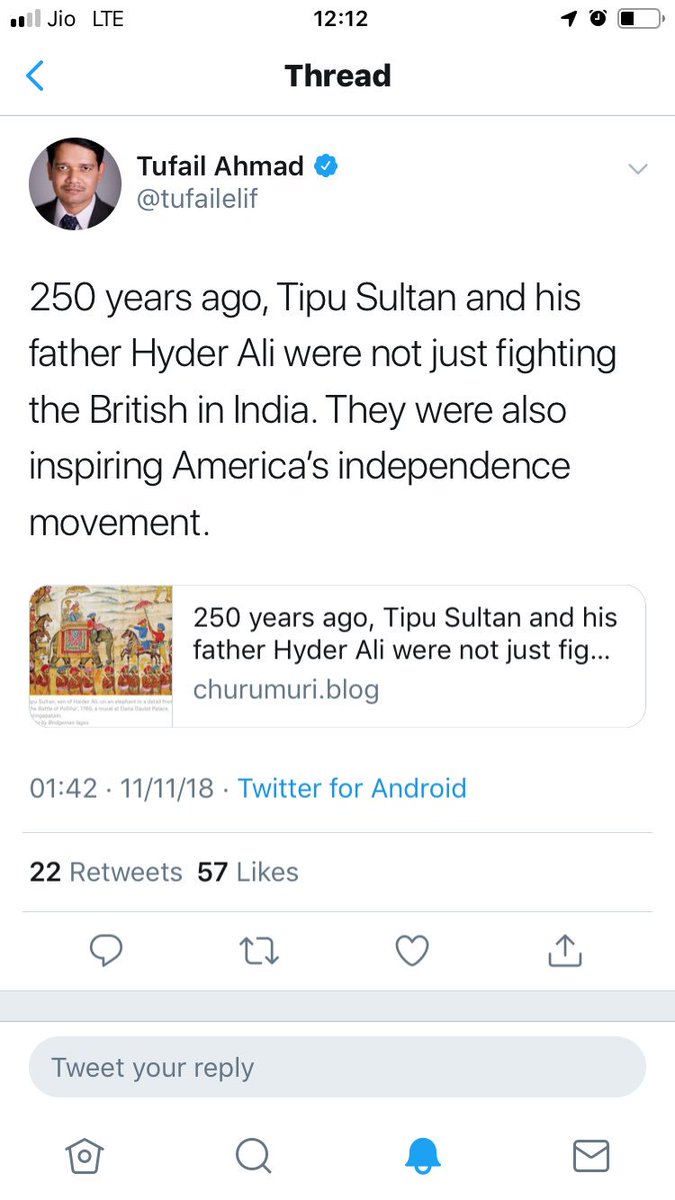

Sadar Pranam to the God within you @tufailelif ji. I’m sorry but Tipu Sultan & his father weren’t actually fighting British. In thread below, I explain how not👇🏼.You may respond in your full capacity. Cc @Sanjay_Dixit @vivekagnihotri @ippatel

https://twitter.com/tufailelif/status/1061350918120267776

2/n There are enough writers who indulge in false glorification of Tipu, thru secular & tolerant make up they have applied to his face.Kavesh Yazdani in one such subtle whitewasher.

In an article,Yazdani says(3n onwards. I attach SC of @tufailelif tweet(he has already blockd me)

In an article,Yazdani says(3n onwards. I attach SC of @tufailelif tweet(he has already blockd me)

3/n “Tipu was also aware of American War of Independence & reportedly uttered, 'Every blow that is struck in the cause of American liberty throughout the world,in France,India & elsewhere & so long as a single insolent & savage tyrant remains, the struggle shall continue.'

4/n Reference for 3/n

Click link, Volume 38, Issue 02, August 2014, page 106.)

Yazdani's reference to this statement given in end note 62 is “Kausar, Secret Correspondence of Tipu Sultan, 306.” academia.edu/8701791/Haidar…

Click link, Volume 38, Issue 02, August 2014, page 106.)

Yazdani's reference to this statement given in end note 62 is “Kausar, Secret Correspondence of Tipu Sultan, 306.” academia.edu/8701791/Haidar…

5/n So Now let’s look up Kabir Kausar's book cited by Yazdani. The statement, indeed, was there. It is in Appendix F entitled “Tipu Sultan's Observations (Compiled from fifth edition of 'The Sword of Tipu Sultan' by Bhagwan S. Gidwani).” Link to book archive.org/stream/in.erne…

6/n (Secret Correspondence of Tipu Sultan, page 303.) The first sentence in the appendix is: “The quotations given below show different facets of Tipu's philosophy and character.” Then the quotations were given under different headings.

7/n In the fourth section entitled “Tipu's Views on the American Declaration of Independence” we can find the following quotation:

8/n “Every blow that was struck in the cause of American liberty throughout the world, in France, India and elsewhere and so long as a single insolent and savage tyrant remains, the struggle shall continue. (p. 210).” (Secret Correspondence of Tipu Sultan, page 306.)

9/n There is nothing secret about the correspondence of Tipu given in the book. Why Kausar has called it Secret?Perhaps, he might have thought it would attract attention. But that, at least, is not Gidwani's fault! It is Kausar's in the first place.

10/n The sentence as quoted, or rather misquoted, by Kausar, and repeated by Yazdani, is from Gidwani's novel on page 210. “(The Sword of Tipu Sultan, page 210. Italics mine. Italicized words were omitted by Kausar; Yazdani blindly followed him.)

11/n In the novel this is the last sentence in Tipu Sultan's address to a large assembly of Indian and French officers. It is not an actual address delivered by Tipu; it is an address which Gidwani has made Tipu to deliver in the novel.

12/n Kausar believes that such imaginary quotations will “show different facets of Tipu's philosophy and character!” And, praising Kausar in the foreword to his Secret Correspondence of Tipu Sultan, B. R. Grover, the then Director of Indian Council of Historical Research, says:

13/n “Compiled by an Archivist in his methodical & scientific approach this work is a welcome addition to the source material of the late 18th century history of India. It affords fresh ground for an assessment of the character & activities of Tipu Sultan & his place in history.”

14/n There is more; but I don’t want to keep mentioning them here.

But we must grant Kavesh Yazdani one thing: His is a novel way of Historical research which has now become narrative of most Tipu loving historians.

But we must grant Kavesh Yazdani one thing: His is a novel way of Historical research which has now become narrative of most Tipu loving historians.

15/n Tipu: freedom fighter?

It has been claimed that Tipu was the first freedom fighter,for India's independence from British Rule! Some writers have suggested this in a more subtle manner. Let’s inspect👇🏼

It has been claimed that Tipu was the first freedom fighter,for India's independence from British Rule! Some writers have suggested this in a more subtle manner. Let’s inspect👇🏼

16/n An anthology of essays, edited by Irfan Habib, has been named Confronting Colonialism: Resistance and Modernisation under Haidar Ali and Tipu Sultan, as if it was Tipu who was confronting Colonialism! What could be further from truth?

17/n Tipu fought just to save his kingdom and failed. Why should that make him a martyr in the cause of India's independence? Hitler, too, fought against the British. He did so, not for Germany but because they were a hindrance to his plan of enslaving the Poles & the Russians.

18/n Francois R,captain of a French Ship dismasted in Feb1797 &put in Mangalore was a conman who represented himself as second-in-command at Mauritius,then under French rule,authorized to discuss Mysorean cooperation with a French force already assembled to expel Brit from India.

19/n Tipu fell for it and initiated correspondence with the French authorities. His proposal to the French, dated 2nd April, 1797, inserted in his instructions to his envoys, was👇🏼

20/n ...that the French should send “10,000 [French] soldiers” and “30,000 Blacks” to support Tipu and in return the territory and property which might be captured from the British and the Portuguese were “to be equally divided” between the French and Tipu.

21/n Reference for above:

(The Asiatic Annual Register, for the year 1799, page 195 in the section entitled 'Supplement to the Chronicle'.)

😂So this was Tipu's idea of his so called confrontation with colonialism: replacing the British by the French!

(The Asiatic Annual Register, for the year 1799, page 195 in the section entitled 'Supplement to the Chronicle'.)

😂So this was Tipu's idea of his so called confrontation with colonialism: replacing the British by the French!

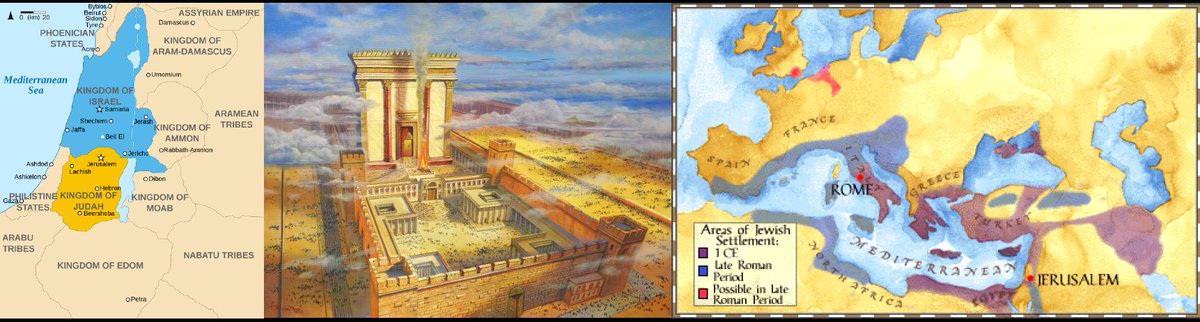

22/n If we refer to his letter to Zaman Shah, the ruler of Afghanistan, dated 5th February, 1797: They were to unite in a jihad against the infidels and free the region of Hindustan from the contamination of the enemies of Islam.

23/n The Shah was to expel the Marathas from Delhi & then the Afghan army from the north & Tipu's from the south were to crush the remaining power of the Marathas in the Deccan.

🤔This was Tipu's so called anti- colonialism: reestablishment of Islamic rule in India.

🤔This was Tipu's so called anti- colonialism: reestablishment of Islamic rule in India.

24/n Tipu carried away from their homeland thousands and thousands of Canarese Christians & Kodavas (Coorgis) and converted them by force;, by his own admission, he had converted lakhs of Nairs to Islam.

25/n Several books written under his patronage exhort his Musalman subjects to wage war against the infidels, that is non-Musalmans, and to persecute the Hindus and extirpate the Christians.

I’ll explain further from 26/n in sometime.

I’ll explain further from 26/n in sometime.

26/n His revenue regulations lay down that every person who should become a convert to Muhammadan faith was to pay only half the tax charged on others and was to be exempt from house tax. He is known to have destroyed a large number of temples.

27/n All this shows, beyond reasonable doubt, that his was an Islamic state. There was nothing anti-colonial in it. Tipu's struggle was against the infidels (non- Musalmans), not against colonials or colonialism.

28/n Let’s now break myth: Tipu, a donor of grants to Hindu institutions?

B. Sheik Ali in his Tipu Sultan: a Crusader for Change, page 3, states: “Tipu gave liberal grants to the temples. Records show as many as 156 temples received grants [from him].”

B. Sheik Ali in his Tipu Sultan: a Crusader for Change, page 3, states: “Tipu gave liberal grants to the temples. Records show as many as 156 temples received grants [from him].”

29/n Interestingly,he has not cited any records to support this statement. But it is evident that it is based on B. N. Pande's Aurangzeb and Tipu Sultan, page 14.

30/n B.N. Pande says there: “Prof. Srikantiah supplied me with the list of 156 temples to which Tipu Sultan used to pay annual gifts.” (His name is also spelt Srikantia and Srikantis on the same page. Let us stick to Srikantiah.

31/n Mr Pande has not reproduced the list,nor has he mentioned the date on which it was sent to him. Sir Brijendra Nath Seal,the then VC of Mysore University, had forwarded Pande's letter to Prof. Srikantiah & he had responded by giving Pande this list and some other information.

32/n Seal was VC of Mysore University from 1921 to 1929. So Pande must have received this list in or before 1929. He first mentioned that list in his lecture on Tipu, delivered on 18th November 1993, that is 64 years after he received it.

33/n That lecture and the one on Aurangzeb, delivered on 17th November, 1993, were delivered

Refutation of Tipu's False Glorification 79

under the auspices of the Institute of Objective Studies in the Academic Staff College, Jamia Milia Islamia, New Delhi.

Refutation of Tipu's False Glorification 79

under the auspices of the Institute of Objective Studies in the Academic Staff College, Jamia Milia Islamia, New Delhi.

34/n These two lectures were printed in the form of a booklet under the name Aurangzeb and Tipu Sultan.

So this is the source of the list of temples-yes, 156 temples-which, we are supposed to believe, as Sheikh Ali believes, received annual gifts from Tipu.

So this is the source of the list of temples-yes, 156 temples-which, we are supposed to believe, as Sheikh Ali believes, received annual gifts from Tipu.

35/n The list was provided by Prof. Srikantiah to Pande in or before 1929 and Pande recalled it 64 years later. Believe it or not. 🤔

Before moving further I would like to give the one more example of his art.

Before moving further I would like to give the one more example of his art.

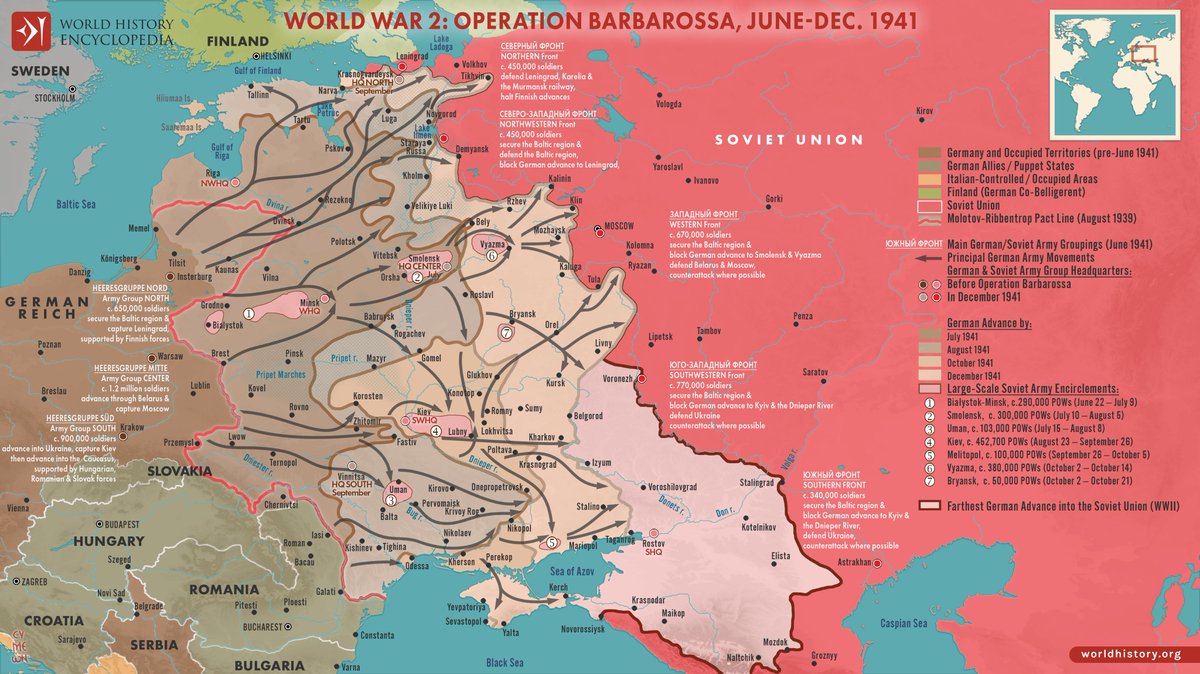

36/n In his paper on Aurangzeb, Pande has told the following story: Once while Aurangzeb was passing near Varanasi on his way to Bengal a halt was made to let the Ranis of the Hindu Rajas in the emperor's retinue have a dip in the Ganges and pay their homage to Lord Vishvanath.

37/n After performing the rituals the Ranis, except the Rani of Kutch, returned. After a search it was found that there was a secret underground chamber just beneath Lord Vishvanath's seat and they found the Rani there, “dishonoured and crying, deprived of all her ornaments.”

38/n The enraged Rajas demanded exemplary action. So Aurangzeb issued orders to raze the temple to the ground and punish the Mahant. (Aurangzeb and Tipu Sultan, page 12).

39/n After enthralling the readers with this moving story, Pande adds: “”Dr. Pattabhi Sitaramayya, in his famous book. 'The Feathers and the Stones' has narrated this fact based on documentary evidence.” So Pande raised the story to the status of fact. 😂

40/n He got the name of Sitaramayya's book wrong: It is actually ‘Feathers and Stones’. 😂

The story told by Pattabhi Sitaramayya in his memoirs, Feathers and Stones, is briefly as follows:

One day Aurangzeb's Hindu noblemen went to see the sacred temple at Benares (Varanasi).

The story told by Pattabhi Sitaramayya in his memoirs, Feathers and Stones, is briefly as follows:

One day Aurangzeb's Hindu noblemen went to see the sacred temple at Benares (Varanasi).

41/n When the party returned it was noticed that the Rani of Kutch was missing.After a search she,bereft of her jewelry,was found in a secret underground chamber. It turned out that it was the doing of the mahants who used to rob the pilgrims in this fashion.

42/n On discovering their wickedness, Aurangzeb ordered the temple to be demolished. But the Rani insisted on a Masjid being built on the ruins of the temple and “to please her, one was subsequently built.” (Feathers and Stones, pages 177-78.). Sitaramayya adds:

43/n “The story Benares Masjid was given in a rare manuscript in Lucknow which was in possession of a Maulana who had read it in the Ms and who though he promised to look it up & gave the Ms to a friend, to whom he had narrated the story, died without fulfilling his promise.”

44/n So this is the stupid story Sitaramayya believed and also wanted others to believe. His expectation came true. Bingo! There was at least one person who believed it: B.N. Pande! Not only did he believe it, he embroidered it further.

45/n In Sitaramayya's story the Rani lost her jewelry only, Pande made her lose her honour as well! I leave it to the readers' judgment whether to believe Pande's story of “the list of 156 temples to which Tipu Sultan used to pay annual gifts.”

46/n As for Sheik Ali, the believer, the less said the better.

B. A. Saletore's article 'Tipu Sultan as Defender of the Hindu Dharma' was first published in (Medieval India Quarterly, Vol. I, No. 1, pages 43-55.) It is reprinted in Confronting Colonialism, pages 115-30.

B. A. Saletore's article 'Tipu Sultan as Defender of the Hindu Dharma' was first published in (Medieval India Quarterly, Vol. I, No. 1, pages 43-55.) It is reprinted in Confronting Colonialism, pages 115-30.

47/n The first document discussed in the article is a Kannada sanad, issued under Tipu's seal, about a dispute regarding worship in a temple at Mysore.

48/n Saletore, who believes that it illustrates “Tipu's role as a legislator in Hindu religious matters,” and “not only remedies the injustice done by his own official, but also rectifies an omission made by a previous Hindu ruler of Mysore”,...contd

49/n ...waxes eloquent in praising Tipu for his knowledge of Hindu religious practices. But, alas, the date of the document shows that it was issued, if ever, after Tipu's death!

50/n Saletore says that “the second line of the sanad contains merely the Hindu cyclic year and the month and the day (Siddhartha saum. Bhadrapada ba. 5) which corresponds to 15 September 1783.” (Confronting Colonialism, page 116.)

51/n But here he is in error. The cyclic year Siddhartha which occurred only once during Tipu's life corresponds with Shaka year 1721. Bhadrapada Badi 5 of the year named Siddhartha, Shaka year 1721 corresponds with 19th September, 1799.

52/n Tipu had died on 4th May, 1799. The Sultan, the inscription on whose sword read, “My victorious sabre is lightening for the destruction of the unbelievers”, would have turned in his grave had he learnt that Saletore was calling him 'Defender of the Hindu Dharma'!

53/n (For inscription see History of Mysore, Vol. III, page 1073.)

S. Subbaray Chetty's article, 'Tipu's Endowments to Hindus and Hindu Institutions' first published in Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, pages 416-19, is reprinted in Confronting Colonialism, pages 111-14

S. Subbaray Chetty's article, 'Tipu's Endowments to Hindus and Hindu Institutions' first published in Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, pages 416-19, is reprinted in Confronting Colonialism, pages 111-14

54/n It is a half-baked piece. At several places he cites Local Records as his source without giving sufficient details.

55/n He sets out to give a list of charities and endowments Tipu made to Hindus and Hindu institutions, but at least one of these is a permission for the construction of a mosque on the “site of a temple got from the Brahmins with their goodwill”.

56/n And two are grants to Dargahs, one at Penukonda and the other near Tonnur. Most of the other records cited are merely memorandums of grants, not the original farmans or their copies. There is no way, therefore, of examining their authenticity.

57/n In most cases dates are lacking, or are not given. Some of the grants are made to astrologers; these cannot be regarded as evidence of Tipu's tolerance or respect for other religions.

58/n Nevertheless it is true, though strange, that Tipu gave grants to some Hindu temples, and employed the Brahmans to perform japa (incantations), penances and other rites, to ensure his victory. Wilks rightly observes:👇🏼

59/n “That Haidar himself, half a Hindu, should sanction these ceremonies is in the ordinary course of human action; but that Tipu, the most bigoted of Mahomedans, professing an open abhorrence and contempt for the Hindu religion,...

60/n and the Brahmans, its teachers, destroying their temples, and polluting their sanctuaries, should never fail to enjoin the performance of the jebbum (japam) when alarmed by imminent danger is, indeed, an extraordinary combination of arrogant bigotry and...

61/n ..trembling superstition; of general intolerance, mingled with occasional respect for the object of persecution.” (Historical Sketches of the South of India, Vol. I, pages 813-14, footnote.)

62/n This superstition of the tyrant became particularly manifest since 1790 as utter destruction stared him in the face.

In April 1791 the freebooters (called Pindaris) who followed in the wake of the Maratha army plundered the Shankaracharya's math at Shringeri.

In April 1791 the freebooters (called Pindaris) who followed in the wake of the Maratha army plundered the Shankaracharya's math at Shringeri.

63/n This was certainly a most reprehensible act. But to place it in its proper context, it must be remembered that such freebooters followed all non-European armies in India.

64/n It was common practice to let them loose to devastate the enemy's territory and thus, by destroying his economy, compel him to sue for peace. It was something like strategic bombing of the Second World War. It brings to mind Sherman's famous dictum “War is hell.”

65/n Such freebooters, called looties by the British, followed Tipu's army also. Even the grain dealers supplying the British army in India indulged in plunder.

66/n But there is a difference: the atrocities against the Hindus and Christians, and their religious institutions, committed by Tipu's soldiers were the result of Tipu's specific orders; the math at Shringeri was plundered by freebooters, no Maratha officer had ordered the act.

67/n In fact the Maratha officers were anguished by it and some efforts were made to restore the plundered goods and appease the Shankaracharya.

68/n Dr. A. K.Shastry,the editor of The Records of the Sringeri Dharmasamsthana,observes: “However Peshwa Madhavrao Narayan(popularly known as Sawai Madhavrao, AD 1774-95)conducted an enquiry & ordered Parasuram Bhau to give compensation & return the looted articles to the Matha.

71/n ref: (The Records of the Sringeri Dharmasamsthana, pages 171-72.)

Tipu, naturally, was quick to capitalize on the event. (So are his modern apologists and admirers!)

Tipu, naturally, was quick to capitalize on the event. (So are his modern apologists and admirers!)

72/n He had already requested the Shankaracharya to offer prayers to Lord Ishwara (Shiva) for the defeat of the enemies. (The Records of the Sringeri Dharmasamsthana, Letter Nos. 86-87, 3rd April and 20th June 1791.)

73/n When he came to know that the math was plundered by the Maratha cavalry (in fact, by the Pindaris) he made a grant of money for the restoration of the temple and reinstallation of the idol.

74/n He did not forget to request the Shankaracharya to perform penance for the destruction of the enemies and prosperity of the government. (The Records of the Sringeri Dharmasamsthana, Letter No. 88, 6th July, 1791.)

75/n This was the same Tipu who had carried away from Canara thousands of Christians and forcibly converted to Islam, who had carried away from Coorg thousands of Hindus and forcibly converted them to Islam, who had forcibly converted lakhs of Hindus in Malabar.

76/n He is the same Tipu who had commissioned several books which exhorted his subject Musalmans to wage jihad against the non- Musalmans, who had desecrated and destroyed several Hindu temples and Christian churches, and who had forced many Hindu women into his harem.

77/n This bigoted tyrant was lamenting because the Shankaracharya's math was looted by some freebooters! Could there be a better example of the proverbial crocodile tears?

78/n Such is the brief history of Tyrant Tipu who never fought for India nor donated to temples holistically. I will also bust the myth of ‘Tipu the Misslile Man’ some other time. Till then you can care to respond to above thread where I have busted the myth of’Tiger Tipu Sultan’

N/n In above thread of 78 tweets I have busted the myth as claimed by @tufailelif . Refer SC👇🏼. Request to help me reach this rebuttal to him since he has already blocked me. Cc @ShefVaidya @KanchanGupta @RatanSharda55 @GitaSKapoor @_NAN_DINI

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh