away from the “real” awards.

articles.chicagotribune.com/1991-12-20/fea…

The organisation created a special category for comics afterwards, in a cynical ploy to keep them away from the “real” awards.

articles.chicagotribune.com/1991-12-20/fea…

This type of awards ring-fencing is quite common, particularly with media and upon which the establishment look down.

That victory for “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” came a year before “Beauty and the Beast” surprised everyone by earning a “Best Picture” nomination.

That victory for “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” came a year before “Beauty and the Beast” surprised everyone by earning a “Best Picture” nomination.

“Beauty and the Beast” and “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” crashes pretty big glass ceilings for their media.

In a way that those awards bodies weren’t ready for.

I suspect that’s a large part of the appeal of “A Midsummer Night Dream.”

In a way that those awards bodies weren’t ready for.

I suspect that’s a large part of the appeal of “A Midsummer Night Dream.”

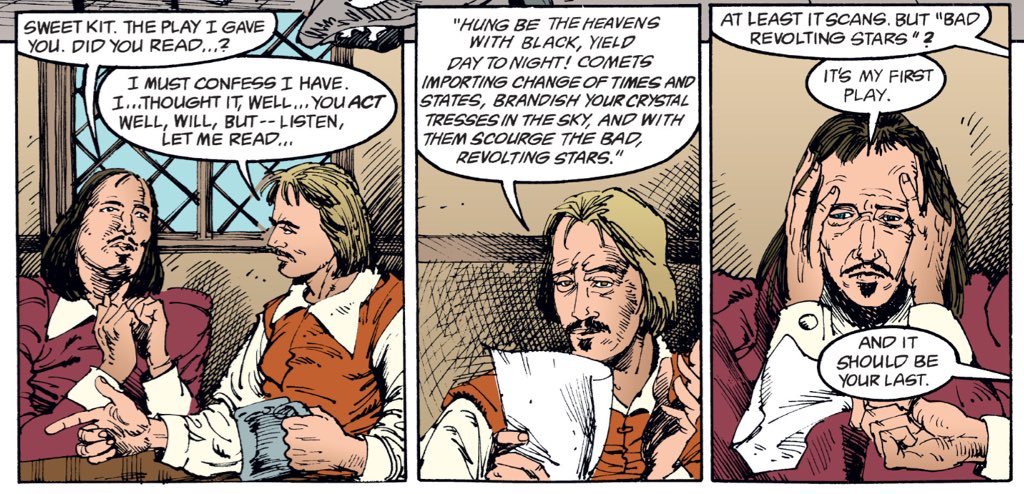

So, I should be upfront here. I like "A Midsummer Night's Dream" a lot, but also substantially less than most.

I much prefer, for example, the two stories either side of it. And many of the later stand-alones.

(Sandman #19.)

I much prefer, for example, the two stories either side of it. And many of the later stand-alones.

(Sandman #19.)

I suspect a large part of that is my fault.

As a teenager, and even now, I felt it was a lot easier to empathise with a cat that thought the world was broken or somebody horrified and anxious about their own body than to identify with William Shakespeare.

(Sandman #19.)

As a teenager, and even now, I felt it was a lot easier to empathise with a cat that thought the world was broken or somebody horrified and anxious about their own body than to identify with William Shakespeare.

(Sandman #19.)

I was also, and still am, a little wary about "A Midsummer Night's Dream."

It struck me as a variant on the "comics for grown-ups", flattering its reader with in-jokes about Shakespeare and seeming more consciously "literary" than the series had been.

(Sandman #19.)

It struck me as a variant on the "comics for grown-ups", flattering its reader with in-jokes about Shakespeare and seeming more consciously "literary" than the series had been.

(Sandman #19.)

I've softened on it with each re-read.

Mostly because it's clear that "A Misummer Night's Dream" means a lot to Gaiman.

Reading the script in the Absolute Edition also helped. Gaiman's tone was candour and trepidation, unsure if the story would work.

(Sandman #19.)

Mostly because it's clear that "A Misummer Night's Dream" means a lot to Gaiman.

Reading the script in the Absolute Edition also helped. Gaiman's tone was candour and trepidation, unsure if the story would work.

(Sandman #19.)

One of the most interesting aspects of "A Midsummer Night's Dream" and the last issue is the implicit connection Gaiman makes between himself and William Shakespeare.

That's a very tough comparison for any author to invite, but Gaiman does it well.

(Sandman #19.)

That's a very tough comparison for any author to invite, but Gaiman does it well.

(Sandman #19.)

A large part of that is down to Gaiman presenting Shakespeare as a man who doesn't understand his own gifts, who has been very lucky and is defined largely by how much he wants to be a good storyteller rather than by how much he succeeds.

(Sandman #19.)

(Sandman #19.)

Personal anecdote time!

When I was a kid, I did speech and drama. I don't know if I was good, but I was loud, I could enunciate, and I'd commit to the work.

At ten, this enough to win me some awards and got me bumped up a few grades to work with the older kids.

(Sandman #19.)

When I was a kid, I did speech and drama. I don't know if I was good, but I was loud, I could enunciate, and I'd commit to the work.

At ten, this enough to win me some awards and got me bumped up a few grades to work with the older kids.

(Sandman #19.)

The play that I did with them was "A Midsummer Night's Dream."

I played Bottom, because of course I did. I was loud, I could enunciate, and I would commit to the role.

One of my first crushes was my scene partner, four years old than me. And a much better actor.

(Sandman #19.)

I played Bottom, because of course I did. I was loud, I could enunciate, and I would commit to the role.

One of my first crushes was my scene partner, four years old than me. And a much better actor.

(Sandman #19.)

Anyway, that's my own little story.

I think about whenever I read "A Midsummer Night's Dream."

(Sandman #19.)

I think about whenever I read "A Midsummer Night's Dream."

(Sandman #19.)

Even here, there's darkness lurking.

Titania, queen of the fair folk, takes an interest in Hamnet, Shakespeare's son, who would die only a little while later.

Fairies were, of course, that class of story we once used to explain such horrible events.

(Sandman #19.)

Titania, queen of the fair folk, takes an interest in Hamnet, Shakespeare's son, who would die only a little while later.

Fairies were, of course, that class of story we once used to explain such horrible events.

(Sandman #19.)

This is what I mean when I talk about the Shakespeare-nerd in-jokes in "A Midsummer Night's Dream."

I like it a lot, but there are points when it becomes a bit clever-clever.

(Sandman #19.)

I like it a lot, but there are points when it becomes a bit clever-clever.

(Sandman #19.)

Nevertheless, there are moments when "A Midsummer Night's Dream" perfectly distils the themes of "Sandman."

Such as this great commentary from Puck on the power of fiction.

(Sandman #19.)

Such as this great commentary from Puck on the power of fiction.

(Sandman #19.)

This is the paradox of dreams and fiction. Often they are are more true than the facts.

(Sandman #19.)

(Sandman #19.)

"Façade" is one of those great "requiem for a fictional character" stories. Comics tend to do them very well, because there is such a long history to draw from and so many forgotten characters to use.

(Sandman #20.)

(Sandman #20.)

Even using an old forgotten DC character, Gaiman reconfigures "Element Girl" in terms of the mythology of "Sandman."

Another example of the gods' indifference to the lives that they destroyed. Another woman whose narrative is subsumed to that of a man.

(Sandman #20.)

Another example of the gods' indifference to the lives that they destroyed. Another woman whose narrative is subsumed to that of a man.

(Sandman #20.)

"I never asked for it."

In the end, "Façade" is about "Element Girl" asserting control over her narrative, control taken from her without her consent.

(Sandman #20.)

In the end, "Façade" is about "Element Girl" asserting control over her narrative, control taken from her without her consent.

(Sandman #20.)

Re-reading "Sandman", and accepting Gaiman's handling of trans themes is clumsy at points, I struck by how much of the series is people trapped in stories/lives/identities/bodies that don't reflect who they truly are.

It has aged well.

(Sandman #20.)

It has aged well.

(Sandman #20.)

One of the recurring themes of "Sandman" is that the older myths take longer to change than people do.

Morpheus; Lucifer; Ra.

But eventually even these myths change and grow.

It feels appropriate that "Façade" leads into "Season of Mists", where Lucifer changes.

(Sandman #20)

Morpheus; Lucifer; Ra.

But eventually even these myths change and grow.

It feels appropriate that "Façade" leads into "Season of Mists", where Lucifer changes.

(Sandman #20)

"Season of Mists" may be my favourite of the larger "Sandman" arcs.

It's just a beautiful story about rules, destiny, choice and freedom. The traps we set for ourselves and for others.

It also the first time the scope of the series truly comes into focus.

(Sandman #21.)

It's just a beautiful story about rules, destiny, choice and freedom. The traps we set for ourselves and for others.

It also the first time the scope of the series truly comes into focus.

(Sandman #21.)

Ah, Sandman's glorious recursion.

Playing on the theme of choice and rules, I love that Destiny calls a family meeting for no greater reason than because he read that he would call a meeting.

Setting in motion the entire plot of "Season of Mists."

(Sandman #21.)

Playing on the theme of choice and rules, I love that Destiny calls a family meeting for no greater reason than because he read that he would call a meeting.

Setting in motion the entire plot of "Season of Mists."

(Sandman #21.)

A subtle recurring motifs in "Sandman", and one rarely discussed, is the implication that Desire tends to draw us towards Death.

Desire's long game with Dream, suggested in "The Doll's House", is a great example of this.

Here, literalised with butterflies.

(Sandman #21.)

Desire's long game with Dream, suggested in "The Doll's House", is a great example of this.

Here, literalised with butterflies.

(Sandman #21.)

And, again, I love how Gaiman readily calls out Dream for being a monstrous self-centred bastard.

Gaiman never steers clear of the implications of Dream's pride and ego.

(Sandman #21.)

Gaiman never steers clear of the implications of Dream's pride and ego.

(Sandman #21.)

More foreshadowing, you say?

Destiny isn't the only Endless sibling looking through a book to his past and future.

(Sandman #22.)

Destiny isn't the only Endless sibling looking through a book to his past and future.

(Sandman #22.)

As much of a self-righteous ass as Morpheus can be, there are points at which his honour-before-reason approach is almost endearing.

There's a sense that he tries to be internally consistent, even as the series suggests he cannot prevent himself from changing.

(Sandman #22.)

There's a sense that he tries to be internally consistent, even as the series suggests he cannot prevent himself from changing.

(Sandman #22.)

The cosmology of "Sandman" is governed by rules. Indeed, the series repeatedly uses the metaphor of "play" to describe navigating these systems.

However, the theme is never as strong as it is in "Season of Mists", which is largely about rules and roles.

(Sandman #22.)

However, the theme is never as strong as it is in "Season of Mists", which is largely about rules and roles.

(Sandman #22.)

"Season of Mists" uses the "Morpheus visits Hob ahead of time, so you know this is serious" card, which the comic plays just a LITTLE too often over its seventy-odd issue run.

Hob sees Morpheus once a century, but somehow sees him a half-dozen times in a decade.

(Sandman #22.)

Hob sees Morpheus once a century, but somehow sees him a half-dozen times in a decade.

(Sandman #22.)

There's something kinda brilliant in how Gaiman sets up the idea of an epic no-holds-barred brawl between Lucifer and Morpheus...

... only to take it in a radically different (but brilliant) direction.

It recalls Steven Moffat's manner of plotting "Doctor Who."

(Sandman #22.)

... only to take it in a radically different (but brilliant) direction.

It recalls Steven Moffat's manner of plotting "Doctor Who."

(Sandman #22.)

And Gaiman sets up one of the big mysteries of "Sandman."

How much of what eventually happens is by Morpheus' own choice, conscious or otherwise? If it is unconscious, is it still a choice?

(Sandman #22.)

How much of what eventually happens is by Morpheus' own choice, conscious or otherwise? If it is unconscious, is it still a choice?

(Sandman #22.)

Obviously homaging Milton, Gaiman's use of Lucifer in "Season of Mists" is quite brilliant.

Lucifer is an angel who thought he was rebelling, but was ultimately just fulfilling a role in which he'd been cast.

Finally, he decides to break free of that role.

(Sandman #23.)

Lucifer is an angel who thought he was rebelling, but was ultimately just fulfilling a role in which he'd been cast.

Finally, he decides to break free of that role.

(Sandman #23.)

Indeed, one of the cleverer ideas of "Seasons of Mists" is that human souls trap themselves in hell, consigning themselves.

That they are free to walk away, if they choose to, if they can bring themselves to break free of the role in which they cast themselves.

(Sandman #23.)

That they are free to walk away, if they choose to, if they can bring themselves to break free of the role in which they cast themselves.

(Sandman #23.)

I love Gaiman's subversion of the prospect of an epic battle between Morpheus and Lucifer, denying his audience that punch-'em up action, in favour of something more reflective and contemplative.

(Sandman #23.)

(Sandman #23.)

There's something beautiful in the way that Lucifer declines to throw down with Morpheus directly. It's heavily implied that Lucifer could destroy Morpheus with a thought.

Instead, Lucifer tries to defeat Morpheus by casting him in a role, trapping him in a story.

(Sandman #23)

Instead, Lucifer tries to defeat Morpheus by casting him in a role, trapping him in a story.

(Sandman #23)

"What do you WANT to do with it?"

"I do not know."

The real beauty of Lucifer's revenge on Morpheus.

It forces him to make a choice without a binding system of rules in place to guide that decision.

Morpheus is very powerful, but rendered impotent by choice.

(Sandman #24.)

"I do not know."

The real beauty of Lucifer's revenge on Morpheus.

It forces him to make a choice without a binding system of rules in place to guide that decision.

Morpheus is very powerful, but rendered impotent by choice.

(Sandman #24.)

One of the issues with adapting Sandman to film (and possibly even television) is the risk of losing all the glorious one-shots along the way.

It'd really need a format like Japanese anime, a half-hour animation in which each of seventy-odd episodes was a chapter.

(Sandman #25)

It'd really need a format like Japanese anime, a half-hour animation in which each of seventy-odd episodes was a chapter.

(Sandman #25)

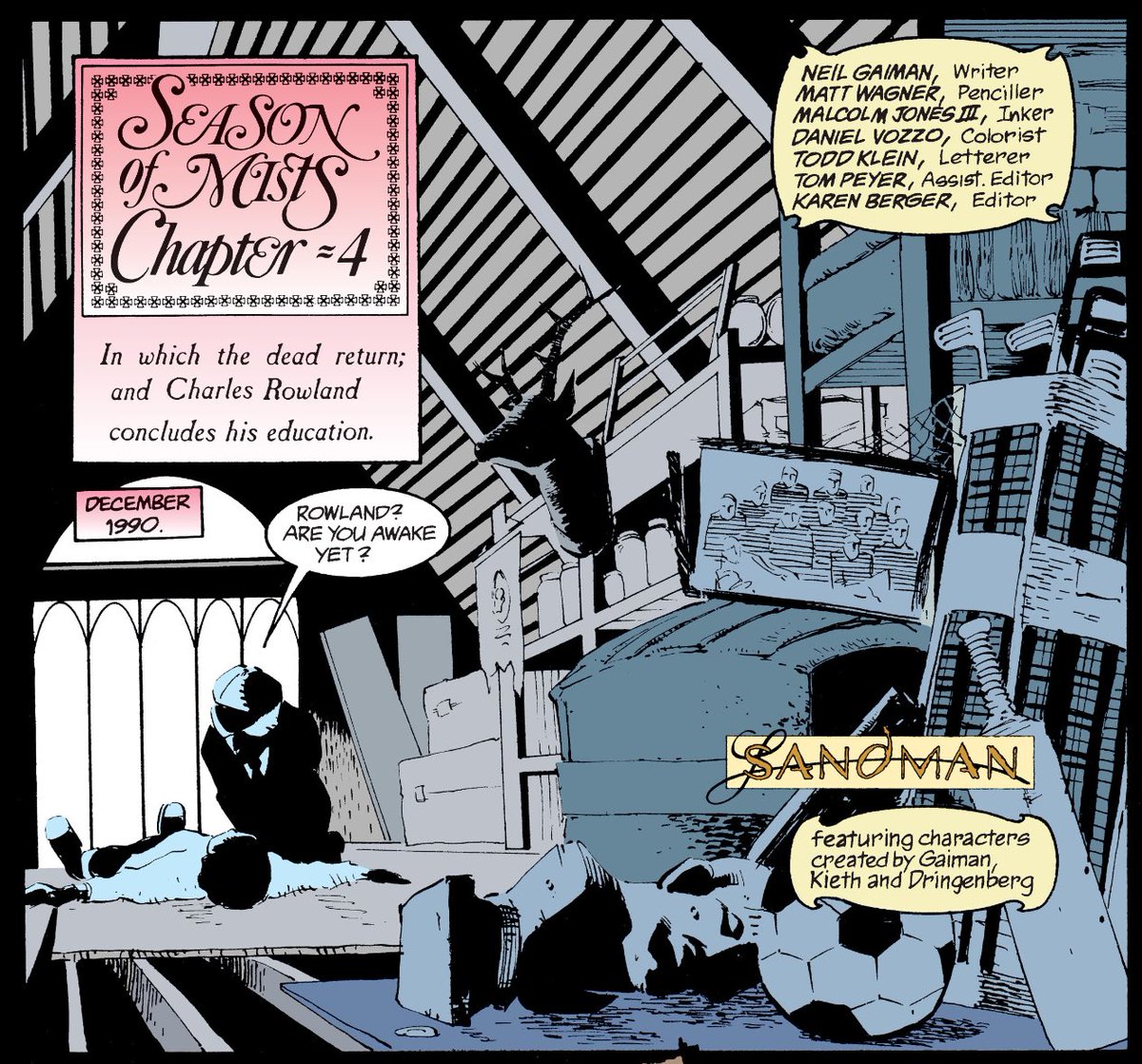

Is the story of Charles Rowland essential to "Season of Mists" from a plotting perspective? No. It'd be one of this things cut from any adaptation.

Which is a shame, because (a.) it's great and (b.) it's essential Sandman.

(Sandman #25.)

Which is a shame, because (a.) it's great and (b.) it's essential Sandman.

(Sandman #25.)

The chapter on Charles Rowland distils a key theme of "Season of Mists" down to an inversion of Satre.

Hell is not so much other people as it is ourselves; our unwillingness to change destructive patterns of behaviour, and instead perpetuate them.

(Sandman #25.)

Hell is not so much other people as it is ourselves; our unwillingness to change destructive patterns of behaviour, and instead perpetuate them.

(Sandman #25.)

This gets at the endearing humanism of "Sandman."

We don't have to be stuck in these destructive patterns of behaviour. We can leave them behind. We can change.

"You don't have to stay anywhere forever."

(Sandman #25.)

We don't have to be stuck in these destructive patterns of behaviour. We can leave them behind. We can change.

"You don't have to stay anywhere forever."

(Sandman #25.)

As above, so below.

Rowland and Paine leaving the gates of the boarding school mirrors Lucifer leaving the Gates of Hell.

"Seasons of Mists" suggests you can walk away from horrific systems and cycles.

Setting up the tragedy in how Morpheus can't QUITE do it.

(Sandman #25.)

Rowland and Paine leaving the gates of the boarding school mirrors Lucifer leaving the Gates of Hell.

"Seasons of Mists" suggests you can walk away from horrific systems and cycles.

Setting up the tragedy in how Morpheus can't QUITE do it.

(Sandman #25.)

It's weird to describe a story about two dead kids at a creepy boarding school as "upbeat."

But here we are.

There's a great big world out there, if you're willing to grab it.

(Sandman #25.)

But here we are.

There's a great big world out there, if you're willing to grab it.

(Sandman #25.)

One of the nicer "minor character callbacks" across the length and breadth of the series.

I hope they got a happy ending.

(Sandman #26/71.)

I hope they got a happy ending.

(Sandman #26/71.)

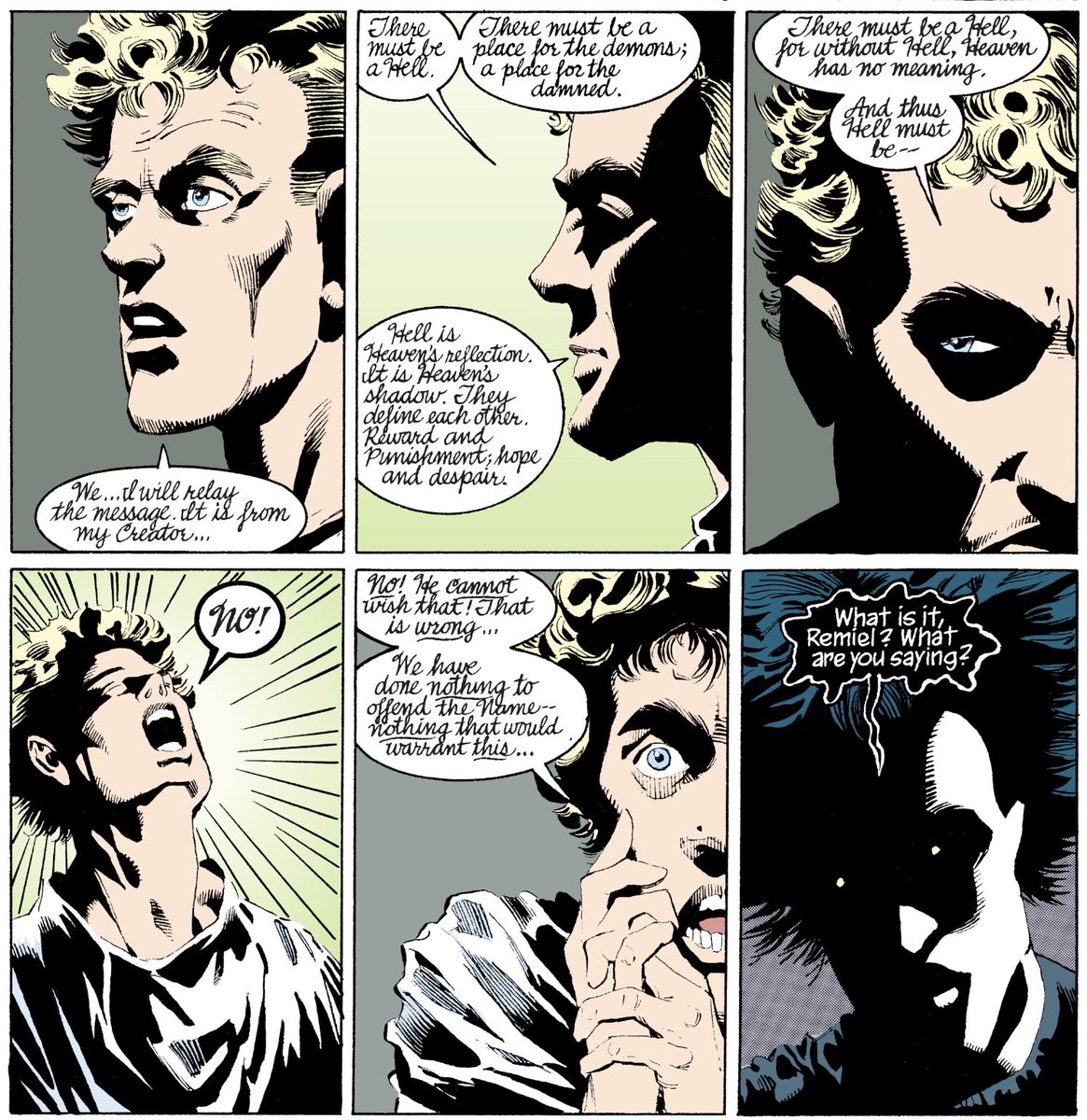

In keeping with theme of rules and systems in "Season of Mists", and the idea that these are arbitrary and unfair, the resolution makes a great deal of sense.

God decides there must be a Hell, and assigns Remiel and Duma to it, despite their good work.

(Sandman #27.)

God decides there must be a Hell, and assigns Remiel and Duma to it, despite their good work.

(Sandman #27.)

Remiel and Duma he no choice, no free will, no agency.

That somehow makes their fate especially tragic.

(Sandman #27.)

That somehow makes their fate especially tragic.

(Sandman #27.)

A nice touch: Morpheus spends most of "Season of Mists" trying to avoid making a choice.

Then God comes down at the end of the story and makes the choice for him.

(Sandman #27.)

Then God comes down at the end of the story and makes the choice for him.

(Sandman #27.)

In keeping with the theme of systems and codes running through the arc and series, some excellent rules-lawyering from Morpheus here, to protect Nada.

(Sandman #27.)

(Sandman #27.)

And so, in the coda of "Season of Mists", we come to the point.

Morpheus can never surrender his responsibilities or accept that he has changed as Lucifer has done at the start of the arc.

He can never deal himself out. At least not in the way Lucifer does.

(Sandman #28.)

Morpheus can never surrender his responsibilities or accept that he has changed as Lucifer has done at the start of the arc.

He can never deal himself out. At least not in the way Lucifer does.

(Sandman #28.)

Speaking of foreshadowing.

With four panels, Gaiman teases a mystery that is framed forty issues down the line, and which is still debated among "Sandman" fans.

Does Loki ever settle his debt to Morpheus?

(Sandman #28.)

With four panels, Gaiman teases a mystery that is framed forty issues down the line, and which is still debated among "Sandman" fans.

Does Loki ever settle his debt to Morpheus?

(Sandman #28.)

The ending of "Season of Mists" is shaded by how one reads Loki's motivations, and who one believes his employer to be, in "The Kindly Ones."

Is Morpheus' mercy to the Trickster God, rooted in his own experiences, an act of dramatic irony or grand tragedy?

(Sandman #28.)

Is Morpheus' mercy to the Trickster God, rooted in his own experiences, an act of dramatic irony or grand tragedy?

(Sandman #28.)

Gaiman explicitly acknowledges one of the grander paradoxes of "Season of Mists."

The story repeatedly stresses that the damned are ultimately in hell by their own choice, that they can free themselves.

But it also blames Morpheus for trapping Nada in hell.

(Sandman #28.)

The story repeatedly stresses that the damned are ultimately in hell by their own choice, that they can free themselves.

But it also blames Morpheus for trapping Nada in hell.

(Sandman #28.)

I haven't acknowledged Gaiman's artistic collaborators as much as I should have.

The heart of "Season of Mists" is illustrated by Kelley Jones, who also did a lot of "Dream Country."

Jones has that wonderful grotesque atmospheric gothic style. Beautiful stuff.

(Sandman #27.)

The heart of "Season of Mists" is illustrated by Kelley Jones, who also did a lot of "Dream Country."

Jones has that wonderful grotesque atmospheric gothic style. Beautiful stuff.

(Sandman #27.)

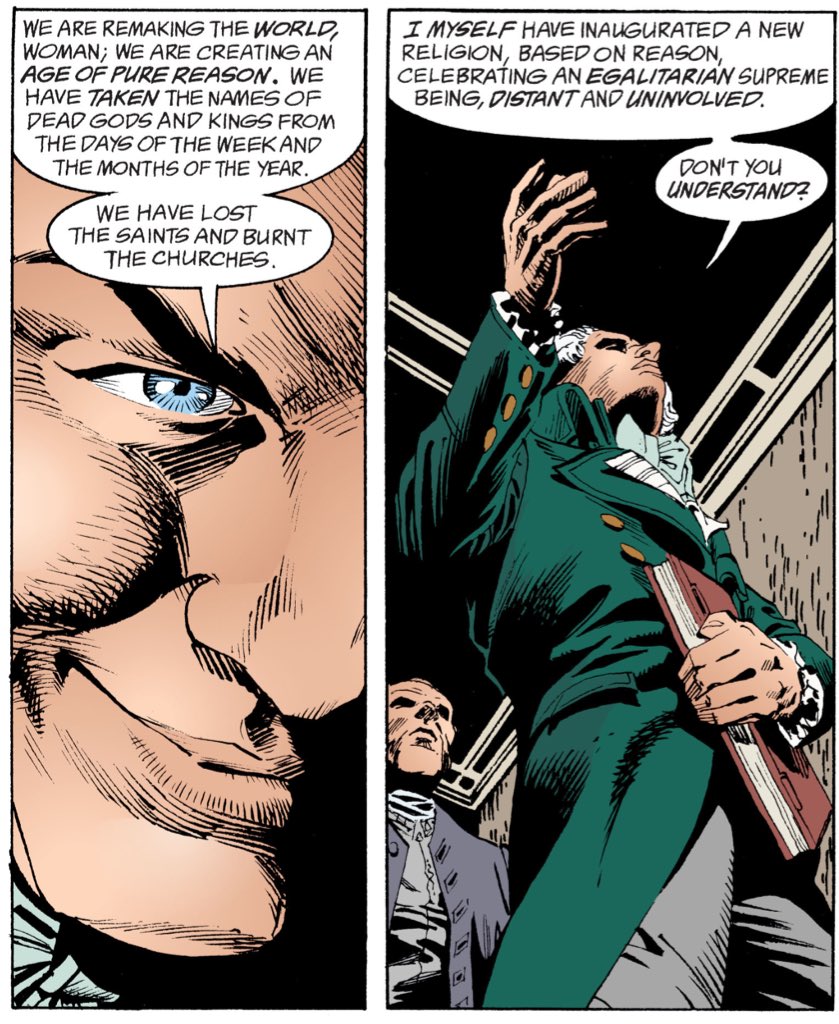

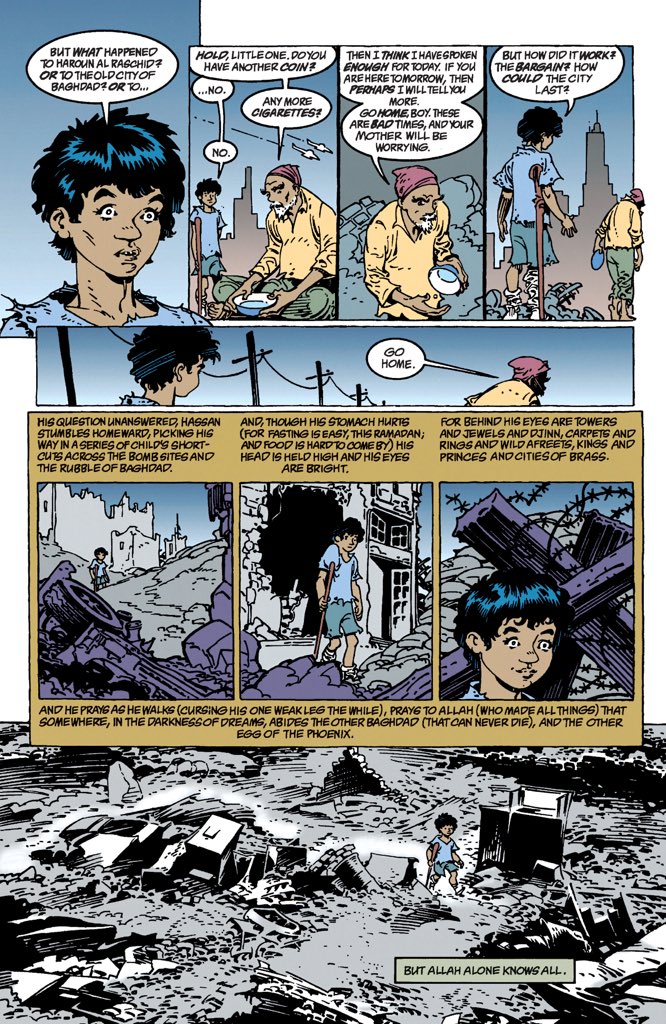

After "Season of Mists", another set of short stories. "Distant Mirrors."

Much like "Dream Country " transitioned thematically into "Season of Mists" with an emphasis on rules and systems, "Distant Mirrors" transitions out with a recurring motif of rulers/kings.

(Sandman #29.)

Much like "Dream Country " transitioned thematically into "Season of Mists" with an emphasis on rules and systems, "Distant Mirrors" transitions out with a recurring motif of rulers/kings.

(Sandman #29.)

As the title implies, "Distant Mirrors" is populated with warped reflections of Morpheus.

Rulers and kings overseeing dreams as much as kingdoms. Robespierre, Augustus Caesar, Emperor Joshua Norton I.

(Sandman #29.)

Rulers and kings overseeing dreams as much as kingdoms. Robespierre, Augustus Caesar, Emperor Joshua Norton I.

(Sandman #29.)

Robespierre in particular is presented as a mad visionary king.

He plots to destroy the head of Orpheus to usher in an age of rationality, but he really just wants to assert his own authority and dominion over the dreams and imagination of man.

(Sandman #29.)

He plots to destroy the head of Orpheus to usher in an age of rationality, but he really just wants to assert his own authority and dominion over the dreams and imagination of man.

(Sandman #29.)

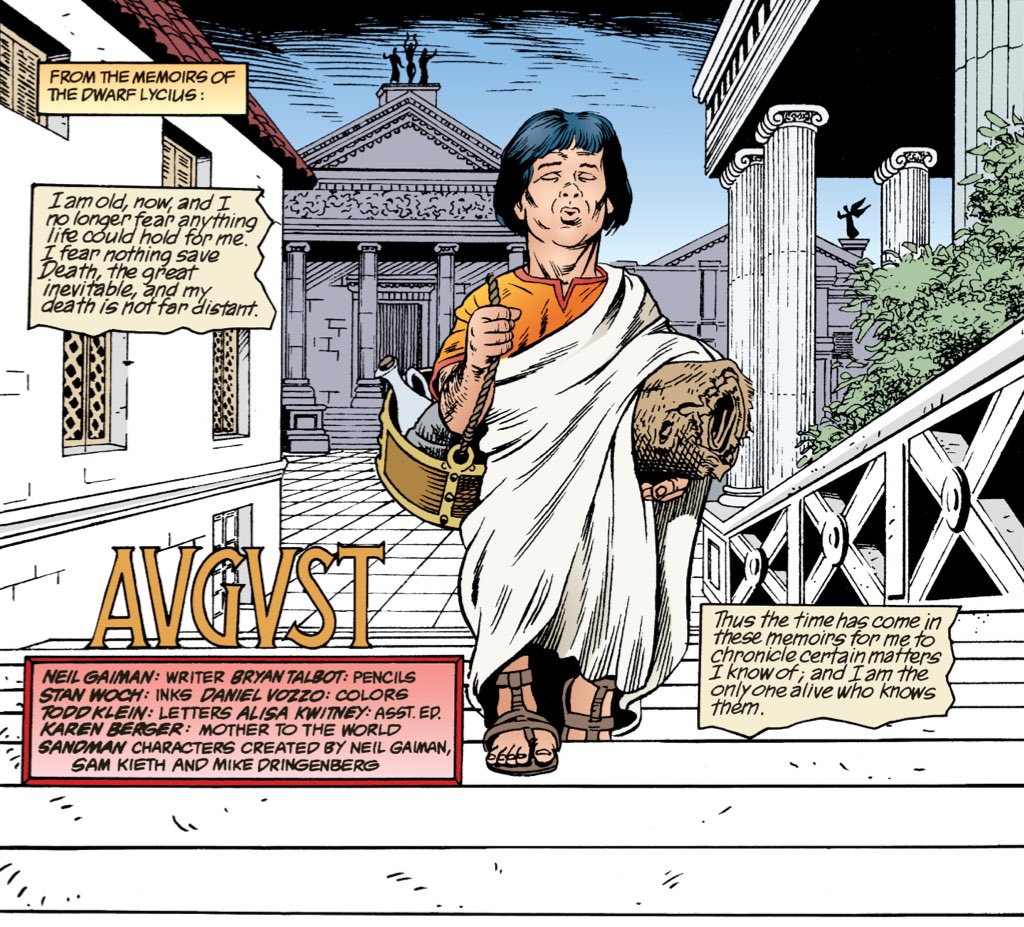

In dealing with historical figures who appear in "Sandman", Gaiman has been candid about his "print the legend" approach.

For example "August" is rooted in the idea that Augustus Caesar collapsed to Roman Empire to avenge himself on his abusive uncle Julius.

(Sandman #30.)

For example "August" is rooted in the idea that Augustus Caesar collapsed to Roman Empire to avenge himself on his abusive uncle Julius.

(Sandman #30.)

Of course these claims are all gossip and hearsay, traced back to Mark Anthony who had an obvious motivation to discredit Augustus’ claim to the Empire.

They are denied by historian Suetonius.

So there’s no way to know for sure what happened.

reddit.com/r/AskHistorian…

They are denied by historian Suetonius.

So there’s no way to know for sure what happened.

reddit.com/r/AskHistorian…

To be fair, this fits in the world of "Sandman."

"Sandman is more firmly engaged with the truth revealed in stories than in the truth revealed by facts.

As such, it makes sense that Gaiman should treat these figures as stories and narratives.

(Sandman #30.)

"Sandman is more firmly engaged with the truth revealed in stories than in the truth revealed by facts.

As such, it makes sense that Gaiman should treat these figures as stories and narratives.

(Sandman #30.)

As with "Dream Country", the stories that make up "Distant Mirrors" echo and refract key themes of the series as a whole.

"Family is the foundation stone upon which the empire is built."

What is "Sandman" but the story of an emperor and his family?

(Sandman #30.)

"Family is the foundation stone upon which the empire is built."

What is "Sandman" but the story of an emperor and his family?

(Sandman #30.)

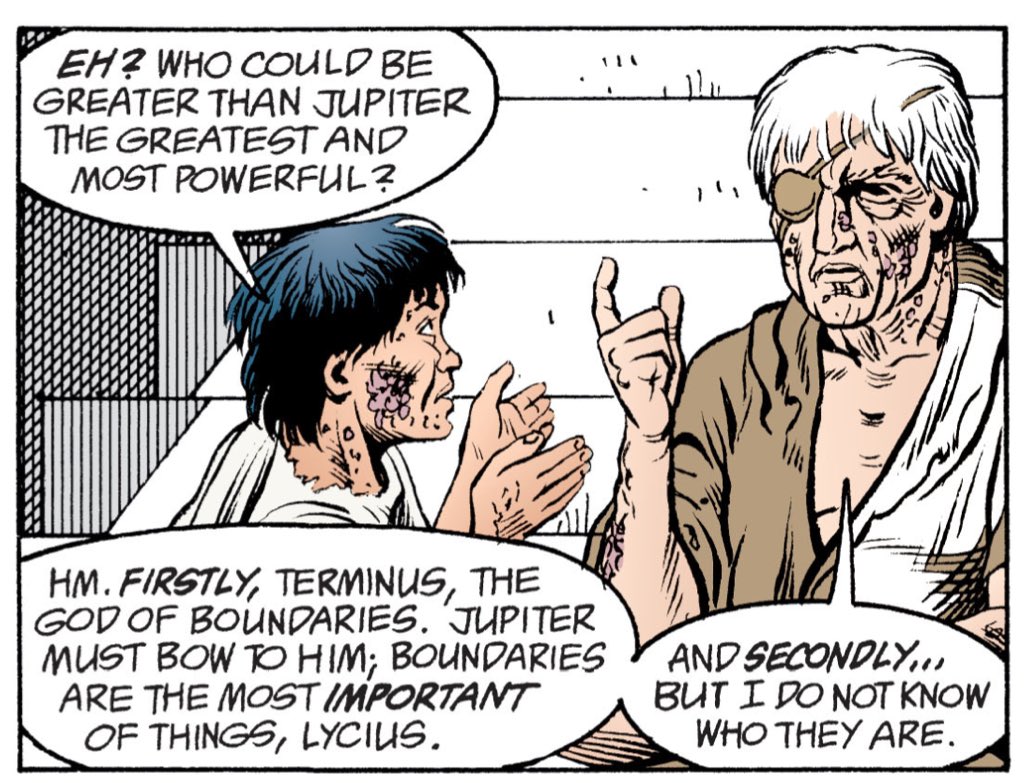

In keeping with this idea of thematic resonance, "August" returns to a core theme of "Sandman", that even the most powerful of individuals are trapped by rules and systems.

Boundaries, as it were.

(Sandman #30.)

Boundaries, as it were.

(Sandman #30.)

Of course Morpheus, a character defined by his respect for systems and rules, is a close personal friend of the god "who walks the boundaries."

(Sandman #30.)

(Sandman #30.)

Hm.

A great and powerful leader who carefully and meticulously engineers the collapse of his own kingdom when the gods aren't watching? And nobody realises it?

My, whatever could Gaiman possibly be foreshadowing?

(Sandman #30.)

A great and powerful leader who carefully and meticulously engineers the collapse of his own kingdom when the gods aren't watching? And nobody realises it?

My, whatever could Gaiman possibly be foreshadowing?

(Sandman #30.)

I'm pretty agnostic on "Thermidor" and "August" as standalone stories.

But "Three Septembers and a January" is one of the best single-issue stories in the entirety of "Sandman."

Beautiful, moving stuff about the power of dreams.

(Sandman #31.)

But "Three Septembers and a January" is one of the best single-issue stories in the entirety of "Sandman."

Beautiful, moving stuff about the power of dreams.

(Sandman #31.)

"Three Septembers and a January" is one of the moving and humanist things that Gaiman has ever written.

It is a loving ode to somebody that most societies would marginalise and mock, a fundamentally decent man with a skewed way of looking at the world.

(Sandman #31.)

It is a loving ode to somebody that most societies would marginalise and mock, a fundamentally decent man with a skewed way of looking at the world.

(Sandman #31.)

I mean, c'mon.

Only a monster wouldn't be moved by Gaiman's account of Joshua Norton I, Emperor of the United States.

(Sandman #31.)

Only a monster wouldn't be moved by Gaiman's account of Joshua Norton I, Emperor of the United States.

(Sandman #31.)

While telling this beautiful done-in-one story, "Three Septembers and a January" also returns to the theme of "Distant Mirrors", the importance of rulers and leaders.

The Dreaming having been without a ruler for decades, and Hell abandoned by Lucifer.

(Sandman #31.)

The Dreaming having been without a ruler for decades, and Hell abandoned by Lucifer.

(Sandman #31.)

Also, did somebody say "foreshadowing"?

Although, Desire already made its play back in "The Doll's House", as with the mirroring of Dream with Augustus in "August", there's a sense Gaiman is already stoking what remains (to this day) the series' biggest mystery.

(Sandman #31.)

Although, Desire already made its play back in "The Doll's House", as with the mirroring of Dream with Augustus in "August", there's a sense Gaiman is already stoking what remains (to this day) the series' biggest mystery.

(Sandman #31.)

Also, fun fact about “Three Septembers and a January”: the “King of Pain” was a real figure from nineteenth century San Francisco.

Here’s his obituary from the Daily Alta California, 19th May 1871.

Here’s his obituary from the Daily Alta California, 19th May 1871.

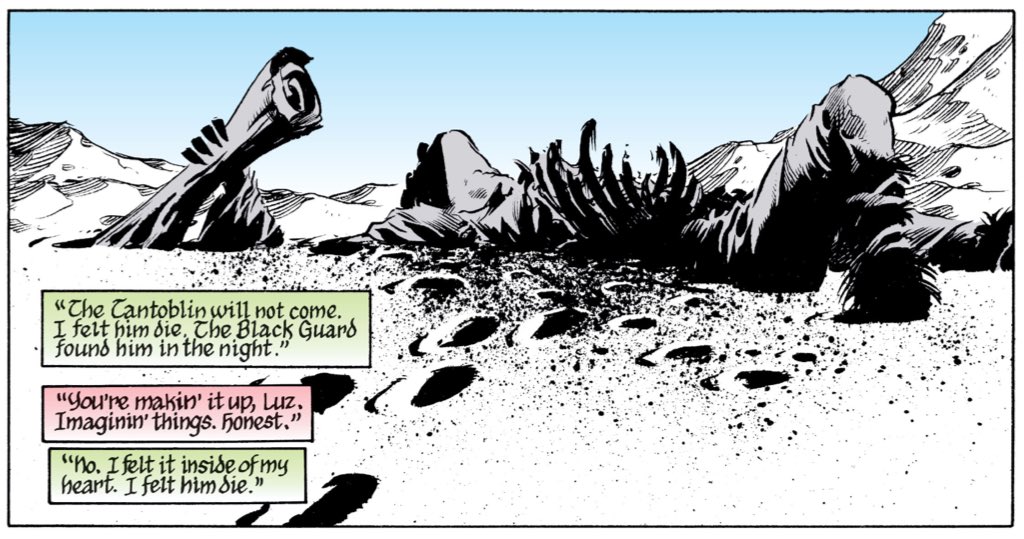

Considering that "Somg of Orpheus" was published right before "Game of You", this is some nice foreshadowing.

Hint, hint.

(Sandman Special #1.)

Hint, hint.

(Sandman Special #1.)

And, again, the importance of rules and systems in "Sandman", coupled with the faint suggestion that the Furies might hold a grudge against Orpheus.

And MAAAAAAYBE his family too?

(Sandman Special #1.)

And MAAAAAAYBE his family too?

(Sandman Special #1.)

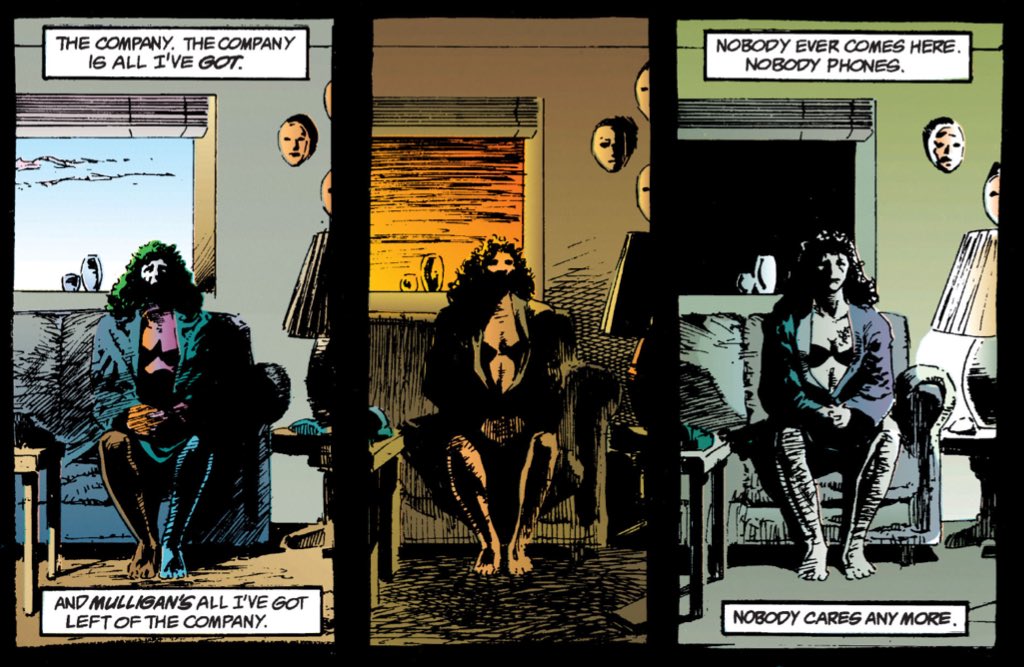

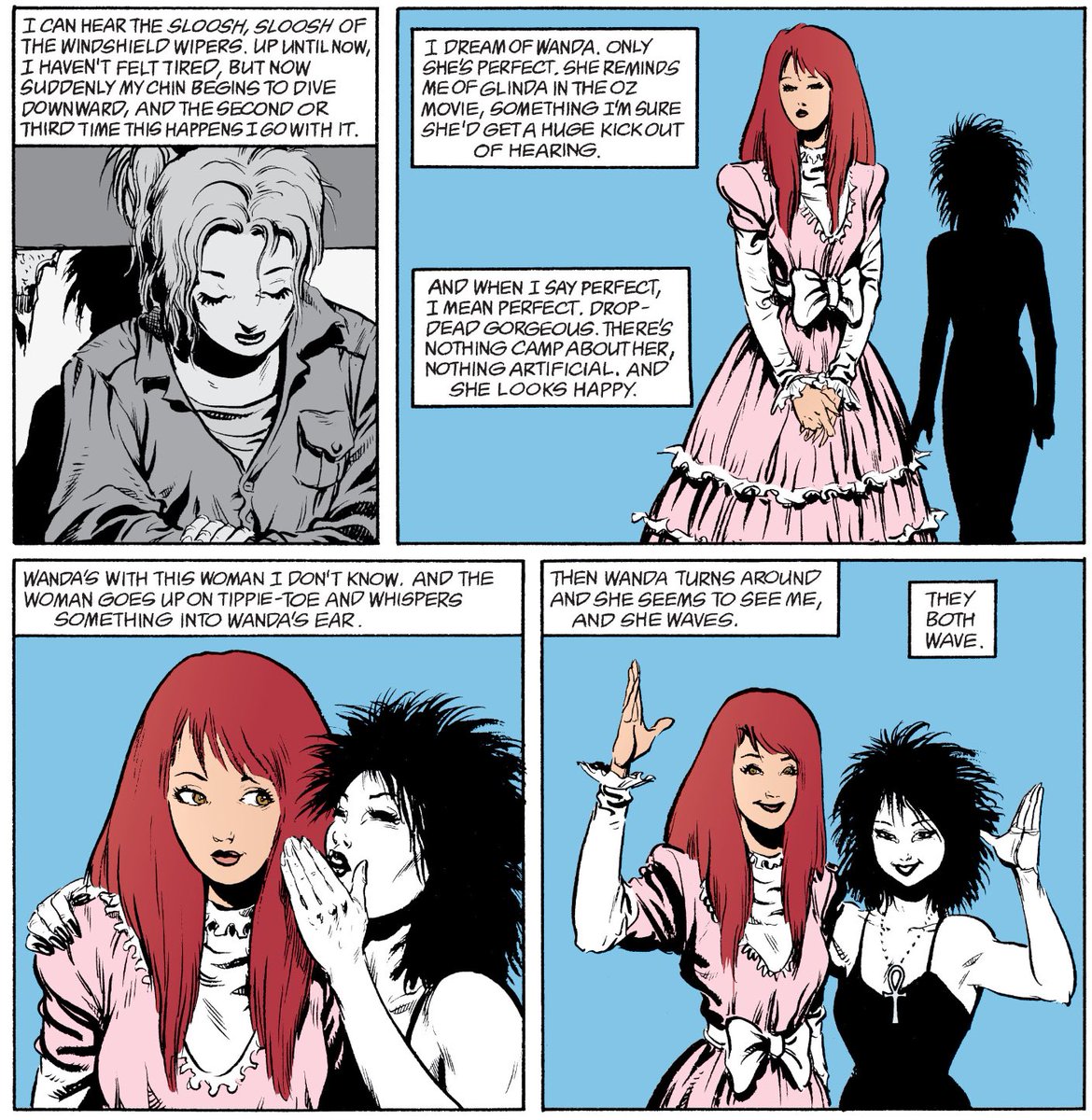

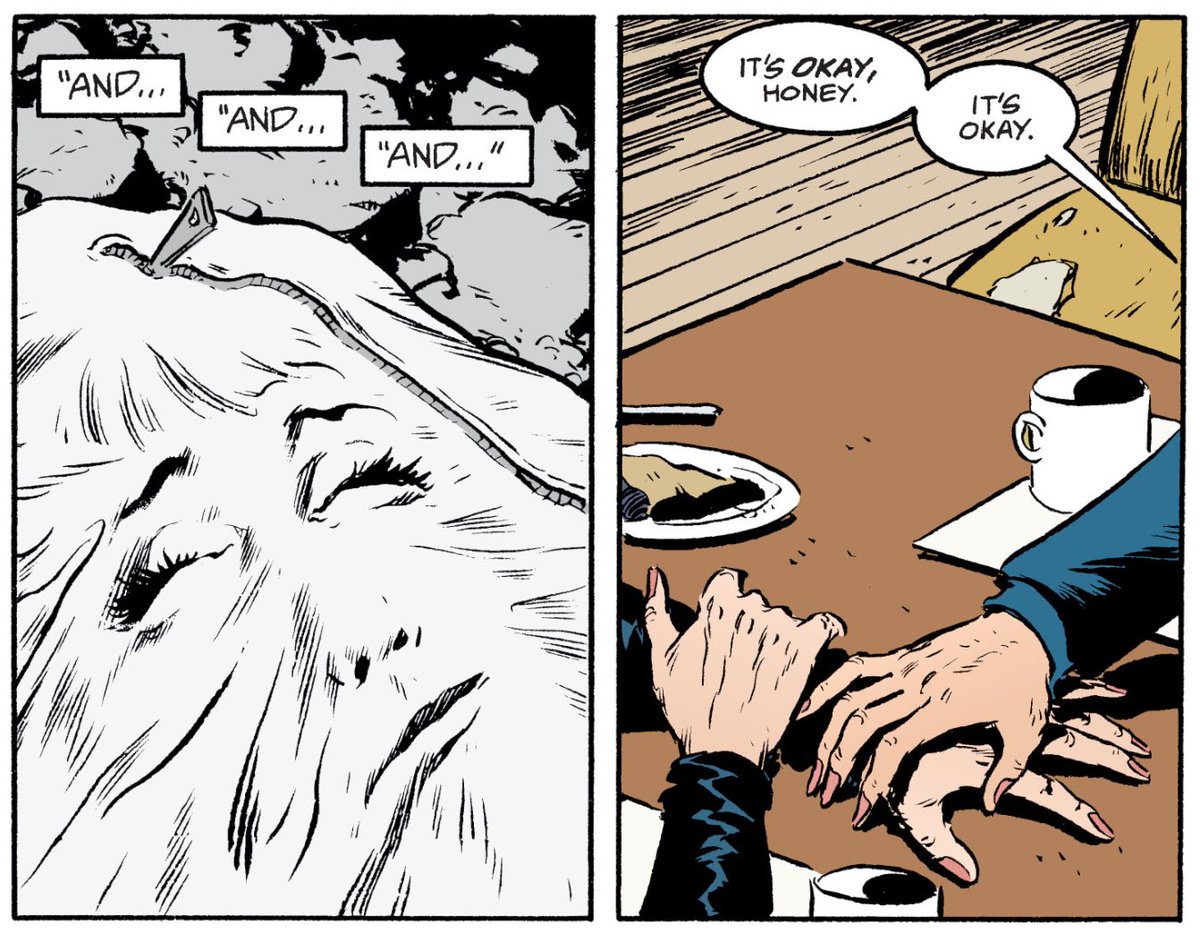

So, we’re on to “A Game of You.”

Which is, and always has been, one of my favourite “Sandman” arcs.

However, it has some controversy hanging over it, with allegations of transphobia against Wanda.

Here’s a good summary of the arguments.

web.archive.org/web/2015010221…

Which is, and always has been, one of my favourite “Sandman” arcs.

However, it has some controversy hanging over it, with allegations of transphobia against Wanda.