Here’s a piece that David Romer and I just wrote for the latest CSWEP newsletter, which we think contains some useful insights for those seeking to make economics a more diverse place.

Begins on p.7, here: aeaweb.org/content/file?i…

Lemme expand a bit on what we found...

Begins on p.7, here: aeaweb.org/content/file?i…

Lemme expand a bit on what we found...

When we took over as editors of the Brookings Papers, we made a conscious decision to try to include more women economists on the program. You can think of this as something of an experiment, and so our note is our attempt to report on the results.

By one measure, we succeeded. The number of women who published in the @BrookingsEcon Papers more than doubled, to a share that somewhat exceeds the share of women in “top twenty” economics departments.

I know you love diff-in-diffs, so Everyone loves diffs-in-diffs, so the it’s worth comparing the share of women writing for #BPEA both before and after our experiment, and relative to comparable conference and journals.

A chart is worth a thousand words:

A chart is worth a thousand words:

The most important thing that helped, I think, was just trying to be gender aware. Trying to avoid conscious discrimination under the presumption that implicit bias only afflicts the judgment of others is a recipe for gross gender imbalance.

Let’s be concrete. In our experience, the following practices helped:

- We gave ourselves quantitative guidelines

- We interpreted these as a floor, not a target

- We pushed each other to do better

- We broadened the set of fields we would publish

- We had institutional support

- We gave ourselves quantitative guidelines

- We interpreted these as a floor, not a target

- We pushed each other to do better

- We broadened the set of fields we would publish

- We had institutional support

Other well-intentioned changes didn’t move the needle:

- Our more formally structured call for papers didn’t lead to a bunch more submissions from women

- Recruiting the top women in the profession simply supported work that was already going to get published

- Our more formally structured call for papers didn’t lead to a bunch more submissions from women

- Recruiting the top women in the profession simply supported work that was already going to get published

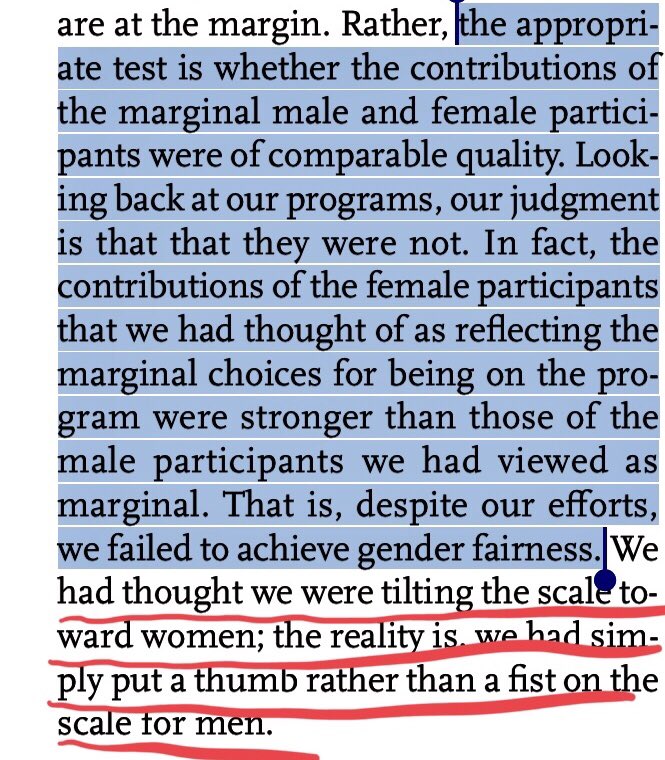

But the bigger picture is that we failed. The relevant question is whether *at the margin* the marginal female participant contributed more than the marginal man. In our judgment, the answer was a resounding yes.

“We had thought we were tilting the scale toward women; the reality is, we had simply put a thumb rather than a fist on the scale for men.”

That was a helluva lesson for us to learn. And we’re sure that it has implications for other efforts to improve gender equity.

That was a helluva lesson for us to learn. And we’re sure that it has implications for other efforts to improve gender equity.

We wish that we could report on our efforts to improve the underrepresentation of African-Americans and other marginalized voices. But the underrepresentation of some groups is so severe that in reality, we would be reporting anecdotes disguised as data.

What I learned: Even when you think you’re working as hard as you can to redress imbalances, it’s quite possible that you’re still not doing enough. [/fin]

Also, my friend Karen Pence (not that Karen Pence, the economist, Karen Pence...) has a wonderful article with Daniel Covitz, outlining the Fed’s efforts to create a more diverse and inclusive workforce.

See p.4, here: aeaweb.org/content/file?i…

See p.4, here: aeaweb.org/content/file?i…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh