1/7 When we started thinking about how to model personal wealth in an economy of interacting people, we soon wrote down an equation we called Re-allocating Geometric Brownian Motion (RGBM). We felt logically forced to use this as a starting point.

dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2…

dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2…

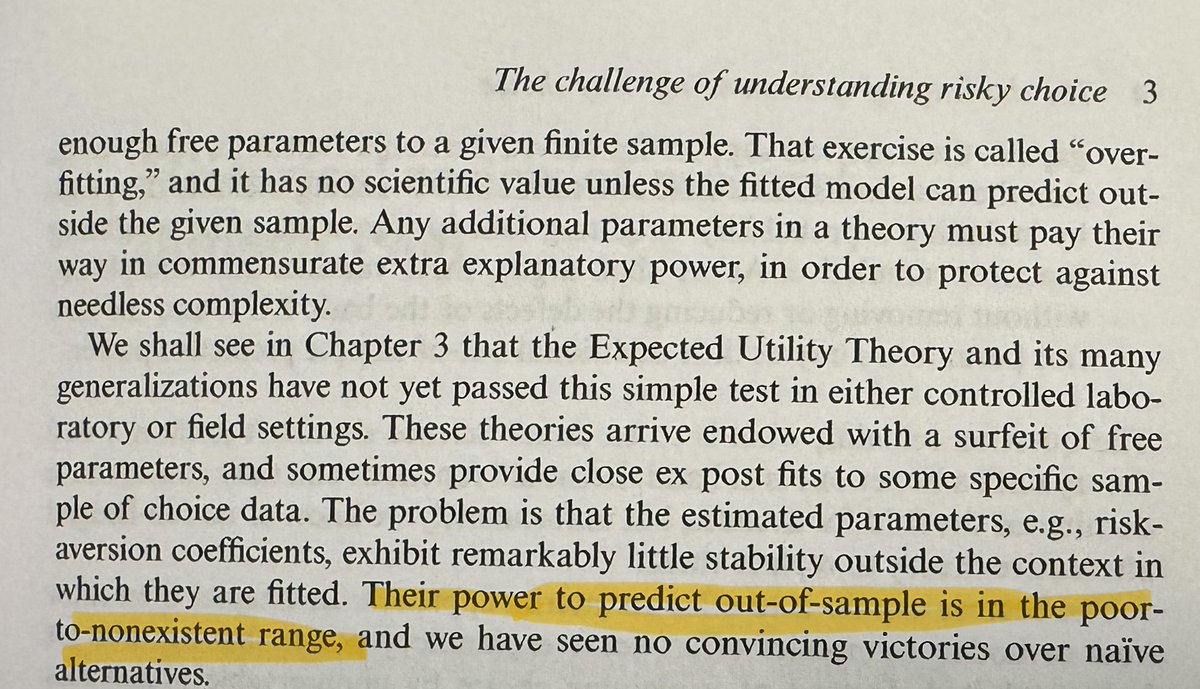

2/7 But the economics papers we saw on the topic all used much more complicated, intractable, and from what we could tell quite arbitrary models, i.e. equations trying to represent the same thing we were trying to model.

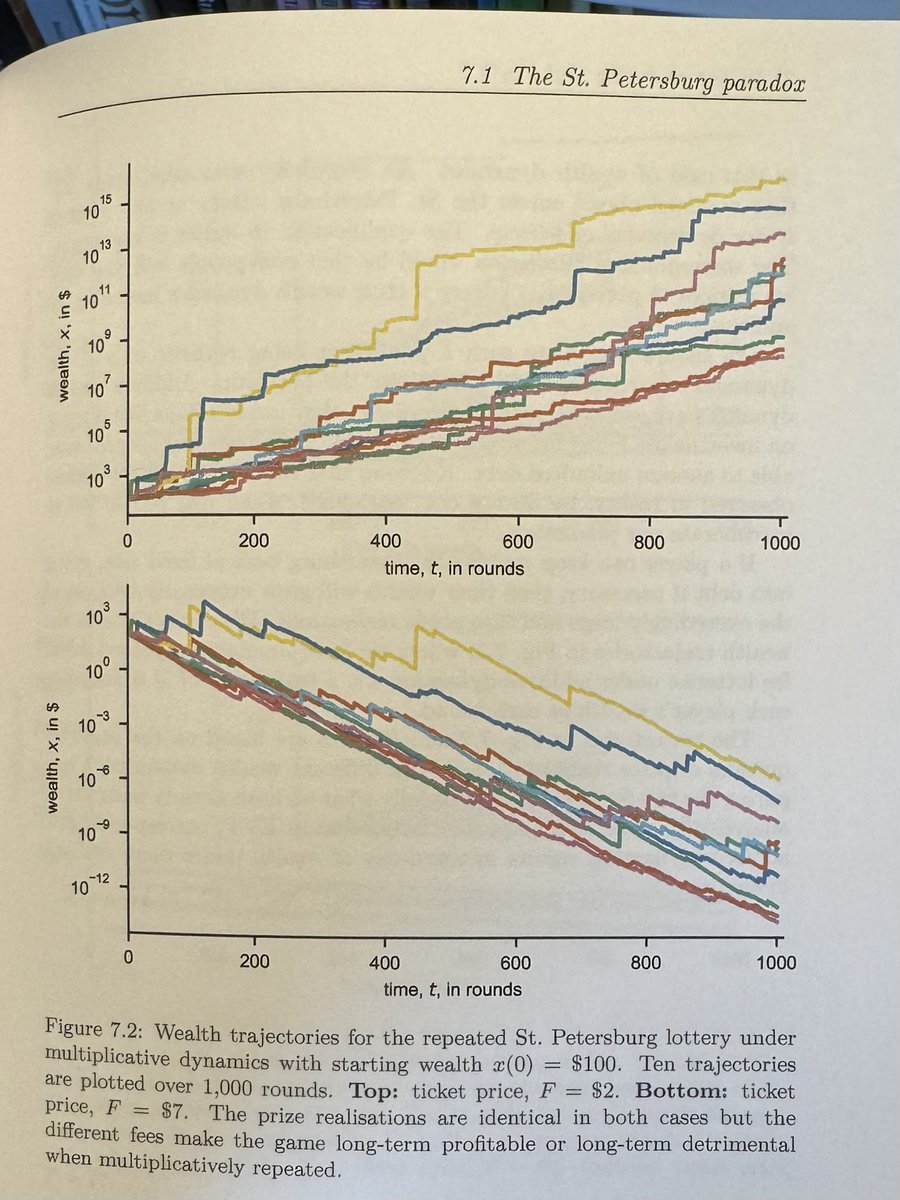

3/7 Undeterred, we went ahead with our analysis, with somewhat shocking results. It showed an unstable wealth distribution. Where you sit in the distribution is hugely non-ergodic, time scales are much longer than people thought, or non-existent.

ergodicityeconomics.com/2017/08/14/wea…

ergodicityeconomics.com/2017/08/14/wea…

4/7 Very serious consequences for questions in welfare economics, financial markets, interest rates and on and on.

No economics journal wanted to publish it.

No economics journal wanted to publish it.

5/7 Then we noticed Bouchaud and Mezard had studied the same equation in 2000: they'd also felt there wasn't much choice in how to model this, and they'd come to similar conclusions. We picked up some great techniques from them.

lptms.u-psud.fr/membres/mezard…

lptms.u-psud.fr/membres/mezard…

6/7 Later, we saw, Liu and Serota also arrived at this equation, in 2017.

isiarticles.com/bundles/Articl…

And just the other day, we learned that Marsili, Maslov, and Zhang were studying it for the same reasons, in 1998.

arxiv.org/abs/cond-mat/9…

isiarticles.com/bundles/Articl…

And just the other day, we learned that Marsili, Maslov, and Zhang were studying it for the same reasons, in 1998.

arxiv.org/abs/cond-mat/9…

7/7 What does this mean?

4 teams of physicists independently, over 20 years, all arrived at the same equation to model a key economics problem, with alarming results.

I know of no study of this equation published in an economics journal -- do you?

4 teams of physicists independently, over 20 years, all arrived at the same equation to model a key economics problem, with alarming results.

I know of no study of this equation published in an economics journal -- do you?

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh